History of the telephone: Difference between revisions

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

[[File:Trådtelefon-illustration.png|thumb|right|200pcx|19th century'' 'tin can','' or'' 'lover's' ''telephone]] |

[[File:Trådtelefon-illustration.png|thumb|right|200pcx|19th century'' 'tin can','' or'' 'lover's' ''telephone]] |

||

Before the invention of electromagnetic telephones, there were mechanical |

Before the invention of electromagnetic telephones, there were mechanical devices for transmitting spoken words over a greater distance than that of normal speech. The very earliest mechanical telephones were based on sound transmission through pipes or other physical media. [[Speaking tube]]s long remained common, including a lengthy history of use aboard ships, and can still be found today. |

||

A different device, the [[tin can telephone]], or'' 'lover's phone','' has also been known for centuries. It connected two diaphragms with a taut string or wire which transmitted sound by mechanical vibrations from one to the other along the wire, and not by a [[Signal (electronics)|modulated electrical current]]. The classic example is the children's toy made by connecting the bottoms of two paper cups, metal cans, or plastic bottles with string. |

A different device, the [[tin can telephone]], or'' 'lover's phone','' has also been known for centuries. It connected two diaphragms with a taut string or wire which transmitted sound by mechanical vibrations from one to the other along the wire, and not by a [[Signal (electronics)|modulated electrical current]]. The classic example is the children's toy made by connecting the bottoms of two paper cups, metal cans, or plastic bottles with string. |

||

Revision as of 03:57, 28 August 2009

The history of the telephone chronicles the development of the electrical telephone, and includes a brief review of its earlier predecessors.

Telephone prehistory

Mechanical devices

Before the invention of electromagnetic telephones, there were mechanical devices for transmitting spoken words over a greater distance than that of normal speech. The very earliest mechanical telephones were based on sound transmission through pipes or other physical media. Speaking tubes long remained common, including a lengthy history of use aboard ships, and can still be found today.

A different device, the tin can telephone, or 'lover's phone', has also been known for centuries. It connected two diaphragms with a taut string or wire which transmitted sound by mechanical vibrations from one to the other along the wire, and not by a modulated electrical current. The classic example is the children's toy made by connecting the bottoms of two paper cups, metal cans, or plastic bottles with string.

Electrical devices

The telephone emerged from the creation of, and successive improvements to the electrical telegraph. In 1804 Catalan polymath and scientist Francisco Salvá i Campillo constructed an electrochemical telegraph.[1] An electromagnetic telegraph was created by Baron Schilling in 1832. Carl Friedrich Gauß and Wilhelm Weber built another electromagnetic telegraph in 1833 in Göttingen.

The first commercial electrical telegraph was constructed by Sir William Fothergill Cooke and entered use on the Great Western Railway in Britain. It ran for 13 miles from Paddington station to West Drayton and came into operation on April 9, 1839.

Another electrical telegraph was independently developed and patented in the United States in 1837 by Samuel Morse. His assistant, Alfred Vail, developed the Morse code signaling alphabet with Morse. America's first telegram was sent by Morse on January 6, 1838, across two miles of wiring.

During the second half of the 19th century inventors tried to find ways of sending multiple telegraph messages simultaneously over a single telegraph wire by using different modulated frequencies for each message. These inventors included Charles Bourseul, Thomas Edison, Elisha Gray, and Alexander Graham Bell. Their efforts to develop acoustic telegraphy in order to significantly reduce the cost of telegraph messages led directly to the invention of the telephone, or 'the speaking telegraph'.

Invention of the telephone

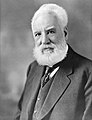

Credit for the invention of the electric telephone is frequently disputed, and new controversies over the issue have arisen from time-to-time. Charles Bourseul, Antonio Meucci, Johann Philipp Reis, Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray, amongst others, have all been credited with the telephone's invention. The early history of the telephone became and still remains a confusing morass of claims and counterclaims, which were not clarified by the huge mass of lawsuits that hoped to resolve the patent claims of many individuals and commercial competitors. The Bell and Edison patents, however, were forensically victorious and commercially decisive.

-

Antonio Meucci, 1854, constructed telephone-like devices.

-

Johann Philipp Reis, 1860, constructed prototype 'make-and-break' telephones, today called Reis' telephones.

-

Alexander Graham Bell was awarded the U.S. patent for the invention of the telephone in 1876.

-

Elisha Gray, 1876, designed a telephone prototype in Highland Park, Illinois.

-

Tivadar Puskás invented the telephone switchboard exchange in 1876.

Alexander Graham Bell has most often been credited as the inventor of the telephone. Additionally, the Italian-American inventor and businessman Antonio Meucci has been recognized by the U.S. Congress for his contributory work on the telephone. In Germany, Johann Philipp Reis is seen as a leading telephone pioneer who stopped only just short of a successful device. However, the modern telephone is the result of work done by many people, all worthy of recognition of their contributions to the field. Bell was, however, the first to patent the telephone, an "apparatus for transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically".

The Elisha Gray and Alexander Bell controversy considers the question of whether Bell and Gray invented the telephone independently and, if not, whether Bell stole the invention from Gray. This controversy is more narrow than the broader question of who deserves credit for inventing the telephone, for which there are several claimants.

The Canadian Parliamentary Motion on Alexander Graham Bell article reviews the controversial June 2002 United States congressional resolution recognizing Meucci's contributions 'in' the invention of the telephone (not 'for' the invention of the telephone), and the subsequent counter-motion unanimously passed in Canada's Parliament 10 days later which declared Bell its inventor. It examines critical aspects of both the parliamentary motion and the congressional resolution.

Early telephone developments

The following is a brief summary of the history of the development of the telephone:

- 1667: Robert Hooke invented a string telephone that conveyed sounds over an extended wire by mechanical vibrations.

- 1844: Innocenzo Manzetti first mooted the idea of a “speaking telegraph” (telephone).

- 1854: Charles Bourseul writes a memorandum on the principles of the telephone.(See the article : "Transmission électrique de la parole", L'Illustration, Paris, 26 August 1854).

- 1854: Antonio Meucci demonstrates an electric voice-operated device in New York; it is not clear what kind of device he demonstrated.

- 1861: Philipp Reis constructs the first speech-transmitting telephone

- 1872: Elisha Gray establishes Western Electric Manufacturing Company.

- July 1, 1875: Bell uses a bi-directional "gallows" telephone that was able to transmit "voicelike sounds", but not clear speech. Both the transmitter and the receiver were identical membrane electromagnet instruments.

- 1875: Thomas Edison experiments with acoustic telegraphy and in November builds an electro-dynamic receiver, but does not exploit it.

- 1875: Hungarian Tivadar Puskas (the inventor of telephone exchange) arrived in the USA.

- April 6, 1875: Bell's U.S. Patent 161,739 "Transmitters and Receivers for Electric Telegraphs" is granted. This uses multiple vibrating steel reeds in make-break circuits, and the concept of multiplexed frequencies.

- February 11, 1876: Elisha Gray designs a liquid transmitter for use with a telephone, but does not build one.

- March 7, 1876: Bell's U.S. patent No. 174,465 for the telephone is granted.

- March 10, 1876: Bell transmits the sentence: "Mr. Watson, come here! I want to see you!" using a liquid transmitter and an electromagnetic receiver.

- January 30, 1877: Bell's U.S. patent No. 186,787 is granted for an electromagnetic telephone using permanent magnets, iron diaphragms, and a call bell.

- April 27, 1877: Edison files for a patent on a carbon (graphite) transmitter. Patent No. 474,230 was granted on May 3, 1892, after a 15-year delay because of litigation. Edison was granted patent No. 222,390 for a carbon granules transmitter in 1879.

- 1877: First long-distance telephone line

- 1915: First U.S. coast-to-coast long-distance telephone call, ceremoniously inaugurated by A.G. Bell in New York City and his former assistant Thomas Augustus Watson in San Francisco, California.

Early commercial instruments

Early telephones were technically diverse. Some used liquid transmitters which soon went out of use. Some were dynamic: their diaphragms wriggled a coil of wire in the field of a permanent magnet or vice versa. This kind survived in small numbers through the 20th century in military and maritime applications where its ability to create its own electrical power was crucial. Most, however, used Edison/Berliner carbon transmitters, which were much louder than the other kinds, even though they required induction coils, actually acting as impedance matching transformers to make it compatible to the line impedance. The Edison patents kept the Bell monopoly viable into the 20th century, by which time telephone networks were more important than the instrument.

Early telephones were locally powered, using a dynamic transmitter or else powering the transmitter with a local battery. One of the jobs of outside plant personnel was to visit each telephone periodically to inspect the battery. During the 20th century, "common battery" operation came to dominate, powered by "talk battery" from the telephone exchange over the same wires that carried the voice signals. Late in the century, wireless handsets brought a revival of local battery power.

The earliest telephones had only one wire for both transmitting and receiving of audio, and used a ground return path, as was found in telegraph systems. The earliest dynamic telephones also had only one opening for sound, and the user alternately listened and spoke (rather, shouted) into the same hole. Sometimes the instruments were operated in pairs at each end, making conversation more convenient but also more expensive.

At first, the benefits of a switchboard exchange were not exploited. Instead, telephones were leased in pairs to the subscriber, for example one for his home and one for his shop, who must arrange with telegraph contractors to construct a line between them. Users who wanted the ability to speak to three or four different shops, suppliers etc would obtain and set up three or four pairs of telephones. Western Union, already using telegraph exchanges, quickly extended the principle to its telephones in New York City and San Francisco, and Bell was not slow in appreciating the potential.

Signalling began in an appropriately primitive manner. The user alerted the other end, or the exchange operator, by whistling into the transmitter. Exchange operation soon resulted in telephones being equipped with a bell, first operated over a second wire and later with the same wire using a condenser. Telephones connected to the earliest Strowger automatic exchanges had seven wires, one for the knife switch, one for each telegraph key, one for the bell, one for the push button and two for speaking.

Rural and other telephones that were not on a common battery exchange had a "magneto" or hand cranked generator to produce a high voltage alternating signal to ring the bells of other telephones on the line and to alert the exchange operator.

In 1877 and 1878, Edison invented and developed the carbon microphone used in all telephones along with the Bell receiver until the 1980s. After protracted patent litigation, a federal court ruled in 1892 that Edison and not Emile Berliner was the inventor of the carbon microphone. The carbon microphone was also used in radio broadcasting and public address work through the 1920s.

In the 1890s a new smaller style of telephone was introduced, packaged in three parts. The transmitter stood on a stand, known as a "candlestick" for its shape. When not in use, the receiver hung on a hook with a switch in it, known as a "switchhook." Previous telephones required the user to operate a separate switch to connect either the voice or the bell. With the new kind, the user was less likely to leave the phone "off the hook". In phones connected to magneto exchanges, the bell, induction coil, battery and magneto were in a separate bell box called a "ringer box." [2] In phones connected to common battery exchanges, the ringer box was installed under a desk, or other out of the way place, since it did not need a battery or magneto.

Cradle designs were also used at this time, having a handle with the receiver and transmitter attached, separate from the cradle base that housed the magneto crank and other parts. They were larger than the "candlestick" and more popular.

Disadvantages of single wire operation such as crosstalk and hum from nearby AC power wires had already led to the use of twisted pairs and, for long distance telephones, four-wire circuits. Users at the beginning of the 20th century did not place long distance calls from their own telephones but made an appointment to use a special sound proofed long distance telephone booth furnished with the latest technology.

20th Century developments

By 1904 there were over three million phones in the US[3], still connected by manual switchboard exchanges.

What turned out to be the most popular and longest lasting physical style of telephone was introduced in the early 20th century, including Bell's Model 102. A carbon granule transmitter and electromagnetic receiver were united in a single molded plastic handle, which when not in use sat in a cradle in the base unit. The circuit diagram of the Model 102 shows the direct connection of the receiver to the line, while the transmitter was induction coupled, with energy supplied by a local battery. The coupling transformer, battery, and ringer were in a separate enclosure. The dial switch in the base interrupted the line current by repeatedly but very briefly disconnecting the line 1-10 times for each digit, and the hook switch (in the center of the circuit diagram) permanently disconnected the line and the transmitter battery while the handset was on the cradle.

After the 1930s, the base of the telephone also enclosed its bell and induction coil, obviating the old separate ringer box. Power was supplied to each subscriber line by central office batteries instead of the user's local battery which required periodic service. For the next half century, the network behind the telephone grew progressively larger and much more efficient, and after the rotary dial was added the instrument itself changed little until touch-tone signaling started replacing the rotary dial in the 1960s.

The history of mobile phones can be traced back to two-way radios permanently installed in vehicles such as taxicabs, police cruisers, railroad trains, and the like. Later versions such as the so-called transportables or "bag phones" were equipped with a cigarette lighter plug so that they could also be carried, and thus could be used as either mobile two-way radios or as portable phones by being patched into the telephone network.

In December 1947, Bell Labs engineers Douglas H. Ring and W. Rae Young proposed hexagonal cell transmissions for mobile phones.[4] Philip T. Porter, also of Bell Labs, proposed that the cell towers be at the corners of the hexagons rather than the centers and have directional antennas that would transmit/receive in 3 directions (see picture at right) into 3 adjacent hexagon cells.[5] [6] The technology did not exist then and the frequencies had not yet been allocated. Cellular technology was undeveloped until the 1960s, when Richard H. Frenkiel and Joel S. Engel of Bell Labs developed the electronics.

On April 3, 1973 Motorola manager Martin Cooper placed a cellular phone call (in front of reporters) to Dr. Joel S. Engel, head of research at AT&T's Bell Labs. This began the era of the handheld cellular mobile phone.

Cable television companies began to use their fast-developing cable networks, with ducting under the streets of the United Kingdom, in the late 1980s, to provide telephony services in association with major telephone companies. One of the early cable operators in the UK, Cable London, connected its first cable telephone customer in about 1990.

21st Century developments

- See also: Telephone -IP telephony

Internet Protocol (IP) telephony (also known as 'Internet telephony') is a service based on the Voice over IP communication protocol (VoIP), a disruptive technology that is rapidly gaining ground against traditional telephone network technologies. In Japan and South Korea up to 10% of subscribers switched to this type of telephone service as of January 2005.

IP telephony uses a broadband Internet connection to transmit conversations as data packets. In addition to replacing the traditional Plain Old Telephone Service POTS system, IP telephony is also competing with mobile phone networks by offering free or lower cost connections via WiFi hotspots. VoIP is also used on private wireless networks which may or may not have a connection to the outside telephone network.

See also

- Alexander Graham Bell

- Antonio Meucci claimed inventor of the telephone

- Canadian Parliamentary Motion on Alexander Graham Bell

- Carbon microphone

- Charles Bourseul claimed inventor of the telephone

- Elisha Gray

- Elisha Gray and Alexander Bell Controversy

- History of mobile phones

- History of telecommunication

- Invention of the telephone

- Johann Philipp Reis claimed inventor of the telephone

- Private branch exchange

- Telephone

- Telephone exchange

- Thomas Edison's Carbon telephone transmitter greatly improved the telephone's sound quality

- Timeline of the telephone

References

- Citations

- ^ Jones, R. Victor Samuel Thomas von Sömmering's "Space Multiplexed" Electrochemical Telegraph (1808-10), Harvard University website. Attributed to "Semaphore to Satellite" , International Telecommunication Union, Geneva 1965. Retrieved 2009-05-01

- ^ http://www.telephonymuseum.com/ringer_boxes.htm

- ^ AT&T: History: Origins

- ^ 1947 memo by Douglas H. Ring proposing hexagonal cells

- ^ article by Tom Farley "Cellular Telephone Basics"

- ^ interview of Joel S. Engel, page 17 (image 18)

- General Information

- Baker, Burton H. (2000), The Gray Matter: The Forgotten Story of the Telephone, Telepress, St. Joseph, MI, 2000. ISBN 0-615-11329-X

- Bruce, Robert V. (1990), Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1990.

- Casson, Herbert N. (1910). "The Birth Of The Telephone: Its Invention Not An Accident But The Working Out Of A Scientific Theory". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XIX: 12669–12683.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|title=|month=ignored (help) - Casson, Herbert N. (1910). "The Future Of The Telephone: The Dawn Of A New Era Of Expansion". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XX: 12903–12918.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|title=|month=ignored (help) - Coe, Lewis (1995), The Telephone and Its Several Inventors: A History, McFarland, North Carolina, 1995. ISBN 0-7864-0138-9

- Evenson, A. Edward (2000), The Telephone Patent Conspiracy of 1876: The Elisha Gray - Alexander Bell Controversy, McFarland, North Carolina, 2000. ISBN 0-7864-0883-9

- Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003), The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, IEEE Press and J. Wiley & Sons, 2003. ISBN 0-471-20505-2

- Josephson, Matthew (1992), Edison: A Biography, Wiley, 1992. ISBN 0-471-54806-5