John Lennon: Difference between revisions

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

===1970–80: Solo career=== |

===1970–80: Solo career=== |

||

==== |

====1970–72: Initial post-Beatles years==== |

||

Following the Beatles' break-up in 1970, Lennon and Ono went through [[Primal therapy#John Lennon|primal therapy]] with Dr. [[Arthur Janov]] in Los Angeles, California. Designed to release emotional pain from early childhood, the therapy entailed two half-days a week with Janov for four months; he had wanted to treat the couple for longer, but they felt no need to continue and returned to London.{{sfn|Harry|2000b|pp=408–410}} Lennon's emotional debut solo album, ''[[John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band]]'' (1970), was received with high praise. Critic [[Greil Marcus]] remarked, "John's singing in the last verse of 'God' may be the finest in all of rock."{{sfn|Blaney|2005|p=56}} The album spawned the singles "[[Mother (John Lennon song)|Mother]]", in which Lennon confronted his feelings of childhood rejection,{{sfn|Harry|2000b|pp=640-641}} and the Dylanesque "[[Working Class Hero]]", a bitter attack against the bourgeois social system which, due to the lyric "you're still fucking peasants", fell foul of broadcasters.{{sfn|Riley|2002|p=375}}{{sfn|Schechter|1997|p=106}} The same year, [[Tariq Ali]]'s revolutionary political views, expressed when he interviewed Lennon, inspired the singer to write "[[Power to the People (song)|Power to the People]]". Lennon also became involved with Ali during a protest against [[Oz (magazine)|''Oz'' magazine]]'s prosecution for alleged obscenity. Lennon denounced the proceedings as "disgusting fascism", and he and Ono (as Elastic Oz Band) released the single "God Save Us/Do the Oz" and joined marches in support of the magazine.{{sfn|Wiener|1990|p=157}} |

Following the Beatles' break-up in 1970, Lennon and Ono went through [[Primal therapy#John Lennon|primal therapy]] with Dr. [[Arthur Janov]] in Los Angeles, California. Designed to release emotional pain from early childhood, the therapy entailed two half-days a week with Janov for four months; he had wanted to treat the couple for longer, but they felt no need to continue and returned to London.{{sfn|Harry|2000b|pp=408–410}} Lennon's emotional debut solo album, ''[[John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band]]'' (1970), was received with high praise. Critic [[Greil Marcus]] remarked, "John's singing in the last verse of 'God' may be the finest in all of rock."{{sfn|Blaney|2005|p=56}} The album spawned the singles "[[Mother (John Lennon song)|Mother]]", in which Lennon confronted his feelings of childhood rejection,{{sfn|Harry|2000b|pp=640-641}} and the Dylanesque "[[Working Class Hero]]", a bitter attack against the bourgeois social system which, due to the lyric "you're still fucking peasants", fell foul of broadcasters.{{sfn|Riley|2002|p=375}}{{sfn|Schechter|1997|p=106}} The same year, [[Tariq Ali]]'s revolutionary political views, expressed when he interviewed Lennon, inspired the singer to write "[[Power to the People (song)|Power to the People]]". Lennon also became involved with Ali during a protest against [[Oz (magazine)|''Oz'' magazine]]'s prosecution for alleged obscenity. Lennon denounced the proceedings as "disgusting fascism", and he and Ono (as Elastic Oz Band) released the single "God Save Us/Do the Oz" and joined marches in support of the magazine.{{sfn|Wiener|1990|p=157}} |

||

Revision as of 14:00, 8 December 2010

John Lennon |

|---|

John Winston Ono Lennon, MBE (9 October 1940 – 8 December 1980) was an English musician and singer-songwriter who rose to worldwide fame as one of the founding members of The Beatles and, with Paul McCartney, formed one of the most successful songwriting partnerships of the 20th century. Born and raised in Liverpool, Lennon became involved as a teenager in the skiffle craze; his first band, The Quarrymen, evolved into The Beatles in 1960. As the group disintegrated towards the end of the decade, Lennon embarked on a solo career that would produce the critically acclaimed albums John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band and Imagine, and iconic songs such as "Give Peace a Chance" and "Imagine". Lennon disengaged himself from the music business in 1975 to devote time to his family, but re-emerged in 1980 with a new album, Double Fantasy. He was murdered three weeks after its release.

Lennon revealed a rebellious nature and acerbic wit in his music, his writing, his drawings, on film, and in interviews, and he became controversial through his political activism. He moved to New York City in 1971, where his criticism of the Vietnam War resulted in a lengthy attempt by Richard Nixon's administration to deport him, while his songs were adopted as anthems by the anti-war movement.

As of 2010, Lennon's solo album sales in the United States exceed 14 million units, and as writer, co-writer or performer, he is responsible for 27 number one singles on the US Hot 100 chart. In 2002, a BBC poll on the 100 Greatest Britons voted him eighth, and in 2008, Rolling Stone ranked him the fifth greatest singer of all time. He was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1987 and into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994.

History

1940–57: Early years

Lennon was born in war-time England, on 9 October 1940 at Liverpool Maternity Hospital, to Julia and Alfred Lennon, a merchant seaman who was away at the time of his son's birth.[1] John Lennon was named after his paternal grandfather, John "Jack" Lennon, and then-Prime Minister Winston Churchill.[2] His father was often away from home but sent regular pay cheques to 9 Newcastle Road, Liverpool, where Lennon lived with his mother,[3] but the cheques stopped when he went absent without leave in February 1944.[4][5] When he eventually came home six months later, he offered to look after the family, but Julia—by then pregnant with another man's child—rejected the idea.[6] After her sister, Mimi Smith, twice complained to Liverpool's Social Services, Julia handed the care of Lennon over to her. In July 1946, Lennon's father visited Smith and took his son to Blackpool, secretly intending to emigrate to New Zealand with him.[7] Julia followed them—with her partner at the time, 'Bobby' Dykins—and after a heated argument his father forced the five-year-old to choose between them. Lennon twice chose his father, but as his mother walked away, he began to cry and followed her.[8] It would be 20 years before he had contact with his father again.[9]

Throughout the rest of his childhood and adolescence, he lived with his aunt and uncle, Mimi and George Smith, at Mendips, 251 Menlove Avenue, Woolton, who had no children of their own.[10] His aunt bought him volumes of short stories, and his uncle, a dairyman at his family's farm, bought him a mouth organ and engaged him in solving crossword puzzles.[11] Julia visited Mendips on a regular basis, and when he was 11-years-old he often visited her at 1 Blomfield Road, Liverpool, where she played him Elvis Presley records, and taught him the banjo, playing "Ain't That a Shame" by Fats Domino.[12]

In September 1980 he talked about his family and his rebellious nature:

Part of me would like to be accepted by all facets of society and not be this loudmouthed lunatic musician. But I cannot be what I am not. Because of my attitude, all the other boys' parents ... instinctively recognised what I was, which was a troublemaker, meaning I did not conform and I would influence their kids, which I did. ... I did my best to disrupt every friend's home ... Partly, maybe, it was out of envy that I didn't have this so-called home, but I really did ... There were five women who were my family. Five strong, intelligent women. Five sisters. Those women were fantastic ... that was my first feminist education ... One happened to be my mother ... she just couldn't deal with life. She had a husband who ran away to sea and the war was on and she couldn't cope with me, and when I was four-and-a-half, I ended up living with her elder sister ... the fact that I wasn't with my parents made me see that parents are not gods.[13]

He regularly visited his cousin Stanley Parkes in Fleetwood. Seven years Lennon's senior, Parkes took him on trips, and to local cinemas.[11] During the school holidays, Parkes often visited Lennon with Leila Harvey, another cousin, often travelling to Blackpool two or three times a week to watch shows. They would visit the Blackpool Tower Circus and see artists such as Dickie Valentine, Arthur Askey, Max Bygraves and Joe Loss, with Parkes recalling that Lennon particularly liked George Formby.[14] After Parkes's family moved to Scotland, the three cousins often spent their school holidays together there. Parkes recalled, "John, cousin Leila and I were very close. From Edinburgh we would drive up to the family croft at Durness, which was from about the time John was nine years old until he was about 16."[15] He was 14-years-old when his uncle George died of a liver haemorrhage on 5 June 1955 (aged 52).[16]

Lennon was raised as an Anglican and attended Dovedale Primary School.[17] From September 1952 to 1957, after passing his Eleven-Plus exam, he attended Quarry Bank High School in Liverpool, and was described by Harvey at the time as, "A happy-go-lucky, good-humoured, easy going, lively lad."[18] He often drew comical cartoons which appeared in his own self-made school magazine called The Daily Howl,[19] but despite his artistic talent, his school reports were damning: "Certainly on the road to failure ... hopeless ... rather a clown in class ... wasting other pupils' time."[20]

His mother bought him his first guitar in 1957, an inexpensive Gallotone Champion acoustic for which she "lent" her son five pounds and ten shillings on the condition that the guitar be delivered to her own house, and not Mimi's, knowing well that her sister was not supportive of her son's musical aspirations.[21] As Mimi was sceptical of his claim that he would be famous one day, she hoped he would grow bored with music, often telling him, "The guitar's all very well, John, but you'll never make a living out of it".[22] On 15 July 1958, when Lennon was 17-years-old, his mother, walking home after visiting the Smiths' house, was struck by a car and killed.[23]

Lennon failed all his GCE O-level examinations, and was only accepted into the Liverpool College of Art after his aunt and headmaster intervened.[24] Once at the college, he started wearing Teddy Boy clothes and acquired a reputation for disrupting classes and ridiculing teachers. As a result, he was excluded from the painting class, then the graphic arts course, and was threatened with expulsion for his behaviour, which included sitting on a nude model's lap during a life drawing class.[25] He failed an annual exam, despite help from fellow student and future wife Cynthia Powell, and was "thrown out of the college before his final year."[26]

1957–70: From the Quarrymen to the Beatles

1957–65: Formation, commercial breakout, and touring years

The Beatles evolved from Lennon's first band, the Quarrymen. Named after Quarry Bank High School, the group was established by him in September 1956 when he was 15, and began as a skiffle group.[27] By the summer of 1957 the Quarrymen played a "spirited set of songs" made up of half skiffle, and half rock and roll.[28] Lennon first met Paul McCartney at the Quarrymen's second performance, held in Woolton on 6 July at the St. Peter's Church garden fête, after which McCartney was asked to join the band.[29] Lennon's Aunt Mimi disapproved of McCartney because he was, as she said, "working class",[30] with McCartney's father also disapproving, declaring that Lennon would get his son "into a lot of trouble";[31] although later allowing the fledgling band to rehearse in the McCartney's front room at 20 Forthlin Road.[32] Lennon was 18 when he wrote his first song ("Hello Little Girl", a UK top 10 hit for The Fourmost nearly five years later).[33]

Stuart Sutcliffe, Lennon's friend from art school, joined as bassist,[34] and George Harrison joined the band as lead guitarist.[35] Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Sutcliffe became "The Beatles" in early 1960. In August of that year The Beatles, engaged for a 48-night residency in Hamburg, Germany, asked drummer Pete Best to join them one day before leaving.[36] Lennon was now 19, and his aunt, horrified when he told her about the trip, pleaded with him to continue his art studies instead.[37] After the first Hamburg residency, the band accepted another in April 1961, and a third in April 1962. Like the other band members, Lennon was introduced to Preludin while in Hamburg,[38] and regularly took the drug, as well as amphetamines, as a stimulant during their long, overnight performances.[39]

Brian Epstein, the Beatles' manager from 1962, had no prior experience of artist management, but nevertheless had a strong influence on their early dress code and attitude on stage.[40] Lennon initially resisted Epstein's attempts to encourage the band to present a professional appearance, but eventually complied, saying, "I'll wear a bloody balloon if somebody's going to pay me".[41] McCartney took over on bass after Sutcliffe decided to stay in Hamburg, and drummer Ringo Starr replaced Best, completing the four-piece line-up that would endure until the group's break-up in 1970. After discovering she was pregnant, Lennon married Powell on 23 August 1962, at the Mount Pleasant Register office in Liverpool.[42]

The band's first single, "Love Me Do", was released in October 1962 and reached #17 on the British charts. They recorded their debut album, Please Please Me, in under 10 hours on 11 February 1963—a day when Lennon was suffering the effects of a cold.[43] The Lennon/McCartney songwriting partnership yielded eight of its fourteen tracks. With few exceptions—one being the album title itself—Lennon had yet to bring his love of wordplay to bear on his song lyrics, saying: "We were just writing songs ... pop songs with no more thought of them than that–to create a sound. And the words were almost irrelevant".[44] In a 1987 interview, McCartney said that the other Beatles idolised John: "He was like our own little Elvis ... We all looked up to John. He was older and he was very much the leader; he was the quickest wit and the smartest".[45]

The Beatles achieved mainstream success in the UK around the start of 1963. Lennon was on tour when his first son, Julian, was born in April. During their Royal Variety Show performance, attended by the Queen Mother and other British royalty, Lennon poked fun at his audience: "For our next song, I'd like to ask for your help. For the people in the cheaper seats, clap your hands ... and the rest of you, if you'll just rattle your jewellery."[46] After a year of Beatlemania in the UK, the group's historic February 1964 US debut appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show marked their breakthrough to international stardom. A two-year period of constant touring, moviemaking, and songwriting followed, during which Lennon wrote two books, In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works.[47] The Beatles received recognition from the British Establishment when they were appointed Members of the Order of the British Empire in the Queen's Birthday Honours of 1965.[48]

1966–70: Studio years, break-up and solo beginnings

Lennon grew concerned that fans attending Beatles concerts were unable to hear the music above the screaming of fans, and that the band's musicianship was beginning to suffer as a result.[49] Lennon's "Help!" expressed his own feelings in 1965: "I meant it ... It was me singing 'help'".[50] He had put on weight (he would later refer to this as his "Fat Elvis" period),[51] and felt he was subconsciously seeking change.[52] The following January he was unknowingly introduced to LSD when a dentist, hosting a dinner party attended by Lennon, Harrison and their wives, spiked the guests' coffee with the drug.[53] When they wanted to leave, their host revealed what they had taken, and strongly advised them not to leave the house because of the likely effects. Later, in an elevator at a nightclub, they all believed it was on fire: "We were all screaming ... hot and hysterical."[53] A few months later in March, during an interview with Evening Standard reporter Maureen Cleave, Lennon remarked, "Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink ... We're more popular than Jesus now—I don't know which will go first, rock and roll or Christianity."[54] The comment went virtually unnoticed in England but caused great offence in the US when quoted by a magazine there five months later. The furore that followed—burning of Beatles records, Ku Klux Klan activity, and threats against Lennon—contributed to the band's decision to stop touring.[55]

Deprived of the routine of live performances after their final commercial concert in 1966, Lennon felt lost and considered leaving the band.[56] Since his involuntary introduction to LSD in January, he had made increasing use of the drug, and was almost constantly under its influence for much of the year."[57] According to biographer Ian MacDonald, Lennon's continuous experience with LSD during the year brought him "close to erasing his identity".[58] 1967 saw the release of "Strawberry Fields Forever", hailed by Time magazine for its "astonishing inventiveness",[59] and the group's landmark album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, which revealed Lennon's lyrics contrasting strongly with the simple love songs of the Lennon/McCartney's early years.

In August, after having been introduced to the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the group attended a weekend of personal instruction at his Transcendental Meditation seminar in Bangor, Wales.[60] The group were informed of the sudden death of Epstein during the seminar. "I knew we were in trouble then", Lennon said later. "I didn't have any misconceptions about our ability to do anything other than play music, and I was scared".[61] They later travelled to Maharishi's ashram in India for further guidance, and while there composed most of the songs for The Beatles and Abbey Road.[62]

The anti-war, black comedy How I Won the War, featuring Lennon's only appearance in a non–Beatles full-length film, was shown in cinemas in October 1967.[63] McCartney organised the group's first post-Epstein project,[64] the self written, produced and directed television film Magical Mystery Tour, released in December that year. Whilst the film itself proved to be their first critical flop, its soundtrack release, featuring Lennon's acclaimed, Carroll-inspired "I am the Walrus", was a success.[65][66] With Epstein gone, the band members became increasingly involved in business activities, and in February 1968 they formed Apple Corps, a multimedia corporation comprising Apple Records and several other subsidiary companies. Lennon described the venture as an attempt to achieve, "artistic freedom within a business structure",[67] but his increased drug experimentation and growing preoccupation with Yoko Ono, and McCartney's own marriage plans, left Apple in need of professional management. Lennon asked Lord Beeching to take on the role, but he declined, advising Lennon to go back to making records. Lennon approached Allen Klein, who had managed The Rolling Stones and other bands during the British Invasion. Klein was appointed as Apple’s chief executive by Lennon, Harrison and Starr, but McCartney refused to sign the management contract.[68]

At the end of 1968, Lennon featured in the film The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus (not released until 1996) in the role of a Dirty Mac band member. The supergroup, comprising Lennon, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and Mitch Mitchell, also backed a vocal performance by Ono in the film.[70] Lennon and Ono were married on 20 March 1969, and soon released a series of 14 lithographs called "Bag One" depicting scenes from their honeymoon,[71] eight of which were deemed indecent and most of which were banned and confiscated.[72] Lennon's creative focus continued to move beyond the Beatles and between 1968 and 1969 he and Ono recorded three albums of experimental music together: Unfinished Music No.1: Two Virgins[73] (known more for its cover than for its music), Unfinished Music No.2: Life with the Lions and Wedding Album. In 1969 they formed The Plastic Ono Band, releasing Live Peace in Toronto 1969. In protest at Britain's involvement in the Nigerian Civil War,[74] Lennon returned his MBE medal to the Queen, though this had no effect on his MBE status, which could not be renounced.[75] Between 1969 and 1970 Lennon released the singles "Give Peace a Chance" (widely adopted as an anti-Vietnam-War anthem in 1969),[76] "Cold Turkey" (documenting his withdrawal symptoms after he became addicted to heroin[77]) and "Instant Karma!".

Lennon left the Beatles in September 1969.[78] He agreed not to inform the media while the band renegotiated their recording contract, and was outraged that McCartney publicised his own departure on releasing his debut solo album in April 1970. Lennon's reaction was, "Jesus Christ! He gets all the credit for it!"[79] He later wrote, "I started the band. I disbanded it. It's as simple as that."[80] In later interviews with Rolling Stone, he revealed his bitterness towards McCartney, saying, "I was a fool not to do what Paul did, which was use it to sell a record."[81] He spoke too of the hostility he perceived the other members had towards Ono, and of how he, Harrison, and Starr "got fed up with being sidemen for Paul ... After Brian Epstein died we collapsed. Paul took over and supposedly led us. But what is leading us when we went round in circles?"[82]

1970–80: Solo career

1970–72: Initial post-Beatles years

Following the Beatles' break-up in 1970, Lennon and Ono went through primal therapy with Dr. Arthur Janov in Los Angeles, California. Designed to release emotional pain from early childhood, the therapy entailed two half-days a week with Janov for four months; he had wanted to treat the couple for longer, but they felt no need to continue and returned to London.[83] Lennon's emotional debut solo album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970), was received with high praise. Critic Greil Marcus remarked, "John's singing in the last verse of 'God' may be the finest in all of rock."[84] The album spawned the singles "Mother", in which Lennon confronted his feelings of childhood rejection,[85] and the Dylanesque "Working Class Hero", a bitter attack against the bourgeois social system which, due to the lyric "you're still fucking peasants", fell foul of broadcasters.[86][87] The same year, Tariq Ali's revolutionary political views, expressed when he interviewed Lennon, inspired the singer to write "Power to the People". Lennon also became involved with Ali during a protest against Oz magazine's prosecution for alleged obscenity. Lennon denounced the proceedings as "disgusting fascism", and he and Ono (as Elastic Oz Band) released the single "God Save Us/Do the Oz" and joined marches in support of the magazine.[88]

With Lennon's next album, Imagine (1971), critical response was more guarded. Rolling Stone reported that "it contains a substantial portion of good music" but warned of the possibility that "his posturings will soon seem not merely dull but irrelevant".[91] The album's title track would become an anthem for anti-war movements,[92] while another, "How Do You Sleep?", was a musical attack on McCartney in response to lyrics from Ram that Lennon felt, and McCartney later confirmed,[93] were directed at him and Ono. However, Lennon softened his stance in the mid-70s and said he had written "How Do You Sleep?" about himself.[94] He said in 1980: "I used my resentment against Paul ... to create a song ... not a terrible vicious horrible vendetta ... I used my resentment and withdrawing from Paul and the Beatles, and the relationship with Paul, to write 'How Do You Sleep'. I don't really go 'round with those thoughts in my head all the time".[95]

Lennon and Ono moved to New York in August 1971, and in December released "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)".[96] To advertise the single, they paid for billboards in 12 cities around the world which declared, in the national language, "WAR IS OVER—IF YOU WANT IT".[97] The new year saw the Nixon Administration take what it called a "strategic counter-measure" against Lennon's anti-war propaganda, embarking on what would be a four-year attempt to deport him: embroiled in a continuing legal battle, he was denied permanent residency in the US until 1976.[98]

Recorded as a collaboration with Ono and with backing from the New York band Elephant's Memory, Some Time in New York City was released in 1972. Containing songs about women's rights, race relations, Britain's role in Northern Ireland, and Lennon's problems obtaining a green card,[99] the album was poorly received—unlistenable, according to one critic.[100] "Woman Is the Nigger of the World", released as a US single from the album the same year, was televised on 11 May, on The Dick Cavett Show. Many radio stations refused to broadcast the song because of the word "nigger".[101] Lennon and Ono gave two benefit concerts with Elephant's Memory and guests in New York in aid of patients at the Willowbrook State School mental facility.[102] Staged at Madison Square Garden on 30 August 1972, they were his last full-length concert appearances.[103]

1973–80: More recording, activism and family

While Lennon was recording Mind Games (1973), he and Ono decided to separate. The ensuing eighteen-month period apart, which he later called his "lost weekend",[104] was spent in Los Angeles and New York in the company of May Pang. Mind Games, credited to "the Plastic U.F.Ono Band", was released in November 1973. More positively received than its predecessor, the album was critically assessed as "listenable" but "his worst writing yet" and found Lennon to be "helplessly trying to impose his own gargantuan ego upon an audience ... waiting hopefully for him to chart a new course"[100]. Its title track, "Mind Games", was a top 20 hit in the US and reached number 26 in the UK. Lennon contributed a revamped version of "I'm the Greatest", a song he wrote two years earlier, to Starr's album Ringo (1973), released the same month. (Lennon's 1971 demo appears on John Lennon Anthology.) During 1974 he produced Harry Nilsson's Pussy Cats and the Mick Jagger song "Too Many Cooks (Spoil the Soup)". The latter was destined, for contractual reasons, to remain unreleased for more than thirty years. Pang supplied the recording for its eventual inclusion on The Very Best of Mick Jagger (2007).[105]

Walls and Bridges (1974) yielded Lennon's only number one single in his lifetime, "Whatever Gets You Thru the Night", featuring Elton John on backing vocals and piano.[106] A second single from the album, "#9 Dream", followed before the end of the year. Starr's Goodnight Vienna (1974) again saw assistance from Lennon, who wrote the title track and played piano.[107] On 28 November, Lennon made a surprise guest appearance at Elton John's Thanksgiving concert at Madison Square Garden, in fulfilment of his promise to join the singer in a live show if "Whatever Gets You Thru the Night", a song whose commercial potential Lennon had doubted, reached number one. Lennon performed the song along with "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" and "I Saw Her Standing There".[108]

Lennon co-wrote "Fame", David Bowie's first US number one, and provided guitar and backing vocals for the January 1975 recording.[109] He and Ono were reunited shortly afterwards.[110] The same month, Elton John topped the charts with his own cover of "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds", featuring Lennon on guitar and back-up vocals. Lennon released Rock 'n' Roll (1975), an album of cover songs, in February. Soon afterwards, "Stand By Me", taken from the album and a US and UK hit, became his last single for five years. He made what would be his final stage appearance in the ATV special A Salute to Lew Grade, recorded on 18 April and televised in June.[111] Playing acoustic guitar, and backed by his eight-piece band BOMF (introduced as "Etcetera"), Lennon performed two songs from Rock 'n' Roll ("Slippin' and Slidin'" and "Stand By Me", the latter of which was excluded from the television broadcast) followed by "Imagine".[111] The band wore masks on the backs of their heads, making them appear two-faced, a dig at Grade,[112] with whom Lennon and McCartney had been in conflict because of his control of the Beatles' publishing company. (Dick James had sold his majority share to Grade in 1969.) During "Imagine", Lennon interjected the line "and no immigration too", a reference to his battle to remain in the United States.[99]

When Lennon's second son, Sean, was born on 9 October 1975, he took on the role of househusband, beginning what would be a five-year hiatus from the music industry during which he gave all his attention to his family.[13] Within the month, he fulfilled his contractual obligation to EMI/Capitol for one more album by releasing Shaved Fish, a compilation album of previously recorded tracks. He devoted himself to Sean, rising at 6 am daily to plan and prepare his meals and to spend time with him.[113] He wrote "Cookin' (In the Kitchen of Love)" for Starr's Ringo's Rotogravure (1976), performing on the track in June in what would be his last recording session until 1980.[114] He formally announced his break from music in Tokyo in 1977, saying, "we have basically decided, without any great decision, to be with our baby as much as we can until we feel we can take time off to indulge ourselves in creating things outside of the family."[115] During his career break he created several series of drawings, and drafted a book containing a mix of autobiographical material and what he termed "mad stuff",[116] all of which would be published posthumously.

He emerged from retirement in October 1980 with the single "(Just Like) Starting Over", followed the next month by the album that spawned it. Double Fantasy contained songs, written during a journey to Bermuda on a 43-foot sailing boat the previous June,[117] that reflected Lennon's fulfillment in his new-found stable family life.[118] The album took its title from a species of freesia, seen in the Bermuda Botanical Gardens, whose name Lennon regarded as a perfect description of his marriage to Ono.[119] Sufficient additional material was recorded for a planned follow-up album Milk and Honey (released posthumously in 1984).[120] Released jointly with Ono, Double Fantasy was not well received, drawing comments such as Melody Maker's "indulgent sterility ... a godawful yawn".[121]

December 1980: Murder

At around 10:50 pm on 8 December 1980, as Lennon and Ono returned to their New York apartment in The Dakota, Mark David Chapman shot Lennon in the back four times at the entrance to the building. Lennon was taken to the emergency room of nearby Roosevelt Hospital and was pronounced dead on arrival at 11:07 pm.[122] Earlier that evening, Lennon had autographed a copy of Double Fantasy for Chapman.[123]

Ono issued a statement the next day, saying "There is no funeral for John," ending it with the words, "John loved and prayed for the human race. Please pray the same for him."[124] His body was cremated at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. Ono scattered his ashes in New York's Central Park, where the Strawberry Fields memorial was later created.[125] Chapman pleaded guilty to second degree murder and was sentenced to 20 years to life; as of 2010, he remains in prison, having been repeatedly denied parole.[126][127]

Personal relationships

Cynthia Lennon

Template:Image stack Lennon and Cynthia Powell met in 1957 as fellow students at the Liverpool College of Art.[128] Although being scared of Lennon's attitude and appearance, she heard that he was obsessed with Brigitte Bardot, and changed the colour of her hair to blonde. They danced together at an end-of-term event, and Lennon asked her out, but when she said that she was engaged, he replied, "I didn't ask you to fucking marry me, did I?"[129] She often accompanied him to Quarrymen gigs and travelled to Hamburg with McCartney's girlfriend at the time to visit him.[130] Lennon, jealous by nature, eventually grew possessive and often terrified Powell with his anger and physical violence.[131] In one of his last major interviews Lennon said that until he met Ono, he had never questioned his chauvinistic attitude to women. The Beatles' song "Getting Better", he said, told his own story: "All that 'I used to be cruel to my woman, I beat her and kept her apart from the things that she loved' was me. I used to be cruel to my woman, and physically—any woman. I was a hitter. I couldn't express myself and I hit. I fought men and I hit women. That is why I am always on about peace".[13]

Recalling his reaction in July 1962 on learning that Cynthia was pregnant, Lennon said, "There's only one thing for it Cyn. We'll have to get married."[132] Cynthia told him not to feel obliged, to which he replied, "Neither of us planned to have a baby Cyn, but I love you and I'm not going to leave you now."[132] The couple were married on 23 August at the Mount Pleasant Register Office in Liverpool, with Beatles manager Brian Epstein as best man. His marriage began just as Beatlemania took hold across the UK. He performed in the evening of his wedding day, and would continue to do so almost daily from then on.[133] Epstein, fearing that fans would be alienated by the idea of a married Beatle, asked the Lennons keep their marriage secret. Cynthia complied by telling anyone who asked that her name was Phyllis McKenzie and she had never heard of Lennon. Julian was born on 8 April 1963; Lennon was on tour at the time and did not see his son until three days later.[134]

Cynthia attributes the start of the marriage breakdown to LSD. As a result, she felt that he slowly lost interest in her.[135] When the group travelled by train to Bangor, Wales, in 1967, for the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's Transcendental Meditation seminar, a policeman did not recognise her and stopped her from boarding, so the train left without her. She recalled how, though knowing she could easily get there by other means, the incident seemed to symbolize the ending of their marriage.[136]

After arriving home at Kenwood, and finding Lennon with Ono, Cynthia left the house to stay with friends. Alexis Mardas later claimed to have slept with her that night, and a few weeks later he informed her that Lennon was seeking a divorce and custody of Julian on grounds of her adultery, to which Mardas said he would bear witness. After negotiation, Lennon capitulated and agreed to her divorcing him on the same grounds. The case was settled out of court, Lennon giving her £100,000,[137] roughly one month's earnings for him at the time, along with £2,400 annually, custody of Julian, and ownership of their home.[citation needed]

Brian Epstein

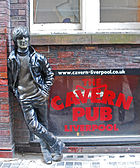

Lennon met Brian Epstein when the Beatles were performing at Liverpool's Cavern Club in 1962. A record store manager, Epstein was homosexual, at a time of strong and widespread social prejudice against homosexuality. According to biographer Philip Norman, one of his reasons for wanting to manage the group was because he was physically attracted to Lennon. Almost as soon as Julian was born, Lennon went on holiday to Spain with Epstein, leading to speculation about their relationship. Questioned about it later, Lennon said, "Well, it was almost a love affair, but not quite. It was never consummated. But it was a pretty intense relationship. It was my first experience with a homosexual that I was conscious was homosexual. We used to sit in a cafe in Torremolinos looking at all the boys and I'd say, 'Do you like that one? Do you like this one?' I was rather enjoying the experience, thinking like a writer all the time: I am experiencing this."[138] Soon after their return from Spain, at McCartney's twenty-first birthday party in June 1963, Lennon physically attacked Cavern Club MC Bob Wooler for saying "How was your honeymoon, John?" The MC, known for his wordplay and affectionate but cutting remarks, was making a joke,[139] but ten months had passed since Lennon's marriage, and the honeymoon, deferred, was still two months in the future.[140] To Lennon, who was intoxicated with alcohol at the time, the matter was simple: "He called me a queer so I battered his bloody ribs in".[141] In 1991, a fictionalised account of the Lennon/Epstein holiday was made into the independent movie The Hours And Times.[142]

Lennon delighted in mocking Epstein for his homosexuality and for the fact that he was Jewish.[143] When Epstein invited suggestions for the title of his autobiography, Lennon offered Queer Jew; on learning of the eventual title, A Cellarful of Noise, he parodied, "More like A Cellarful of Boys".[144] He demanded of a visitor to Epstein's flat, "Have you come to blackmail him? If not, you're the only bugger in London who hasn't."[143] During the recording of "Baby, You're a Rich Man", he sang altered choruses of "Baby, you're a rich fag Jew".[145][146]

Julian Lennon

Lennon's first son Julian was born as his commitments with the Beatles intensified at the height of Beatlemania during his marriage to Cynthia. Lennon was touring with the Beatles when Julian was born on 8 April 1963. Julian's birth, like his mother Cynthia's marriage to Lennon, was kept secret because Epstein was convinced public knowledge of such things would threaten the Beatles' commercial success. Julian recalls how some four years later, as a small child in Weybridge, "I was trundled home from school and came walking up with one of my watercolour paintings. It was just a bunch of stars and this blonde girl I knew at school. And Dad said, 'What's this?' I said, 'It's Lucy in the sky with diamonds.'"[147] Lennon used it as the title of a Beatles' song, and though it was later reported to have been derived from the initials LSD, Lennon insisted, "It's not an acid song."[148] McCartney corroborated Lennon's explanation that Julian innocently came up with the name.[148] Lennon was distant from Julian, who felt closer to McCartney than to his father. During a car journey to visit Cynthia and Julian during Lennon's divorce, McCartney composed a song, "Hey Jules", to comfort him. It would evolve into the Beatles song "Hey Jude". Lennon later said, "That's his best song. It started off as a song about my son Julian ... he turned it into 'Hey Jude'. I always thought it was about me and Yoko but he said it wasn't."[149]

Lennon's relationship with Julian was already strained, and after Lennon and Ono's 1971 move to New York, Julian would not see his father again until 1973.[150] With Pang's encouragement, it was arranged for him (and his mother) to visit Lennon in Los Angeles, where they went to Disneyland.[151] Julian started to see his father regularly, and Lennon gave him a drumming part on a Walls and Bridges track.[152] He bought Julian a Gibson Les Paul guitar and other instruments, and encouraged his interest in music by demonstrating guitar chord techniques.[152] Julian recalls that he and his father "got on a great deal better" during the time he spent in New York: "We had a lot of fun, laughed a lot and had a great time in general."[153]

In a Playboy interview with David Sheff shortly before his death, Lennon said, "Sean was a planned child, and therein lies the difference. I don't love Julian any less as a child. He's still my son, whether he came from a bottle of whiskey or because they didn't have pills in those days. He's here, he belongs to me, and he always will." He said he was trying to re-establish a connection with the then 17-year-old, and confidently predicted, "Julian and I will have a relationship in the future."[13] After his death it was revealed that he had left Julian very little in his will.[154]

Yoko Ono

Two versions exist of how Lennon met Ono. According to the first, on 9 November 1966 Lennon went to the Indica gallery in London, where Ono was preparing her conceptual art exhibit, and they were introduced by gallery owner John Dunbar.[155] Lennon was intrigued by Ono's "Hammer A Nail": patrons hammered a nail into a wooden board, creating the art piece. Although the exhibition had not yet begun, Lennon wanted to hammer a nail into the clean board, but Ono stopped him. Dunbar asked her, "Don't you know who this is? He's a millionaire! He might buy it." Ono had supposedly not heard of the Beatles, but relented on condition that Lennon pay her five shillings, to which Lennon replied, "I'll give you an imaginary five shillings and hammer an imaginary nail in."[13] The second version, told by McCartney, is that in late 1965, Ono was in London compiling original musical scores for a book John Cage was working on, Notations, but McCartney declined to give her any of his own manuscripts for the book, suggesting that Lennon might oblige. When asked, Lennon gave Ono the original handwritten lyrics to "The Word".[156]

Ono began telephoning and calling at Lennon's home, and when his wife asked for an explanation, he explained that Ono was only trying to obtain money for her "avant-garde bullshit".[157] In May 1968, while his wife was on holiday in Greece, Lennon invited Ono to visit. They spent the night recording what would become the Two Virgins album, after which, he said, they "made love at dawn."[158] When Lennon's wife returned home she found Ono wearing her bathrobe and drinking tea with Lennon who simply said, "Oh, hi."[159] Ono became pregnant in 1968 and miscarried a male child they named John Ono Lennon II on 21 November 1968,[125] a few weeks after Lennon's divorce from Cynthia was granted.[160]

During Lennon's last two years in the Beatles, he and Ono began public protests against the Vietnam War. They were married in Gibraltar on 20 March 1969, and spent their honeymoon in Amsterdam campaigning with a week-long Bed-In for peace. They planned another Bed-In in the United States, but were denied entry,[citation needed] so held one instead at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, where they recorded "Give Peace a Chance".[161] They often combined advocacy with performance art, as in their "Bagism", first introduced during a Vienna press conference. Lennon detailed this period in the Beatles' song "The Ballad of John and Yoko".[162] Lennon changed his name by deed poll on 22 April 1969, adding "Ono" as a middle name. The brief ceremony took place on the roof of the Apple Corps building, made famous three months earlier by the Beatles' Let It Be rooftop concert. Although he used the name John Ono Lennon thereafter, official documents referred to him as John Winston Ono Lennon, since he was not permitted to revoke a name given at birth.[163] After Ono was injured in a car accident, Lennon arranged for a king-sized bed to be brought to the recording studio as he worked on the Beatles' last album, Abbey Road.[164] To escape the acrimony of the band's break-up, Ono suggested they move permanently to New York, which they did on 31 August 1971. They first lived in the St. Regis Hotel on 5th Avenue, East 55th Street, then moved to a street-level flat at 105 Bank Street, Greenwich Village, on 16 October 1971. After a robbery, they relocated to the more secure Dakota at 1 West 72nd Street, in May 1973.[citation needed] In a 1981 interview, Ono light-heartedly remarked, "I used to say [to Lennon], 'I think you’re a closet fag, you know.' Because after we started to live together, John would say to me, 'Do you know why I like you? Because you look like a bloke in drag.'"[165]

According to author Albert Goldman, Ono was regarded by Lennon as an "almost magical being" who could solve all his problems for him, but this was a "grand illusion",[166] and she openly cheated on him with gigolos.[167] Eventually, writes Goldman, "both he and Yoko were burnt out from years of hard drugs, overwork, emotional breakdowns, quack cures, and bizarre diets, to say nothing of the effects of living constantly in the glare of the mass media."[168] After their separation, "no longer collaborating as a team, they remained in constant communication. ... No longer able to live together, they found that they couldn’t live apart either."[169]

May Pang and the "lost weekend"

ABKCO Industries, formed in 1968 by Allen Klein as an umbrella company to ABKCO Records, recruited May Pang as a receptionist in 1969. Through involvement in a project with ABKCO, Lennon and Ono met her the following year. She became their personal assistant. After she had been working with the couple for three years, Ono confided that she and Lennon were becoming estranged from one another. She went on to suggest that Pang should begin a physical relationship with Lennon, telling her, "He likes you a lot." Pang, 22, astounded by Ono's proposition, eventually agreed to become Lennon's companion. The pair soon moved to California, beginning an eighteen-month period he later called his "lost weekend".[104] In Los Angeles, Pang encouraged Lennon to develop regular contact with Julian, whom he had not seen for two years. He also rekindled friendships with Starr, McCartney, Beatles roadie Mal Evans, and Harry Nilsson.

When Lennon decided to produce Nilsson's album Pussy Cats, Pang rented a beach house for all the musicians.[170] Together, Lennon and Nilsson soon began to indulge in alcoholic excesses, and their drunken antics became fodder for the tabloids. Two widely publicised incidents occurred at The Troubadour club in March 1974, the first when Lennon placed a Kotex on his forehead and scuffled with a waitress, and the second, two weeks later, when Lennon and Nilsson were ejected from the same club after heckling the Smothers Brothers.[171] On another occasion, after misunderstanding something Pang said, Lennon attempted to strangle her, only relenting when physically restrained by Nilsson.[172] Lennon returned to New York with Pang in June 1974 to finish work on Pussy Cats and record his own Walls and Bridges. They "prepared a spare room" in their newly rented apartment for Julian to visit.[172] Lennon, hitherto inhibited by Ono in this regard, began to reestablish contact with other relatives and friends. By December he and Pang were considering a house purchase, and he was refusing to accept Ono's telephone calls. In January 1975, he agreed to meet Ono—who said she had found a cure for smoking—but after the meeting failed to return home or call Pang. When Pang telephoned the next day, Ono told her Lennon was unavailable, being exhausted after a hypnotherapy session. Two days later, Lennon reappeared at a joint dental appointment, stupefied and confused to such an extent that Pang believed he had been brainwashed. He told her his separation from Ono was now over, though Ono would allow him to continue seeing her, as his mistress, which he did.[173]

In 1975, Lennon told Bob Harris on The Old Grey Whistle Test, "We had a lot of fun. It was Keith Moon, Harry, me, Ringo all living together in a house, and we had some moments folks ... but it got a little near the knuckle. I hit the bottle like I was 18 or 19 and I was acting like I was still at college. It was the first night I drank Brandy Alexanders ... I was with Harry Nilsson, who didn't quite get as much coverage as me."[136]

Sean Lennon

When Lennon and Ono were reunited, she became pregnant, but having previously suffered three miscarriages in her attempt to have a child with Lennon, she said she wanted an abortion. She agreed to allow the pregnancy to continue on condition that Lennon adopt the role of househusband; this he agreed to do.[174] Sean was born on 9 October 1975, Lennon's 35th birthday, delivered by Caesarean section. Lennon's subsequent career break would span five years. He had a photographer take pictures of Sean every day of his first year, and created numerous drawings for him, posthumously published as Real Love: The Drawings for Sean. Lennon later proudly declared, "He didn't come out of my belly but, by God, I made his bones, because I've attended to every meal, and to how he sleeps, and to the fact that he swims like a fish."[175]

Former Beatles

Although his friendship with Ringo Starr remained consistently warm during the years following the Beatles' break-up in 1970, Lennon's relationship with McCartney and Harrison varied. He was close to Harrison initially, but the two drifted apart after Lennon moved to America. When Harrison was in New York for his December 1974 Dark Horse tour, Lennon agreed to join him on stage, but failed to appear after an argument over Lennon's refusal to sign an agreement that would finally dissolve the Beatles' legal partnership. (Lennon eventually signed the papers in Walt Disney World in Florida, while on holiday there with Pang and Julian.[176]) Harrison incensed Lennon in 1980 when he published an autobiography that made very little mention of him. Lennon told Playboy, "I was hurt by it. By glaring omission ... my influence on his life is absolutely zilch and nil ... he remembers every two-bit sax player or guitarist he met in subsequent years. I'm not in the book."[177]

Lennon's most intense feelings were reserved for McCartney. In addition to attacking him through the lyrics of "How Do You Sleep?", Lennon argued with him through the press for three years after the group split. The two later began to reestablish something of the close friendship they had once known, and in 1974 even played music together again for what would be the one and only time (see A Toot and a Snore in '74), before growing apart once more. Lennon said that during McCartney's final visit, in April 1976, they watched the episode of Saturday Night Live in which Lorne Michaels made a $3,000 cash offer to get the Beatles to reunite on the show.[178] The pair considered going to the studio to make a joke appearance, attempting to claim their share of the money, but were too tired.[13] The event was fictionalised in the television film Two of Us (2000).[178]

Along with his estrangement from McCartney, Lennon always felt a musical competitiveness with him and kept an ear on his music. During his five-year career break he was content to sit back so long as McCartney was producing what Lennon saw as mediocre "product."[179] When McCartney released "Coming Up" in 1980, the year Lennon returned to the studio and the last year of his life, he took notice. "It's driving me crackers!" he jokingly complained, because he couldn't get the tune out of his head.[179] Asked the same year whether the group were dreaded enemies or the best of friends, he replied that they were neither, and that he had not seen any of them in a long time. But he also said, "I still love those guys. The Beatles are over, but John, Paul, George and Ringo go on."[13]

Political activism

Anti-war and civil rights activities

Lennon and Ono used their honeymoon as a Bed-In for Peace at the Amsterdam Hilton. The March 1969 event attracted worldwide media coverage, as did a second Bed-In three months later at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal.[180] Recorded during the second Bed-In, and quickly taken up as an antiwar anthem, "Give Peace a Chance" was sung by a quarter of a million demonstrators against the Vietnam War in Washington, DC, on 15 October, the second Vietnam Moratorium Day.[76][181]

Later that year, Lennon and Ono supported efforts by the family of James Hanratty, hanged for murder in 1962, to prove his innocence.[182] Those who had condemned Hanratty were, according to Lennon, "the same people who are running guns to South Africa and killing blacks in the streets. ... The same bastards are in control, the same people are running everything, it's the whole bullshit bourgeois scene."[183] In London, Lennon and Ono staged a "Britain Murdered Hanratty" banner march and a "Silent Protest For James Hanratty",[74] and produced a 40-minute documentary on the case. At an appeal hearing years later, Hanratty's conviction was upheld.[184]

Lennon and Ono showed their solidarity with the Clydeside UCS workers' work-in of 1971 by sending a bouquet of red roses and a cheque for £5,000.[185] On moving to New York City in August that year, they befriended two of the Chicago Seven, Yippie anti-war activists Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman.[186] Another anti-war activist, John Sinclair, poet and co-founder of the White Panther Party, was serving ten years in the state prison for selling two joints of marijuana after a series of previous convictions for possession of the drug.[187] At the "Free John Sinclair" concert in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on 10 December 1971, Lennon and Ono appeared on stage with David Peel, Phil Ochs, Stevie Wonder, Bob Seger and other musicians, as well as Rubin and Bobby Seale of the Black Panther Party.[188] Lennon, through his newly written song "John Sinclair", called on the authorities to "Let him be, set him free, let him be like you and me." Some 20,000 people were present at the rally, and less than three days later the State of Michigan released Sinclair from prison.[189] The performance was recorded, and later appeared on John Lennon Anthology (1998).

Following the Bloody Sunday massacre in 1972, in which 27 civil rights protesters were shot by the British Army during a Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association march, Lennon said that given the choice between the army and the IRA he would side with the latter, and in 2000, a former member of Britain's domestic security service MI5 suggested that Lennon had given money to the IRA.[190] Biographer Bill Harry records that following Bloody Sunday, Lennon and Ono financially supported the production of the film The Irish Tapes, a political documentary with a pro-IRA slant.[191] According to FBI surveillance reports, Lennon was sympathetic to Tariq Ali's International Marxist Group; Ali, writing for The Guardian in 2006, called this "accurate".[192]

Deportation attempt

Following the impact of "Give Peace a Chance" and "Happy Xmas (War is Over)", both strongly associated with the anti-Vietnam-War movement, the Nixon administration, hearing rumours of Lennon's involvement in a concert to be held in San Diego at the same time as the Republican National Convention,[193] tried to have him deported. Nixon believed that Lennon's anti-war activities could cost him his re-election;[194] Republican Senator Strom Thurmond suggested in a February 1972 memo that "deportation would be a strategic counter-measure" against Lennon.[195] The next month the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) began deportation proceedings, arguing that his 1968 misdemeanor conviction for cannabis possession in London had made him ineligible for admission to the United States. Lennon spent the next three and a half years in and out of deportation hearings until on 8 October 1975, when a court of appeals barred the deportation attempt, stating " ... the courts will not condone selective deportation based upon secret political grounds."[196][99] While the legal battle continued, Lennon attended rallies and made television appearances. Lennon and Ono co-hosted the Mike Douglas Show for a week in February 1972, introducing guests such as Jerry Rubin and Bobby Seale to mid-America.[197] In 1972, Bob Dylan wrote a letter to the INS defending Lennon, stating:

John and Yoko add a great voice and drive to the country’s so-called art institution. They inspire and transcend and stimulate and by doing so, only help others to see pure light and in doing that, put an end to this dull taste of petty commercialism which is being passed off as Artist Art by the overpowering mass media. Hurray for John and Yoko. Let them stay and live here and breathe. The country’s got plenty of room and space. Let John and Yoko stay![198][199]

On 23 March 1973, Lennon was ordered to leave the US within 60 days.[200] Ono, meanwhile, was granted permanent residence. In response, Lennon and Ono held a press conference on 1 April 1973 at the New York chapter of the American Bar Association, where they announced the formation of the state of Nutopia; a place with "no land, no boundaries, no passports, only people".[201] Waving the white flag of Nutopia (two handkerchiefs), they asked for political asylum in the US. The press conference was filmed, and would later appear in the 2006 documentary The U.S. vs. John Lennon.[202] Lennon's Mind Games (1973) included the track "Nutopian International Anthem", which comprised three seconds of silence.[203] Soon after the press conference, Nixon's involvement in a political scandal came to light, and in June the Watergate hearings began in Washington, DC. They led to the president's resignation 14 months later. Nixon's successor, Gerald Ford, showed little interest in continuing the battle against Lennon, and the deportation order was overturned in 1975. The following year, his US immigration status finally resolved, Lennon received his "green card" certifying his permanent residency, and when Jimmy Carter was inaugurated as president in January 1977, Lennon and Ono attended the Inaugural Ball.[204]

FBI surveillance and declassified documents

After Lennon's death, historian Jon Wiener filed a Freedom of Information Act request for FBI files documenting the Bureau's role in the deportation attempt.[205] The FBI admitted it had 281 pages of files on Lennon, but refused to release most of them on the grounds that they contained national security information. In 1983, Wiener sued the FBI with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. It took 14 years of litigation to force the FBI to release the withheld pages.[206] The ACLU, representing Wiener, won a favourable decision in their suit against the FBI in the Ninth Circuit in 1991.[207] The Justice Department appealed the decision to the Supreme Court in April 1992, but the court declined to review the case.[208] In 1997, respecting President Bill Clinton's newly instigated rule that documents should be withheld only if releasing them would involve "foreseeable harm", the Justice Department settled most of the outstanding issues outside court by releasing all but 10 of the contested documents.[208] Wiener published the results of his 14-year campaign in January 2000. Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files contained facsimiles of the documents, including "lengthy reports by confidential informants detailing the daily lives of anti-war activists, memos to the White House, transcripts of TV shows on which Lennon appeared, and a proposal that Lennon be arrested by local police on drug charges".[209] The story is told in the documentary The U.S. vs. John Lennon. The final 10 documents in Lennon's FBI file, which reported on his ties with London anti-war activists in 1971 and had been withheld as containing "national security information provided by a foreign government under an explicit promise of confidentiality", were released in December 2006. They contained no indication that the British government had regarded Lennon as a serious threat; one example of the released material was a report that two prominent British leftists had hoped Lennon would finance a left-wing bookshop and reading room.[210]

Writing and art

Lennon's biographer Bill Harry writes that Lennon began drawing and writing creatively at an early age with the encouragement of his uncle. He collected his stories, poetry, cartoons, and caricatures in a Quarry Bank High School exercise book that he called the Daily Howl. The drawings were often of crippled people, and the writings satirical, and throughout the book was an abundance of wordplay. According to classmate Bill Turner, Lennon created the Daily Howl to amuse his best friend and later Quarrymen band mate, Pete Shotton, to whom he would show his work before he let anyone else see it. Turner said that Lennon "had an obsession for Wigan Pier. It kept cropping up", and in Lennon's story A Carrot In A Potato Mine, "the mine was at the end of Wigan Pier." Turner described how one of Lennon's cartoons depicted a bus stop sign annotated with the question, "Why?". Above was a flying pancake, and below, "a blind man wearing glasses leading along a blind dog—also wearing glasses".[211]

Lennon's love of wordplay and nonsense with a twist found a wider audience when he was 24. Harry writes that In His Own Write (1964) was published after "Some journalist who was hanging around the Beatles came to me and I ended up showing him the stuff. They said, 'Write a book' and that's how the first one came about". Like the Daily Howl it contained a mix of formats including short stories, poetry, plays and drawings. One story, "Good Dog Nigel", tells the tale of "a happy dog, urinating on a lamp post, barking, wagging his tail—until he suddenly hears a message that he will be killed at three o'clock." The Times Literary Supplement considered the poems and stories "remarkable ... also very funny ... the nonsense runs on, words and images prompting one another in a chain of pure fantasy". The review concluded, "It is worth the attention of anyone who fears for the impoverishment of the English language and British imagination ... humorists have done more to preserve and enrich these assets than most serious critics allow. Theirs is arguably our liveliest stream of 'experimental writing' ... Lennon shows himself well equipped to take it farther." Book Week reported, "This is nonsense writing, but one has only to review the literature of nonsense to see how well Lennon has brought it off. While some of his homonyms are gratuitous word play, many others have not only double meaning but a double edge." Lennon was surprised by the positive reception: "To my amazement the reviewers liked it ... I didn't think the book would even get reviewed ... I didn't think people would accept the book like they did. To tell you the truth they took the book more seriously than I did myself. It just began as a laugh for me."[212]

In combination with A Spaniard in the Works (1965), In His Own Write formed the basis of the stage play The John Lennon Play: In His Own Write, co-adapted by Victor Spinetti and Adrienne Kennedy. After negotiations between Lennon, Spinetti and the artistic director of the National Theatre, Sir Laurence Olivier, the play opened at the Old Vic in 1968. Lennon and Ono attended the opening night performance, their second public appearance together to date.[213] After Lennon's death, further works were published, including Skywriting by Word of Mouth (1986); Ai: Japan Through John Lennon's Eyes: A Personal Sketchbook (1992), with Lennon's illustrations of the definitions of Japanese words; and Real Love: The Drawings for Sean (1999). The Beatles Anthology (2000) also presented examples of his writings and drawings.

Musicianship

Instruments played

His playing of a mouth organ during a bus journey to visit his cousin in Scotland caught the driver's ear. Impressed, the driver told Lennon of a harmonica he could have if he came to Edinburgh the following day, where one had been stored in the bus depot since a passenger left it on a bus.[214] The professional instrument quickly replaced Lennon's toy. He would continue to play harmonica, often using the instrument during the Beatles' Hamburg years, and it became a signature sound in the group's early recordings. His mother taught him how to play the banjo, later buying him an acoustic guitar. At 16, he played rhythm guitar with the Quarrymen.[215] As his career progressed, he played a variety of electric guitars, predominantly the Rickenbacker 325, Epiphone Casino and Gibson J-160E, and, from the start of his solo career, the Gibson Les Paul Junior.[216][217] Occasionally he played a six-string bass guitar, the Fender Bass VI, providing bass on some Beatles numbers that occupied McCartney with another instrument.[218] His other instrument of choice was the piano, on which he composed many songs, including "Imagine", described as his best-known solo work.[219] His jamming on a piano with McCartney in 1963 led to the creation of the Beatles' first US number one, "I Want to Hold Your Hand".[220] In 1964, he became one of the first British musicians to acquire a Mellotron keyboard, though it was not heard on a Beatles recording until "Strawberry Fields Forever" in late 1966.[221]

Vocal style

When Lennon recorded "Twist and Shout", the final track during the mammoth one-day session that captured the band's 1963 debut album Please Please Me, his voice, already compromised by a cold, came close to giving out. Lennon said, "I couldn't sing the damn thing, I was just screaming."[222] In the words of biographer Barry Miles, "Lennon simply shredded his vocal cords in the interests of rock 'n' roll."[223] The Beatles' producer, George Martin, tells how Lennon "had an inborn dislike of his own voice which I could never understand. He was always saying to me: 'DO something with my voice! ... put something on it ... Make it different.'"[224] Martin obliged, often using double-tracking and other techniques. Music critic Robert Christgau says that Lennon's "greatest vocal performance ... from scream to whine, is modulated electronically ... echoed, filtered, and double tracked."[225]

As his Beatles era segued into his solo career, his singing voice found a widening range of expression. Biographer Chris Gregory writes that Lennon was, "tentatively beginning to expose his insecurities in a number of acoustic-led 'confessional' ballads, so beginning the process of 'public therapy' that will eventually culminate in the primal screams of 'Cold Turkey' and the cathartic John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band."[226] David Stuart Ryan notes Lennon's vocal delivery to range from, "extreme vulnerability, sensitivity and even naivety" to a hard "rasping" style.[227] Wiener too describes contrasts, saying the singer's voice can be "at first subdued; soon it almost cracks with despair"[228] Music historian Ben Urish recalls hearing the Beatles' Ed Sullivan Show performance of "This Boy" played on the radio a few days after Lennon's murder: "As Lennon's vocals reached their peak ... it hurt too much to hear him scream with such anguish and emotion. But it was my emotions I heard in his voice. Just like I always had."[229]

Legacy

Music historians Schinder and Schwartz, writing of the transformation in popular music styles that took place between the 1950s and the 1960s, say that the Beatles' influence cannot be overstated: having "revolutionized the sound, style, and attitude of popular music and opened rock and roll's doors to a tidal wave of British rock acts", the group then "spent the rest of the 1960s expanding rock's stylistic frontiers".[230] Liam Gallagher, his group Oasis among the many who acknowledge the band's influence, identifies Lennon as a hero; in 1999 he named his first child Lennon Gallagher in tribute.[231] On National Poetry Day in 1999, after conducting a poll to identify the UK's favourite song lyric, the BBC announced "Imagine" the winner.[232]

In a 2006 Guardian article, Jon Wiener wrote: "For young people in 1972, it was thrilling to see Lennon's courage in standing up to [US President] Nixon. That willingness to take risks with his career, and his life, is one reason why people still admire him today."[233] Whilst for music historians Urish and Bielen, Lennon's most significant effort was "the self-portraits ... in his songs [which] spoke to, for, and about, the human condition."[234]

Lennon continues to be mourned throughout the world and has been the subject of numerous memorials and tributes. In 2010, on what would have been Lennon’s 70th birthday, the John Lennon Peace Monument was unveiled in Chavasse Park, Liverpool, by Cynthia and Julian Lennon.[235] The sculpture entitled ‘Peace & Harmony’ exhibits peace symbols and carries the inscription “Peace on Earth for the Conservation of Life · In Honour of John Lennon 1940 – 1980”.

Awards and sales

The Lennon/McCartney songwriting partnership is regarded as one of the most influential and successful of the 20th century.[236] As performer, writer or co-writer Lennon has had 27 number one singles on the US Hot 100 chart.a His album sales in the US stand at 14 million units.[237] Double Fantasy, released shortly before his death, and his best-selling, post-Beatles studio album[238] at three million shipments in the US,[239] won the 1981 Grammy Award for Album of the Year.[240] The following year, the BRIT Award for Outstanding Contribution to Music went to Lennon.[241] Participants in a 2002 BBC poll voted him eighth of "100 Greatest Britons".[242] Between 2003 and 2008, Rolling Stone recognised Lennon in several reviews of artists and music, ranking him fifth of "100 Greatest Singers of All Time"[243] and 38th of "The Immortals: The Fifty Greatest Artists of All Time",[244] and his albums John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band and Imagine, 22nd and 76th respectively of "The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time".[244][245] He was appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) with the other Beatles in 1965.[48] He was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1987[246] and into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994.[103]

Discography

- Unfinished Music No.1: Two Virgins (with Yoko Ono) (1968)

- Unfinished Music No.2: Life with the Lions (with Yoko Ono) (1969)

- Wedding Album (with Yoko Ono) (1969)

- John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970)

- Imagine (1971)

- Some Time in New York City (with Yoko Ono) (1972)

- Mind Games (1973)

- Walls and Bridges (1974)

- Rock 'n' Roll (1975)

- Double Fantasy (with Yoko Ono) (1980)

- Milk and Honey (with Yoko Ono) (1984)

- Menlove Ave. (1986)

Notes

^ Note a: Lennon was responsible for 27 Billboard Hot 100 number one singles as performer, writer or co-writer.

- Solo (3): "Whatever Gets You Thru the Night", "(Just Like) Starting Over", "Imagine".[247]

- With David Bowie (1): "Fame".[248]

- With The Beatles (21): "Can't Buy Me Love", "I Feel Fine", "I Want to Hold Your Hand", "Love Me Do", "She Loves You", "A Hard Day's Night", "Eight Days a Week", "Help!", "Ticket to Ride", "Yesterday", "Paperback Writer", "We Can Work It Out", "All You Need Is Love", "Hello Goodbye", "Penny Lane", "Hey Jude", "Come Together", "Get Back", "For You Blue", "Let It Be", "The Long and Winding Road".[249]

- As co-writer of releases by other artists (2): "A World Without Love" (Peter and Gordon),[250] "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" (Elton John).[251]

Citations

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 504.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 24.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 54.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 27.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 42.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 497.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 55.

- ^ a b Spitz 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sheff 1981.

- ^ Harry 2009.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 702.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 819.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 411.

- ^ Spitz 2005, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 40.

- ^ ClassReports 2008.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 45.

- ^ Norman 2009, p. 89.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 48.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 553–555.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 738.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 95.

- ^ Spitz 2005, pp. 93–99.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 44.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 32.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 47, 50.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 56.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 53.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 57.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 67.

- ^ Frankel 2007.

- ^ Lennon 2005, pp. 91–94.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 93.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 721.

- ^ Doggett 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Shennan 2007.

- ^ Coleman 1984a, pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b London Gazette 1965, p. 5488.

- ^ Coleman 1984a, p. 288.

- ^ Gould 2008, p. 268.

- ^ Lawrence 2005, p. 62.

- ^ The Beatles 2000, p. 171.

- ^ a b Harry 2000b, p. 570.

- ^ Cleave 2007.

- ^ Gould 2008, pp. 5–6, 249, 281, 347.

- ^ Brown 1983, p. 222.

- ^ Gould 2008, p. 319.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 281.

- ^ Time 1967.

- ^ BBC News 2007b.

- ^ Brown 1983, p. 276.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 397.

- ^ Hoppa 2010.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 349-373.

- ^ Logan 1967.

- ^ Lewisohn 1988, p. 131.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 31.

- ^ TelegraphKlein 2010.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 276–278.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 774–775.

- ^ Fawcett 1976, p. 185.

- ^ Coleman 1984a, p. 279.

- ^ Coleman 1984a, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Miles and Badman 2003.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 615–617.

- ^ a b Perone 2001, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Edmondson 2010, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Spitz 2005, pp. 853–54.

- ^ Loker 2009, p. 348.

- ^ Wenner 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Wenner 2000, p. 24.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 408–410.

- ^ Blaney 2005, p. 56.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 640–641.

- ^ Riley 2002, p. 375.

- ^ Schechter 1997, p. 106.

- ^ Wiener 1990, p. 157.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 382.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 382–383.

- ^ Gerson 1971.

- ^ Vigilla 2005.

- ^ Goodman 1984.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 354–356.

- ^ Peebles 1981, p. 44.

- ^ Allmusic 2010f.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 960.

- ^ Wiener 1990, p. 204.

- ^ a b c BBC News 2006a.

- ^ a b Landau 1974.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 979–980.

- ^ Deming 2008.

- ^ a b The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum 1994.

- ^ a b Harry 2000b, pp. 698–699.

- ^ The Very Best of Mick Jagger liner notes

- ^ Badman 2001, 1974.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 284.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 970.

- ^ The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum 1996.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 240, 563.

- ^ a b Harry 2000b, p. 758.

- ^ Badman 2001, 1975.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 553.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 166.

- ^ Bennahum 1991, p. 87.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 814.

- ^ BBC News 2006b.

- ^ Schinder & Schwartz 2007, p. 178.

- ^ Clarke Jr. 2007.

- ^ Ginell 2009.

- ^ Badman 2001, 1980.

- ^ Ingham 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 145.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 692.

- ^ a b Harry 2000b, pp. 510. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEHarry2000b510" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ CNN.com 2004.

- ^ BBC News 2010a.

- ^ Lennon 2005, pp. 17–23.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Lennon 2005, pp. 89–95.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 492–493.

- ^ a b Lennon 2005, p. 91.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 493–495.

- ^ Lennon 2005, p. 113.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 496–497.

- ^ a b Warner Brothers 1988.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 498.

- ^ Harry 2000a, p. 232.

- ^ Harry 2000a, pp. 1165, 1169.

- ^ Lennon 2005, pp. 94, 119–120.

- ^ Harry 2000a, p. 1169.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 353–354.

- ^ a b Harry 2000b, p. 232.

- ^ Coleman 1992, pp. 298–299.

- ^ Norman 2008, p. 503.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 206.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 517.

- ^ a b Harry 2000b, p. 574.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 341.

- ^ Pang 2008, back cover.

- ^ Lennon 2005, pp. 252–255.

- ^ a b Lennon 2005, p. 258.

- ^ Times Online 2009.

- ^ Badman 2003, p. 393.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 682.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 272.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 683.

- ^ Two Virgins liner notes

- ^ Lennon 1978, p. 183.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 800.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 276.

- ^ Coleman 1992, p. 550.

- ^ Coleman 1984b, p. 64.

- ^ Emerick & Massey 2006, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Norman 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Goldman 2001, p. 281.

- ^ Goldman 2001, p. 663.

- ^ Goldman 2001, p. 458.

- ^ Blaney 2005, p. 139.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 735.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 927–929.

- ^ a b Harry 2000b, p. 700.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 700–701.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 535, 690.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 535.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 195.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 327.

- ^ a b Harry 2000b, pp. 934–935.

- ^ a b Seaman 1991, p. 122.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 745–748.

- ^ Holsinger 1999, p. 389.

- ^ Wenner 2000, p. 43.

- ^ Clark 2002.

- ^ Milmo 2002.

- ^ McGinty 2010.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 344.

- ^ Buchanan 2009.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 789–790, 812–813.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 813.

- ^ Bright 2000.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 403.

- ^ Ali 2006.

- ^ Wiener 1999, p. 2.

- ^ BBC News 2000.

- ^ Wiener 1990, p. 225.

- ^ Coleman 1992, pp. 576–583.

- ^ BBC News 2006c.

- ^ Wiener, Jon. "Bob Dylan's defense of John Lennon". The Nation, 8 October 2010

- ^ Photo Copy of Bob Dylan's 1972 Letter to the INS in Defense of John Lennon

- ^ Wiener 1999, p. 326.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 663.

- ^ Urish & Bielen 2007, p. 143.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 664.

- ^ Coleman 1984a, p. 289.

- ^ Wiener 1999, p. 13.

- ^ John S. Friedman 2005, p. 252.

- ^ Wiener 1999, p. 315.

- ^ a b Wiener 1999, pp. 52–54, 76.

- ^ Wiener 1999, p. 27.

- ^ The Associated Press 2006.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 393–394.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 396–397.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 313.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 738–740.

- ^ Prown and Newquist 2003, p. 213.

- ^ Lawrence 2009, p. 27.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 297.

- ^ Blaney 2005, p. 83.

- ^ Everett 2001, p. 200.

- ^ Babiuk 2002, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Wenner 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Miles and Badman 2003, p. 90.

- ^ Coleman 1992, pp. 369–370.

- ^ Wiener 1990, p. 143.

- ^ Gregory 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Ryan 1982, pp. 118, 241.

- ^ Wiener 1990, p. 35.

- ^ Urish & Bielen 2007, p. 123.

- ^ Schinder & Schwartz 2007, p. 160.

- ^ Harry 2000b, p. 265.

- ^ Harry 2000b, pp. 382–383.

- ^ Wiener 2006.

- ^ Urish & Bielen 2007, pp. 121–122.

- ^ The Telegraph. "Monument to John Lennon unveiled in Liverpool on his '70th birthday'".

- ^ BBC News 2005.

- ^ RIAA 2010b.

- ^ Greenberg 2010, p. 202.

- ^ RIAA 2010a.

- ^ grammy.com.

- ^ Brit Awards 2010.

- ^ BBC News 2002.

- ^ Browne 2008.

- ^ a b Rolling Stone 2008.

- ^ Rolling Stone 2003.

- ^ Songwriters Hall of Fame 2009.

- ^ Allmusic 2010a.

- ^ Allmusic 2010e.

- ^ Allmusic 2010b.

- ^ Allmusic 2010d.

- ^ Allmusic 2010c.

References

- Ali, Tariq. The Guardian. John Lennon, the FBI and me; 20 December 2006 [Retrieved 18 August 2010].

- Allmusic. David Bowie – Billboard Singles [Retrieved 13 November 2010].