Conrail: Difference between revisions

m →Pre-history: 1973-1976: Fixed short line link ambiguity. |

|||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

The Erie Lackawanna had been formed in 1960 as a merger of the [[Erie Railroad]] and [[Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad]]. It too was bankrupt, but was somewhat stronger financially than the others. It was ruled reorganizable under [[Chapter 77]] on April 30, 1974 (as had the [[Boston and Maine Railroad]]), but on January 9, 1975, with no end to its losses in sight, its trustees reconsidered and asked for inclusion. The Final System Plan assigned a major section of the EL, from northern [[New Jersey]] west to northeast [[Ohio]], to be sold to the [[Chessie System]], which would help spur [[competition]] in Conrail's territory. Chessie however could not reach an agreement with EL [[labor union]]s, and in February 1976 announced that it would not be buying the EL section. The USRA hurriedly assigned large amounts of [[trackage rights]] to the [[Delaware and Hudson Railway]], allowing it to compete in the [[Philadelphia, Pennsylvania]] and [[Washington, DC]] markets. |

The Erie Lackawanna had been formed in 1960 as a merger of the [[Erie Railroad]] and [[Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad]]. It too was bankrupt, but was somewhat stronger financially than the others. It was ruled reorganizable under [[Chapter 77]] on April 30, 1974 (as had the [[Boston and Maine Railroad]]), but on January 9, 1975, with no end to its losses in sight, its trustees reconsidered and asked for inclusion. The Final System Plan assigned a major section of the EL, from northern [[New Jersey]] west to northeast [[Ohio]], to be sold to the [[Chessie System]], which would help spur [[competition]] in Conrail's territory. Chessie however could not reach an agreement with EL [[labor union]]s, and in February 1976 announced that it would not be buying the EL section. The USRA hurriedly assigned large amounts of [[trackage rights]] to the [[Delaware and Hudson Railway]], allowing it to compete in the [[Philadelphia, Pennsylvania]] and [[Washington, DC]] markets. |

||

On the other hand, the [[Michigan|State of Michigan]] decided to keep the full [[Ann Arbor Railroad (1895-1976)|Ann Arbor Railroad]], of which Conrail would run only the southernmost portion, operational. Michigan bought it and the whole line was operated by Conrail for several years until it was sold to a [[short line]].<!--needs details--> |

On the other hand, the [[Michigan|State of Michigan]] decided to keep the full [[Ann Arbor Railroad (1895-1976)|Ann Arbor Railroad]], of which Conrail would run only the southernmost portion, operational. Michigan bought it and the whole line was operated by Conrail for several years until it was sold to a [[Short-line railroad|short line]].<!--needs details--> |

||

===A large system becomes profitable: 1976-1997=== |

===A large system becomes profitable: 1976-1997=== |

||

Revision as of 18:18, 23 March 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

| File:Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) logo.png | |

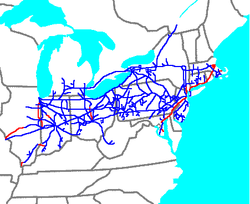

Conrail system map with trackage rights in red. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Reporting mark | CR |

| Locale | Northeast U.S. |

| Dates of operation | 1976–1999 |

The Consolidated Rail Corporation, commonly known as Conrail (reporting mark CR), was the primary Class I railroad in the Northeast U.S. between 1976 and 1999. The federal government created it to take over the potentially profitable lines of bankrupt carriers, including the Penn Central Transportation Company and Erie Lackawanna Railway. With the benefit of regulatory changes, Conrail began to turn a profit in the 1980s and was turned over to private investors in 1987. The two remaining Class I railroads in the East, CSX Transportation and the Norfolk Southern Railway (NS), agreed in 1997 to split the system approximately equally, returning rail freight competition to the Northeast by essentially undoing the 1968 merger of the Pennsylvania Railroad and New York Central Railroad that created Penn Central. Following Surface Transportation Board approval, CSX and NS took control in August 1998, and on June 1, 1999, began operating their portions of Conrail.

The old company remains a jointly-owned subsidiary, with CSX and NS owning respectively 42% and 58% of its stock, corresponding to how much of Conrail's lines they acquired. Each parent, however, has an equal voting interest. The primary asset retained by Conrail is ownership of the three Shared Assets Areas in New Jersey, Philadelphia, and Detroit. Both CSX and NS have the right to serve all shippers in these areas, paying Conrail for the cost of maintaining and improving trackage. They also make use of Conrail to perform switching and terminal services within the areas, but not as a common carrier, since contracts are signed between shippers and CSX or NS. Conrail also retains various support facilities including maintenance-of-way and training, as well as a 51% share in the Indiana Harbor Belt Railroad.

History

Pre-history: 1973-1976

In the years leading to 1973, the freight railroad system of the U.S. was collapsing. Even after the government-funded Amtrak took over intercity passenger service in 1971, railroad companies continued to lose money due to extensive government regulations, competition from other transportation modes, and other factors. The Penn Central Railroad, formed in 1968 by the merger of the New York Central Railroad and Pennsylvania Railroad (and supplemented in 1969 by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad), declared bankruptcy in 1970, less than three years into its existence. The PC was a hopelessly entangled mess with almost no planning carried out prior to the merger between the Pennsylvania Railroad and New York Central. For instance, each company's corporate cultures could not have been more different, creating much of the problems Penn Central experienced. At its lowest point the PC was losing over $1 million a day and trains were becoming lost all over the railroad.[citation needed] In 1972, Hurricane Agnes extensively damaged the already run-down Northeast railway network and threatened the solvency of even more railroads, including the somewhat more solvent Erie Lackawanna. In mid-1973, under Judge John P. Fullam, the bankrupt Penn Central threatened to end all operations by the end of the year if they did not receive government aid by October 1. At that time it would liquidate and cease operating completely, immediately threatening freight and passenger traffic in the United States. The Congress quickly came up with a bill to nationalize the bankrupt railroads. The Association of American Railroads, which opposed nationalization, submitted an alternate proposal for a government-funded private company. Fullam kept the Penn Central company operating into 1974, when, on January 2, after threatening a veto, President Nixon signed the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973 into law. The 3R Act, as it was called, provided interim funding to the bankrupt railroads and defined a new Consolidated Rail Corporation under the AAR's plan.

The 3R Act also formed the United States Railway Association, another government corporation, taking over the powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission with respect to allowing the bankrupt railroads to abandon unprofitable lines. The USRA was incorporated February 1, 1974, and Edward G. Jordan, an insurance executive from California, was named president on March 18 by Nixon. Arthur D. Lewis of Eastern Air Lines was appointed chairman April 30, and the rest of the board was named May 30 and sworn in July 11.

Under the 3R Act, the USRA was to create a Final System Plan to decide which lines should be included in the new Consolidated Rail Corporation. Unlike most railroad consolidations, only the designated lines were to be taken over. Other lines would be sold to Amtrak, various state governments, transportation agencies, and solvent railroads. The few remaining lines were to remain with the old companies along with all previously abandoned lines, many stations, and all non-rail related properties, thus converting most of the old companies into solvent property holding companies. The plan was unveiled July 26, 1975, consisting of lines from Penn Central and six other companies—the Ann Arbor Railroad (bankrupt 1973), Erie Lackawanna Railway (1972), Lehigh Valley Railroad (1970), Reading Company (1971), Central Railroad of New Jersey (1967) and Lehigh and Hudson River Railway (1972). Controlled railroads and jointly owned railroads such as Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines were also included (see list of railroads transferred to Conrail for a full list). It was approved by Congress on November 9, and on February 5, 1976 President Ford signed the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976, which included this Final System Plan, into law.

The Erie Lackawanna had been formed in 1960 as a merger of the Erie Railroad and Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. It too was bankrupt, but was somewhat stronger financially than the others. It was ruled reorganizable under Chapter 77 on April 30, 1974 (as had the Boston and Maine Railroad), but on January 9, 1975, with no end to its losses in sight, its trustees reconsidered and asked for inclusion. The Final System Plan assigned a major section of the EL, from northern New Jersey west to northeast Ohio, to be sold to the Chessie System, which would help spur competition in Conrail's territory. Chessie however could not reach an agreement with EL labor unions, and in February 1976 announced that it would not be buying the EL section. The USRA hurriedly assigned large amounts of trackage rights to the Delaware and Hudson Railway, allowing it to compete in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Washington, DC markets.

On the other hand, the State of Michigan decided to keep the full Ann Arbor Railroad, of which Conrail would run only the southernmost portion, operational. Michigan bought it and the whole line was operated by Conrail for several years until it was sold to a short line.

A large system becomes profitable: 1976-1997

Conrail was incorporated in Pennsylvania on October 25, 1974, and operations began April 1, 1976. The theory was that if the service was improved through increased capital investment, the economic basis of the railroad would be improved. During its first seven years, Conrail proved to be highly unprofitable, despite receiving billions of dollars of assistance from Congress. The corporation declared enormous losses on its federal income tax returns from 1976 through 1982, resulting in an accumulated net operating loss of $2.2 billion during that period. Congress once again reacted with support by passing the Northeast Rail Service Act of 1981 (45 U.S. Sec. 1101 et seq.), which amended portions of the Regional Rail Reorganization Act by exempting Conrail from liability for any state taxes (45 U.S.C. 727(c)) and requiring the Secretary of Transportation to make arrangements for the sale of the government's interest in Conrail (45 U.S.C. 761). After NERSA was implemented, Conrail began to improve and reported taxable income between $2 million and $314 million each year from 1983 through 1986.

Although Conrail's government-funded rebuilding of the heavily dilapidated railroad infrastructure and rolling stock it inherited from its six bankrupt predecessors succeeded by the end of the 1970s in improving the physical condition of tracks, locomotives, and freight cars, the fundamental economic regulatory issues remained, and Conrail continued to post losses of as much as $1 million a day. Conrail management, recognizing the need for more regulatory freedoms to address the economic issues, were among the parties lobbying for what became the Staggers Act of 1980, which significantly loosened the Interstate Commerce Commission's rigid economic control of the rail industry. This allowed Conrail and other carriers the opportunity to become profitable and strengthen their finances.

The Staggers Act allowed the setting of rates that would recover capital and operating cost (fully allocated cost recovery) by each and every route mile the railroad operated. There would be no more cross-subsidization of costs between route-miles (i.e., rates on profitable route segments were not set higher to subsidize routes where rates were set at intermodal parity, yet still did recover fully allocated costs). Finally, where current and/or future traffic projections showed that profitable volumes of traffic would not return, the railroads were allowed to abandon those routes, shippers and passengers to other modes of transportation. With the Staggers Act, the railroads, including Conrail, were freed from the requirement to operate services with open ended losses for the public convenience and necessity of those who simply chose rail services as their mode of transportation.

Conrail began turning a profit by 1981, the result of the Staggers Act freedoms and its own managerial improvements under the leadership of L. Stanley Crane, who had been chief executive officer of the Southern Railway. While the Staggers Act helped immensely in allowing all railroads to more easily abandon unprofitable rail lines and set its own freight rate, it was under Crane's leadership that Conrail truly became a profitable operation. Soon after Crane took office in 1981 he shed another 4,400 miles off the Conrail system in the following two years, which accounted for only 1% of the railroad's overall traffic and 2% of its profits while saving it millions of dollars in maintenance costs.[citation needed] The Northeast Rail Service Act of 1981 relieved Conrail of its requirement to provide commuter service on the Northeast Corridor, further improving its finances.

After considerable debate in Congress, the Conrail Privatization Act of 1986 was signed into law by President Reagan on October 21, 1986. The largest initial public offering in US history came on March 26, 1987 when Conrail's stock, worth $1.9 billion, was sold to private investors.

Shift of passenger operations to State or Metropolitan rail authorities

Conrail inherited the commuter rail operations of its predecessor rail lines, and operated them until 1983, when these services were transferred to state or metropolitan transit authorities. Except for MARC, the transit authorities purchased the track and right-of-way on which their commuter operations ran, leaving Conrail freight operations as a tenant.

Metropolitan Boston

Lower Hudson Valley of New York State and southwest Connecticut

New Jersey

Metropolitan Philadelphia

Maryland

Breakup and shared assets: 1997-1999

With Conrail's increasing success, two eastern rail competitors of Conrail engaged in a takeover battle to control the railroad and expand their systems. In 1997, however, the two railroads, CSX Transportation and the Norfolk Southern Railway, struck a compromise agreement to jointly acquire Conrail and split most of its assets between them, with Norfolk Southern acquiring a larger portion of the Conrail network via a larger stock buyout. Under the final agreement approved by the Surface Transportation Board, Norfolk Southern acquired 58 percent of Conrail's assets, including roughly 6,000 Conrail route miles, and CSX received 42 percent of Conrail's assets, including about 3,600 route miles.[2]

The buyout was approved by the Surface Transportation Board (successor agency to the Interstate Commerce Commission) and took place on August 22, 1998. The lines were transferred to two newly-formed limited liability companies, to be subsidiaries of Conrail but leased to CSX and Norfolk Southern, respectively New York Central Lines (NYC) and Pennsylvania Lines (PRR). The NYC and PRR reporting marks, which had passed to Conrail, were also transferred to the new companies, and NS also acquired the CR reporting mark. Operations under CSX and NS began June 1, 1999.

As the names indicated, CSX acquired the former New York Central Railroad main line from New York City and Boston, Massachusetts to Cleveland, Ohio, and the former Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway (NYC Big Four) line to Indianapolis, Indiana (continuing west to East St. Louis, Illinois on a former Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad (PRR Panhandle Route line), while Norfolk Southern got the former Pennsylvania Railroad main line and Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad from Jersey City, New Jersey to Cleveland, and the rest of the former NYC main line west to Chicago, Illinois. Thus the Conrail "X" was neatly split in two, CSX getting one diagonal from Boston to St. Louis and Norfolk Southern the other from New York to Chicago. The two lines cross at a bridge southeast of downtown Cleveland (41°26′49″N 81°37′37″W / 41.447°N 81.627°W), where the former Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad crosses over the NYC's former Cleveland Short Line Railway around the south side of Cleveland.

In three major metropolitan areas - North Jersey, South Jersey/Philadelphia, and Detroit - Conrail Shared Assets Operations continues to serve as a terminal operating company owned by both CSX and NS. The Conrail Shared Assets Operations arrangement was a concession made to federal regulators who were concerned about the lack of competition in certain rail markets and logistical problems associated with the breaking up the Conrail operations as they existed in densely populated areas with many local customers. The smaller Conrail operation that exists today serves rail freight customers in these markets on behalf of its two owners. A fourth area, the former Monongahela Railway in southwest Pennsylvania, was originally owned jointly by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Pennsylvania Railroad and Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad. Conrail absorbed the company in 1993, and assigned trackage rights to CSX, the successor to the B&O and P&LE. With the Conrail breakup, those lines are owned by NS, but the CSX trackage rights are still in place.

Locomotives

Though Conrail was divided in 1999 between Norfolk Southern Railway and CSX Transportation, some locomotives still bear its name, albeit with the current railroad's number "patched" over the original Conrail number. Many CR units have similar features such as, "Bright Future" blue paint, flashing ditch lights, and Leslie RS3L horns.

Signals

Since Conrail acquired so many separate railways, and the North American railway signalling system is not standardized, operators needed to qualify on as many as seven different signaling systems. The varying systems include, but are not limited to, the Pennsylvania's position light signals, the NYC's searchlight signals and tri-light signals. Most of the existing technologies were defined by NORAC.[3] Conrail itself even had its own, unique tri-light signal modernization program that was applied to many routes. Today, most Northeastern railroads associated with former Conrail assets are working towards standardization of all systems as traffic-light-style signals. Meanwhile, Amtrak uses a modified version of Pennsylvania's position light signals called the Position Color Lights.

Preservation

The Conrail Historical Society was formed to preserve and restore equipment, items pertaining to, and photographs of the Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail). The Society currently has over 700 members and they have also preserved an operating class N7E former Erie Lackawanna Railway caboose.

See also

Notes

- ^ Maryland Transit Administration

- ^ answers.com

- ^ http://www.railroad-signaling.com/aspects.html NORAC signal aspect reference

References

- Timothy Jacobs, The History of the Pennsylvania Railroad, ISBN 0-517-63351-5

- PRR Chronology

- H. Roger Grant, Life and death of Erie Lackawanna, Trains February 1992

- Bill Stephens and Craig Sanders, Cleveland: center of controversy, Trains July 1998

External links

- Conrail official site

- Conrail Historical Society

- Decision FD-33388 (Surface Transportation Board final decision about the Conrail split)

- List and Family Trees of North American Railroads

Books

- Withers, Paul, (1997) Conrail, The Final Years 1992-1997 Withers Publishing. ISBN 978-1881411154

- Conrail

- Railway companies established in 1974

- Former Class I railroads in the United States

- Defunct Connecticut railroads

- Defunct Delaware railroads

- Defunct Washington, D.C. railroads

- Defunct Illinois railroads

- Defunct Indiana railroads

- Defunct Kentucky railroads

- Defunct Maryland railroads

- Defunct Massachusetts railroads

- Defunct Michigan railroads

- Defunct Missouri railroads

- Defunct New Jersey railroads

- Defunct New York railroads

- Defunct Ohio railroads

- Defunct Ontario railways

- Defunct Pennsylvania railroads

- Defunct Rhode Island railroads

- Defunct Quebec railways

- Defunct Virginia railroads

- Defunct West Virginia railroads

- Chicagoland railroads

- Norfolk Southern Railway

- CSX Transportation

- Rail cooperatives

- Government-owned companies in the United States

- Predecessors of CSX Transportation

- Predecessors of the Norfolk Southern Railway