Eileen Joyce: Difference between revisions

Removing from Category:Australian classical pianists has subcat using Cat-a-lot |

Mitch Ames (talk | contribs) Remove supercategory of existing diffusing subcategory per WP:CATSPECIFIC, WP:CAT#Articles |

||

| Line 184: | Line 184: | ||

[[Category:20th-century Australian musicians]] |

[[Category:20th-century Australian musicians]] |

||

[[Category:People from Zeehan]] |

[[Category:People from Zeehan]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century Australian women]] |

|||

[[Category:20th-century Australian women pianists]] |

[[Category:20th-century Australian women pianists]] |

||

Latest revision as of 01:34, 15 December 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

Eileen Joyce | |

|---|---|

Eileen Joyce in 1952 | |

| Born | Eileen Alannah Joyce 21 November 1907 or 1 January 1908 |

| Died | 25 March 1991 (aged 83) Redhill, Surrey, England |

| Musical career | |

| Instrument(s) | Piano, harpsichord |

Eileen Alannah Joyce CMG (died 25 March 1991) was an Australian pianist whose career spanned more than 30 years. She lived in England in her adult years.

Her recordings made her popular in the 1930s and 1940s, particularly during World War II. At her zenith she was compared in popular esteem with Gracie Fields and Vera Lynn.[1] When she played in Berlin in 1947 with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, an eminent German critic classed her with Clara Schumann, Sophie Menter and Teresa Carreño.[2] When she performed in the United States in 1950, Irving Kolodin called her "the world's greatest unknown pianist".[3]

She became even better known during the 1950s, when she played 50 recitals a year in London alone, which were always sold out. She also performed a series of "Marathon Concerts", playing as many as four concertos in a single evening. Her Mozart was described as "of impeccable taste and feeling", she was a Bach player "of commanding authority", and "a Lisztian of both poetry and bravura".[3] Her playing of the second movement of Rachmaninoff's 2nd Piano Concerto in the films Brief Encounter and The Seventh Veil (both 1945) helped popularise the work. A 1950 biography of Joyce's early life became a best-seller and was translated into various languages.[2] A feature film, Wherever She Goes (1951), was based on the book, but was much less successful.

Despite her fame, her name slipped from public sight after her retirement in the early 1960s. Her recordings have resurfaced on CD.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Eileen Joyce was born in Zeehan, a mining town in Tasmania. She was born in Zeehan District Hospital and not, as many reference works claim, in a tent.[4] She frequently claimed her birthday was 21 November in either 1910 or 1912,[5] but a search of Tasmanian birth registrations shows she was born on 1 January 1908.[4][a] She was the fourth of seven children of Joseph Thomas Joyce (born 1875), grandson of an Irish immigrant, and Alice Gertrude May.[6] One of her three elder sisters (all born in Zeehan) died shortly after birth, and one of her three younger brothers died at age two.[7]

The family had moved to Western Australia by 1911. They lived firstly in Kununoppin and later in Boulder.[4] Despite their poverty, her parents encouraged her musical development and she began music lessons at age 10.[7]

She attended St Joseph's Convent School in Boulder where she was taught music by Sister Mary Monica Butler. When she was aged 13, her family's financial circumstances meant that Eileen had to leave school. However, they managed to find enough money to pay for piano lessons with a private teacher, Rosetta Spriggs (a great-grandpupil of Antonín Dvořák). She made Eileen known to a visiting Trinity College examiner, Charles Schilsky, a former violinist with the Lamoureux Orchestra in Paris. Schilsky was extremely impressed with Joyce: he later wrote "There is no word to explain Miss Joyce's playing other than genius. She is the biggest genius I have ever met throughout my travels".

He approached the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Perth and arranged for Eileen to be sent to Loreto Convent in Claremont, Perth, to continue her schooling. Her music teacher there was Sister John More. Joyce entered the 1925 and 1926 Perth Eisteddfods, winning the Grand Championship in 1926. Schilsky continued to make her name known, and wrote a letter to Perth newspapers urging her to be sent to Paris to study.

In May 1926, the Premier of Western Australia, Philip Collier, set up an "Eileen Joyce Fund" with the aim of collecting £1,000 to help Joyce's future career. In August 1926, Percy Grainger, on a concert tour, was introduced to Joyce by Sister John More. He heard her play, and then wrote an open letter to the people of Perth:[8]

I have heard Eileen Joyce play and have no hesitation in saying that she is in every way the most transcendentally gifted young piano student I have heard in the last twenty-five years. Her playing has that melt of tone, that elasticity of expression that is, I find, typical of young Australian talents, and is so rare elsewhere [...].

He suggested she would have the same celebrity as Teresa Carreño and Guiomar Novaes.[4]

Grainger recommended she study with an Australian master so that her playing would not become "Europeanised" or "Continentalised", and in his view Ernest Hutcheson, then teaching in New York, was the best choice.[4] A short time after Grainger left, Wilhelm Backhaus arrived for a tour of Western Australia. He also heard her and suggested the Leipzig Conservatorium, then regarded as the mecca of piano teaching, would be more suitable (Hutcheson himself had studied there).[4]

From 1927 to 1929, she studied at the Leipzig Conservatorium, firstly with Max von Pauer and later with Robert Teichmüller. There, she learnt unusual repertoire such as Max Reger's Piano Concerto and Richard Strauss's Burleske in D minor. She then went to the Royal College of Music in London where, with assistance from Myra Hess, she studied under Tobias Matthay. She also had lessons with Adelina de Lara for a short period in 1931.[7]

Career

[edit]On 6 September 1930, she made her professional debut in London at a Henry Wood Promenade Concert, playing Prokofiev's Piano Concerto No. 3. Her first solo recital in England was on 23 March 1931.[9] In 1932, she attended Artur Schnabel's masterclasses in Berlin for two weeks.[7] In 1933, she made the first of her many recordings. The session produced Franz Liszt's Transcendental Étude in F minor and Paul de Schlözer's Étude in A-flat, Op. 1, No. 2.[7][10]

In 1934, for the Proms' 40th season, Joyce played Busoni's Indian Fantasy.[6] She became one of the BBC's most regular broadcasting artists, as well as being in demand for concert tours in the provinces. In 1935, she was a supporting artist for Richard Tauber.

Joyce was the first pianist to play Shostakovich's piano concertos in Britain – the First on 4 January 1936, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sir Henry Wood. She also played the Second on 5 September 1958, with the same orchestra, under Sir Malcolm Sargent, at the Royal Albert Hall.[7]

In 1938, Eric Fenby said he was thinking of writing a concerto for her, but that did not happen.[7] On 18 July 1940, the London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) presented a "Musical Manifesto" concert to raise funds, after its founder, Sir Thomas Beecham, said he could no longer afford to fund it. The author J. B. Priestley, a longtime supporter of the orchestra, made a speech, which was widely publicised and which helped attract public support. Three conductors – Sir Adrian Boult, Basil Cameron and Malcolm Sargent – took part, and Joyce played Grieg's Piano Concerto in A minor, under Cameron's direction.[11] During the war she performed regularly with Sargent and the LPO, especially in blitzed areas. She was a frequent performer in Jack Hylton's "Blitz Tours" during the war,[12] and she appeared regularly at the National Gallery concerts organised by Dame Myra Hess.[13]

Although small in stature, Joyce was strikingly beautiful, with chestnut hair and green eyes. She changed her evening gowns to suit the music she was playing: blue for Beethoven,[12] red for Tchaikovsky,[8] lilac for Liszt, black for Bach, green for Chopin, sequins for Debussy, and red and gold for Schumann.[2][14] She also arranged her hair differently depending on the composer – up for Beethoven, falling free for Grieg and Debussy,[14] and drawn back for Mozart.[8] Until 1940, she designed her own gowns, but in August she volunteered as a firewatcher, which revived her chronic rheumatism so, on the LPO tours, she had to wear a plaster cast encasing her shoulder and back. She bought gowns specially designed by Norman Hartnell to cover the cast, and she often wore Hartnell thereafter.[7] Richard Bonynge was a music student in Sydney during her 1948 tour, and said: "She brought such glamour to the concert stage. We all used to flock to her concerts, not least because of the extraordinary amount of cleavage she used to show!".[8]

She had numerous recital programs and over 70 concertos in her repertoire, including such unusual works as the Piano Concerto in E-flat major by John Ireland and Rimsky-Korsakov's Piano Concerto in C-sharp minor. In 1940, she made the first recording of the Ireland concerto, with the Hallé Orchestra under Leslie Heward,[7] and was chosen to play it at a 1949 Proms concert with the LPO under Sir Adrian Boult, celebrating Ireland's 70th birthday.[6] The performance was recorded and released commercially.[7]

However, there were three concertos that Joyce played more than any others, and were her firm favourites: the Grieg Piano Concerto in A minor, the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1, and most of all, the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2. She never played any other Rachmaninoff concertos.

She appeared with all the principal UK orchestras as well as many overseas orchestras. She toured Australia in 1936, during which she was the soloist at the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra's first Celebrity Concert, conducted by William Cade.[15] She toured in 1948, and performed the Grieg concerto at the gala opening concert of the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra, under Joseph Post.[7][16] In June 1947, she appeared at Harringay Arena in the Harringay Music Festival with Sir Malcolm Sargent.[17]

She had planned to tour the United States in 1940 and 1948, but both tours were cancelled, the first one on account of the war. She finally appeared in Philadelphia] and Carnegie Hall, New York, in 1950, with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy. She had earlier appeared with them in Britain in 1948, on the orchestra's first major overseas tour. While her Philadelphia concerts attracted excellent reviews, the New York critics were much less impressed. This was possibly due to the conservative repertoire she chose on Ormandy's strong advice (Beethoven's "Emperor" Concerto and Prokofiev's 3rd), rather than the works she would prefer to have played (the Grieg concerto, Rachmaninoff's 2nd and Tchaikovsky's 1st). She was never particularly popular or even well known in the United States, and she never returned.

Her other tours abroad were to New Zealand in 1936 and 1958, France in 1947, the Netherlands in 1947 and 1951, and Germany in 1947, where she played for Allied troops. She was the first British artist for more than a decade to give concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.[2] She toured Germany again in 1949 and 1958, Italy in 1948, Belgium in 1950 and 1952, South Africa in 1950, and Norway in 1950. She had planned to tour Sweden on that trip, but fell down a flight of stairs after performing the Grieg concerto in Oslo, and the remainder of her trip was cancelled. She did, however, visit Sweden in 1951 and 1954, Yugoslavia in 1951, visiting Belgrade, Zagreb, and Ljubljana, Brazil and Argentina in 1952, Finland in 1952, Spain and Portugal in 1954, the Soviet Union in 1956 and 1958, Denmark and other Scandinavian countries in 1958, and India and Hong Kong in 1960.

In November 1948, Joyce broke the previous record of 17 appearances at London's Royal Albert Hall in a single calendar year.[2] She had often performed two concertos in a single concert and, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, she gave a series of "Marathon Concerts", in which she played up to four concertos in a single evening. For example, on 10 December 1948, in Birmingham, she played César Franck's Symphonic Variations, Manuel de Falla's Nights in the Gardens of Spain, Dohnányi's Variations on a Nursery Tune and Grieg's Piano Concerto in A minor. On 6 May 1951 at the Royal Albert Hall she performed Haydn's D minor Harpsichord Concerto, Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1, John Ireland's Concerto in E-flat major, and Grieg's concerto, with the Philharmonia Orchestra, under conductor Milan Horvat.[7] On another occasion, she played Chopin's Piano Concerto No. 1, Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2, John Ireland's concerto and Beethoven's "Emperor" Concerto.[6]

She expressed a new-found interest in the harpsichord, receiving lessons from Thomas Goff and, in 1950, she gave the first of a number of harpsichord recitals. In the 1950s, she also gave a series of concerts featuring four harpsichords, her colleagues including players such as George Malcolm, Thurston Dart, Denis Vaughan, Simon Preston, Raymond Leppard, Geoffrey Parsons and Valda Aveling.[7]

In 1956, Joyce was Gerard Hoffnung's first choice as soloist in Franz Reizenstein's parodic Concerto Popolare, to be played at the inaugural Hoffnung Music Festival, but she declined, and the job went to Yvonne Arnaud. She appeared as soloist at Sir Colin Davis's debut as a conductor, with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO), on 22 September 1957, playing Tchaikovsky's Concerto No. 1.[7] On 28 November 1957, she participated in the premiere performance of Malcolm Arnold's Toy Symphony, Op. 62, at a fund-raising dinner for the Musicians Benevolent Fund. The work has parts for 12 toy instruments, which were taken by Joyce, Eric Coates, Thomas Armstrong, Astra Desmond, Gerard Hoffnung, Joseph Cooper, and other prominent people, all conducted by the composer.[11][18]

In 1960, during her tour of India, her Delhi recital was attended by the Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. During that tour, which also included Hong Kong, she announced she was retiring, and her final recital was at a festival in Stirling, Scotland, on 18 May 1960, where she played two sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti, Beethoven's Appassionata sonata, and works by Mendelssohn, Debussy, Chopin, Ravel, Granados and Liszt. She did, however, return to the concert platform a handful of times over the next 21 years, the first not until 1967, when she played Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2 with the RPO conducted by Anatole Fistoulari, at the Royal Albert Hall.[6] That was the work that had made her famous in the film Brief Encounter in 1945, and it was to be her last concerto performance. Also in 1967, she appeared with three other harpsichordists and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields under Neville Marriner.

In 1967, she started to foster the career of the ten-year-old Terence Judd. In 1969, she appeared alongside fellow Australian pianist Geoffrey Parsons in a two-piano recital at Australia House, London. In 1979, she gave a two-piano recital with Philip Fowke. She appeared again with Geoffrey Parsons on 29 November 1981 at a fund-raising concert at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.[9] That proved to be her very last appearance as a pianist because another performance, scheduled in 1988, had to be cancelled).[19]

In August 1981, Eileen Joyce served on the jury of the 2nd Sydney International Piano Competition of Australia (SIPCA), alongside Rex Hobcroft, Cécile Ousset, Abbey Simon, Claude Frank, Gordon Watson, Roger Woodward and others. In 1985, she conducted preliminary auditions in London for the 3rd SIPCA, and attended the competition in Sydney as Music Patron and deputy chairman of the jury. She gave Rex Hobcroft an anonymous donation of $20,000 for the competition.[7] She was also Music Patron for the 4th SIPCA in 1988.[20]

On 21 March 1991 she fell in her bathroom, fracturing her hip. She was taken to East Surrey Hospital, where she died on 25 March. On 8 April, she was cremated and her ashes were interred at St Peter's Anglican Church, Limpsfield, next to Sir Thomas Beecham.[4] On 7 June, a memorial service was conducted at St Peter's Church.[7]

Conductors

[edit]The list of conductors with whom Joyce worked includes: Ernest Ansermet, Sir John Barbirolli, Sir Thomas Beecham, Eduard van Beinum, Sir Adrian Boult, Warwick Braithwaite, Basil Cameron, Sergiu Celibidache, Albert Coates, Sir Colin Davis, Norman Del Mar, Anatole Fistoulari, Grzegorz Fitelberg, Sir Alexander Gibson, Sir Dan Godfrey, Sir Hamilton Harty, Sir Bernard Heinze, Milan Horvat, Enrique Jordá, Herbert von Karajan, Erich Kleiber, Henry Krips, Constant Lambert, Erich Leinsdorf, Igor Markevitch, Sir Neville Marriner, Jean Martinon, Charles Münch, Eugene Ormandy, Joseph Post, Clarence Raybould, Victor de Sabata, Sir Malcolm Sargent, Carlos Surinach, and Sir Henry J. Wood.

In a 1969 interview she said the greatest conductor she had ever worked with was Sergiu Celibidache.[7] She said "he was the only one who got inside my soul". In the late 1940s and 1950s, she and her partner Christopher Mann worked tirelessly to get Celibidache good engagements in Britain.

Films

[edit]With her partner Christopher Mann's influence, Joyce contributed to the soundtracks of a number of films. She is best known as the soloist in Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2, used to great effect in David Lean's film Brief Encounter (1945).

She also provided the playing for the piano music in the 1945 film The Seventh Veil, but this was uncredited in the film. This music again included the Rachmaninoff 2nd Concerto, and also Grieg's Concerto in A minor; as well as solo pieces by Mozart, Chopin and Beethoven (the slow movement of the Pathétique Sonata assumed a particular importance in the film).

She appeared in Battle for Music,[21] a 1945 docu-drama about the struggles of the London Philharmonic Orchestra during the war, in which a number of prominent composers and performers appeared as themselves.[7]

Arthur Bliss's music for the 1946 film Men of Two Worlds[22] (released in the US as Kisenga, Man of Africa, and re-released as Witch Doctor) includes a section for piano, male voices and orchestra, titled "Baraza", which Bliss said was "a conversation between an African Chief and his head men". Joyce played this for the film, with Muir Mathieson conducting. Bliss also wrote this out as a stand-alone concert piece, which Joyce both premiered in 1945 and recorded in 1946. This recording was more favourably received than the film was.[23][24]

She was in the 1946 British film A Girl in a Million,[25] in which she plays a part of Franck's Symphonic Variations. In 1947, her playing of Schubert's Impromptu in E-flat is heard in the segment "The Alien Corn" in the Dirk Bogarde film Quartet.[7] She was also seen as herself in Trent's Last Case (1952), playing Mozart's C minor Concerto, K. 491 at the Royal Opera House with an orchestra under Anthony Collins.[7]

Prelude: The Early Life of Eileen Joyce by Lady Clare Hoskyns-Abrahall was a best-selling 1950 biography that was translated into several languages as well as Braille. While it told the main elements of her story, it was heavily fictionalised in places. The book was dramatised for radio in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, South Africa, Norway and Sweden.[2] Wherever She Goes was a 1951 black-and-white feature film based on the book, directed by Michael Gordon. Released in Australia under the title, Prelude, 1950, it was shot on location in Australia and in a studio in Sydney. Joyce's character was played by Suzanne Parrett, the only film she ever made<,[26]) and Parrett's performance double was Pamela Page. Joyce briefly appeared as herself at the start and end of the film, playing the Grieg concerto. The film was much less successful than the book on which it was based, although it was one of the very few Australian films made before 1970 to be given a (limited) release in New York.[27]

Tim Drysdale, son of artist Sir Russell 'Tas' Drysdale, played the role of Joyce's brother in the movie when he was age 11.[28]

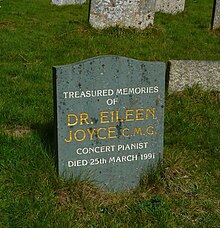

Honours

[edit]In 1971, Joyce was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Music by the University of Cambridge. She was extremely proud of that and insisted on being referred to as "Doctor Joyce".[4] She was awarded similar honours by the University of Western Australia in 1979 and the University of Melbourne in 1982. Her memorial headstone refers to her as "Dr. Eileen Joyce".

In 1981, she was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in the Queen's Birthday Honours, for services to music.[29] While happy to accept the award, she made no secret of her disappointment that she was not made a dame.[4]

On 10 February 1989, a special Australian Broadcasting Corporation tribute concert to her was presented at Sydney Town Hall. Stuart Challender conducted the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, with Bernadette Harvey-Balkus playing the first movement of the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2. Although now frail, Joyce flew to Australia to attend the concert, where she addressed the audience. The playwright Nick Enright interviewed her for the radio broadcast.[7]

Her portrait was painted by Augustus John, John Bratby, Rajmund Kanelba and others. A bronze bust by Anna Mahler stands at the Eileen Joyce Studio at the University of Western Australia in Perth. She was also the subject of photographic portraits by Cecil Beaton, Angus McBean and Antony Armstrong-Jones.[4]

The UWA Conservatorium of Music at the University of Western Australia, in Perth, named the main keyboard studio, which houses a collection of historical and notable keyboard instruments, the Eileen Joyce Studio.

Legacy

[edit]In the days of her greatest fame, the critical climate was still stuffy, and her mass appeal and her succession of different-coloured glamorous gowns, some designed by Norman Hartnell, provoked snobbish reaction and led to her being musically under-rated. Her surviving recordings show that such patronising judgements were very misplaced. She was a fine musician and technically very proficient. For example, her 1941 recording of the Étude in A-flat, Op. 1, No. 2 by Paul de Schlözer is considered unsurpassed. That brief, three-minute work is so demanding that few pianists even attempt it. Sergei Rachmaninoff was said to play it every morning as a warm-up exercise.[30]

Modern virtuoso pianists such as Stephen Hough have expressed amazement that Joyce is not more highly rated among great 20th century pianists than she is. In the foreword to Richard Davis's biography Eileen Joyce: A Portrait, Hough writes: "she displayed all the dazzle and scintillating virtuosity of many great players of the past ... she has to be added to the list of great pianists from the past".

In Zeehan, Tasmania, there is a small park called the Eileen Joyce Reserve. The University of Western Australia maintains a collection of her documents and some personal effects, as well as a collection of antique instruments in a facility named after her. The house where she grew up at 113 Wittenoom Terrace, Boulder, has a commemorative plaque.

In 2011, Appian Publications & Recordings issued a 5-CD box set, Complete Parlophone & Columbia Solo Recordings, 1933–45.[31] In 2017, Decca Eloquence released a 10-CD box set, The Complete Studio Recordings.[32] This release coincided with the publication of Destiny: The Extraordinary Career of Pianist Eileen Joyce, an examination of Joyce's career in concerts, films and recordings, by David Tunley, Victoria Rogers and Cyrus Meher-Homji.[33][34]

Personal life

[edit]On 16 September 1937, Joyce married Douglas Legh Barratt, a stockbroker. Their son, John Barratt, was born on 4 September 1939, the day after the start of World War II. The marriage failed and they separated.[1] Douglas Barratt served with the British Navy, and was killed on active service off Norway on 24 June 1942[35] when his ship HMS Gossamer was bombed and sunk. For reasons she never explained, Joyce always maintained he had died off North Africa but, in 1983, she corrected the record.

Her second partner was Mayfair Film executive Christopher Mann. They lived together from late 1942 until his death in 1978. Mann had previously been married to the Norwegian actress Greta Gynt, and had been Madeleine Carroll's publicist and manager.[7] Mann proved an unsympathetic stepfather to Joyce's son, John, and Joyce herself, between punishing touring schedules and bouts of ill-health, also found little time for him.[9] From the early age of three years and three months, John was sent to boarding school. Joyce's guilt over her neglect of her son, combined with overwork, contributed to a breakdown in 1953.[6] John himself was estranged from his mother from an early age, and he was left nothing in her will, the bulk of her estate going to her grandson, John's son Alexander.[4]

In 1957, Joyce and Christopher Mann bought Chartwell Farm (not the Chartwell historic home) and Bardogs Farm, Kent, from Sir Winston Churchill. Their home in London was bought by the actor Richard Todd.[7]

Joyce and Christopher Mann had always claimed they were legally married, but that did not occur until 1978, after he had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. The wedding took place at Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, with Joyce using the name Eileen Barratt.[36] Mann died at Chartwell on 11 December 1978, aged 75.[4]

Joyce experienced considerable ill health throughout her adult years, particularly severe rheumatism in her shoulders, which at one time necessitated the wearing of a plaster cast, and she also suffered from sciatica. Towards the end of her life, she developed senile dementia.[4] She died in 1991, aged 83, at East Surrey Hospital, Redhill, Surrey.[37]

Notes

[edit]- ^ It was common practice for birth dates to be registered as 1 January when the birth does not occur in a hospital and thus not registered on the exact date, but rather later, which means if 21 November was indeed her date of birth, she was likely born in 1907.

General references

[edit]- Davis, Richard (2001). Eileen Joyce: A Portrait. Foreword by Stephen Hough. Fremantle Arts Centre Press.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Fred Blanks, review of Richard Davis Eileen Joyce: A Portrait, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13–15 April 2001

- ^ a b c d e f Peggy Chambers Profile, Women and the World Today]. Accessed 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b Jeremy Siepmann, The Piano. Accessed 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Davis (2001)

- ^ Her enrolment papers at the Leipzig Conservatory in 1927 stated her birth date was 21 November 1910. In July 1933, for a feature article in Musical Opinion, she gave her birth date as 21 November 1912. On 21 November 1987, some admirers arranged a "75th birthday" celebration for her at White Hart Lodge, which she attended, but did not let on that she was, in fact, 79 or 80. Eileen Joyce (1908–1991) Timeline Archived 18 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Bach Cantatas website

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w "Eileen Joyce (1908–1991) Timeline" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d Live Performance Australia Hall of Fame

- ^ a b c Victoria Laurie, "Forgotten keys", The Weekend Australian, 7–8 April 2001

- ^ Joyce plays Paul de Schlözer's Étude in A-flat on YouTube

- ^ a b Paul R. W. Jackson, The Life and Music of Sir Malcolm Arnold

- ^ a b CD Historicals

- ^ Pianists appearing in Bedford in the 1940s, colindaylinks.com. Accessed 1 December 2022.

- ^ a b Profile, Time Magazine. Accessed 1 December 2022.

- ^ ASO/SASO Archived 19 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "TSO". Archived from the original on 2 January 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- ^ Eileen Joyce – A Timeline, 1908 TO 1991, The Callaway Centre, University of Western Australia.

- ^ Chester Novello

- ^ She had planned to play the third piano part in Percy Grainger's The Warriors at a special concert for Australia's Bicentenary on Australia Day 1988, at the Theatre Royal, London but, after practising, she had to withdraw due to her stiffened fingers.

- ^ SIPCA 2003 newsletter Archived 30 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Battle for Music at IMDb

- ^ Men of Two Worlds at IMDb

- ^ Jeffrey Richards, Imperialism and Music

- ^ John Sugden, Sir Arthur Bliss

- ^ A Girl in a Million at IMDb

- ^ Suzanne Parrett at IMDb

- ^ The New York Times critique

- ^ "Himalaya's Last Visit Before Cruises". West Australian. 31 March 1951.

- ^ It's an Honour: CMG

- ^ "Jorge Bolet - Encores". ArkivMusic. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ Review: Eileen Joyce: Complete Parlophone & Columbia Solo Recordings, 1933–45 by Jeremy Nicholas, Gramophone, (undated)

- ^ "Landmark release: Eileen Joyce – The Complete Studio Recordings", Pianist Magazine, 18 December 2017

- ^ David Tunley; Victoria Rogers; Cyrus Meher-Homji (2017). Destiny: The Extraordinary Career of Pianist Eileen Joyce. Melbourne: Lyrebird Press. ISBN 9780734037879.

- ^ Rosalind Appleby (7 April 2018). "A dazzling ease with the ivories". The Australian.

- ^ HMS Gossamer – Crew

- ^ Aylesbury Registration District, Apr–May–Jun Quarter, Volume 19, Page 0911

- ^ Registration District Surrey South Eastern, Jan–Feb–Mar Quarter, Volume 17, Page 1259, Registration No 391.

External links

[edit]- Eileen Joyce at IMDb

- Eileen Joyce interviewed by John Amis on YouTube

- Tunley, David. "Joyce, Eileen Alannah (1908–1991)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943.

- Biography, bach-cantatas.com

- Eileen Joyce at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- 1900s births

- 1991 deaths

- Australian women classical pianists

- Australian people of Irish descent

- University of Music and Theatre Leipzig alumni

- Alumni of the Royal College of Music

- Australian expatriates in England

- Australian harpsichordists

- Musicians from Tasmania

- Pupils of Tobias Matthay

- Australian Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George

- 20th-century Australian classical pianists

- 20th-century Australian musicians

- People from Zeehan

- 20th-century Australian women pianists