2011 Egyptian revolution: Difference between revisions

GrouchoBot (talk | contribs) m r2.6.4) (robot Modifying: no:Revolusjonen i Egypt |

Clarify |

||

| Line 359: | Line 359: | ||

| within 6 months |

| within 6 months |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| 3. Dismantling the |

| 3. Dismantling the secret police |

||

| under discussions{{citation needed|date=February 2011}} |

| under discussions{{citation needed|date=February 2011}} |

||

| |

| |

||

Revision as of 21:35, 22 February 2011

| Egyptian Revolution of 2011 | |

|---|---|

Demonstrators at Cairo's Tahrir Square on 8 February 2011 | |

| Date | 25 January 2011 – Ongoing unrest |

| Resulted in | Resignation of President Hosni Mubarak, and the military controlling the Egyptian government. Military promising a civillian government and the lift of the emergency law. Ongoing.[1] |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | at least 384[2][3] including at least 135 protesters, 12 policemen,[4][5][6] 12 escaped prisoners, and one prison chief[7][8] |

| Injuries | 5,500 people[9] |

| Arrested | Over 1,000 as of 26 January[10] |

| This article is part of a series on the |

|

|---|

|

|

| Constitution (history) |

| Political parties (former) |

|

|

The Egyptian Revolution of 2011 (Template:Lang-ar al-Thawrah al-Miṣriyyah sanat 2011) began in Egypt on 25 January 2011, with a series of street demonstrations, marches, rallies, acts of civil disobedience, riots, labour strikes, and violent clashes in Cairo, Alexandria, and throughout other cities in Egypt, following similar events in Tunisia and as part of a longer-term campaign of civil resistance.[11] Millions of protesters from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds and religions[12] demanded the overthrow of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, along with an end to corruption and police repression, and enactment of democratic reforms of the political system.[13] On 11 February, Mubarak resigned from office as a result of determined popular protest and pressure.[14][15]

Grievances of Egyptian protesters have focused on legal and political issues[16] including police brutality,[11] state of emergency laws,[11] lack of free elections and freedom of speech,[17] and uncontrollable corruption,[17] as well as economic issues including high unemployment,[18] food price inflation,[18] and low minimum wages.[11][18] The primary demands from protest organizers are the end of the Hosni Mubarak regime, the end of Emergency Law (martial law), freedom, justice, a responsive non-military government, and management of Egypt's resources.[19] Labour unions were said to play an integral part in the protests.[20]

As of 16 February, at least 365 deaths had been reported, and those injured number in the thousands. The capital city of Cairo was described as "a war zone,"[21] and the port city of Suez has been the scene of frequent violent clashes. The government imposed a curfew that protesters defied and that the police and military did not enforce. The presence of Egypt's Central Security Forces police, loyal to Mubarak, was gradually replaced by largely restrained military troops. In the absence of police, there was looting by gangs that opposition sources said were instigated by plainclothes police officers. In response, civilians self-organised watch groups to protect neighbourhoods.[22][23][24][25][26]

International response to the protests was initially mixed,[27] though most have called for some sort of peaceful protests on both sides and moves toward reform. Mostly Western governments also expressed concern for the situation. Many governments issued travel advisories and began making attempts at evacuating their citizens from the country.[28] The Egyptian Revolution, along with Tunisian events, has influenced demonstrations in other Arab countries including Yemen, Bahrain, Jordan and Libya.

Mubarak dissolved his government and appointed military figure and former head of the Egyptian General Intelligence Directorate Omar Suleiman as Vice-President in an attempt to quell dissent. Mubarak asked aviation minister and former chief of Egypt's Air Force, Ahmed Shafik, to form a new government. Mohamed ElBaradei became a major figure of the opposition, with all major opposition groups supporting his role as a negotiator for some form of transitional unity government.[29] In response to mounting pressure Mubarak announced he would not seek re-election in September.[30]

On 11 February, Vice President Omar Suleiman announced that Mubarak would be stepping down as president and turning power over to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.[31] The junta, headed by effective head of state Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, announced on 13 February that the constitution would be suspended, both houses of parliament dissolved, and that the military would rule for six months until elections could be held. The prior cabinet, including Prime Minister Ahmed Shafik, would continue to serve as a caretaker government until a new one is formed.[32]

Naming

In Egypt and the wider Arab world, the protests and subsequent changes in the government, are mostly called the 25 January Revolution (ثورة 25 يناير Thawrat 25 Yanāyir) and Rage Revolution (ثورة الغضب),and sometimes called [33] the Revolution of the Youth (ثورة الشباب Thawrat al-Shabāb), Lotus Revolution (ثورة اللوتس) or the White Revolution (الثورة البيضاء al-Thawrah al-bayḍāʾ). In the Media it has been known as the "18 Day Revolution".

Background

Hosni Mubarak became head of Egypt's semi-presidential republic government following the assassination of President Anwar El Sadat, and continued to serve until his departure in 2011. Mubarak's 30-year reign made him the longest serving President in Egypt's history.[34] Mubarak and his National Democratic Party (NDP) government maintained one-party rule under a continuous state of emergency since 1981.[35] Mubarak's government earned the support of the West and a continuation of annual aid from the United States by maintaining policies of suppression towards Islamic militants and peace with Israel.[35] Hosni Mubarak was often compared to an Egyptian pharaoh by the media and by some of his harsher critics due to his authoritarian rule.[36]

Emergency law

An emergency law (Law No. 162 of 1958) was enacted after the 1967 Six-Day War, suspended for 18 months in the early 1980s,[37] and continuously in effect since President Sadat's 1981 assassination.[38] Under the law, police powers are extended, constitutional rights suspended, censorship is legalized,[39] and the government may imprison individuals indefinitely and without reason. The law sharply limits any non-governmental political activity, including street demonstrations, non-approved political organizations, and unregistered financial donations.[37] The Mubarak government has cited the threat of terrorism in order to extend the emergency law,[38] claiming that opposition groups like the Muslim Brotherhood could come into power in Egypt if the current government did not forgo parliamentary elections and suppressed the group through actions allowed under emergency law.[40] This has led to the imprisonment of activists without trials,[41] illegal undocumented hidden detention facilities,[42][43] and rejecting university, mosque, and newspaper staff members based on their political inclination.[44] A parliamentary election in December 2010 was preceded by a media crackdown, arrests, candidate bans (particularly of the Muslim Brotherhood), and allegations of fraud involving the near unanimous victory by the ruling party in parliament.[37] Human rights organizations estimate that in 2010 between 5,000 and 10,000 people were in long-term detention without charge or trial.[45][46]

Police brutality

The deployment of plainclothes forces paid by Mubarak's ruling party, Baltageya[47] (Template:Lang-ar), has been a hallmark of the Mubarak government.[47] The Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights has documented 567 cases of torture, including 167 deaths, by police that occurred between 1993 and 2007.[48] On 6 June 2010, Khaled Mohamed Saeed died under disputed circumstances in the Sidi Gaber area of Alexandria. Multiple witnesses testified that Saeed was beaten to death by the police.[49][50] Activists rallying around a Facebook page called "We are all Khaled Said" succeeded in bringing nationwide attention to the case.[51] Mohamed ElBaradei, former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, led a rally in 2010 in Alexandria against alleged abuses by the police and visited Saeed's family to offer condolences.[52]

Economic challenges

- Demographic

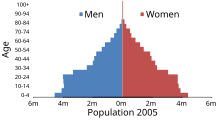

The population of Egypt grew from 30,083,419 in 1966[53] to roughly 79,000,000 by 2008.[54] The vast majority of Egyptians live in the limited spaces near the banks of the Nile River, in an area of about 40,000 square kilometers (15,000 sq mi), where the only arable land is found and competing with the need of human habitations. In late 2010, around 40 percent of Egypt's population of just under 80 million lived on the fiscal income equivalent of roughly US$2 per day with a large part of the population relying on subsidised goods.[11]

According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the basic problem Egypt has is unemployment driven by a demographic youth bulge: with the number of new people entering the job force at about 4 percent a year, unemployment in Egypt is almost 10 times as high for college graduates as it is for people who have gone through elementary school, particularly educated urban youth, who are precisely the people currently seen out in the streets.[55]

- Reform, growth, and poverty

Egypt's economy was highly centralized during the rule of former President Gamal Abdel Nasser but opened up considerably under former President Anwar Sadat and Mubarak. The Mubarak-led government from 2004 to 2008 aggressively pursued economic reforms to attract foreign investment and facilitate GDP growth, but postponed further economic reforms because of global economic turmoil. The international economic downturn slowed Egypt's GDP growth to 4.5 percent in 2009. In 2010, analysts assessed the government of Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif would need to restart economic reforms to attract foreign investment, boost growth, and improve economic conditions for the broader population. Despite high levels of national economic growth over the past few years, living conditions for the average Egyptian remained poor.[56]

Corruption

Political corruption in Mubarak administration's Ministry of Interior has risen dramatically due to the increased power over the institutional system necessary to prolong the presidency.[57] The rise to power of powerful business men in the NDP in the government and the People's Assembly led to massive waves of anger during the years of Prime Ministers Ahmed Nazif's government. An example of that is Ahmed Ezz's monopolizing the steel industry in Egypt by holding more than 60 percent of the market share.[58] Aladdin Elaasar, an Egyptian biographer and an American professor, estimates that the Mubarak family is worth from $50 to $70 billion.[59][60]

The wealth of Ahmed Ezz, the former NDP Organisation Secretary, is estimated to be 18 billion Egyptian pounds;[61] The wealth of former Housing Minister Ahmed al-Maghraby is estimated to be more than 11 billion Egyptian pounds;[61] The wealth of former Minister of Tourism Zuhair Garrana is estimated to be 13 billion Egyptian pounds;[61] The wealth of former Minister of Trade and Industry, Rashid Mohamed Rashid, is estimated to be 12 billion Egyptian pounds;[61] and the wealth of former Interior Minister Habib al-Adly is estimated to be 8 billion Egyptian pounds.[61]

The perceptions of corruption and its beneficiaries being limited to businessmen with ties to the National Democratic Party have created a picture "where wealth fuels political power and political power buys wealth."[62]

During the Egyptian parliamentary election, 2010, opposition groups complained of harassment and fraud perpetrated by the government. As such opposition and civil society activists have called for changes to a number of legal and constitutional provisions which affect elections.

In 2010, Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index report assessed Egypt with a CPI score of 3.1, based on perceptions of the degree of corruption from business people and country analysts (with 10 being clean and 0 being totally corrupt).[63]

Foreign relations

Foreign governments in the West including the US have regarded Mubarak as an important ally and supporter in the Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations.[35] After wars with Israel in 1967 and '73, Egypt signed a peace treaty in 1979, provoking controversy in the Arab world. As provisioned in the 1978 Camp David Accords, which led to the peace treaty, both Israel and Egypt receive billions of dollars in aid annually from the United States, with Egypt receiving over US$1.3 billion of military aid each year in addition to economic and development assistance.[64] Many Egyptian youth feel ignored by Mubarak on the grounds that he is not looking out for their best interests and that he rather serves the interests of the West.[clarification needed][65] The cooperation of the Egyptian regime in enforcing the blockade of the Gaza Strip was also deeply unpopular amongst the general Egyptian public.[66]

Military

The Egyptian Armed Forces enjoy a better reputation with the public than the police do, the former perceived as a professional body protecting the country, the latter accused of systemic corruption and illegitimate violence. All four Egyptian presidents since the 1950s have come from the military into power. Key Egyptian military personnel include the defense minister Mohamed Hussein Tantawi and General Sami Hafez Enan, chief of staff of the armed forces.[67][68] The Egyptian military totals around 468,500 well-armed active personnel, plus a reserve of 479,000.[69]

Lead-up to the protests

In background preparation for a possible overthrow of Mubarak, opposition groups had studied the work of Gene Sharp on non-violent revolution, including working with leaders of Otpor!, the student-led Serbian uprising in 2000. Copies of Sharp's list of 198 non-violent "weapons", translated into Arabic and not always attributed to him, were circulating in Tahrir Square during its occupation.[70][71]

Tunisian uprising

After the ousting of Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali due to mass protests, many analysts, including former European Commission President Romano Prodi, saw Egypt as the next country where such a revolution might occur.[72] The Washington Post comments on this saying "The "Jasmine Revolution," [...] should serve as a stark warning to Arab leaders - beginning with Egypt's 83-year-old Hosni Mubarak - that their refusal to allow more economic and political opportunity is dangerous and untenable."[73] However, others argued on the contrary citing little aspiration of the Egyptian people, low educational levels and a strong government with the support of the military.[74] The BBC said "The simple fact is that most Egyptians do not see any way that they can change their country or their lives through political action, be it voting, activism, or going out on the streets to demonstrate." [75]

Self-immolation

On 17 January due to rising discontent with the country's state and the poor living conditions, and following the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia, a man set himself ablaze in front of the Egyptian parliament;[76] about five more attempts of self-immolation followed suit.[74]

Online activism

We Are All Khaled Saeed is a Facebook group which formed in the aftermath of Saeed's beating and death. The group attracted hundreds of thousands of members worldwide and played a prominent role in spreading and bringing attention to the growing discontent. As the protests began, Google executive Wael Ghonim revealed that he was the person behind the account.[77] Another potent viral online contribution was made by Asmaa Mahfouz, a female activist who posted a video in which she challenged people to publicly protest.[78]

National Police Day protests

Opposition groups were planning a day of revolt for 25 January coinciding with the National Police Day. The goal for the protests was to protest against abuses by the police in front of the ministry of interior.[79] These demands expanded to be the resignation of the minister of Interior, the restoration of a fair minimum wage, the end of Emergency Law and the limitation of the presidency to two terms. A major supporter for the protests was the April 6 Youth Movement, which distributed 20,000 leaflets saying "I will protest on 25 January to get my rights".

Security forces however deemed the protests as "illegal", not having the required permissions to proceed and would therefore deal with it strictly.[80] Many political movements, opposition parties and public figures chose to support the day of revolt including Youth for Justice and Freedom, the Popular Democratic Movement for Change and the National Association for Change, however, its leader Mohamed El Baradei did not support doing protests saying that he "would like to use the means available from within the system to effect change".[81] The Ghad, Karama, Wafd and Democratic Front parties also lend their support to the protests. Public figures including novelist Alaa Al Aswany, writer Belal Fadl and actors Amr Waked and Khaled Aboul Naga announced they would also participate, while the facebook group set for the event attracted 80,000 attendees. However, the Tagammu Party and the Muslim brotherhood stated they would not participate. The Coptic church also urged Christians not to participate in the protests.[82]

In a final attempt to calm the situation down, on 24 January the government announced they found the mastermind behind the Alexandria church bombing, accusing the "Army of Islam" of planning the incident.[83]

Protests

Timeline

25 January 2011: The "Day of Revolt", nationwide protests against the government of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak began. Tens of thousands of protestors gathered in Cairo, with thousands more in cities throughout Egypt. The protests were generally non-violent, but there were reports of some casualties among both civilians and police.

28 January 2011: The “Friday of Rage” protests began. Shortly after Friday prayers, hundreds of thousands gathered in Cairo and other Egyptian cities. Opposition leader Mohammed ElBaradei traveled to Cairo to participate. Some looting was reported. Police forces withdrew from the streets completely. and the Egyptian government ordered the military to assist police. International fears of violence grew, but no major casualties were reported.

29 January 2011: Protests continued as military presence in Cairo increased. A curfew was instituted, but protests continued throughout the night. The military showed restraint, reportedly refusing to obey orders to use live ammunition; there were no reports of major casualties.

1 February 2011: After continued nationwide unrest, Mubarak addressed the people and offered several concessions. In addition to proclaiming he would not run for another term in the September 2011 elections, he promised political reforms. He said that he would stay in office to ensure a peaceful transition. Pro-Mubarak and anti-Mubarak groups began to clash in small but violent interactions throughout the night.

2 February 2011: Violence escalated as waves of Mubarak supporters met anti-government protestors. The military limited the violence, constantly separating anti-Mubarak and pro-Mubarak groups. President Mubarak, in interviews with various news agencies, refused to step down. Violence toward international journalists and news agencies escalated; speculation grew that Mubarak was actively increasing instability as a way to step in and end the protests.

5 February 2011: Protests in Cairo and throughout the nation continued. Egyptian Christians held Sunday Mass in Tahrir Square, protected by a ring of Muslims. Negotiations began between Egyptian Vice President Omar Suleiman and opposition representatives. The Egyptian army increased its security role, maintaining order and protecting Egypt’s museums. Suleiman offered political and constitutional reforms while other members of the Mubarak regime accuses nations, including the US, of interfering in Egypt’s affairs.

10 February 2011: Mubarak formally addressed Egypt amid reports of a possible military coup, but instead of his expected resignation, he stated his powers would transfer to Vice President Suleiman, and he would remain in Egypt as its head of state. Anger and disappointment spread through crowds in Cairo, and demonstrations began to escalate in number and intensity throughout Egypt.

11 February 2011: The "Friday of Departure", massive protests in response to Mubarak’s speech continued in many Egyptian cities. At 6:00 p.m. local time, Suleiman announced Mubarak's resignation and that the Supreme Council of Egyptian Armed Forces would assume leadership of the country.

13 February 2011: The Supreme Council of Egyptian Armed Forces dissolved Egypt’s parliament and suspended the Constitution. The council also declared that it would hold power for six months or until elections could be held, whichever came first. ElBaradei urged the council to provide more details to the Egyptian people regarding its plans. Major protests subsided but uncertainty remained, and many pledged to keep returning to Tahrir square until all demands had been met.

Cities and regions

- Cairo

Cairo has been at the epicentre of much of the crisis. The largest protests were held in downtown Tahrir Square, which was considered the "protest movement’s beating heart and most effective symbol."[84] On the first three days of the protests, there were clashes between the central security police and protesters and as of 28 January, police forces withdrew from most of Cairo. Citizens then formed neighbourhood watch groups to keep the order as widespread looting was reported. Traffic police were reintroduced to Cairo on the morning of 31 January.[85] Estimated 2 million people protested at Tahrir square.[86]

- Alexandria

Alexandria, the home of Khaled Saeed, had major protests and clashes against the police. Demonstrations continued and one on 3 February was reported to include 750,000 people.[citation needed]There were few confrontations as not many Mubarak supporters were around, except in occasional motorized convoys escorted by police. The breakdown of law and order, including the general absence of police on the streets, continued through to at least the evening of 3 February, including the looting and burning of one the country's largest shopping centres.[citation needed] Alexandria protests were notable for the presence of Christians and Muslims jointly taking part in the events following the church bombing on 1 January.

- Mansoura

In the northern city of Mansoura there were protests against the Mubarak regime every day from 25 January onwards. One protest on 1 February was estimated at one million people,[citation needed] while on 3 February, 70,000 people were reported on the streets.[citation needed]

- Siwa

The remote city of Siwa has thus far been reported as relatively calm.[87] Local sheikhs, who were reportedly in control of the community, put the community under lockdown after a nearby town was "torched."[88]

- Suez

The city of Suez has seen the most violence of the protests thus far. Eyewitness reports have suggested that the death toll there may be higher, although confirmation has been difficult due to a ban on media coverage in the area.[89] Some online activists have referred to Suez as Egypt's Sidi Bouzid, the Tunisian city where protests started.[90] A labour strike was held on 8 February.[91] Large protests took place on 11 February.[92]

Tanta

Tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets from the the first day (Jan. 25th) and most of the days after till feb. 11st . It exceeded a hundred thousand many times. Some hospitals reported casualties during the clashes of friday Jan. 28th .

Beni Suef

City of Beni Suef have seen repeated protests in front of the City Hall On el Kourneish, in front of Omar abd el Aziz Mosque, and in El Zerayeen Square, on most days of the protests and demonstrations. 12 protesters have been killed when Police Opened fire at Mass groups protesting in front of the Police Station in Beba, South Beni suef. Many Others got injured. Thugs and Outlaws have robbed many Governmental Garages and burned down several Governmental buildings.

- Luxor

There were also protests in Luxor.[93]

- Sinai Peninsula

Bedouins in the Sinai Peninsula fought the security forces for several weeks.[94]

- Sharm-El-Sheikh

No protests or civil unrest took place in Sharm-El-Sheikh on 31 January.[95] All was still calm as Hosni Mubarak and his family left on 11 February.[92]

- Deirout

Police opened fire on protesters in the Deirout near the southern suburbs of Cairo and Asyut, on 11 February.[92]

- Shebin el-Kom

Tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Shebin el-Kom on 11 February.[92]

- El-Arish

Thousands protested in the city of El-Arish, in the Sinai Peninsula on 11 February.[92]

- Sohag

Large protests took place in the southern city of Sohag on 11 February.[92]

- Minya

Large protests took place in the southern city of Minya on 11 February.[92]

- Ismailia

Nearly 100,000 people protested in and about the local government headquarters in Ismailia on 11 February.[92]

- Kafr El Sheikh

a large protests took place on 28 January and 4 February all over Kafr el-Sheikh.[citation needed]

Deaths

Leading up to the protests, at least six cases of self-immolation were reported, including a man arrested while trying to set himself on fire in downtown Cairo.[96] These cases were inspired by, and began exactly one month after, the acts of self-immolation in Tunisia triggering the 2010–2011 Tunisian uprising. Six instances have been reported, including acts by Abdou Abdel-Moneim Jaafar,[97] Mohammed Farouk Hassan,[98] Mohammed Ashour Sorour,[99] and Ahmed Hashim al-Sayyed who later died from his injuries.[100]

As of 30 January, Al Jazeera reported as many as 150 deaths in the protests.[101] The Sun reported that the dead could include at least 10 policemen, 3 of whom were killed in Rafah by "an enraged mob".[102]

By 29 January, 2,000 people were known to be injured.[103] The same day, an employee of the Azerbaijani embassy in Egypt was killed while returning home from work in Cairo;[104] the next day Azerbaijan sent a plane to evacuate citizens[105] and opened a criminal investigation into the death.[106]

Funerals for the dead on the "Friday of Anger" were held on 30 January. Hundreds of mourners gathered for the funerals calling for Mubarak's removal.[107] By 1 February, the protests had left at least 125 people dead,[108] although Human Rights Watch said that UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay claimed that as many as 300 people may have died in the unrest. This unconfirmed tally included 80 Human Rights Watch-verified deaths at two Cairo hospitals, 36 in Alexandria, and 13 in the port city of Suez, amongst others;[109][110][111] over 3,000 people were also reported as injured.[109][110][111] Template:2011 Egyptian protests Death Toll

Domestic responses

On 29 January, Mubarak indicated he would be changing the government because despite a "point of no return" being crossed, national stability and law and order must prevail, that he had requested the government, formed only months ago, to step down, and that a new government would be formed.[112][full citation needed][113] He then appointed Omar Suleiman, head of Egyptian Intelligence, as vice president and Ahmed Shafik as prime minister.[114] On 1 February, he spoke again saying he would stay in office until the next election in September 2011 and then leave without standing as a candidate. He also promised to make political reforms.

Various opposition groups,[clarification needed] including the Muslim Brotherhood, reiterated demands for Mubarak's resignation. The MB also said, after protests turned violent, that it was time for the military to intervene.[115] Mohammed ElBaradei, who said he was ready to lead a transitional government,[116] was also the consensus candidate by a unified opposition including: the April 6 Youth Movement, We Are All Khaled Said Movement, National Association for Change, 25 January Movement, Kefaya and the Muslim Brotherhood.[117] ElBaradei formed a "steering committee".[118] On 5 February, a "national dialogue" was started between the government and opposition groups to work out a transitional period before democratic elections.

Many of Al-Azhar Imams joined the protesters on 30 January all over the country.[119] Christian leaders asked their congregations to stay away from protests, though a number of young Christian activists joined the protests led by Wafd Party member Raymond Lakah.[120]

The Egyptian state also cracked down on the media, shutting down internet access[121] on the first day of the protests for over a week. Journalists were also harassed by the regime's supporters, eliciting condemnation from the Committee to Protect Journalists, European countries and the United States.

Egyptian and foreign equity and commodity markets also reacted negatively to the increasing instability.

On 13 February, an article in the state-controlled newspaper, Al-Ahram, questioned the inclinations of Google Inc. and its executive and activist, Wael Ghoneim, due to certain translation errors when using the Google Translate engine that were perceived as dubious by some.[122] One reported error was translating any fictitious phrase along the lines of "... occupies Israel" in Arabic into "Israel occupies..." in English. Google Translate is a statistical translation engine that uses web search statistics rather than grammatical rules to yield a probable translation.[123] Since "...occupies Israel" is a low-probability query owing to the fact that Israel has not been occupied and "Israel occupies..." is a higher-probability query on the other hand, the limitation of statistical translation results in the inaccurate translation.

International reactions

International reactions have varied with most Western states saying peaceful protests should continue but also expressing concern for the stability of the country and the region. Many states in the region expressed concern and supported Mubarak, while others like Tunisia and Iran supported the protests. Israel was most cautious for change, with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asking his government ministers to maintain silence and urging Israel's US and European allies to curb their criticism of President Mubarak;[124][125] however, an Arab-Israeli parliamentarian supported the protests. There were also numerous solidarity protests for the anti-government protesters around the world.

NGOs also expressed concern about the protests and the ensuing heavy-handed state response. Many countries also issued travel warnings or began evacuating their citizens. Even multinational corporations began evacuating their expatriate workers.[126]

Post-ousting

Amid the growing concerns for the country, on 21 February, David Cameron, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, became the first world leader to visit Egypt since Mubarak was ousted as the president 10 days previously. A news blackout was lifted as the prime minister landed in Cairo for a brief five-hour stopover hastily added at the start of a planned tour of the Middle East.[127]

Regional instability

Greater Middle East

Template:2010–2011 MENA protests HTK

Major uprisings, demonstrations and protests have spread to the Middle East and North Africa from Tunisia. To date Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Libya, Morocco and Yemen have all seen major protests, and minor incidents have occurred in Iraq, Kuwait, Mauritania, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan and Syria.

Iran

The 32nd anniversary of the Iranian Revolution was said to have had a low turnout on 11 February 2011. (The state-run Kayhan newspaper claimed a 50 million turnout, despite Iran having a population of only 75 million.) At the behest of Mir-Hossein Moussavi and Mehdi Karroubi, opposition leaders called for nationwide protest marches for 14 February. Rumours suggested that the protesters would include university students, lorry drivers and gold merchants from across the country under the umbrella opposition known as the Green movement in what was seen as an inspiration of events from Egypt and Tunisia. The Revolutionary Guard said it would forcefully confront protesters.[128] Opposition activists and aides to Mousavi and Karroubi had been arrested in the days before the protests.

The opposition protesters used a similar tactic from the 2009 protests in which they chanted "Allahu Akbar" and "Death to the dictator" into the early morning hours. However, rather than using slogans praising Mousavi like in 2009, protestors have been widely chanting "Mubarak, Ben Ali, Now its time for Seyed Ali [Khamenei]". Reports from the demonstrations of 14 February describe clashes between protesters and security forces in Tehran, where 10,000 security forces had been deployed to prevent protesters from gathering at Azadi Square, where the marches, originating from Enghelab, Azadi and Vali-Asr streets, were expected to converge. Police reportedly fired tear gas and used pepper spray and batons to disperse protesters. Clashes were also reported in Isfahan.[129] It was reported up to a third of a million protesters marched in Tehran alone on 14 February.[130]

Reform process

The protests initiated a process of social and political reform by articulating a series of demands. Reform began with President Mubarak's announcements that concessions would be made towards reform and was highlighted by his resignation 18 days after the protests started. The list of demands for broader changes in Egyptian society and governance, articulated by protesters and activists, includes the following:

| Demand | Status | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Resignation of president Mohammed Hosni Mubarak | met | 11 February |

| 2. Canceling the Emergency Law | announced[citation needed] | within 6 months |

| 3. Dismantling the secret police | under discussions[citation needed] | |

| 4. Announcement by (Vice-President) Omar Suleiman that he will not run in the next presidential elections | met[132] | 3 February |

| 5. Dissolving the Parliament and Shura Council | met | 13 February |

| 6. Releasing all prisoners taken since 25 January | announced[citation needed] | 20 February |

| 7. Ending the curfew | relaxed | 11 February |

| 8. Dismantling the university guards system | ||

| 9. Investigation of officials responsible for violences against protesters and for the organised thuggery | ||

| 10. Firing minister of information Anas el-Fiqqi and stopping propaganda from government owned media | met | 12 February |

| 11. Reimbursing shop owners for their losses during the curfew | ||

| 12. Announcing the demands above on government television and radio | met[citation needed] | 11-18 February |

On 17 February, an Egyptian prosecutor ordered the detention of three ex-ministers, former Interior Minister Habib el-Adli, former Tourism Minister Zuhair Garana and former Housing Minister Ahmed el-Maghrabi, and a prominent businessman, steel magnate Ahmed Ezz, pending trial on suspicion of wasting public funds. The public prosecutor also froze the accounts of Adli and his family members on accusations that over 4 million Egyptian pounds ($680,000) were transferred to his personal account by a head of a contractor company, while calling on the foreign minister to contact European countries and ask them to freeze the accounts of the defendants.[133]

Meanwhile, the United States announced on the same day that it was giving Egypt $150 million in crucial economic assistance to help the key US ally transition towards democracy following the overthrow of long time president Mubarak. US secretary of state Hillary Clinton said that William Burns, the undersecretary of state for political affairs, and David Lipton, a senior White House adviser on international economics, would travel to Egypt the following week.[133]

On 19 February, a moderate Islamic party, named (Template:Lang-ar) Al-Wasat Al-Jadid, or the New Center Party, which was outlawed for 15 years was granted official recognition Saturday by an Egyptian court. The party was founded in 1996 by activists who split off from the Muslim Brotherhood and sought to create a tolerant Islamic movement with liberal tendencies, but its attempts to register as an official party were rejected four times since then. On the same day, Prime Minister Ahmed Shafiq said 222 political prisoners would be released. He said only a few were detained during the popular uprising and put the number of remaining political prisoners at 487, but did not say when they would be released.[134]

On 20 February, Dr. [[{{{1}}}]] an well known activist and law professor, announced (on TV channels) accepting a vice prime minister position at a new government that will be announced on 21-22 February. He announced removing many of the previous government members to palliate the situation.

See also

- 2010–2011 Arab world protests

- Egyptian Revolution of 1919

- Democracy in the Middle East

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

- 2007–2008 world food price crisis

- Demographic trap

- Youth bulge

- People Power Revolution

- Iranian Revolution

References

- ^ "Revolution might not be a cure for Egypt's extreme poverty". 'Los Angeles Times World. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt's revolution death toll rises to 384". Al Masry Al Youm. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt: Documented Death Toll From Protests Tops 300 | Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Unrest in Egypt". Reuters. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ "Egypt: Mubarak Sacks Cabinet and Defends Security Role". BBC News. 29 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ "Protests in Egypt — As It Happened (Live Blog)". The Guardian. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ News Service, Indo-Asian (30 January 2011). "10 killed as protesters storm Cairo building". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Davies, Wyre. "Egypt Unrest: Protesters Hold Huge Cairo Demonstration". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Around 365 dead in Egypt protests: health ministry". 17 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Osman, Ahmed Zaki (26 January 2011). "At Least 1,000 Arrested During Ongoing 'Anger' Demonstrations". Almasry Alyoum. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e AFP (25 January 2011). "Egypt braces for nationwide protests". France24. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (25 January 2011). "Violent Clashes Mark Protests Against Mubarak's Rule". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Net down, special forces deployed in Cairo as Egypt braces for protests". News Limited. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Fall of Mubarak Shakes Middle East". Wall Street Journal. 12 February 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Mubarak Resigns Under Intense Pressure from Protesters". Infoplease. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ "Q&A: What's Behind the Unrest?". SBS. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Egypt activists plan biggest protest yet on Friday". Al Arabiya. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ a b c AFP (27 January 2011). "Egypt protests a ticking time bomb: Analysts". The New Age. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ "Egyptian Activists' Action Plan: Translated". The Atlantic. 27 January 2011.

- ^ "Trade unions: the revolutionary social network at play in Egypt and Tunisia". Defenddemocracy.org. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ "Protests in Egypt and unrest in Middle East – as it happened". The Guardian. UK. 25 January 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Fleishman, Jeffrey and Edmund Sanders (Los Angeles Times) (29 January 2011). "Unease in Egypt as police replaced by army, neighbors band against looters". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Looting spreads in Egyptian cities". Al Jazeera English. 29 January 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Hauslohner, Abigail (29 January 2011). "The Army's OK with the Protesters, for now". Time.com. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Mubarak plays last card, the army; Police vanish". World Tribune (online). 31 January 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Stirewalt, Chris (31 January 2011). "Egypt: From Police State to Military Rule". Fox News. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Regional Reaction Mixed For Egypt Protests". Eurasia Review. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ "Travel warning issued, evacuation to start as protests continue in Egypt". English People's Daily Online. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Shadid, Anthony; Kirkpatrick, David D. (30 January 2011). "Opposition Rallies to ElBaradei as Military Reinforces in Cairo". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ El Deeb, Sarah; Al-Shalchi, Hadeel (1 February 2011). "Egypt Crowds Unmoved by Mubarak's Vow Not To Run". Associated Press (via ABC News). Retrieved 1 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Hosni Mubarak resigns as president". Al-Jazeera English. 11 February 2011.

- ^ el-Malawani, Hania (13 February 2011). "Egypt's military dismantles Mubarak regime".

- ^ "The 25 January Revolution (Special issue)". Al-Ahram Weekly. 10–16 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt: A Nation in Waiting". Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Hosni Mubarak". The New York Times. 8 March 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "History's crossroads". Indianexpress.com. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Law 1958/162 (Emergency Law)". Template:Ar at EMERglobal Lex January 2011, part of the Edinburgh Middle East Report. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ a b Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights (28 May 2008). "Egypt and The Impact of 27 years of Emergency on Human Rights". Archived from the original on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Shehata, Samer (26 March 2004). "Egypt After 9/11: Perceptions of the United States". Contemporary Conflicts. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Caraley, Demetrios (2004). American Hegemony: Preventive War, Iraq, and Imposing Democracy. Academy of Political Science. ISBN 1-8848-5304-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Choney, Suzanne (27 January 2011). "Egyptian bloggers brave police intimidation". MSNBC. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Mayer, Jane (30 October 2006). "The C.I.A.'s Travel Agent". The New Yorker. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Fakta, Kalla (18 May 2004). "Striptease brevpapperl Agent". trojkan.se. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Shenker, Jack (22 November 2010). "Egyptian Elections: Independents Fight for Hearts and Minds in 'Fixed Ballot'". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Press release (29 June 2010). "Egypt: Keep Promise to Free Detainees by End of June: Joint Statement". Amnesty International. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Holder, R. Clemente (July/August 1994). "Egyptian Lawyer's Death Triggers Cairo Protests". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b (registration required) Kirkpatrick, David; Fahim, Kareem (3 February 2011). "Gunfire Rings Out as Protesters Clash". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Staff writer (13 August 2007). "Egyptian Police Sued for Boy's Death". BBC News. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Khalil, Ashraf (25 June 2010). "Anger in Alexandria: 'We're Afraid of Our Own Government'". Almasry Alyoum. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Two Witnesses Affirm Alexandria Victim Beaten by Police". Almasry Alyoum. 19 June 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Levinson, Charles (2 February 2011). "How Cairo, U.S. Were Blindsided by Revolution". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "ElBaradei Leads Anti-Torture Rally". Al Jazeera English. 26 June 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ^ The British Oxford economic atlas of the World 4th edition, ISBN 0198941072

- ^ "Central Agency for Population Mobilisation and Statistics — Population Clock (July 2008)". Msrintranet.capmas.gov.eg. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "The long-term economic challenges Egypt must overcome". Marketplace. 1 February 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt Economy 2010". 27 January 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help) - ^ Rutherford, Bruce (2008). Egypt after Mubarak: Liberalism, Islam, and Democracy in the Arab World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-6911-3665-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The Report: Egypt 2007. Oxford Business Group. 2007. ISBN 1-9023-3957-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Elaasar, Aladdin (28 January 2011). "Egyptians Rise Against Their Pharoah". Huffington Post. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt's Mubarak Likely to Retain Vast Wealth". ABC News. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e "Obama optimistic about Egypt as negotiators make concessions". AHN. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Inside Story. "How did Egypt become so corrupt? - Inside Story". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ "CPI 2010 table". Transparency International. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ "Background Note: Egypt". United States Department of State. 10 November 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Cole, Juan (essay) (30 January 2011). "Why Egypt's Class Conflict Is Boiling Over – Juan Cole: How Decades of Economic Stumbles Set the Stage for Egypt's Current Political Turmoil". CBS News. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Mubarak under pressure | World news | guardian.co.uk". Guardian. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Key members of Egypt Armed Forces Supreme Council". Apnews.myway.com. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Black, Ian (30 January 2011). "All Eyes on Egypt's Military as Hosni Mubarak Fortifies Position". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (30 January 2011). "Factbox – Egypt's Powerful Military". Reuters. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ KIRKPATRICK, DAVID and SANGER, DAVID (13 February 2011). "New York Times". New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Gene Sharp: Author of the nonviolent revolution rulebook". BBC News. 21 February 2011.

- ^ Remondini, Chiara (16 January 2011). "Prodi Says Egypt to Be Monitored After Tunisia, Messaggero Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Tunisia's revolution should be a wake-up call to Mideast autocrats". Washington Post. 15 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ a b Hauslohner, Abigail (20 January 2011). "After Tunisia: Why Egypt Isn't Ready to Have Its Own Revolution". Time. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Leyne, Jon (17 January 2011). "No sign Egypt will take the Tunisian road". BBC. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ Zayed, Dina (16 January 2011). "Egyptians set themselves ablaze after Tunisia unrest". Reuters. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Who is Wael Ghonim?". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ "Women play vital role in Egypt's uprising" (transcript). National Public Radio. February 4, 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ "Muslim Brotherhood to participate in 25 January protest". Al Masry Al Youm. 23 January 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Security forces to deal strictly with 'illegal' 25 January protest". Al Masry Al Youm. 23 January 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Shenker, Jack (18 January 2011). "Mohamed ElBaradei warns of 'Tunisia-style explosion' in Egypt". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Afify, Heba (24 January 2011). "Activists hope 25 January protest will be start of 'something big'". Al Masry Al Youm. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ El-Hennawy, Noha (24 January 2011). "Monday's papers: Alex bombing perpetrator announced, and Day of Loyalty vs Day of Revolt". Al Masry Al Youm. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Al Jazeera online producer. "The different shades of Tahrir - Anger in Egypt". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt Unrest and Protests Continue as Police Return to Cairo Streets". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "Estimated 2 Million People Protest In _ Around Tahrir Square In Cairo Egypt.mp4 | Current News World Web Source for News and Information". Cnewsworld.com. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ^ Sterling, Joe (February 4, 2011). "Across dusty Egypt, anxiety has filled the air". CNN. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Mistry, Manisha (31 January 2011). "Mother from St. Albans Speaks to the Review from Egypt". St. Albans Review (part of Newsquest). Retrieved 4 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Tencer, Daniel (14 January 2011). "Reports of 'Massacre' in [[Suez]] as [[Protests]] in [[Egypt]] Move into Third day". The Raw Story. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Dziadosz, Alexander (27 January 2011). "Could Suez be Egypt's Sidi Bouzid?". Reuters. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ "As Egypt Protest Swells, U.S. Sends Specific Demands". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schemm, Paul; Michael, Maggie (5 February 2011). "Mubarak leaves Cairo for Sinai as protests spread". SignOnSanDiego.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt Travel Advice". Fco.gov.uk. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Protests Swell in Rejection of Egypt's Limited Reforms". New York Times. February 8, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ Stevenson, Rachel. "Sharm El-Sheikh's Tourists Talking About a Revolution". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Rosenberg, David (24 January 2011). "Self-Immolation Spreads Across the Mideast, Inspiring Protest, Controversy". The Media Line. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "مصري يحرق نفسه أمام البرلمان". Al Jazeera (in Arabic). 17 January 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Zayed, Dina (18 January 2011). "Egyptians Set Themselves Ablaze After Tunisia Unrest". Reuters. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "موظف بـ'مصر للطيران' يهدد بحرق نفسه أمام نقابة الصحفيين". El-Aosboa (newspaper) (in Arabic). 18 January 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Staff writer (18 January 2011). "Mother of Ahmed Hashim al-Sayyed". Reuters (via Yahoo! News). Retrieved 2 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Tomasevic, Goran (30 January 2011). "Curfew Hours Extended in Egypt as Turmoil Continues". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ Parker, Nick (29 January 2011). "Troops Battle Rioters in Egypt". The Sun. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Update 1-Death Toll in Egypt's Protests Tops 100 – Sources". Reuters. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Agayev, Zulfugar (30 January 2011). "Azerbaijani Embassy Worker Shot Dead in Egypt, Ministry Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ "Ambassador: Embassy will continue providing necessary help to Azerbaijanis in Egypt". En.trend.az. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ "Prosecutor General's Office Files Lawsuit on Murder of Accountant of Azerbaijani Embassy in Egypt". 31 January 2011.

- ^ Nolan, Dan (29 January 2011). "Hundreds Mourn the Dead in Egypt". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (31 January 2011). "Egypt Crisis: Country Braced for 'March of a Million'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ a b 1 February 2011 . "Egypt: Rights Advocates Report Protest Death Toll as High as 300". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Text " 9:48 am" ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Egypt Unrest Claimed About 300 Lives – UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay". Allvoices.com. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ a b Staff writer (1 February 2011). "UN Human Rights Chief: 300 Reported Dead in Egypt Protests". Haaretz. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Breaking News. Al Jazeera English. 29 November 1:30 Egypt time

- ^ Staff writer (29 January 2011). "Protesters Return to Cairo's Main Square – Egyptian President Fires His Cabinet But Refuses To Step Down". MSNBC. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Slackman, Michael (29 January 2011). "Choice of Suleiman Likely to Please the Military, Not the Crowds". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ "Live: Egypt Unrest". BBC News. 28 January 2011. Archived from the original on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

Mubarak must step down. It is time for the military to intervene and save the country

- ^ Memmott, Mark (27 January 2011). "ElBaradei Back In Egypt; Says It's Time For A New Government: The Two-Way". NPR. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ "الجيش يدفع بتعزيزات اضافية وطائرات حربية تحلق فوق المتظاهرين في القاهرة". BBC Arabic (in Arabic). 30 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "لجنة وطنية لمفاوضة نظام مبارك". Al Jazeera (in Arabic). 30 January 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trasn_title=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "خالد الصاوي يقود مظاهرة في ميدان التحرير". Elaph (in Arabic). 30 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "الكنيسة بمنأى عن مظاهرات مصر". Al Jazeera (in Arabic). 27 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Cowie, James (27 January 2011). "Egypt Leaves the Internet". Renesys. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Sara Ne'mat-Allah (13 February, 2011). "Al-Ahram: Google translation sparks disappointment at Wael Ghoneim".

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Text "publisher-Al-Ahram" ignored (help) - ^ Lee Gomes (July 22, 2010). "Forbes: Google Translate tangles with computer learning".

{{cite news}}: Text "publisher-Forbes" ignored (help) - ^ "Israel's Big Fears over a Post-Mubarak Egypt". Euronews. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ "Israel Urges World To Curb Criticism of Egypt's Mubarak". Haaretz. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ "Foreign governments, businesses begin evacuations from Egypt". CNN. 30 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "David Cameron visits Egypt - The Guardian". www.guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ D. Parvaz. "Iran opposition 'planning protests' - Middle East". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Al Jazeera English. "Clashes reported in Iran protests". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ "Iran Live Blog: 25 Bahman / 14 February - Tehran Bureau | FRONTLINE". PBS. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt: A List of Demands from Tahrir Square". Global Voices. 10 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt's Suleiman says will not run for president". Reuters Africa. 3 February 2011.

- ^ a b Al-Jazeera English (17 February 2011). "Egypt detains ex-ministers". Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ "Egypt recognizes moderate Islamic party, promises to release political prisoners". 19 February 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

External links

- General

- Egypt Resources from Google Crisis Response

- Template:BOTW

- Live coverage

- "Live blog - Egypt". Al Jazeera English. Qatar.

- "Egypt's new era". BBC News. UK.

- "Egypt protests live". The Guardian. UK.

- "Unrest in Egypt". Reuters. UK.

- Egypt Real Time Video Stream at Frequency

- Emergency Law and Police Brutality in Egypt at CrowdVoice

- Citizen Media coverage on Egypt Protests by Global Voices Online

- Testimonials From Egyptians at The Real News

- Interviews

- Interview with Wael Ghonim, Google mideast manager (Youtube, Arabic); with subtitles

- Documentaries