Dominican Republic: Difference between revisions

Removed the Name section: doesn't seem to be essential info, and it's unsourced. |

|||

| Line 281: | Line 281: | ||

The country is a member of the following international organizations:<ref name=CIADemo/> |

The country is a member of the following international organizations:<ref name=CIADemo/> |

||

[[ACP countries|ACP]], [[Caribbean Community|Caricom]] (observer), [[United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean|ECLAC]], [[Food and Agriculture Organization|FAO]], [[Group of 77|G-77]], [[Inter-American Development Bank|IADB]], [[International Atomic Energy Agency|IAEA]], [[International Bank for Reconstruction and Development|IBRD]], [[International Civil Aviation Organization|ICAO]], [[International Chamber of Commerce|ICC]], [[International Criminal Court|ICCt]], [[International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement|ICRM]], [[International Development Association|IDA]] (graduate), [[International Fund for Agricultural Development|IFAD]], [[International Finance Corporation|IFC]], [[International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies|IFRCS]], [[International Hydrographic Organization|IHO]] (suspended), [[International Labour Organization|ILO]], [[International Monetary Fund|IMF]], [[International Maritime Organization|IMO]], [[Intelsat]] (or ITSO), [[Interpol]], [[International Olympic Committee|IOC]], [[International Organization for Migration|IOM]], [[Inter-Parliamentary Union|IPU]], [[International Organization for Standardization|ISO]] (correspondent member), [[International Telecommunication Union|ITU]], [[International Trade Union Confederation|ITUC]], [[Latin American Economic System|LAES]], [[Latin American Integration Association|LAIA]] (observer), [[Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency|MIGA]], [[Non-Aligned Movement|NAM]], [[Organization of American States|OAS]], [[OPANAL]], [[Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons|OPCW]] (signatory), [[Permanent Court of Arbitration|PCA]], [[Rio Group]], [[United Nations|UN]], [[United Nations Conference on Trade and Development|UNCTAD]], [[UNESCO]], [[United Nations Industrial Development Organization|UNIDO]], [[Latin Union|Unión Latina]], [[United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire|UNOCI]], [[World Tourism Organization|UNWTO]] (or WToO), [[Universal Postal Union|UPU]], [[World Customs Organization|WCO]], [[World Federation of Trade Unions|WFTU]], [[World Health Organization|WHO]], [[World Intellectual Property Organization|WIPO]], [[World Meteorological Organization|WMO]], [[World Trade Organization|WTO]] (or WTrO). |

[[ACP countries|ACP]], [[Caribbean Community|Caricom]] (observer), [[United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean|ECLAC]], [[Food and Agriculture Organization|FAO]], [[Group of 77|G-77]], [[Inter-American Development Bank|IADB]], [[International Atomic Energy Agency|IAEA]], [[International Bank for Reconstruction and Development|IBRD]], [[International Civil Aviation Organization|ICAO]], [[International Chamber of Commerce|ICC]], [[International Criminal Court|ICCt]], [[International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement|ICRM]], [[International Development Association|IDA]] (graduate), [[International Fund for Agricultural Development|IFAD]], [[International Finance Corporation|IFC]], [[International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies|IFRCS]], [[International Hydrographic Organization|IHO]] (suspended), [[International Labour Organization|ILO]], [[International Monetary Fund|IMF]], [[International Maritime Organization|IMO]], [[Intelsat]] (or ITSO), [[Interpol]], [[International Olympic Committee|IOC]], [[International Organization for Migration|IOM]], [[Inter-Parliamentary Union|IPU]], [[International Organization for Standardization|ISO]] (correspondent member), [[International Telecommunication Union|ITU]], [[International Trade Union Confederation|ITUC]], [[Latin American Economic System|LAES]], [[Latin American Integration Association|LAIA]] (observer), [[Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency|MIGA]], [[Non-Aligned Movement|NAM]], [[Organization of American States|OAS]], [[OPANAL]], [[Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons|OPCW]] (signatory), [[Permanent Court of Arbitration|PCA]], [[Rio Group]], [[United Nations|UN]], [[United Nations Conference on Trade and Development|UNCTAD]], [[UNESCO]], [[United Nations Industrial Development Organization|UNIDO]], [[Latin Union|Unión Latina]], [[United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire|UNOCI]], [[World Tourism Organization|UNWTO]] (or WToO), [[Universal Postal Union|UPU]], [[World Customs Organization|WCO]], [[World Federation of Trade Unions|WFTU]], [[World Health Organization|WHO]], [[World Intellectual Property Organization|WIPO]], [[World Meteorological Organization|WMO]], [[World Trade Organization|WTO]] (or WTrO). |

||

==Name== |

|||

For most of its history (up to independence) the colony was known by the name of its present capital, Santo Domingo. At present, it is one of the few countries in the world with a [[demonym]]-based description serving as a name. For example, the [[French Republic]] is known as France, the American republic is known as the United States of America, but the Dominican Republic has no such equivalent. |

|||

==Provinces and municipalities== |

==Provinces and municipalities== |

||

Revision as of 17:47, 4 July 2008

Dominican Republic República Dominicana | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Dios, Patria, Libertad" (Spanish) "God, Homeland, Liberty" | |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Santo Domingo 1 |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Ethnic groups | 73% Multiracial, 16% White (Spanish, Italians, French, others), 11% Black |

| Demonym(s) | Dominican |

| Government | Presidential republic |

| Leonel Fernández | |

| Rafael Alburquerque | |

| Independence From Haiti | |

• Date | 27 February 1844 |

| Area | |

• Total | 48,730 km2 (18,810 sq mi) (130th) |

• Water (%) | 1.6 |

| Population | |

• July 2007 estimate | 9,760,000 (82nd) |

• 2000 census | 9,365,818 |

• Density | 201/km2 (520.6/sq mi) (38th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate |

• Total | $89.87 billion (62nd) |

• Per capita | $9,208 (71st) |

| Gini (2003) | 51.7 high inequality |

| HDI (2005) | Error: Invalid HDI value (79th) |

| Currency | Peso (DOP) |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (Atlantic) |

| Calling code | 1 |

| ISO 3166 code | DO |

| Internet TLD | .do |

| |

The Dominican Republic (Spanish: República Dominicana, Spanish pronunciation: [reˈpuβlika ðominiˈkana]) is a nation located in the Caribbean region's island of Hispaniola. Part of the Greater Antilles archipelago, Hispaniola lies west of Puerto Rico and east of Cuba and Jamaica.[2] Its western third is the nation of Haiti, making Hispaniola one of two Caribbean islands that are occupied by two countries, Saint Martin being the other.

The Dominican Republic is the site of the first permanent European settlement in the Americas, its capital Santo Domingo, which was also the first colonial capital in the Americas.[3] It is the site of the first cathedral,[1] university, European-built road, European-built fortress, and more.

For most of its independent history, the nation experienced political turmoil and unrest, suffering through many non-representative and tyrannical governments. Since the death of military dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina in 1961, the Dominican Republic has moved toward representative democracy.

History

The Taínos

Hispaniola was inhabited by the Taínos, an Arawakan-speaking people who may have arrived around A.D. 600, displacing earlier inhabitants.[4] The Taínos called the island Kiskeya or Quisqueya, meaning "highest land", as well as Haití or Aytí, and Bohio.[5] They engaged in farming and fishing,[6] and hunting and gathering.[4] There are widely varying estimates of the population of Hispaniola in 1492, including one hundred thousand,[7] three hundred thousand,[4] three million,[8] and seven to eight million.[9] By 1492 Hispaniola was divided into five chiefdoms.[10]

Spanish rule

Christopher Columbus landed at Môle Saint-Nicolas, in northwest present-day Haiti, on December 5 1492, during his first voyage and claimed the island for Spain, which he named La Española. Nineteen days later his flagship the Santa Maria ran aground near the present site of Cap-Haitien. Columbus was forced to leave 39 men, founding the settlement of La Navidad. He then moved east, exploring the northern coast of what is now the Dominican Republic, after which he returned to Spain. He sailed back to America three more times.

After initially friendly relations, the Taínos resisted the conquest. One of the earliest leaders to fight against the Spanish was the female Chief Anacaona of Xaragua, in the southwest, who married Chief Caonabo of Maguana in the center and south of the island. She was captured by the Spanish and executed in front of her people. Other notables who resisted include Chief Guacanagari, Chief Guamá, and Chief Hatuey, who later fled to Cuba and helped fight the Spaniards there. Chief Enriquillo fought victoriously against the Spaniards in the Baoruco Mountain Range, in the southwest, to gain freedom for himself and his people in a part of the island for a time.

By the mid-1500s the majority of Taíno people had died from mistreatment, diseases to which they had no immunity, suicide, the breakup of family unity, starvation,[4] forced labor, torture, and war with the Spaniards. Most scholars now believe that, among the various contributing factors, infectious disease was the overwhelming cause of the population decline of the indigenous people.[11] The Taíno survived mostly in racially mixed form, and today most Dominicans have Taíno ancestry.[12][13]

Some scholars believe that Bartolomé de las Casas exaggerated[14] the Indian population decline in an effort to persuade King Carlos to intervene, and that encomenderos also exaggerated it, in order to receive permission to import more African slaves. Moreover, censuses of the time did not account for the number of Indians who fled into remote communities,[12] where they often joined with runaway Africans, called cimarrones, producing zambos. There were also confusing issues with racial categorization, as Mestizos who were culturally Spanish were counted as Spaniards.[12]

In 1496 Bartolomeo Columbus, Christopher's brother, built the city of Nueva Isabela (New Isabella), now Santo Domingo, in the south of Hispaniola. It was one of the first Spanish settlements, and became Europe's first permanent settlement in the "New World".

The Spaniards created a plantation economy on Hispaniola, particularly from the second half of the 16th century.[7] The island became a springboard for European conquest of the Caribbean islands, called Antilles, and soon after, the American mainland.

For decades Santo Domingo colony was the headquarters of Spanish colonial power in the New World. With the Spanish conquest of the mainland empires of the Aztecs and Incas, the importance of Hispaniola declined and Spain paid less attention to it. French bucaneers settled in the western part of the island; By the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Spain ceded that part of Hispaniola to France. It grew into the wealthy colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), with four times (500,000 vs. 125,000) as much population as Spanish Santo Domingo by the end of the 18th century.[15]

French rule

France came to own the whole island in1795, when by the Treaty of Basel Spain ceded Santo Domingo as a consequence of the French Revolutionary Wars. At the time slaves led by Toussaint Louverture in the western part (Haiti) were in revolt against France. In 1801 Toussaint Louverture captured Santo Domingo from the French, thus gaining control of the entire island.

In 1802 an army sent by Napoleon captured Toussaint Louverture and sent him to France as prisoner. Toussaint Louverture's successors, and yellow fever, succeeded in expelling the French again from Saint-Domingue. The nation declared independence as Haiti in 1804.

France went on to recover Spanish Santo Domingo. In 1808, following Napoleon's invasion of Spain, the criollos of Santo Domingo revolted against French rule, and with Great Britain's (Spain's ally) and Haiti's help,[16] returned Santo Domingo to Spanish control.[17]

The Ephemeral Independence and Haitian rule

After a dozen years of Spanish rule and failed independence plots by various groups, former Spanish Lieutenant-Governor José Núñez de Cáceres declared the colony's independence as the state of Haití Español (Spanish Haiti) on November 30, 1821. He requested admission to Simón Bolívar's nation of Gran Colombia. But the new nation's independence was short-lived. Haitian forces, led by Jean-Pierre Boyer, invaded just nine weeks later in February 1822.[18]

As Toussaint Louverture had done the first time, the Haitians abolished slavery. But they nationalized all public property; most private property, including all the property of landowners who had left in the wake of the invasion; much Church property; as well as all property belonging to the former rulers, the Spanish Crown. All levels of education suffered collapse; the university was shut down, as it was starved of resources and all Dominican men from 16 to 25-years-old were drafted into the Haitian army. Haiti imposed a "heavy tribute" on the Dominican people.[19] Many whites fled Santo Domingo for Puerto Rico and Cuba — both still under Spanish rule — Venezuela, and elsewhere.

Boyer changed the Dominican economic system to place more emphasis on cash crops to be grown on large plantations, reformed the tax system, and allowed foreign trade. But the new system was widely opposed by Dominican farmers, although it produced a boom in sugar and coffee production. Boyer's troops, which included many Dominicans, were unpaid, and had to "forage and sack" from Dominican civilians. In the end the economy faltered and taxation became more onerous. Rebellions occurred even by freed Dominican slaves, while Dominicans and Haitians worked together to oust Boyer from power. Anti–Haitian movements of several kinds — pro–independence, pro–Spanish, pro–French, pro–British, pro–United States — gathered force following Boyer's overthrow in 1843.[19]

Independence

In 1838 Juan Pablo Duarte founded a secret society called La Trinitaria that sought pure and simple independence of Santo Domingo without any foreign intervention.[20] Ramón Matías Mella and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez (the latter of partly African ancestry),[21] despite not being among the founding members of Trinitaria, were decisive in the fight for independence. They are now hailed, together with Duarte, as the Founding Fathers of the Dominican Republic. On February 27, 1844, the Trinitarios, as the members of La Trinitaria were known, declared independence from Haiti. They were backed by Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle-rancher from El Seibo who became general of the army of the nascent Republic and is known as "El Liberador." The Dominican Republic's first Constitution was adopted on November 6, 1844, and was modeled after the United States Constitution.[6]

The decades that followed were filled with tyranny, factionalism, economic difficulties, rapid changes of government, and exile for political opponents. Threatening the nation's independence were renewed Haitian invasions occurring in 1844, 1845-49, 1849-55, and 1855-56.[19]

Meanwhile, archrivals Santana and Buenaventura Báez held power most of the time, both ruling arbitrarily. They promoted competing plans to annex the new nation to another power: Santana favored Spain, and Báez the United States.

The voluntary colony and the Restoration republic

In 1861, after silencing or exiling many of his opponents and mainly due to political and economic reasons, Santana signed a pact with the Spanish Crown and reverted the Dominican nation to a colonial status,[22] the only Latin American country to do so. Opponents launched the War of the Restoration in 1863, led by a group of men including Santiago Rodríguez and Benito Monción among others; General Gregorio Luperón distinguished himself at the end of the war. Haitian authorities, fearful of the re-establishment of Spain as colonial power on their border, gave refuge and logistics to Dominican revolutionaries to re-establish independence.[22] The United States, then fighting its own Civil War, vigorously protested the Spanish action. After two years of fighting, the Spanish troops abandoned the island.[22] The Restoration was proclaimed on August 16, 1863.

Political strife again prevailed in the years that followed; warlords ruled, military revolts were extremely common, and the nation amassed debt. In 1869 it was the turn of Báez to act on his plan of annexing the country to the United States,[18] with a payment of 1.5 million dollars by the U.S. as part of the deal, in order to alleviate the Dominican Republic's debts.[23][6] U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant supported this plan, but the United States Senate refused on June 30, 1870,[18] albeit by just one vote. President Grant thought that former American slaves could go to the Dominican Republic and live in peace, free of harassment by Southern whites.[24]

Báez was toppled in 1874, returned, and was toppled for good in 1878. A new generation was now entirely in charge, with the passing of Santana (he died in 1864) and Báez from the scene. Relative peace came to the country in the 1880s,[25] which saw the coming to power of General Ulises Heureaux.

The new president was initially popular.[26] He was, however, "a consummate dissembler", who put the nation deep into debt while using much of the proceeds for his personal use and to maintain his police state.[26] Heureaux's rule became more despotic with time and he all the more unpopular.[27][26] In 1899 he was assassinated. However, the unprecentedly long calm over which he'd presided allowed for some improvement in the Dominican economy. The sugar industry was modernized,[28] and the country attracted foreign workers and immigrants, both from the Old World and the New.

From 1902 on, short-lived governments were again the norm and provincial leaders held much of the power. Furthermore, the national government was bankrupt and, unable to pay its debts, faced the threat of military intervention by France and other European powers seeking repayment.

U.S. intervention

It was this situation that U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt sought to prevent, in great part in order to protect the vicinity of the Panama Canal, which was then under construction.[26] He made a small military intervention to ward off the European powers, proclaimed his famous Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, and in 1906 the Dominican Republic and the United States entered into a 50-year treaty giving control of customs administration to the United States.[6] In exchange the United States agreed to use the customs proceeds to help reduce the immense foreign debt of the Dominican Republic,[6] and even assumed responsibility for said debt.[26]

In 1914, the United States, due to extreme political internal instability in the Dominican Republic (inability to elect a president), expressed concern and stated that a leader must be elected, or the United States would impose one.[29] As a result, Ramón Báez Machado was elected provisional president on August 27, 1914.[29] Presidential elections held on October 25 returned Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra to the presidency. Despite his victory, however, Jimenes felt impelled to appoint leaders and prominent members of the various political factions to positions in his government in an effort to broaden its support. The internecine conflicts that resulted had quite the opposite effect, weakening the government and the President and emboldening Secretary of War Desiderio Arias to take control of both the armed forces and the Congress, which he compelled to impeach Jimenes for violation of the constitution and the laws. Although the United States ambassador offered military support to his government, Jimenes opted to step down on May 7 1916.

Arias never assumed the presidency formally. The United States government, apparently tired of its recurring role as mediator, had decided to take more direct action. By this time, U.S. forces were occupying Haiti. The initial military administrator of Haiti, Rear Admiral William Caperton, had actually forced Arias to retreat from Santo Domingo by threatening the city with naval bombardment on May 13, 1916.

U.S. occupation

The first Marines landed three days later, on May 19 1916. Although they established effective control of the country within two months, the United States forces did not proclaim a military government until November. Most Dominican laws and institutions remained intact under military rule, although the shortage of Dominicans willing to serve in the Cabinet forced the military governor, Harry Shepard Knapp, to fill a number of portfolios with United States naval officers. The press and radio were censored for most of the occupation, and public speech was limited in the meantime.

The surface effects of the occupation were largely positive. The Marines restored order throughout most of the republic (with the exception of the eastern region); the country's budget was balanced, its debt was diminished, and economic growth resumed. Infrastructure projects produced new roads that linked all the country's regions for the first time in its history. A professional military organization, the Dominican Constabulary Guard, replaced the partisan forces that had waged a seemingly endless struggle for power. Most Dominicans, however, greatly resented the loss of their sovereignty to foreigners, few of whom spoke Spanish or displayed much real concern for the welfare of the republic.

The most intense opposition to the occupation arose in the eastern provinces of El Seibo and San Pedro de Macorís. From 1917 to 1921, the United States forces battled a guerrilla movement in that area known as the "gavilleros". The guerrillas enjoyed considerable support among the population, and they benefited from a superior knowledge of the terrain. The movement survived the capture and the execution of its leader, Vicente Evangelista, and some initially fierce encounters with the Marines. However, the gavilleros eventually yielded to the occupying forces' superior firepower, air power (a squadron of six Curtis Jennies), and determined (often brutal) counter-insurgency methods.

After World War I, public opinion in the United States began to run against the occupation. U.S. President Warren G. Harding, who succeeded Woodrow Wilson in March 1921, had campaigned against the occupations of both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In June 1921, United States representatives presented a withdrawal proposal, known as the Harding Plan, which called for Dominican ratification of all acts of the military government, approval of a loan of US$2.5 million for public works and other expenses, the acceptance of United States officers for the constabulary — now known as the Guardia Nacional (National Guard) — and the holding of elections under United States supervision.

Popular reaction to the plan was overwhelmingly negative. Moderate Dominican leaders, however, used the plan as the basis for further negotiations that resulted in an agreement allowing for the selection of a provisional president to rule until elections could be organized. Under the supervision of High Commissioner Sumner Welles, Juan Bautista Vicini Burgos assumed the provisional presidency on October 21, 1922. In the presidential election of March 15, 1924, former President Horacio Vásquez Lajara handily defeated Francisco J. Peynado. Vásquez's Alliance Party (Partido Alianza) also won a comfortable majority in both houses of Congress. With his inauguration on July 13, control of the republic returned to Dominican hands. He gave the country six years of good government, in which political and civil rights were respected and the economy grew strongly, in an atmosphere of peace.[30]

Trujillo era

The Dominican Republic was ruled by dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo from 1930 until his assassination in 1961. Trujillo ruled with an iron fist, persecuting anyone who opposed his regime. There was considerable economic growth during his rule, although a great deal of the wealth went to the dictator and other regime elements. He also renamed many towns and provinces after himself and members of his family, including the capital city Santo Domingo, renamed Ciudad Trujillo (Trujillo City).

In 1937 Trujillo (who was himself one-quarter Haitian),[31] in an event known as the Parsley Massacre or in the Dominican Republic as El Corte (The Cutting),[32] ordered the Army to kill Haitians on the Dominican side of the border. An estimated 17,000 to 35,000 Haitians were killed over approximately five days, from the night of October 2, 1937 through October 8 1937. Haitians were cut down with machetes.[31][18] The soldiers of Trujillo would go out and interrogate anyone with dark skin, hold up a sprig of perejil (parsley) and pronounce what they were holding up. Haitians who spoke French and/or Kreyol said the "r" in perejil with a flat long pronunciation, while Dominicans said it with a trilled "r" sound.[32] This massacre was alleged to have been an attempt to seize money and property from Haitians living on the border.[33] As a result of this massacre the Dominican Republic agreed to pay Haiti US $750,000 which was later reduced to $525,000.[34][22] The Dominican government headed by Trujillo for a long time was supported by the USA,[35] the Catholic Church, and the Dominican elite; even after the death of Dominicans in the political opposition and over 17,000 Haitians.[32] Trujillo was assassinated on May 30, 1961 in Santo Domingo.

Post-Trujillo

A democratically-elected government under leftist Juan Bosch took office in 1963, but was overthrown later in the year. After nineteen months of military rule, a pro-Bosch revolt took place in 1965. US Marines arrived in the Dominican Republic to restore order in Operation Powerpack, later to be joined by forces from the Organization of American States.[36] They remained in the country for over a year and left after supervising elections which led to the victory of Joaquín Balaguer, who had been Trujillo's last puppet president, over Bosch.

Balaguer remained in power as president for 12 years. His tenure was a period of repression of civil liberties, presumably to prevent pro-Cuba or pro-communist parties from gaining power in the country. His rule was also criticized for a growing disparity between rich and poor and praised for an ambitious infrastructural program which included housing, theaters, museums, aqueducts, roads, highways and the massive Columbus' Lighthouse which was completed in a subsequent tenure in 1992.

1978 to present

In 1978, Balaguer was succeeded in the presidency by opposition candidate Antonio Guzmán Fernández, of the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD). From 1978 to 1986, the Dominican Republic experienced a period of relative freedom and basic human rights. Balaguer regained the presidency in 1986, and was re-elected in 1990 and 1994, defeating PRD candidate José Francisco Peña Gómez, a former mayor of Santo Domingo. Both the national and international communities generally viewed these elections as a major fraud, leading to political pressure for Balaguer to step down.[citation needed] Balaguer responded by scheduling another presidential contest in 1996, which was won by Bosch's Dominican Liberation Party for the first time, with Leonel Fernández as its candidate. In 2000 Hipólito Mejía won the electorate when opposing candidates Danilo Medina and a very old Joaquín Balaguer decided that they would not force a runoff after the first got 49.8% of the votes. In 2004 Leonel Fernández was elected again, with 57% of the votes, defeating then-incumbent president Mejía. In 2008, President Leonel Fernández was reelected with 53.83% of the vote against Miguel Vargas Maldonado of the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD), a former minister under Hipólito Mejía's government, who achieved a 30.5%. Amable Aristy of Joaquin Balaguer's once prosperous Social Christian Reformist Party (Partido Reformista Social Cristiano) achieved a mere 4.59% of the vote. Other minority candidates, which include former Attorney General Guillermo Moreno from the Movement for Independence, Unity and Change (Movimiento Independencia, Unidad y Cambio aka MIUCA) and Social Christian Reformist Party (Partido Reformista Social Cristiano) former presidential candidate and defector Eduardo Estrella, obtained less than 1% of the vote.

Government and politics

The Dominican Republic is a representative democracy, with national powers divided among independent executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The President of the Dominican Republic appoints the cabinet, executes laws passed by the legislative branch, and is commander in chief of the armed forces. The president and vice president run for office on the same ticket and are elected by direct vote for 4-year terms. Legislative power is exercised by a bicameral Congress composed of the Senate (with 32 members) and the Chamber of Deputies (with 178 members).

The Dominican Republic has a multi-party political system with national elections every 2 years (alternating between presidential elections and congressional/municipal elections). Presidential elections are held in years evenly divisible by four. Congressional and municipal elections are held in even numbered years not divisible by four. International observers have found that presidential and congressional elections since 1996 have been generally free and fair. Elections are supervised by a Central Elections Board (JCE) of 9 members chosen for a four-year term by the newly elected Senate. JCE decisions on electoral matters are final.

Under the constitutional reforms negotiated after the 1994 elections, the 16-member Supreme Court of Justice is appointed by a National Judicial Council, which comprises the President, the leaders of both houses of Congress, the President of the Supreme Court, and an opposition or non-governing-party member. One other Supreme Court Justice acts as secretary of the Council, a non-voting position. The Supreme Court has sole authority over managing the court system and in hearing actions against the president, designated members of his cabinet, and members of Congress when the legislature is in session.

The Supreme Court hears appeals from lower courts and chooses members of lower courts. Each of the 31 provinces is headed by a presidentially appointed governor. Mayors and municipal councils to administer the 124 municipal districts and the National District (Santo Domingo) are elected at the same time as congressional representatives.[37]

Politics

The Dominican Republic holds elections every four years at the congressional levels as well as every four years at the presidential levels. The country becomes highly politicized, as millions of dollars are spent in propaganda and campaigning. The political system is characterized by clientelism, which has corrupted the system throughout the years.[38]

There are many political parties and interest groups and, new in this scenario, civil organizations. The three major parties are the conservative Social Christian Reformist Party (Spanish: Partido Reformista Social Cristiano [PRSC]), in power 1966–78 and 1986–96; the social democratic Dominican Revolutionary Party (Spanish: Partido Revolucionario Dominicano [PRD]), in power in 1963, 1978–86, and 2000–04); and the increasingly conservative Dominican Liberation Party (Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana [PLD]), in power 1996–2000 and since 2004.

The presidential elections of 2008 were held on May 16, 2008, with incumbent Leonel Fernandez winning with 53% of the vote.[39] This would be Fernández's third, and his second consecutive, term. Fernández and the PLD are credited with a number of initiatives that have moved the country forward technologically, with the completion in 2008 of the Metro Railway ("El Metro") in the Dominican Republic.

Foreign relations

The Dominican Republic maintains close relations with the nations of the Western Hemisphere and the principal nations of Europe. Relations with the U.S. are very close.[40]

The country is a member of the following international organizations:[2] ACP, Caricom (observer), ECLAC, FAO, G-77, IADB, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICC, ICCt, ICRM, IDA (graduate), IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, IHO (suspended), ILO, IMF, IMO, Intelsat (or ITSO), Interpol, IOC, IOM, IPU, ISO (correspondent member), ITU, ITUC, LAES, LAIA (observer), MIGA, NAM, OAS, OPANAL, OPCW (signatory), PCA, Rio Group, UN, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNIDO, Unión Latina, UNOCI, UNWTO (or WToO), UPU, WCO, WFTU, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WTO (or WTrO).

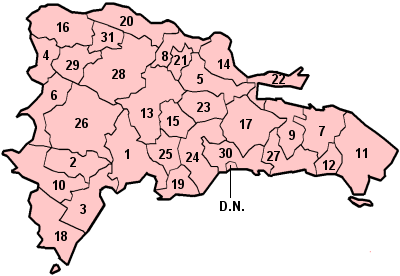

Provinces and municipalities

The Dominican Republic is divided into 31 provinces. Additionally, the national capital, Santo Domingo, is contained within its own Distrito Nacional (National District).

The provinces are divided into municipalities (municipios; singular municipio). They are the second–level political and administrative subdivisions of the country.

* The national capital, also known as Distrito Nacional (D.N.), is the city of Santo Domingo.

Geography

The Dominican Republic is situated on the eastern part of the second-largest island in the Greater Antilles, Hispaniola. The Dominican Republic shares the island roughly at a 2:1 ratio with Haiti. The whole country measures an area of 48,730 km² (or 48,921 km²),[41] making it the second largest country in the Antilles, after Cuba.[2] The country's capital and greatest metropolitan area, Santo Domingo, is located on the southern coast.

To the north, at a distance between 100 and 200 km, are three extensive, largely submerged banks, which geographically are a southeast continuation of the Bahamas: Navidad Bank, Silver Bank and Mouchoir Bank. Navidad Bank and Silver Bank have been officially claimed by the Dominican Republic.

The country's mainland has four important mountain ranges. The most northerly of these ranges is the Cordillera Septentrional ("Northern Mountain Range"), which extends from the northwestern coastal town of Monte Cristi, near the Haitian border, to the Samaná Peninsula in the east, running parallel to the Atlantic coast. The highest range in the Dominican Republic — indeed, in the whole of the West Indies — is the Cordillera Central ("Central Mountain Range") (in Haiti known as the Massif du Nord). It gradually bends southwards and finishes near the town of Azua de Compostela on the Caribbean coast. The Cordillera Central is home to the four highest peaks in the West Indies: Pico Duarte (3,098 m / 10,164 ft above sea level), La Pelona (3,094m), La Rucilla (3,049m) and Pico Yaque (2,760m).

In the southwest corner of the country, south of the Cordillera Central, there are two other ranges. The more northerly of the two is the Sierra de Neiba, while in the south the Sierra de Bahoruco is a continuation of the Massif de la Selle in Haiti.

There are other minor mountain ranges, such as the Cordillera Oriental ("Eastern Mountain Range"), Sierra Martín García, Sierra de Yamasá and Sierra de Samaná.

With mountain ranges running parallel to each other, the Dominican Republic boasts a number of valleys and plains. In between the Central and Septentrional mountain ranges lies the rich and fertile Cibao valley. This major valley is home to the city of Santiago de los Caballeros and to most of the farming areas in the nation. Rather less productive is the semi-arid San Juan Valley, south of the Cordillera Central and extending westward into Haiti. Still more arid is the Neiba Valley, tucked between the Sierra de Neiba and the Sierra de Bahoruco. This valley is also known in Haiti as the Cul-de-Sac. Much of the land in the Enriquillo Basin is below sea level, with a hot, arid, desert-like environment. There are other smaller valleys in the mountains such as the Constanza, Jarabacoa, Villa Altagracia and Bonao valleys.

There are many small offshore islands and cays that are part of the Dominican territory. The two largest islands near shore are Saona in the southeast and Beata in the southwest.

The Llano Costero del Caribe ("Caribbean Coastal Plain") is the largest of the plains in the Dominican Republic. Stretching north and east of Santo Domingo, it contains many sugar plantations in the savannahs that are common here. West of Santo Domingo its width is reduced to 10 km as it hugs the coast, finishing at the mouth of the Ocoa River. Another large plain is the Plena de Azua ("Azua Plain"), a very dry region in the Azua Province.

A few other small coastal plains are in the northern coast and in the Pedernales Peninsula.

Four major rivers drain the numerous mountains of the Dominican Republic. The Yaque del Norte carries excess water down from the Cibao Valley and empties into Monte Cristi Bay. Likewise, the Yuna River serves the Vega Real and empties into Samaná Bay. Drainage of the San Juan Valley is provided by the San Juan River, tributary of the Yaque del Sur, which empties into the Caribbean. The Artibonito is the longest river of Hispaniola and flows into Haiti. The Yaque del Norte is the longest and most important Dominican river.

There are many lakes and coastal lagoons; the largest lake is Lago Enriquillo, a saline lake at 40 m below sea level, the lowest point in the West Indies. Other important lakes are Laguna de Rincón or Cabral, with freshwater, and Laguna de Oviedo, a lagoon with brackish water.

Climate

The country is a tropical, maritime nation. Wet season is from May to November, and periodic hurricanes between June and November. Most rain falls in the northern and eastern regions. The average rainfall is 1346 mm, with extremes of 2500 mm in the northeast and 500 mm in the west. The main annual temperature ranges from 21 °C in the mountainous regions to 25 °C on the plains and the coast. The average temperature in Santo Domingo in January is 25 °C and 30 °C in July. Nonetheless, the highest mountaintops are covered in pine forests and have temperatures that can go several degrees below freezing during winter nights.

Environmental issues

Bajos de Haina, 12 miles (19 km) west of Santo Domingo, was included on the Blacksmith Institute's list of the world's 10 most polluted places, released in October 2006, due to lead poisoning by a battery recycling smelter closed in 1999. As the site never was cleaned up, children continue to be born with high lead levels causing learning disabilities, impaired physical growth and kidney damage.[42][43]

Symbols

Some of the important symbols include the flag of the Dominican Republic, the coat of arms, and the national anthem, titled Himno Nacional. The flag has a large white cross that divides it into four quarters. Two quarters are red and two are blue. Red represents the blood shed by the liberators. Blue expresses God's protection over the nation. The white cross symbolizes the struggle of the liberators to bequeath future generations a free nation. An alternate interpretation is that blue represents the ideals of progress and liberty, whereas white symbolizes peace and union amongst Dominicans.[44] In the center of the cross is the Dominican coat of arms, in the same colors as the national flag.

The national flower is the flower of the West Indies Mahogany[45] The national bird is the Cigua Palmera or Palmchat.[46]

Economy

Recent years

The Dominican Republic is a lower middle-income[47] developing country primarily dependent on natural resources and government services. Although the service sector has recently overtaken agriculture as the leading employer of Dominicans (due principally to growth in tourism and Free Trade Zones), agriculture remains the most important sector in terms of domestic consumption and is in second place, behind mining, in terms of export earnings. Real estate tourism alone accounted for $1.5 billion in annual earnings.[48] Free Trade Zone earnings and tourism are the fastest-growing export sectors. Remittances ("remesas") from Dominicans living abroad are estimated to be more than $2 billion dollars per year.

Following economic turmoil in the late 1980s and 1990, during which the gross domestic product (GDP) fell by up to 5% and consumer price inflation reached an unprecedented 100%, the Dominican Republic entered a period of moderate growth and declining inflation until 2002, after which the economy entered a recession. This recession followed the collapse of the second-largest commercial bank of the country (Baninter), linked to a major incident of fraud valued at $3.5 billion during the administration of President Hipolito Mejia (2000-2004). The Baninter fraud had a devastating effect on the Dominican economy, with GDP dropping by 1% in 2003 while inflation ballooned by over 27%.

Despite a widening merchandise trade deficit, tourism earnings and remittances have helped build foreign exchange reserves. The Dominican Republic is current on foreign private debt, and has agreed to pay arrears of about $130 million to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Commodity Credit Corporation.

According to the 2005 Annual Report of the United Nations Subcommittee on Human Development in the Dominican Republic, the country is ranked #71 in the world for resource availability, # 79 for human development, and #14 in the world for resource mismanagement. These statistics emphasize national government corruption, foreign economic interference in the country, and the rift between the rich and poor.

The Dominican Republic has become a trans-shipment point for South American drugs to Europe as well as the United States and Canada.[2] Money laundering is favored by Colombian drug cartels via the Dominican Republic for the ease of illicit financial transactions.[2]

The Dominican Republic enjoys a growing economy and a 2007 GDP per capita of $9,208, in PPP terms, which is relatively high in Latin America. In the trimester of January - March 2007 it experienced an exceptional growth of 9.1% in its GDP, below the previous year's 10.9% in the same period. Growth was led by imports, followed by exports, with finance and foreign investment the next largest factors.[49] The service sector in general has experienced growth in recent years, as has construction. Economic growth takes place in spite of a chronic energy shortage,[50] which causes frequent blackouts and very high prices.

Santo Domingo, the capital of the Republic is the source of most of is GDP and has become one of the leading cities of the Caribbean. The biggest tourist center in the country is the region of Puerto Plata.

Currency

The Dominican peso (DOP) is the national currency of the country, although US dollars (USD) are accepted at most tourist sites. The peso was worth the same as the USD until the 1980s, but has depreciated. The exchange rate in 1993 was 14.00 pesos per USD and 16.00 pesos in 2000, but it jumped to 53.00 pesos per USD in 2003. In 2004, the exchange rate was back down to around 31.00 pesos per USD.

The U.S. dollar is implicated in almost all commercial transactions of the Dominican Republic; such dollarization is common in high inflation economies. On February 2005, 1.32 USD = one € = 29 DR pesos; in October 2005, 1.19 USD = one € = 32 DR pesos. As of September 2007 the value of the peso is 1 USD=0.7006 EUR=33.430 DOP.[51][52]

Tourism

Tourism is fueling the Dominican Republic's economic growth. For example, the contribution of travel and tourism to employment is expected to rise from 550,000 jobs in 2008 — 14.4% of total employment or 1 in every 6.9 jobs — to 743,000 jobs — 14.2% of total employment or 1 in every 7.1 jobs by 2018.[53]

Demographics

Population

The population of Dominican Republic in 2007 was estimated by the United Nations at 9,760,000,[54] which placed it as number 82 in population among the 193 nations of the world. In that year approximately 5% of the population was over 65 years of age, with another 35% of the population under 15 years of age. There were 103 males for every 100 females in the country in 2007.[2] According to the UN, the annual population growth rate for 2006–2007 is 1.5%, with the projected population for the year 2015 at 10,121,000.

It was estimated by the Dominican government that the population density in 2007 was 192 per km² (498 per sq mi), and 63% of the population lived in urban areas.[55] The southern coastal plains and the Cibao Valley are the most densely populated areas of the country. The capital city, Santo Domingo, had a population of 3.0 million in 2007. Other important cities are Santiago de los Caballeros, La Romana, San Pedro de Macorís, San Francisco de Macorís, San Felipe de Puerto Plata, and Concepción de la Vega. According to the United Nations, the urban population growth rate for 2000–2005 was 2.3%.[56]

Ethnic composition

According to the CIA World Fact Book, the ethnic composition of the Dominican population is 73% mixed race, 16% white and 11% black.[2] The mixed population is a racial mixture of either White, Black or Taino heritage. [12] Other ethnic groups in the Dominican Republic include Haitians, Germans, Italians, French, Jews, Spaniards, and Americans. A smaller presence of East Asians (primarily ethnic Chinese and Japanese) and Middle Easterners (primarily Lebanese) can be found throughout the population.

Racial issues

As elsewhere in the Spanish Empire, the original Spanish colony of Hispaniola employed a social system known as casta, wherein Peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain) occupied the highest echelon. These were followed, in descending order of status, by: criollos, castizos, mestizos, mulattoes, Indians, zambos, and lastly, black slaves.[57][58] The stigma of these social strata persisted for many years, reaching its culmination in the Trujillo regime, as the dictator used racial persecution and nationalistic fervor against Haitians.[59][32]

According to a study by the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute, about 90% of the contemporary Dominican population has some African and taino ancestry.[60] Most Dominicans self-identify as being of mixed-race rather than black in contrast to African identity movements in the United States. A variety of terms are used to represent a range of skintones depending on ancestry such as "morena" (brown), "canela" (red/brown), "india" (Indian), "blanca oscura" (dark white), and "trigueño" (wheat colored),[61] among others.

Many have claimed that this represents a reluctance to self-identify with African descent and the culture of the freed slaves. According to Dr. Miguel Anibal Perdomo, professor of Dominican Identity and Literature at Hunter College in New York City, "There was a sense of 'deculturación' among the African slaves of Hispaniola. [There was] an attempt to erase any vestiges of African culture from the Dominican Republic. We were, in some way, brainwashed and we've become westernized."[62]

However, this view is not universal, as many also claim that Dominican culture is simply different and rejects the racial categorizations of other regions. Ramona Hernández, director of the Dominican Studies Institute at City College of New York asserts that the terms were originally an act of defiance in a time when being mulatto was stigmatized. "During the Trujillo regime, people who were dark skinned were rejected, so they created their own mechanism to fight it." She went on to explain, "When you ask, 'What are you?' they don't give you the answer you want ... saying we don't want to deal with our blackness is simply what you want to hear."[63] The Dominican Republic is not unique in this respect either. In a 1976 census survey conducted in Brazil, respondents described their skin color in 136 distinct terms.[63][64]

Religion

More than 95% of the population adheres to Christianity, mostly Roman Catholicism, followed by a growing contingent of Protestant groups such as Seventh-day Adventist, and Jehovah's Witnesses. Recent but small scale immigration has brought other religions, which make up small percentages of the population: Spiritist: 2.18%, Mormons: 1.0%, Buddhist: 0.10%, Bahá'í: 0.07%, Muslim: 0.02%, and Jewish: 0.01%.[65]

Roman Catholicism was introduced by Columbus and Spanish missionaries. Religion wasn’t really the foundation of their entire society, as it was in other parts of the world at the time, and most of the population didn’t attend church on a regular basis. Nonetheless, most of the education in the country was based upon the Catholic religion, as the Bible was required in the curriculum in all public schools. Children would use religious based dialogue when greeting a relative or parent. For example: a child would say “Bless me, mother”, and the mother would reply “May God bless you”. Most Dominicans are Roman Catholic.

The nation has two patroness saints: Nuestra Señora de la Altagracia (Our Lady Of High Grace) is the patroness of the Dominican people, and Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes (Our Lady Of Mercy) is the patroness of the Dominican Republic.

Eventually the Catholic Church began to lose popularity in the late 1800s. This was due to a lack of funding, priests, and support programs. Because of this the Protestant evangelical movement began to gain support. Protestants emphasized biblical teachings like the Catholics, but also practiced rejuvenation and economic independence. The Protestants added diversity to the Dominican Republic, and there was almost no religious conflict with the Catholics.

There has always been religious freedom throughout the entire country. It wasn’t until the 1950s that restrictions were placed upon churches by Trujillo. Letters of protest were sent against the mass arrests of government adversaries. Trujillo began a campaign against the church and planned to arrest priests and bishops who preached against the government. This campaign ended before it was even put into place, with his assassination.

Judaism appeared in the Dominican Republic in the late 1930s. During World War Two, a group of Jews escaping Nazi Germany fled to the Dominican Republic and founded the city of Sosua. It has remained the center of the Jewish population since.[66]

Education

Primary education is officially free and compulsory for children between the ages of 7 and 14, although those who live in isolated areas have limited access to schooling. Primary schooling is followed by a two-year intermediate school and a four-year secondary course, after which a diploma called the bachillerato (high school diploma) is awarded. Relatively few lower-income students succeed in reaching this level due to financial hardships and limitation due to location. Most wealthier students choose to attend private schools, which are frequently sponsored by religious institutions. Some public and private vocational education is available, particularly in the field of agriculture, but this too reaches only a tiny percentage of the population.[67]

Health statistics

In 2007 the Dominican Republic had a birth rate of 22.91 per 1000, and a death rate of 5.32 per 1000.[2] Dengue and malaria are endemic to the country.[68] There is currently a mission based in the United States to combat the AIDS rate in the Dominican Republic.[69]

Immigration

During the Haitian rule over the whole island of Hispaniola (1822-1844), former black slaves and escapees from the United States were invited by the Haitian government to settle there.[citation needed] In the late 1800s and early 1900s, large groups immigrated to the country from Venezuela and Puerto Rico, so much so that two of the country's former presidents and life-long political rivals, Juan Bosch[70] and Joaquín Balaguer[71][72] both had Puerto Rican parents. During the first decades of the 20th century, many Arabs, primarily from Lebanon, settled in the country. There is also a sizable Indian and Chinese population. The town of Sosúa has many Jews who settled there during World War II.[73]

In recent decades, immigration from Haiti has increased once again. Most Haitian immigrants arrive in the Dominican Republic illegally and work at low-paying, unskilled labor jobs, including construction work, household cleaning, and in sugar plantations.[74] Current estimates put the Haitian-born population in the Dominican Republic as high as 1 million.[75] Working conditions on these sugar plantations have caused controversy, including assertions that conditions are near-slavery.[76] Moreover, the children of illegal Haitian immigrants are denied citizenship[74][77] and basic health care,[78] and there are frequent physical attacks and roundups on adult immigrants.[79]

Some Dominican and Haitian officials deny such accusations of slavery, with the Haitian ambassador Fritz Cineas stating, "I still have not received any complaint of violation of human rights against the Haitian immigrants in the country."[80] However, the President of the Dominican Republic, Leonel Fernández, stated publicly during a seminar on immigration policy in 2005 that collective expulsions of Haitians were carried out "in an abusive and inhuman way."[81] Selective enforcement of deportation rules is much criticized in Haiti, and it has been said that "the Dominicans could help heal many of Haiti's open political wounds by extraditing back to Haiti many of the criminals of the 1991 coup d'état and the Duvalier dictatorship who enjoy de facto political asylum in the Dominican Republic." These people enjoy de facto political asylum in the Dominican Republic, critics say.[82] When asked for a response for the current situation, Fernandez stated, "There must exist an extradition treaty between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, but there isn't one between our two countries."[82]

"Stateless" Haitians

Haiti, with nearly as many people but with half the land size, is much poorer than the Dominican Republic. In 2002 less than half of the Haitian population had formal jobs; in 2003 nearly half of the Haitian population was illiterate, and 80% of all Haitians were poor.[83] Facing stark prospects for survival, many Haitians cross the border to Dominican soil without authorization in search of better living conditions. But, as is usual for illegal immigrants in nearly all nations, they are relegated to working class status, largely in farming, often sugar cane plantations, and house construction[84] with poor housing and poor schools for their children. Although any person born on Dominican soil is a Dominican citizen, per the Dominican constitution, and any legally residing person in the Dominican Republic can theoretically become a citizen, many Dominican-born children of Haitian ethnicity are stateless, as their parents are denied Dominican citizenship because they are deemed to be transient or have an illegal or undocumented residency status, or are unable to obtain Haitian citizenship for lack of proper documents or witnesses:[85] note that Haiti's Constitution states in Title II, Article 11 that "Any person born of a Haitian father or Haitian mother who are themselves native-born Haitians and have never renounced their nationality possesses Haitian nationality at the time of birth".[86]

A large number of Haitian women cross the border to Dominican soil during their last weeks of pregnancy to obtain much-needed medical attention for childbirth, often arriving with several health problems, since Dominican public hospitals don't refuse medical services based on nationality or legal status. Statistics from a hospital in Santo Domingo report that over 22% of childbirths are by Haitian mothers.[87]

Competition for jobs has led to the deportation of many Haitians in an effort to save native Dominican rights.

Unofficially there are 800,000 illegal Haitians (other estimates place this figure around 1.2 million) living in the Dominican Republic, which accounts for a little over 10% of the national population.[88] After a UN delegation issued a preliminary report stating that it found a profound problem of racism and discrimination against people of Haitian origins, Dominican Foreign Minister Carlos Morales Troncoso issued a formal statement denouncing it and asserting that "Our border with Haiti has its problems, this is our reality and it must be understood. It is important not to confuse national sovereignty with indifference, and not to confuse security with xenophobia..."[89]

Emigration

The Dominican Republic has experienced three distinct waves of emigration in the second half of the twentieth century. The first period began in 1961, when a coalition of high-ranking Dominicans, with assistance from the CIA, assassinated General Rafael Trujillo, the nation's military dictator.[90] In the wake of his death, fear of retaliation by Trujillo's allies, and political uncertainty in general, spurred migration from the island. In 1965, the United States began a military occupation of the Dominican Republic and eased travel restrictions, making it easier for Dominicans to obtain American visas.[91] From 1966 to 1978, the exodus continued, fueled by high unemployment and political repression. Communities established by the first wave of immigrants to the U.S. created a network that assisted subsequent arrivals. In the early 1980s, underemployment, inflation, and the rise in value of the dollar all contributed to a third wave of migration from the island nation. Today, emigration from the Dominican Republic remains high, facilitated by the social networks of now-established Dominican communities in the United States.[92]

Crime

The Dominican Republic has served as a transportation hub for Colombian drug cartels.[93][2] In 2004 it was estimated that 8% of all cocaine smuggled into the United States has come through the Dominican Republic.[94] The Dominican Republic responded with increased efforts to seize drug shipments, arrest and extradite those involved, and combat money-laundering. A 1995 report stated that social pressures and increasing poverty — which was then increasing — have led to a rise in prostitution within the Dominican Republic. Though prostitution is legal within the country and the age of consent is 18, child prostitution is a growing phenomenon in impoverished areas. In an environment where young girls are often denied employment opportunities offered to boys, prostitution frequently becomes a source of supplementary income[citation needed]. UNICEF estimated in 1994 that at least 25,000 children were involved in the Dominican sex trade, 63% of that figure being girls.[95]

Culture

The culture of the Dominican Republic, like its Caribbean neighbors, is a blend of the European colonists, Taínos and Africans, and their cultural legacies. Spanish, also known as Castellano (Castilian) is the official language. Other languages such as Haitian Creole, English, French, German, and Italian are also spoken to varying degrees. Haitian Creole is spoken fluently by 159,000[96] or as many as 1.2 million[97] Haitian nationals and Dominicans of Haitian descent, and is the third most spoken language after Spanish and English. European, African and Taíno cultural elements are most prominent in food, family structure, religion and music. Many Arawak/Taíno names and words are used in daily conversation and for many items endemic to the DR.[2]

Cuisine

Dominican Republic cuisine is predominantly made up of a combination of Spanish, Taino and African influences over the last few centuries. Typical cuisine is quite similar to what can be found in other Latin American countries but, many of the names of dishes are different. Breakfast usually consists of eggs and mangú (mashed, boiled plantain). For heartier versions, these are accompanied by deep-fried meat(typically Dominican salami) and/or cheese. Similar to Spain, lunch is generally the largest and most important meal of the day. Lunch usually consists of some type of meat (chicken, pork or fish), rice and beans, and a side portion of salad. "La Bandera" (literally, The Flag), the most popular lunch dish, consists of broiled chicken, white rice and red beans.

Typical Dominican cuisine usually accommodates all four food groups, incorporating meat or seafood; rice, potatoes or plantains; and is accompanied by some other type of vegetable or salad. However, meals usually heavily favor meats and starches, less dairy products, and little to no vegetables. Many dishes are made with sofrito, which is a mix of local herbs and spices sautéed to bring out all of the dish's flavors. Throughout the south-central coast, bulgur, or whole wheat, is a main ingredient in quipes or tipili (bulgur salad). Other favorite Dominican dishes include chicharrón, yucca, casave, and pastelitos (empanadas), batata, pasteles en hoja, chimichurris, platanos maduros and tostones.

Some treats Dominicans enjoy are arroz con dulce (or arroz con leche), bizcocho dominicano (lit. Dominican cake), habichuelas con dulce (sweet creamed beans), flan, frío frío (snow cones), dulce de leche, and caña (sugarcane).

The beverages Dominicans enjoy include Morir Soñando, rum, beer, Mama Juana, batida (smoothie), ponche, mabí, and coffee.[98]

Music

Musically, the Dominican Republic is known for the creation of Merengue music,[99] a type of lively, fast-paced rhythm and dance music consisting of a tempo of about 120 to 160 beats per minute (it varies wildly) based on musical elements like drums, brass, and chorded instruments, as well as some elements unique to the music style of the DR, such as the marimba. Its syncopated beats use Latin percussion, brass instruments, bass, and piano or keyboard. Not known for social content in its commercial form (Merengue Típico or Perico Ripiao is very socially charged), it is primarily a dancehall music that was declared the national music during the Trujillo regime. Well-known merengue singers include Juan Luis Guerra, Fernando Villalona, Eddy Herrera, Sergio Vargas, Toño Rosario, Johnny Ventura, and Milly Quezada. Merengue became popular mostly on the east coast of the United States during the 1980s and 90s,[100] when many Puerto Rican groups such as Elvis Crespo were produced by Dominican bandleaders and writers living in the US territory[citation needed]. The emergence of Bachata-Merengue along with a larger number of Dominicans living among other Latino groups (particularly Cubans and Puerto Ricans in New York, New Jersey, and Florida) contributed to the music's growth in popularity.[101]

Bachata, a form of music and dance that originated in the countryside and rural marginal neighborhoods of the Dominican Republic, has become quite popular in recent years. Its subjects are often romantic; especially prevalent are tales of heartbreak and sadness. In fact, the original term used to name the genre was "amargue" ("bitterness," or "bitter music"), until the rather ambiguous (and mood-neutral) term bachata became popular. Bachata grew out of, and is still closely related to, the pan-Latin American romantic style called bolero. Over time, it has been influenced by merengue and by a variety of Latin American guitar styles.

Another genre of music that has been growing in popularity in recent years in the Dominican Republic is Dominican Rap, or "Rap del Patio" (Street Rap). This genre can be described as similar to American Hip Hop or Rap music rapped in Spanish with a thick Dominican accent, with subject matter that varies from social problems to money to fame, similarly to its U.S. counterpart. It must be noted, however, that it differs from Reggaeton in the fact that the beats do not use the familiar Dem Bow rhythm of Reggaeton, instead using beats similar to American rap. Singing is usually not a part of Rap del Patio; and the themes of Rap del Patio are usually more street-oriented rather than the club-themed Reggaeton. Notable artists are Lapiz Conciente, R-1, Vakero, Joa and Toxic Crow.

Sports

Baseball is by far the most popular sport in the Dominican Republic today.[102] After the United States, the Dominican Republic has the second-highest number of baseball players in Major League Baseball (MLB). Some of the Dominican players have been regarded as among the best in the game. Following are a few players born in the Dominican Republic:

- Carlos Peña, first baseman for the Tampa Bay Rays

- Sammy Sosa, 1998 National League MVP Award winner and member of the exclusive (only 5 other players have reached the mark) 600 home run club

- Carlos Villanueva, pitcher for the Milwaukee Brewers

- Albert Pujols, 2001 National League Rookie of the Year (2005) and National League MVP Award winner

- Pedro Martínez, three–time Cy Young Award winner and considered one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history

- Vladimir Guerrero, 2004 American League MVP Award winner and 2007 Home Run Derby winner

- David Ortiz, first baseman and designated hitter for the Boston Red Sox

- José Reyes, 2007 MLB Stolen Base Leader

- Manny Ramírez, outfielder for the Boston Red Sox

- Miguel Tejada, shortstop for the Houston Astros

- Alfonso Soriano, infielder/outfielder for the Chicago Cubs

- Héctor Luna, infielder for the Toronto Blue Jays

- Robinson Canó, second baseman for the New York Yankees

- Melky Cabrera, center fielder for the New York Yankees

- Hanley Ramírez, shortstop for the Florida Marlins, and considered one of the best all-around players in baseball.

Historically, the Dominican Republic has been linked to MLB since Ozzie Virgil, Sr. became the first Dominican to play there. Other very notable players were Juan Marichal, Felipe Alou, Rico Carty, George Bell, Jose Rijo and Stan Javier, among many others.

The Dominican Republic also has its own baseball league, the Dominican Winter Baseball League, which runs its season from October to January. It comprises six teams: Águilas Cibaeñas (Cibao Eagles), Azucareros del Este (Eastern Sugar-makers), Estrellas Orientales (Eastern Stars), Gigantes del Cibao (Cibao Giants), Leones del Escogido (Escogido Lions), and Tigres del Licey (Licey Tigers). Many MLB and minor league players play in the Dominican League during their own off-season. As such, the Dominican Winter League serves as an important "training ground" for these leagues.

The Dominican Republic has participated in the Baseball World Cup, winning one Gold (1948), three Silver (1942, 1950, 1952), and two Bronze (1943, 1969), placing it seventh, right after Puerto Rico's one Gold, four Silver, and four Bronze. (Cuba holds a record twenty-five Gold, two Silver and two Bronze.)

The country also participated in the 2006 World Baseball Classic, the inaugural tournament, in which they finished semi–finalists along with Korea.

Olympic gold medalist and world champion over 400 m hurdles Félix Sánchez hails from the Dominican Republic, as does current defensive end for the San Diego Chargers (National Football League [NFL]), Luis Castillo. Castillo was the cover athlete for the Spanish language version of Madden NFL 08.[103]

The National Basketball Association (NBA), also has players from the Dominican Republic, such as:

- Francisco García, guard–forward for the Sacramento Kings; first round pick in the 2005 NBA Draft

- Al Horford, power forward, third overall pick by the Atlanta Hawks in the 2007 NBA Draft

- Felipe López, former shooting guard for several teams

Boxing is one of the more important sports after baseball, and the country has produced scores of world-class fighters and world champions, among them Carlos Teo Cruz, Leo Cruz, Julio César Green, Joan Guzmán, and Juan Carlos Payano.

Holidays

| Date | Name | |

|---|---|---|

| January 1 | New Year's Day | Non-working day. |

| January 6 | Catholic day of the Epiphany | Movable. |

| January 21 | Virgen de la Altagracia | Non-working day. Patroness Day (Catholic). |

| January 26 | Duarte's day | Movable. Founding Father. |

| February 27 | Independence Day | Non-working day. National Day. |

| (Variable date) | Holy Week | Working days, except Good Friday. A Catholic holiday. |

| May 1 | Labour Day | Movable. |

| (Variable date) | Catholic Corpus Christi | Non-working day. A Thursday in May or June (60 days after Easter Sunday). |

| August 16 | Restoration Day | Non-working day. |

| September 24 | Virgen de las Mercedes | Non-working day. A Patroness Day (Catholic) |

| November 6 | Constitution Day | Movable. |

| December 25 | Christmas Day | Non-working day. Birth of Jesus Christ |

Notes:

- Non-working holidays are not moved to another day.

- If a movable holiday falls on Saturday, Sunday or Monday then it is not moved to another day. If it falls on Tuesday or Wednesday, the holiday is moved to the previous Monday. It falls on Thursday or Friday, the holiday is moved to the next Monday.

Military

Congress authorizes a combined military force of 44,000 active duty personnel. Actual active duty strength is approximately 32,000. However, approximately 50% of those are used for non-military activities such as security providers for government-owned non-military facilities, highway toll stations, prisons, forestry work, state enterprises, and private businesses. The Commander in Chief of the military is the President. The principal missions are to defend the nation and protect the territorial integrity of the country. The army, larger than the other services combined with approximately 20,000 active duty personnel, consists of six infantry brigades, a combat support brigade, and a combat service support brigade. The air force operates two main bases, one in the southern region near Santo Domingo and one in the northern region near Puerto Plata. The navy operates two major naval bases, one in Santo Domingo and one in Las Calderas on the southwestern coast, and maintains 12 operational vessels. In the Caribbean, only Cuba has a larger military force.

The armed forces have organized a Specialized Airport Security Corps (CESA) and a Specialized Port Security Corps (CESEP) to meet international security needs in these areas. The Secretary of the Armed Forces has also announced plans to form a specialized border corps (CESEF). Additionally, the armed forces provide 75% of personnel to the National Investigations Directorate (DNI) and the Counter-Drug Directorate (DNCD).

The Dominican National Police force contains 32,000 agents. The police are not part of the Dominican armed forces, but share some overlapping security functions. Sixty-three percent of the force serve in areas outside traditional police functions, similar to the situation of their military counterparts.[40]

Services and transportation

There are two transportation services in the Dominican Republic, one controlled by the government through the Oficina Técnica de Transito Terrestre (O.T.T.T.) and the Oficina Metropolitana de Servicios de Autobuses (OMSA), and the other controlled by private business, among them, Federación Nacional de Transporte La Nueva Opción (FENATRANO) and the Confederacion Nacional de Transporte (CONATRA).

The government transportation system covers large routes in metropolitan areas, such as Santo Domingo and Santiago, for very inexpensive prices. In December 2006, the price was DOP$5.00(US$0.15), and air-conditioned bus rides were priced at DOP$10 (US$0.30). It should be noted that most OMSA buses are currently in very poor condition, and OMSA has been criticized for its incapability to fully meet the people's needs.[104]

FENATRANO and CONATRA offer their services with voladoras (vans) or conchos (cars), which have routes in most parts of the cities. These cars have roofs painted in yellow or green in order to identify them. The cars have scheduled days to work, depending on the color of the roof, and have been described as unsafe.[105]

Communications

The Dominican Republic has a well developed telecommunications infrastructure, with extensive mobile phone services and landline services. The telecommunications regulator in the country is INDOTEL, Instituto Dominicano De Telecomunicaciones. The Dominican Republic offers cable internet and DSL in most parts of the country, and many ISPs provide 3G wireless internet service. Projects to extend Wi-Fi hot spots have been made in Santo Domingo. As of October 2007 a new service was introduced in the country via WiMax, by OneMax, Tricom, and the former Codetel, now Claro, that provides telephony over IP as well as nation-wide broadband services to both residential and commercial users. In fact the DR is the only country in all Latin America to have this kind of service up to this date at a national level.

Numerous television channels are available, including digital cable Telecable Nacional and Aster. Many other companies provide digital television services with channels from Latin America and the world. The reported speeds are from 256 kbit/s /128 kbit/s for residential services and up to 4 MB / 2 MB for commercial and residential service. (Each set of numbers denotes downstream/upstream speed.)

The Dominican Republic's commercial radio stations are in the process of transferring to the digital spectrum via HD Radio.

As of October 2007, there are five major communication companies: CODETEL, Orange, TRICOM, Trilogy Dominicana and Onemax.

On February 1, 2007, Verizon changed the names of its wireless services to Claro and CODETEL. The company has been owned since 2006 by Carlos Slim Helú's América Móvil. Claro is now the official name of the Wireless Division and CODETEL (the original Compañia Dominicana de Teléfonos) is the updated name for the Verizon Dominicana landline and broadband market.

Highways

The Dominican Republic has five major highways, which take travelers to every important town in the country. The three major highways are Autopista Duarte, Autopista del Este, and Autopista del Sur, which go to the north, east, and western side of the country. Dominican Republic lacks a good system of routes interconnecting small towns, and most of these routes are unpaved and are getting improved.

Ports

The Port of Santo Domingo, with its location at the center of the Caribbean is well suited for flexible itinerary planning and has excellent support, road and airport infrastructure within the Santo Domingo region, which facilitate access and transfers. The port is suitable for both turnaround and transit calls.

Electricity

Electrical services in the country have been a headache for the population, as well as the business and other areas for more than 40 years. Due to the extreme corruption within the government, no administration has been able to cope with this problem. In 1998, three regional electricity distribution systems were privatized via sale of 50% of shares to foreign operators; in an unexpected decision, the Mejía administration repurchased all foreign-owned shares in two of these systems in late 2003. The third, serving the eastern provinces, is operated by U.S. concerns and is 50% U.S.-owned. Industry experts estimated distribution losses for 2006 surpassed 40%, primarily due to low collection rates, theft, and corruption. At the close of 2006, the government had exceeded its budget for electricity subsidies, spending close to U.S. $650 million.[106]

Household and general electrical service is delivered at 110 volts alternating at 60 Hz; electrically-powered items from the United States work with no modifications. The majority of the country has access to electricity. Still, in 2007 some areas have outages lasting as long as 20 hours a day. Tourist areas tend to have more reliable power, as do business, travel, healthcare, and vital infrastructure. The situation improved in 2006, with 200 circuits (40% of the total) providing permanent electricity, as 85% of electric demand overall was met and blackouts were reduced from 6.3 hours per day to 3.7.[107] Concentrated efforts were announced to increase efficiency of delivery to places where the collection rate reached 70%.[108] The electricity sector is highly politicized, and with 2008 presidential election campaigning already in motion the prospect of further effective reforms of the sector is poor. Debts, including government debt, amount to more than U.S. $500 million. Some generating companies are undercapitalized and at times unable to purchase adequate fuel supplies.[109]

See also

- Dominican National Team

- Foreign relations of the Dominican Republic

- Law of the Dominican Republic

- List of people from the Dominican Republic

- List of players from Dominican Republic in Major League Baseball

- List of universities in the Dominican Republic

- List of wettest known tropical cyclones in the Dominican Republic

- Military of the Dominican Republic

References

- ^ a b "Santo Domingo, city, Dominican Republic". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Bartleby.com. 2005. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "CIA- The World Factbook – Dominican Republic". CIA. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ Ramos, Ruth (2005). "Dominican Republic History". Visiting the Dominican Republic.com. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "ADN Mitocondrial Taino en la República Dominicana". Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- ^ "Taino Name for the Islands". Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e "Dominican Republic". Encarta Encyclopedia. Microsoft Corporation. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ a b Rawley, James A. (2005). The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History. University of Nebraska Press. p. 49. ISBN 0803239610.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lord, Lewis. "How Many People Were Here Before Columbus?". McGraw-Hill/Dushkin: PowerWeb Article. From U.S. News & World Report, August 18-25, 1997, pp. 68-70. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- ^ Keegan, William. "Death Toll". Millersville University, from Archaeology (January/February 1992, p. 55). Retrieved 2008=06-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Dominican Students At Yale - Home". Yale University; Dominican Student Association. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- ^ "The Story Of... Smallpox—and other Deadly Eurasian Germs". Retrieved 2008-06-19.