Odia people: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

==Communities== |

==Communities== |

||

[[File:Utkala Khandayat.jpg|thumb|'''Utkala Khandayat''']] |

|||

The Odia people are subdivided into several communities such as the [[Utkala Brahmin|Brahmin]], [[Karan (caste)|Karan]], [[Kayastha]], [[Khandayat]], [[Gopal (caste)|Gopal]], [[Komati (caste)|Kumuti]], [[Chasa caste|Chasa]], [[Bania (caste)|Bania]], [[Kansabanik|Kansari]], [[Gudia (caste)|Gudia]], [[Patra (caste)|Patara]], [[Tanti]], [[Teli]], [[Viswakarma (caste)|Badhei]], [[Kamar (caste)|Kamara]], [[Barika (caste)|Barika]], [[Mali (caste)|Mali]], [[Kumhar|Kumbhar]], [[Siyal (caste)|Siyal]],<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IvJ5G17FkOoC&dq=founder+of+sialkot&pg=PA180 |title=Indian Antiquary: A Journal of Oriental Research in Archaeology, History, Literature, Languages, Folklore Etc |date=1884 |publisher=Education Society's Press |language=en}}</ref> [[Sundhi]], [[Jalia Kaibarta|Keuta]], [[Dhobi|Dhoba]], [[Bhoi|Bauri]], [[Kandara]], [[Domba]], [[Pano (caste)|Pano]],[[Hadi]].<ref name="BehuraMohanty2005">{{cite book|author1=Nab Kishore Behura|author2=Ramesh P. Mohanty|title=Family Welfare in India: A Cross-cultural Study|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=o6Gz0ZDw7PQC&pg=PA49|year=2005|publisher=Discovery Publishing House|isbn=978-81-7141-920-3|pages=49–}}</ref> |

The Odia people are subdivided into several communities such as the [[Utkala Brahmin|Brahmin]], [[Karan (caste)|Karan]], [[Kayastha]], [[Khandayat]], [[Gopal (caste)|Gopal]], [[Komati (caste)|Kumuti]], [[Chasa caste|Chasa]], [[Bania (caste)|Bania]], [[Kansabanik|Kansari]], [[Gudia (caste)|Gudia]], [[Patra (caste)|Patara]], [[Tanti]], [[Teli]], [[Viswakarma (caste)|Badhei]], [[Kamar (caste)|Kamara]], [[Barika (caste)|Barika]], [[Mali (caste)|Mali]], [[Kumhar|Kumbhar]], [[Siyal (caste)|Siyal]],<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IvJ5G17FkOoC&dq=founder+of+sialkot&pg=PA180 |title=Indian Antiquary: A Journal of Oriental Research in Archaeology, History, Literature, Languages, Folklore Etc |date=1884 |publisher=Education Society's Press |language=en}}</ref> [[Sundhi]], [[Jalia Kaibarta|Keuta]], [[Dhobi|Dhoba]], [[Bhoi|Bauri]], [[Kandara]], [[Domba]], [[Pano (caste)|Pano]],[[Hadi]].<ref name="BehuraMohanty2005">{{cite book|author1=Nab Kishore Behura|author2=Ramesh P. Mohanty|title=Family Welfare in India: A Cross-cultural Study|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=o6Gz0ZDw7PQC&pg=PA49|year=2005|publisher=Discovery Publishing House|isbn=978-81-7141-920-3|pages=49–}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:54, 9 December 2024

ଓଡ଼ିଆ ଲୋକ Odiā Lōka | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 40 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 38,033,000 (2021) | |

| 170,000[1] | |

| 130,000 [2] | |

| 80,000 [3] | |

| 40,000[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Odia | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Minorities:

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryan people , Bonaz people | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Odisha |

|---|

|

| Governance |

| Topics |

|

Districts Divisions |

| GI Products |

|

|

The Odia (ଓଡ଼ିଆ), formerly spelled Oriya, are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group native to the Indian state of Odisha who speak the Odia language. They constitute a majority in the eastern coastal state, with significant minority populations existing in the neighboring states of Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and West Bengal.[5]

History

Ancient period

According to political scientist Sudama Misra, the Kalinga janapada originally comprised the area covered by the Puri and Ganjam districts.[6]

According to some scriptures (Mahabharata and some Puranas), a king Bali, the Vairocana and the son of Sutapa, had no sons. So, he requested the sage, Dirghatamas, to bless him with sons. The sage is said to have begotten five sons through his wife, the queen Sudesna.[7] The princes were named Anga, Vanga, Kalinga, Sumha and Pundra.[8] The princes later founded kingdoms named after themselves. The prince Vanga founded Vanga kingdom, in the current day region of Bangladesh and part of West Bengal. The prince Kalinga founded the kingdom of Kalinga, in the current day region of coastal Odisha, including the North Sircars.[9]

The Mahabharata also mentions Kalinga several more times. Srutayudha, the king of Kalinga, son of Varuna and river Parnasa, had joined the Kaurava camp in the Kurukshetra War. He had been given a divine mace by his father on request of his mother, which protected him as long he wielded it. But, Varuna had warned his son, that using it on a non-combatant will cause the death of the wielder himself. In the frenzy of battle, harried by Arjuna's arrows, he made the mistake of launching it at Krishna, Arjuna's charioteer, who was unarmed. The mace bounced off Krishna and killed Srutayudha. The archer who killed Krishna, Jara Savara, and Ekalavya are said to have belonged to the Sabar people of Odisha.[10]

In the Buddhist text, Mahagovinda Suttanta, Kalinga and its ruler, Sattabhu, have been mentioned.[11]

In the 6th century sutrakara (chronicler), Baudhayana, mentions Kalinga as not yet being influenced by Vedic traditions. He also warns his people from visiting Kalinga (among other kingdoms), saying one who visits it must perform penance.[12]

Medieval period

The Shailodbhava dynasty ruled the region from the sixth to the eighth century. They built the Parashurameshvara Temple in the 7th century, which is the oldest known temple in Bhubaneswar. The ruled Odisha from the 8th to the 10th century. They built several Buddhist monasteries and temples, including Lalitgiri, Udayagiri and Baitala Deula. The Keshari dynasty ruled from the 9th to the 12th century. The Lingaraj Temple, Mukteshvara Temple and Rajarani Temple in Bhubaneswar were constructed during the Bhauma-Kara dynasty.[13] They were introduced as a new style of architecture in Odisha, and the dynasty's rule shifted from Buddhism to Brahmanism.[14]

Modern period

Odisha remained an independent regional power until the early 16th century. It was conquered by the Mughals under Akbar in 1568 and was thereafter subject to a succession of Mughal and Maratha rule before coming under British control in 1803.[15]

In 1817, a combination of high taxes, administrative malpractice by the zamindars and dissatisfaction with the new land laws led to a revolt against Company rule breaking out, which many Odias participated in. The rebels were led by General Jagabandhu Bidyadhara Mohapatra Bhramarbara Raya.[16][17]

Under Maratha control, major Odia regions were transferred to the rulers of Bengal that resulted in successive decline of the language over the course of time in vast regions that stretched until today's Midnapore district of West Bengal.[18][better source needed]

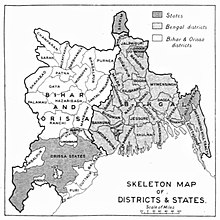

Odisha became a separate province and the first officially recognized language-based state of India in 1936, after the amalgamation of the Odia regions from Bihar and Orissa Province, Madras Presidency and Chhattisgarh Division was successfully executed. 26 Odia princely states, including Sadheikala-Kharasuan in today's Jharkhand, also signed a merger with the newly formed state, while many major Odia-speaking areas were left out due to political incompetence.[19]

Communities

The Odia people are subdivided into several communities such as the Brahmin, Karan, Kayastha, Khandayat, Gopal, Kumuti, Chasa, Bania, Kansari, Gudia, Patara, Tanti, Teli, Badhei, Kamara, Barika, Mali, Kumbhar, Siyal,[20] Sundhi, Keuta, Dhoba, Bauri, Kandara, Domba, Pano,Hadi.[21]

Culture

Religion

In its long history, Odisha has had a continuous tradition of dharmic religions especially Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. Ashoka's conquest of Kalinga (India) made Buddhism a principal religion in the state which led to the establishment of numerous Stupas and non religion learning centres. During Kharavela's reign Jainism found prominence. However, by the middle of the 9th century CE there was a revival of Hinduism as attested by numerous temples such as Mukteshwara, Lingaraja, Jagannath and Konark, which were erected starting from the late 7th century CE. Part of the revival in Hinduism was due to Adi Shankaracharya who proclaimed Puri to be one of the four holiest places or Char Dham for Hinduism. Odisha has, therefore, a syncretic mixture of the three dharmic religions as attested by the fact that the Jagannath Temple in Puri is considered to be holy by Hindus, Buddhists and Jains.

Presently, the majority of people in the state of Odisha are Hindus. As per the census of 2001, Odisha is the third largest Hindu-populated state (as a percentage of population) in India. However, while Odisha is predominantly Hindu it is not monolithic. There is a rich cultural heritage in the state owing to the Hindu faith. For example, Odisha is home to several Hindu saints. Sant Bhima Bhoi was a leader of the Mahima sect movement, Sarala Dasa, was the translator of the epic Mahabharata in Odia, Chaitanya Dasa was a Buddhistic-Vaishnava and writer of the Nirguna Mahatmya, Jayadeva was the author of the Gita Govinda and is recognized by the Sikhs as one of their most important bhagats. Swami Laxmananda Saraswati is a modern-day Hindu saint of Adivasi heritage.

Architecture

The Kaḷinga architectural style is a style of Hindu architecture which flourished in the ancient Kalinga previously known as Utkal and in present eastern Indian state of Odisha. The style consists of three distinct types of temples: Rekha Deula, Pidha Deula and Khakhara Deula. The former two are associated with Vishnu, Surya and Shiva temples while the third is mainly with Chamunda and Durga temples. The Rekha Deula and Khakhara Deula houses are the sanctum sanctorum while the Pidha Deula constitutes outer dancing and offering halls.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Odisha |

|---|

|

| Governance |

| Topics |

|

Districts Divisions |

| GI Products |

|

|

Cuisine

Seafood and sweets dominate Odia cuisine. Rice is the staple cereal and is eaten throughout the day. Popular Odia dishes are rasagolla, rasabali, chhena poda, chhena kheeri, chhena jalebi, chenna jhilli, chhenagaja, khira sagara, dalma, tanka torani and pakhala.[22][23]

Festivals

Ratha yatra

A stunning example of Kalinga architecture is the Jagannath Temple, which was constructed in the twelfth century by King Anantavarman Chodaganga Deva. The goddesses Subhadra, Balabhadra, and Lord Jagannath reside in this hallowed shrine. The festival of Ratha Yatra, which draws pilgrims and visitors from all over the world, is closely linked to the history of the Jagannath Temple.

A wide variety of festivals are celebrated throughout the year; There is a saying in Odia, ‘Baarah maase, terah parba’, that there are 13 festivals in a year. Well known festivals that are popular among the Odia people include the Ratha Yatra, Durga Puja, Rajo, Maha Shivratri, Kartika Purnima, Dola Purnima, Ganesh Puja, Chandan Yatra, Snana Yatra, Makar Mela, Chhau Festival, and Nuakhai.[24]

Religion

Odisha is one of the most religiously and ethnically homogeneous states in India. More than 94% of the people are followers of Hinduism.[25] Hinduism in Odisha is more significant due to the specific Jagannath culture followed by Odia Hindus due to independent rule of Odia Hindu kings. Hinduism flourished in the eastern coastal region under patronage of the Hindu kings: arts, literature, maritime trade, vedic rituals were given importance. The practices of the Jagannath sect is popular in the state and the annual Ratha Yatra in Puri draws pilgrims from across India.[26]

Notable people

- Achyutananda – Indian devotional Poet from Odisha

- Binayak Acharya – Indian politician (1918–1983)

- Afzal-ul Amin – Indian politician and social worker (1915-1983)

- Subroto Bagchi – Indian entrepreneur and business leader

- Bhikari Bal – Indian singer (1929–2010)

- Hemananda Biswal – Indian politician (1939–2022)

- Bhagabat Behera – Indian politician from Odisha (1940–2002)

- Chakradhar Behera – Revolutionary from Odisha, India

- Chandi Prasad Mohanty – Indian Army general

- Sanatan Mahakud – Indian politician

- Krishna Beura – Indian playback singer

- Kadambini Mohakud – Cricketer

- Dutee Chand – Indian sprinter (born 1996)

- Nabakrushna Choudhuri – Indian politician and activist

- Ashok Das – Indian American physicist

- Bibhusita Das – Indian marine engineer

- Bidhu Bhusan Das – Indian academic (1922-1999)

- Bishwanath Das – Indian politician, lawyer, and philanthropist

- Gopabandhu Das – Indian writer (1877–1928)

- Madhusudan Das – Elderly and prominent freedom fighter, lawyer and social reformer from Odisha

- Manoj Das – Indian author (1934–2021)

- Nandita Das – Indian actress, director

- Prabhat Nalini Das – Indian academic

- Shaktikanta Das – Ex-Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

- Anil Dash – American technology executive and entrepreneur

- Rajendra Narayan Singh Deo – Politician from Odisha, India

- Giridhar Gamang – Indian politician

- Hussain Rabi Gandhi – Indian writer and politician (1948–2023)

- Biswabhusan Harichandan – Indian politician (born 1934)

- Mehmood Hussain – Indian filmmaker

- Binod Kanungo – Indian educationalist and author (1912–1990)

- Madhu Sudan Kanungo – gerontologist

- Indrajit Mahanty – Former Chief Justice of Tripura High Court

- Jayanta Mahapatra – Indian poet (1928–2023)

- Harekrushna Mahatab – Indian politician (1899 – 1987)

- Lalit Mansingh – Indian diplomat

- Chaturbhuj Meher – Indian weaver

- Gangadhar Meher – A renowned Odia poet of the 19th century born in Utkala (now known as Odisha)

- Kailash Chandra Meher – Indian artist and painter

- Kunja Bihari Meher – Indian weaver (1928–2008)

- Sadhu Meher – Indian actor, director and producer (1939/1940–2024)

- Atharuddin Mohammed – Dewan of Dhenkanal

- Pramod Kumar Mishra – 13th Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister of India

- Sabyasachi Mishra – Indian film actor

- Baidyanath Misra – Indian economist, educationist, author, and administrator

- B. K. Misra – Neurosurgeon

- Dipak Misra – 45th Chief Justice of India

- Ranganath Misra – 21st Chief Justice of India

- Tapan Misra – Indian scientist

- Biren Mitra – Indian politician (1917–1978)

- Sayeed Mohammed – Indian Odia educationist, freedom fighter and philanthropist

- Anubhav Mohanty – Odia actor and politician

- Baisali Mohanty – Odissi dancer

- Debashish Mohanty – Indian cricketer

- Surendra Mohanty – Odia writer, politician

- Uttam Mohanty – Indian actor

- Bibhu Mohapatra – Indian American Fashion designer

- Kelucharan Mohapatra – Indian classical dancer (1926–2004)

- Sona Mohapatra – Indian singer

- Arabinda Muduli – Odia singer, musician, lyricist (1961-2018)

- Droupadi Murmu – President of India since 2022

- Srabani Nanda – Indian sprinter

- Bibhuti Bhushan Nayak – Indian journalist (born 1965)

- Pragyan Ojha – Former Indian cricketer

- Nila Madhab Panda – Indian film director

- Arun K. Pati – Indian physicist

- Biju Patnaik – Indian politician and aviator (1916-1997)

- Janaki Ballabh Patnaik – Politician from Odisha, India (1927–2015)

- Jayanti Patnaik – Indian parliamentarian and social worker (1932–2022)

- Naveen Patnaik – Indian politician (born 1946)

- Sudarshan Patnaik – Indian Sand Artist

- Sambit Patra – Indian politician (born 1974)

- Devdutt Pattanaik – Indian mythologist and writer (born 1970)

- Dharmendra Pradhan – Indian politician

- Manasi Pradhan – Indian writer and Women's rights activist

- S.N. Pradhan – Director general of police

- Tapan Kumar Pradhan – Indian writer

- Ramakanta Rath – Indian poet from Odisha

- Nilamani Routray – Indian politician (1920–2004)

- Sarojini Sahoo – Indian (Odia) Writer

- Archita Sahu – Indian actress and model

- Jairam Samal – Odia actor

- Debasish Samantray – Indian cricketer (born 1996)

- Biplab Samantray – Indian cricketer (born 1988)

- Pratap Chandra Sarangi – Indian politician

- Nandini Satpathy – Politician from Odisha, India (1931–2006)

- Fakir Mohan Senapati – Indian Odia author

- Sadashiva Tripathy – Chief Minister of Odisha (1910-1980)

- Bijaya Kumar Sahoo – Indian educationalist (1963–2021)

See also

- Odia diaspora

- Folk dance forms of Odisha

- Odia language

- Arts of Odisha

- Kalinga architecture

- Cinema of Odisha

References

- ^ "Odias in the UK". Times Now. 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Census shows Indian population and languages have exponentially grown in Australia". SBS Australia. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Baumann, Martin. "Immigrant Hinduism in Germany". Harvard University.

- ^ "New Zealand". Stats New Zealand. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781598846591.

- ^ Miśra, Sudāmā (1973). Janapada State in Ancient India. Bhāratīya Vidyā Prakāśana.

- ^ Patil, Rajaram D. K. (1973). Cultural History From The Vayu Purana. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. ISBN 978-81-208-2085-2.

- ^ "History of Odisha", Wikipedia, 3 December 2024, retrieved 9 December 2024

- ^ "History of Odisha", Wikipedia, 3 December 2024, retrieved 9 December 2024

- ^ Pati, Rabindra Nath (2008). Family Planning. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-313-0352-8.

- ^ Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (2006). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 978-81-307-0291-9.

- ^ Chatterjee, Suhas (1998). Indian Civilization and Culture. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-7533-083-2.

- ^ Smith, Walter (1994). The Mukteśvara Temple in Bhubaneswar. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-208-0793-8.

- ^ Smith 1994, p. 26.

- ^ GYANENENDRA NATH MITRA (25 December 2019). "Book by British ICS officer covers 'Orissa' as a whole". dailypioneer. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ Sayed Jafar Mahmud (1994). Pillars of Modern India 1757-1947. APH Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-7024-586-5. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "'Paika Bidroha' to be named as 1st War of Independence - NATIONAL - The Hindu". The Hindu.

- ^ Sengupta, N. (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-81-8475-530-5.

- ^ Sridhar, M.; Mishra, Sunita (5 August 2016). Language Policy and Education in India: Documents, contexts and debates. Routledge. ISBN 9781134878246. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ Indian Antiquary: A Journal of Oriental Research in Archaeology, History, Literature, Languages, Folklore Etc. Education Society's Press. 1884.

- ^ Nab Kishore Behura; Ramesh P. Mohanty (2005). Family Welfare in India: A Cross-cultural Study. Discovery Publishing House. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-81-7141-920-3.

- ^ "Cuisine Of Odisha". odishanewsinsight. 16 November 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ "Odia delicacies in Bengaluru's first 'Ama Odia Bhoji' to tickle taste buds". aninews. 12 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ "The tenacious people of Odisha". telanganatoday. 2 December 2018. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Lord Jagannath's Rathyatra as a Marker of Odia Identity". thenewleam. 23 July 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

External links

- ^ Miśra, Sudāmā (1973). Janapada State in Ancient India. Bhāratīya Vidyā Prakāśana.