You Bet Your Life: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

One often-told story recounts the appearance of a woman contestant, Mrs. Story, who mentioned she had nineteen children. Groucho asked, "Why so many children?" The woman said, "Well, I just love my husband." Groucho replied, "And I like a good cigar, but I take it out of my mouth once in a while." The story goes that the remark was judged too risqué to be aired at the time and was edited out before the radio broadcast, but the audio of the audience reaction was used by NBC for many years whenever bring-down-the house laughter was called for in [[laugh track]]s. No copy is thought to survive.<ref>{{Cite web | last = Adams | first = Cecil | author-link = Cecil Adams | title = Did Groucho Marx utter a famous double entendre ad lib on the air? | work = The Straight Dope | date = 1986-07-25 | year = 1986 | url = http://www.straightdope.com/classics/a2_024.html | accessdate = 2007-04-05}}</ref> |

One often-told story recounts the appearance of a woman contestant, Mrs. Story, who mentioned she had nineteen children. Groucho asked, "Why so many children?" The woman said, "Well, I just love my husband." Groucho replied, "And I like a good cigar, but I take it out of my mouth once in a while." The story goes that the remark was judged too risqué to be aired at the time and was edited out before the radio broadcast, but the audio of the audience reaction was used by NBC for many years whenever bring-down-the house laughter was called for in [[laugh track]]s. No copy is thought to survive.<ref>{{Cite web | last = Adams | first = Cecil | author-link = Cecil Adams | title = Did Groucho Marx utter a famous double entendre ad lib on the air? | work = The Straight Dope | date = 1986-07-25 | year = 1986 | url = http://www.straightdope.com/classics/a2_024.html | accessdate = 2007-04-05}}</ref> |

||

The story has taken on the trappings of an [[urban legend]] over the years. Both Groucho and Fenneman denied the incident ever took place. Groucho was interviewed for ''[[Esquire_(magazine)|Esquire]]'' magazine in 1972 and said "I never said that." [[Hector Arce]], Groucho's [[ghost writer]] for his autobiography ''The Secret Word Is Groucho'' inserted the claim that it happened, but Arce compiled the 1976 book from many sources, not |

The story has taken on the trappings of an [[urban legend]] over the years. Both Groucho and Fenneman denied the incident ever took place. Groucho was interviewed for ''[[Esquire_(magazine)|Esquire]]'' magazine in 1972 and said "I never said that." [[Hector Arce]], Groucho's [[ghost writer]] for his autobiography ''The Secret Word Is Groucho'' inserted the claim that it happened, but Arce compiled the 1976 book from many sources, not solely Groucho himself. He probably was unaware Groucho had gone on record denying the claim a few years previously.<ref>{{cite web | title = The Secret Words | work = Snopes | publisher = Snopes.com | date = 2007-01-06 | year = 2007 | url = http://www.snopes.com/radiotv/tv/grouchocigar.asp | accessdate = 2007-04-05 }}</ref> |

||

==Later incarnations of the show== |

==Later incarnations of the show== |

||

Revision as of 14:17, 21 August 2007

| You Bet Your Life | |

|---|---|

| |

| Created by | John Guedel |

| Starring | Groucho Marx George Fenneman |

| Country of origin | |

| No. of episodes | 429 |

| Production | |

| Running time | 30 minutes |

| Original release | |

| Network | NBC |

| Release | October 5, 1950 – June 29, 1961 |

You Bet Your Life was an American radio and television quiz show. The first and most famous version was hosted by Groucho Marx, of Marx Brothers fame, with the unflappable announcer and assistant George Fenneman. The show debuted on radio in 1947, then made the transition to the NBC television network in 1950. The television version was changed very little from the radio version. It was filmed before a studio audience, then slightly edited for television broadcast. In 1960 it was renamed The Groucho Show and ran a further year.

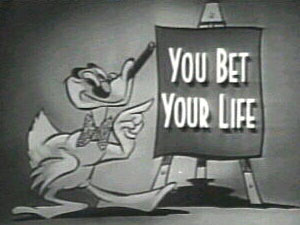

Groucho would be introduced to the music of "Hooray for Captain Spaulding", his signature song introduced in the 1930 film Animal Crackers. Fenneman would say, "Here he is, the one, the ONLY..." and the audience would finish with a thunderous "GROUCHO!" In the early years Groucho would feign surprise: "Oh that's ME, Groucho Marx!" Much of the tension of the show revolved around whether any of the contestants, in pre-contest conversation with Groucho, would say the "secret word", a common word seemingly selected at random and revealed to the audience at the show's outset. If a contestant uttered the word, a toy duck made to resemble Groucho with a mustache, eyeglasses and with a cigar in its bill, would descend from the ceiling to bring the contestant $50. (In one special episode, Groucho's brother, Harpo came down instead.) Marx would sometimes slyly direct their conversation in such a way as to encourage the word to come up. The contestants were paired individuals, usually of the opposite sex. Sometimes celebrities would be paired with "ordinary" people, and it was not uncommon for the contestants to have some sort of newsworthiness about them. For example, one episode aired soon after the end of the Korean War featured Janet Wang, a Korean-American contestant who had been a prisoner of war.

In the contest itself, contestants would choose among available categories and then try to answer a series of questions dealing with the chosen category. One popular category involved attempting to name a United States state after being given a number of cities and towns within the state. The format of the game at the beginning was that each couple started with $20. They were asked 4 questions in their given category. For each question, they bet up to all of their money. According to co-director Robert Dwan in his book, As Long As They're Laughing, producer John Guedel changed this because too many couples were betting--and losing--all their money. He changed the format to having couples start with $100, then pick four questions worth from $10 to $100. A correct answer added the value of the question; an incorrect answer cut the previous total in half, so that a couple that answered the $70, $80, $90, and $100 questions would end up with $440; missing all four questions would reduce their total to $6.25 (augmented to $25 with a question such as 'Who's buried in Grant's Tomb?'). Later, this was changed to couples answering questions either until they got 2 consecutive questions in a row wrong or answered 4 consecutive questions correctly for a prize of $1,000. Toward the end (1959-61), contestants picked four questions worth $100, $200, or $300; they could win up to $1200 but needed only $500 to qualify for the jackpot question. The two contestants worked together ("Remember, only one answer between you."). In all formats, a final question was asked for a jackpot amount for the couple who had gotten the highest total amount during the game. If the couple bet all of their money at any point and lost (or if they ended up below $25), they were asked a consolation question for $25. Consolation questions were made easy, in hopes that no one would miss them, although some people did. The questions were in the style of "Who was buried in Grant's tomb?" "When did the War of 1812 start?" "How long do you cook a three-minute egg?" and "What color is an orange?" In addition to the quiz prizes was the famous secret-word duck. Eventually, the prize was $100 for saying the secret word. The famous "secret-word duck" was replaced from time to time with a wooden Indian figure. In the early years (1947-56), the jackpot question started at $1000, with $500 added each week until someone correctly answered the question. With the coming of the big-money quizzes, contestants faced a wheel with numbers from one to ten; one contestant picked a number for $10,000; the other picked one for $5000. The wheel was spun; if either number came up, the question was worth that amount of money, else the question was worth $2000. From 1956-59 contestants risked half their $1000 won in the quiz on a shot at the wheel; from 1959-61 they risked nothing. Groucho always reminded contestants that "I'll give you fifteen seconds to decide on a single answer. Think carefully and please, no help from the audience." Then a bit of "Captain Spaulding" was used as "think" music.

The play of the game, however, was secondary to the interplay between Groucho, the contestants, and occasionally Fenneman. The program was hugely successful and was rerun into the 1970s, and later in syndication, in some markets under the title The Best of Groucho. As such, it was the first game show to have its reruns syndicated.

The radio program was sponsored by Elgin American. Early seasons of the television show were sponsored by Plymouth automobiles, with advertisements for their vehicles (most notably the DeSoto) incorporated into the opening credits and the show itself. Each show would end with Groucho sticking his head through a hole in the DeSoto logo and say "When you go into your DeSoto dealer tomorrow, tell them Groucho sent you."

Since most of the series was filmed, many episodes have survived and have been available in television syndication for years. A number of episodes have also been released to DVD. The pilot episode for the TV version which was originally by CBS is also intact.

Seven months after You Bet Your Life ended its 11-season run at NBC, Groucho had another game show in prime-time. It was titled Tell It to Groucho which aired on CBS during the winter and spring months of 1962.

There was a parody of this show on the Jack Benny Show, in which Jack pretends to be someone else to get on Groucho's show, and continually blabs in an effort to say the secret word ("telephone"). He gets it by accident when he says he can "tell a phony". However, he is unable to answer the final question, which ironically is about Jack Benny, simply because it asks his real age, which Jack would never give voluntarily. This episode, after its original screening, could only be watched at Groucho's home on film, and even then only if you were invited to see it. After Groucho's death the film eventually appeared in the Unknown Marx Brothers documentary on DVD.

The cigar incident

One often-told story recounts the appearance of a woman contestant, Mrs. Story, who mentioned she had nineteen children. Groucho asked, "Why so many children?" The woman said, "Well, I just love my husband." Groucho replied, "And I like a good cigar, but I take it out of my mouth once in a while." The story goes that the remark was judged too risqué to be aired at the time and was edited out before the radio broadcast, but the audio of the audience reaction was used by NBC for many years whenever bring-down-the house laughter was called for in laugh tracks. No copy is thought to survive.[1]

The story has taken on the trappings of an urban legend over the years. Both Groucho and Fenneman denied the incident ever took place. Groucho was interviewed for Esquire magazine in 1972 and said "I never said that." Hector Arce, Groucho's ghost writer for his autobiography The Secret Word Is Groucho inserted the claim that it happened, but Arce compiled the 1976 book from many sources, not solely Groucho himself. He probably was unaware Groucho had gone on record denying the claim a few years previously.[2]

Later incarnations of the show

1980 Buddy Hackett Version

In 1980, Buddy Hackett hosted a similar show with the same title which failed to run a single full season.

Three individual contestants appeared on the show, one at a time, to be interviewed by Hackett, and then played a True or False quiz of five questions in a particular category. The first correct answer to a question earned $25, and the amount would double with each subsequent correct answer. After the fifth question, the contestant could opt to try to correctly answer a sixth question. If correct, his/her earnings were tripled; incorrect, the earnings were cut in half. Maximum winnings were $1200.

The secret word was still worth $100.

The contestant with the most money won, came back on stage at the end of the show, to meet "Leonard," the prize duck, where they would stop a rotating device, causing a plastic egg to drop out, which concealed the name of a nice bonus prize to go with their cash winnings.

Original YBYL announcer George Fenneman appeared one time as a guest, and played the game for a member of the audience.

1988 Richard Dawson Pilot

Richard Dawson hosted a pilot for a potential revival in 1988, but NBC declined to pick up the show.

Two teams of two unrelated players came out one team at a time and were asked three questions, either $100, $150 or $200. Later, both teams came out and played four questions each at either $200, $300 or $400. The team with the most money at the end of this round went onto a bonus game. The secret word was around, but since it was never guessed, it's unknown whether the duck survived for this pilot, or of its value.

In the bonus game, sidekick Steve Carlson read questions with either true or false answers. The players locked in their answers over a 30 second period. If the players match on 5 answers and their matched answer is correct, the team won $5000. If they don't reach five, they earn $200 per correct match.

1992 Bill Cosby Version

Marx had suggested to Bill Cosby that he could do the show, when Cosby was still a struggling young comic. Marx died in 1977, but it was not until 1992 that Cosby pursued his suggestion and taped a season of the program for the syndication market.

The Main Game

In this version three couples competed, each one played the game individually. When each one came out, they usually spend some time talking with Cosby. When the interview was done, the game began. Each couple started at $750, and host Cosby gave a category & asked three questions under that category. Before each question, the couple in play made a bet based on how much they know about the category. A correct answer adds the wager, but an incorrect answer deducts the wager. The Secret Word in this version was worth $500. Maximum winnings, therefore, were $6,500 (including the Secret Word).

The $10,000 Bonus Game

The couple with the most money goes on to play for $10,000 in cash. In this game, the winning couple got to answer one last question on any given subject. An incorrect answer ends the game, but a correct answer won a choice of three envelopes (which are all attached to the blackbird, this version's duck who wore a Temple University [Cosby's alma mater] sweater). Two of the envelopes had the bird's head on it, choosing one of them doubles the couple's money; while only one adds $10,000 to the winning couple's total.

The show's results were so unsatisfactory that most of the stations who initially bought it soon either stopped showing it entirely or moved it to a time slot in the middle of the night, and it was canceled after one season.

Trivia

- Phyllis Diller appeared as a contestant on the show before she became famous, and reportedly gave back to Groucho as snappily as he gave her.

- The "easy" consolation prize question "Who's buried in Grant's Tomb?" actually is quite tricky. First, since Grant's Tomb is above ground, no one is technically "buried" in it at all. Secondly, it contains the sarcophagi of both President Grant and his wife, who presumably would both have to be mentioned for an accurate answer.

- Voice actor Daws Butler appeared as a contestant. No one in the audience knew who he was until he began speaking in Huckleberry Hound's voice. He and his partner went on to win the $10,000 top prize.

- Spanish language stand-up comic Pedro Gonzalez-Gonzalez appeared on the show as a contestant. He parlayed his appearance into a career as a character actor, playing mostly comic relief roles in Westerns.

- Authors Ray Bradbury and William Peter Blatty both appeared on the show; Blatty won $10,000 and used the leave of absence the money afforded him to write The Exorcist.

- Bill Cosby won a Kid's Choice Award while he was doing the show.

References

- ^ Adams, Cecil (1986-07-25). "Did Groucho Marx utter a famous double entendre ad lib on the air?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "The Secret Words". Snopes. Snopes.com. 2007-01-06. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

External links

- Peabody Award winners

- Game shows

- American radio programs

- NBC network shows

- First-run syndicated television programs

- 1950 television program debuts

- 1950s American television series

- 1960s American television series

- 1980s American television series

- 1990s American television series

- 1993 television program series endings