Cold Comfort Farm: Difference between revisions

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==Inspirations== |

==Inspirations== |

||

As a parody of the "loam and lovechild" genre of historical novel, ''Cold Comfort Farm'' alludes specifically to a number of novels both in the past and currently in vogue when Gibbons was writing. Nicola Humble observes, the influence of [[Emily Bronte]]'s ''[[Wuthering Heights]]'' is arguably closest to the surface of the novel, and, indeed, Gibbons' novel might be conceived of as a re-writing of Bronte's work, combined with elements of her sister [[Charlotte Bronte]]'s ''[[Jane Eyre]]'': 'the flighty Elfine is a version of Cathy; the darkly-brooding Seth is a type of [[Heathcliff]], and their mad mother, Judith, is a sort of Bertha Mason'.<ref> Nicola Humble, ''The Feminine Middlebrow Novel, 1920s to 1950s: Class Domesticity and Boheminaism'' (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001) p. 180 </ref> In contrast, in ''Cold Comfort Farm, D. H. Lawrence, and English Literary Culture Between the Wars'', Faye Hammil cites the works of [[Sheila Kaye-Smith]] and [[Mary Webb]] as the chief influences.<ref name=hammill>''Cold Comfort Farm, D. H. Lawrence, and English Literary Culture Between the Wars'', Faye Hammill, Modern Fiction Studies 47.4 (2001) 831-854</ref> According to Hammill, the farm is modelled on Dormer House in Webb's ''[[The House in Dormer Forest]]'', Aunt Ada Doom on Mrs. Velindre in the same book,<ref name=hammill/> the farm-obsessed Reuben on a character in Kaye-Smith's ''[[Sussex Gorse]]'', and the Quivering Brethren on the Colgate Brethren in Kaye-Smith's ''[[Susan Spray]]''.<ref name=hammill/> |

As a parody of the "loam and lovechild" genre of historical novel, ''Cold Comfort Farm'' alludes specifically to a number of novels both in the past and currently in vogue when Gibbons was writing. Nicola Humble observes, the influence of [[Emily Bronte]]'s ''[[Wuthering Heights]]'' is arguably closest to the surface of the novel, and, indeed, Gibbons' novel might be conceived of as a re-writing of Bronte's work, combined with elements of her sister [[Charlotte Bronte|Charlotte]]'s ''[[Jane Eyre]]'': 'the flighty Elfine is a version of Cathy; the darkly-brooding Seth is a type of [[Heathcliff]], and their mad mother, Judith, is a sort of Bertha Mason'.<ref> Nicola Humble, ''The Feminine Middlebrow Novel, 1920s to 1950s: Class Domesticity and Boheminaism'' (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001) p. 180 </ref> In contrast, in ''Cold Comfort Farm, D. H. Lawrence, and English Literary Culture Between the Wars'', Faye Hammil cites the works of [[Sheila Kaye-Smith]] and [[Mary Webb]] as the chief influences.<ref name=hammill>''Cold Comfort Farm, D. H. Lawrence, and English Literary Culture Between the Wars'', Faye Hammill, Modern Fiction Studies 47.4 (2001) 831-854</ref> According to Hammill, the farm is modelled on Dormer House in Webb's ''[[The House in Dormer Forest]]'', Aunt Ada Doom on Mrs. Velindre in the same book,<ref name=hammill/> the farm-obsessed Reuben on a character in Kaye-Smith's ''[[Sussex Gorse]]'', and the Quivering Brethren on the Colgate Brethren in Kaye-Smith's ''[[Susan Spray]]''.<ref name=hammill/> |

||

The speech of the Sussex characters is a parody of rural dialects (in particular Sussex and West Country accents — another parody of novelists who use phonics to portray various accents and dialects) and is sprinkled with fake but authentic-sounding local vocabulary such as ''mollocking'' (Seth's favourite activity, undefined but invariably resulting in the pregnancy of a local maid), ''sukebind'' (a weed whose flowering in the spring symbolises the quickening of sexual urges in man and beast; the word is presumably formed by analogy to 'woodbine', [[honeysuckle]] and [[bindweed]]), ''scranletting'' (ploughing), and ''clettering'' (an impractical method used by Adam for washing dishes, which involves scraping them with a dry twig or ''clettering stick''). |

The speech of the Sussex characters is a parody of rural dialects (in particular Sussex and West Country accents — another parody of novelists who use phonics to portray various accents and dialects) and is sprinkled with fake but authentic-sounding local vocabulary such as ''mollocking'' (Seth's favourite activity, undefined but invariably resulting in the pregnancy of a local maid), ''sukebind'' (a weed whose flowering in the spring symbolises the quickening of sexual urges in man and beast; the word is presumably formed by analogy to 'woodbine', [[honeysuckle]] and [[bindweed]]), ''scranletting'' (ploughing), and ''clettering'' (an impractical method used by Adam for washing dishes, which involves scraping them with a dry twig or ''clettering stick''). |

||

Revision as of 11:53, 16 July 2010

| File:Cold Comfort Farm book.jpg Cover of 1977 Penguin edition | |

| Author | Stella Gibbons |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Comic novel, Satire |

| Publisher | Longmans |

Publication date | 1932 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | xii, 307 pp |

| ISBN | [[Special:BookSources/0141441593+%28current+%5B%5BPenguin+Books%7CPenguin%5D%5D+Classics+edition%29 |0141441593 (current Penguin Classics edition)]] Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

| OCLC | 44833067 |

Cold Comfort Farm is a comic novel by Stella Gibbons, published in 1932. It parodies the romanticised, sometimes doom-laden accounts of rural life popular at the time, by writers such as Mary Webb. Gibbons was working for the Evening Standard in 1928 when they decided to serialise Webb's first novel, The Golden Arrow, and had the job of summarising the plot of earlier installments. Other novelists in the tradition parodied by Cold Comfort Farm are D. H. Lawrence, Sheila Kaye-Smith and Thomas Hardy; and going further back, Mary E Mann and the Brontë sisters.

Plot summary

Having been orphaned, Flora Poste is looking for relatives with whom to live. After rejecting a number of others, she chooses the Starkadders, relatives on her mother's side, who live on the isolated Cold Comfort Farm, near the fictional Sussex village of Howling. Greeting her as "Robert Poste's child", they take her in to repay some unexplained wrong done to her father.

Each of the extended family has some long-festering emotional problem caused by ignorance, hatred or fear; and the farm is badly run -- supposedly cursed -- and presided over by the unseen presence of Aunt Ada Doom, who is said to be mad through having seen "something nasty in the woodshed" as a child.

Flora, a level-headed urban woman, applies modern common sense to their problems and helps them all adapt to the twentieth century.

Inspirations

As a parody of the "loam and lovechild" genre of historical novel, Cold Comfort Farm alludes specifically to a number of novels both in the past and currently in vogue when Gibbons was writing. Nicola Humble observes, the influence of Emily Bronte's Wuthering Heights is arguably closest to the surface of the novel, and, indeed, Gibbons' novel might be conceived of as a re-writing of Bronte's work, combined with elements of her sister Charlotte's Jane Eyre: 'the flighty Elfine is a version of Cathy; the darkly-brooding Seth is a type of Heathcliff, and their mad mother, Judith, is a sort of Bertha Mason'.[1] In contrast, in Cold Comfort Farm, D. H. Lawrence, and English Literary Culture Between the Wars, Faye Hammil cites the works of Sheila Kaye-Smith and Mary Webb as the chief influences.[2] According to Hammill, the farm is modelled on Dormer House in Webb's The House in Dormer Forest, Aunt Ada Doom on Mrs. Velindre in the same book,[2] the farm-obsessed Reuben on a character in Kaye-Smith's Sussex Gorse, and the Quivering Brethren on the Colgate Brethren in Kaye-Smith's Susan Spray.[2]

The speech of the Sussex characters is a parody of rural dialects (in particular Sussex and West Country accents — another parody of novelists who use phonics to portray various accents and dialects) and is sprinkled with fake but authentic-sounding local vocabulary such as mollocking (Seth's favourite activity, undefined but invariably resulting in the pregnancy of a local maid), sukebind (a weed whose flowering in the spring symbolises the quickening of sexual urges in man and beast; the word is presumably formed by analogy to 'woodbine', honeysuckle and bindweed), scranletting (ploughing), and clettering (an impractical method used by Adam for washing dishes, which involves scraping them with a dry twig or clettering stick).

The writing style often deliberately includes convoluted and overwrought prose with strained metaphors: Gibbons indicates some of the more deliberately purple passages with asterisks.

Characters

In order of appearance, and by location:

In London:

- Flora Poste: the heroine, a nineteen-year old from London whose parents are dead.

- Mary Smiling: a widow, Flora's friend in London.

- Charles Fairford: Flora's second cousin in London, who is studying to become a clergyman.

In Howling, Sussex:

- Judith Starkadder: Flora's cousin, the wife of Amos. She has an unhealthy passion for her own son Seth.

- Seth Starkadder: younger son of Amos and Judith. Handsome and over-sexed. Has a passion for the movies.

- Ada Doom: Judith's mother, a reclusive, miserly widow, owner of the farm, who constantly complains of having seen "something nasty in the woodshed" when she was a girl.

- Adam Lambsbreath: ninety-year-old farm hand, obsessed with his cows and with Elfine.

- Mark Dolour: farm hand.

- Amos Starkadder: Judith's husband, and hellfire preacher at the Church of the Quivering Brethren. ("Ye're all damned!")

- Amos's half-cousins: Micah, married to Susan; Urk, a bachelor who wants to marry Elfine; Ezra, married to Jane; Caraway, married to Lettie; Harkaway.

- Amos's half-brothers: Luke, married to Prue; Mark, divorced from Susan and married to Phoebe.

- Reuben Starkadder: Amos's heir, jealous of anyone who stands between him and his inheritance of the farm.

- Meriam Beetle: hired girl, and mother of Seth's four children (the "jazz band").

- Elfine Starkadder: Judith's intellectual, outdoor-loving daughter, who is besotted with Richard Hawk-Monitor of Hautcouture (pronounced "Howchiker") Hall, the local squire.

- Mrs Beetle: cleaning woman (mother of Meriam, wife of "Agony"), rather more sensible than the Starkadders.

- Mrs Murther: landlady of 'The Condemn'd Man' public house.

- Mr Meyerburg (whom Flora thinks of as 'Mr Mybug'): a writer who pursues Flora and insists that she only refuses him because she is sexually repressed. He is working on a thesis that the works of the Brontë sisters were written by their brother Branwell Brontë. Some critics[who?] suggest that his character is a thinly-veiled parody of D.H. Lawrence.

- Rennet Starkadder: unwanted daughter of Susan Starkadder, fathered by her first husband Mark.

- Dr Müdel: a psychoanalyst called in by Flora for the benefit of Judith.

And also:

- Graceless, Aimless, Feckless and Pointless: the farm's cows, and Adam Lambsbreath's chief charge. Occasionally given to losing extremities.

- Viper: the horse, pulls the trap which is the farm's main transportation.

- Big Business: the bull, spends most of his time inside the barn.

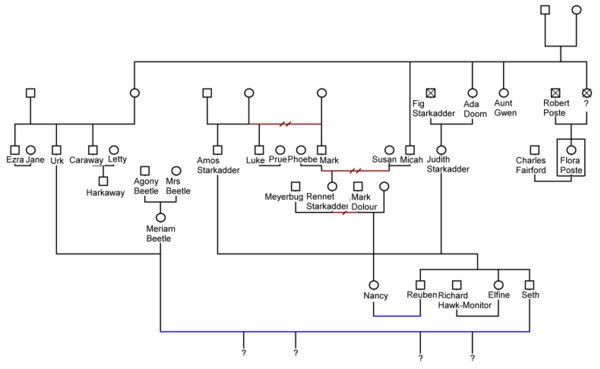

The relationships between the characters are complex. The family tree below seeks to illustrate them as they stand at the end of the novel.

Flora's solutions

The novel ends when Flora, with the aid of her handbook The Higher Common Sense, has solved each character's problem. These solutions are:

- Meriam: Flora introduces her to the concept of contraception.

- Seth: Flora introduces him to a Hollywood film director, Earl P. Neck, who hires him as a screen idol.

- Amos: Flora persuades him to buy a Ford van and become a travelling preacher. He loses interest in running the farm and hands it over to Reuben.

- Elfine: Flora teaches her some social graces and dress sense, Richard Hawk-Monitor realizes he is in love with her and proposes.

- Urk: forgets his desire for Elfine and marries Meriam.

- Mr Mybug: falls in love with and marries Rennet.

- Reuben: asks Flora to marry him but she sidesteps the offer and suggests Mark Dolour's daughter Nancy as more suitable.

- Judith: Flora hires a psychoanalyst, Dr Müdel, who, over lunch, transfers Judith's obsession from Seth to himself until he can set her interest on old churches instead.

- Ada: Flora uses a copy of Vogue magazine to tempt her to join the twentieth century, and spend some of her fortune on living the high life in Paris.

- Adam: is given a job as cow-herd at Hautcouture Hall after Elfine's marriage.

- Graceless, Aimless, Feckless and Pointless: go with Adam to Hautcouture Hall

- Big Business: Flora lets him out into the sunlight.

- Flora: marries Charles.

Future setting

An aspect of the novel not included in many recent adaptations was the novel's near future setting. Although the book was published in 1932, the setting is an unspecified near future following a 1946 "Anglo-Nicaraguan War". The background includes such developments such as video phones, aircraft postal services, and such major demographic changes in London as residential districts south of the Thames having become fashionable.[3]

Sequels and responses

Stella Gibbons wrote two follow-ups. Christmas at Cold Comfort Farm (1940), a short story collection of which Christmas was the first, is a prequel of sorts, set before Flora's arrival at the farm, and is a parody of an "old Englishe" rural Christmas.[4]

A sequel, Conference at Cold Comfort Farm (1949), is set 16 years later and satirises the social and cultural scene of the period. The farm has been refurbished as a museum in faux-rustic style and becomes the venue for a conference of the International Thinkers' Group.[5]

Sheila Kaye-Smith, often said to be one of the rural writers parodied by Gibbons in CCF, arguably gets her own back with a tongue-in-cheek reference to CCF within a subplot of A Valiant Woman (1939), set in a rapidly modernising village (Pearce:2008). Upper middle-class teenager, Lucia, turns from writing charming rural poems to a great Urban Proletarian Novel: "… all about people who aren't married going to bed in a Manchester slum and talking about the Means Test." Her philistine grandmother is dismayed: she prefers ‘cosy’ rural novels, and knows Lucia is ignorant of proletarian life:

"That silly child! Did she really think she could write a novel? Well, of course, modern novels might encourage her to think so. There was nothing written nowadays worth reading. The book on her knee was called Cold Comfort Farm and had been written by a young woman who was said to be very clever and had won an important literary prize. But she couldn't get on with it at all. It was about life on a farm, but the girl obviously knew nothing about country life. To anyone who, like herself, had always lived in the country, the whole thing was too ridiculous and impossible for words."

Kaye-Smith layers the ironies here within a subtext of contesting claims to authenticity. Not only does the older woman fail to recognise CCF is a comedy, but her family own farms without ever working the land themselves, or tried to make a basic living from any manual labour. Kaye-Smith herself was a townie who moved to a small village (where she converted an oasthouse to a large home). However she allows Lucia to succeed: her novel The Price of Bread is published (by a left-wing book club) and becomes a success.

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

Cold Comfort Farm has been adapted for television twice by the BBC. In 1968 a three-part serial was made, starring Sarah Badel as Flora Poste, Brian Blessed as Reuben, Peter Egan as Seth, and Alastair Sim as Amos. In 1995 there was a UK made-for-TV film, which was generally well-received, with critics like the New York Times' Janet Maslin writing that this screen version "gets it exactly right."[6] The film starred Kate Beckinsale as Flora, Joanna Lumley as her friend and mentor Mary Smiling, Rufus Sewell as Seth, Ian McKellen as Amos Starkadder, Eileen Atkins as Judith, Stephen Fry as Mybug, Miriam Margolyes as Mrs. Beetle, and Angela Thorne as Mrs Hawk-Monitor. Character actor Freddie Jones had roles in both productions, as the lascivious Urk in the early production, and as old Adam Lambsbreath in the later one. The 1995 version was produced by Gramercy Pictures, in collaboration with BBC Films and Thames International, and directed by John Schlesinger, from a script by novelist and scholar Sir Malcolm Bradbury. It was filmed on location at Brightling, East Sussex. In 1996, this new version also had a brief theatrical run in North America and Australia.[7] Cold Comfort Farm (1995) is available on DVD in both the US and UK. The earlier 1968 television serialisation is unavailable.

The BBC produced a four-part radio adaptation in 1981. Patricia Gallimore played Flora, and Miriam Margolyes played Mrs. Beetle. Christmas at Cold Comfort Farm, read by Kenneth Williams, was on Radio 4's Morning Story on Christmas Eve, 1975 [8], and an adaptation of Conference at Cold Comfort Farm by Elizabeth Proud was broadcast in two parts (There have always been Starkadders at Cold Comfort Farm and Reuben's Oath) in January 1995.[9]

The book has also been turned into a play by Paul Doust.[10] The plot was simplified a little in order to make it suitable for the stage. Many characters, including Mybug, Mrs. Beetle, Meriam, Mark Dolour and Mrs. Smiling, are omitted. Meriam's character was merged with Rennet, who ends up with Urk at the end. As a consequence, both Rennet's and Urk's roles are much bigger than in the book. Mrs. Smiling is absent because the action begins with Flora's arrival in Sussex; Charles appears only to drop her off and pick her up again at the end. Mark Dolour, though mentioned several times in the play as a running joke, never appears on stage. Finally, instead of visiting a psychoanalyst to cure her obsession, Judith leaves with Neck at the end.

Sayings entering the English Language

The term "something nasty in the woodshed", alluding to some hidden or metaphorical horror, comes directly from this book.

Notes

- ^ Nicola Humble, The Feminine Middlebrow Novel, 1920s to 1950s: Class Domesticity and Boheminaism (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001) p. 180

- ^ a b c Cold Comfort Farm, D. H. Lawrence, and English Literary Culture Between the Wars, Faye Hammill, Modern Fiction Studies 47.4 (2001) 831-854

- ^ Old official Stella Gibbons website, Reggie Oliver, Internet Archive

- ^ The Roads from Bethlehem: Christmas Literature from Writers Ancient and Modern, Pegram Johnson III, Edna M. Troiano, Westminster John Knox Press, 1993, ISBN 0664221572 Google Books

- ^ Encyclopedia of British Humorists, Steven H. Gale, Taylor & Francis, 1996, ISBN 0824059905 Google Books

- ^ [1]

- ^ Review by Roger Ebert

- ^ Full Christmas viewing programmes, Stanley Reynolds; Michael Ratcliffe, The Times, Dec 24, 1975

- ^ Dreams recalled, David Wade, The Times, Jan 22, 1983.

- ^ Plays by Paul Doust

References

- Bleiler, Everett (1948). The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. Chicago: Shasta Publishers. p. 126.

- Cavaliero, Glen (1977) The Rural Tradition in the English Novel 1900-39: Macmillan

- Humble, Nicola (2001) The Feminine Middlebrow Novel 1920s - 1950s: Oxford University Press

- Kaye-Smith, Sheila (1939) A Valiant Woman: Cassell & Co Ltd

- Pearce, H (2008) "Sheila’s Response to Cold Comfort Farm", The Gleam: Journal of the Sheila Kaye-Smith Society, No 21.

- Trodd, Anthea (1980) Women's Writing in English: Britain 1900-1945: Longmans.

- Cold Comfort Farm at IMDb (1968 version)

- Cold Comfort Farm at IMDb (1995 version)