Winfield Scott: Difference between revisions

→Cherokee Removal: *sigh* |

|||

| Line 119: | Line 119: | ||

Arriving at [[New Echota]], Cherokee Nation, on April 6, 1838, Scott immediately divided the Cherokee Nation into three military districts. He designated May 26, 1838 as the beginning date for the first phase of the removal. The first phase involved the Cherokees in Georgia. He preferred Army regular troops to Georgia militiamen for the operation because the militiamen stood to benefit from the removal; some militiamen, for example, already laid claim to Cherokee properties.<ref>Eisenhower, 188-91.</ref> Because the promised regulars did not arrive in time, however, Scott proceeded with four thousand Georgia militia. |

Arriving at [[New Echota]], Cherokee Nation, on April 6, 1838, Scott immediately divided the Cherokee Nation into three military districts. He designated May 26, 1838 as the beginning date for the first phase of the removal. The first phase involved the Cherokees in Georgia. He preferred Army regular troops to Georgia militiamen for the operation because the militiamen stood to benefit from the removal; some militiamen, for example, already laid claim to Cherokee properties.<ref>Eisenhower, 188-91.</ref> Because the promised regulars did not arrive in time, however, Scott proceeded with four thousand Georgia militia. |

||

The moral implications of the policies of Presidents Jackson and Van Buren did not make Scott's orders easy. He reassured the Cherokee people of proper treatment. In his instructions to the militiamen under his command, Scott called any acts of harshness and cruelty " |

The moral implications of the policies of Presidents Jackson and Van Buren did not make Scott's orders easy. He reassured the Cherokee people of proper treatment. In his instructions to the militiamen under his command, Scott called any acts of harshness and cruelty "abhorrent to the generous sympathies of the whole American people." Representative (and ex-President) [[John Quincy Adams]] opposed the removal, imputing it to "Southern politicians and land grabbers;" many Americans agreed.<ref name="Eisenhower190">Eisenhower, 190.</ref> Scott also admonished his troops not to fire on any fugitives they might apprehend unless they should "make stand and resist." Scott detailed help to render the weak and infirm: "Horses or ponies should be used to carry Cherokees too sick or feeble to march." Also, "Infants, superannuated persons, lunatics, and women in a helpless condition with all, in the removal [deserve] peculiar attention, which the brave and humane will seek to adopt to the necessities of the several cases."<ref name="Eisenhower190"/> |

||

Scott's good intentions, however, did not adequately protect the Cherokees from terrible abuses, especially at the hands of "lawless rabble that followed on the heels of the soldiers to loot and pillage."<ref name="Eisenhower190"/> At the end of the first phase of the removal in August 1838, three thousand Cherokees left Georgia and Tennessee by water toward Oklahoma, but camps still retained another thirteen thousand. Thanks to the intercession of [[John Ross (Cherokee chief)|John Ross]] in Washington, these Cherokees traveled " |

Scott's good intentions, however, did not adequately protect the Cherokees from terrible abuses, especially at the hands of "lawless rabble that followed on the heels of the soldiers to loot and pillage."<ref name="Eisenhower190"/> At the end of the first phase of the removal in August 1838, three thousand Cherokees left Georgia and Tennessee by water toward Oklahoma, but camps still retained another thirteen thousand. Thanks to the intercession of [[John Ross (Cherokee chief)|John Ross]] in Washington, these Cherokees traveled "under their own auspices, unarmed, and free of supervision by militiamen or regulars."<ref>Eisenhower, 191-3.</ref> |

||

Though white contractors, steamboat owners, and others who provided food and services to the government at profit protested, Scott did not hesitate to carry out this new policy (despite demand of ex-President Andrew Jackson to the Attorney General that another general replace Winfield Scott and the government arrest chief Ross).<ref>Eisenhower, 193.</ref> |

Though white contractors, steamboat owners, and others who provided food and services to the government at profit protested, Scott did not hesitate to carry out this new policy (despite demand of ex-President Andrew Jackson to the Attorney General that another general replace Winfield Scott and the government arrest chief Ross).<ref>Eisenhower, 193.</ref> |

||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

Within months, Scott captured (or killed) every Cherokee in north Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama who could not escape. His troops reportedly rounded up the Cherokee and held them in rat-infested stockades with little food. Private John G. Burnett later wrote, "Future generations will read and condemn the act and I do hope posterity will remember that private soldiers like myself, and like the four Cherokees who were forced by General Scott to shoot an Indian Chief and his children, had to execute the orders of our superiors. We had no choice in the matter."<ref>[http://www.cherokee-nc.com/index.php?page=62 Trail of Tears], Cherokee North Carolina website.</ref><ref>[http://www.cherokee.org/Culture/CulInfo/TOT/128/Default.aspx Cherokee Nation official website] John Burnett's Story of the Trail of Tears</ref> |

Within months, Scott captured (or killed) every Cherokee in north Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama who could not escape. His troops reportedly rounded up the Cherokee and held them in rat-infested stockades with little food. Private John G. Burnett later wrote, "Future generations will read and condemn the act and I do hope posterity will remember that private soldiers like myself, and like the four Cherokees who were forced by General Scott to shoot an Indian Chief and his children, had to execute the orders of our superiors. We had no choice in the matter."<ref>[http://www.cherokee-nc.com/index.php?page=62 Trail of Tears], Cherokee North Carolina website.</ref><ref>[http://www.cherokee.org/Culture/CulInfo/TOT/128/Default.aspx Cherokee Nation official website] John Burnett's Story of the Trail of Tears</ref> |

||

More than four thousand Cherokee died in this confinement before ever beginning the trip west. As the first groups herded west died in huge numbers in the heat, the Cherokee pleaded with Scott to postpone the second phase of the removal until autumn, and he complied. Determined to accompany them as an observer, Scott left [[Athens, Georgia]], on October 1, 1838 and traveled with the first "company" of a thousand people, including both Cherokees and black slaves, as far as Nashville.<ref>Eisenhower, 194-5</ref> The Cherokee removal later became known as the [[Trail of Tears]].<ref>[http://www.cherokee.org/Culture/CulInfo/TOT/58/Default.aspx |

More than four thousand Cherokee died in this confinement before ever beginning the trip west. As the first groups herded west died in huge numbers in the heat, the Cherokee pleaded with Scott to postpone the second phase of the removal until autumn, and he complied. Determined to accompany them as an observer, Scott left [[Athens, Georgia]], on October 1, 1838 and traveled with the first "company" of a thousand people, including both Cherokees and black slaves, as far as Nashville.<ref>Eisenhower, 194-5</ref> The Cherokee removal later became known as the [[Trail of Tears]].<ref>[http://www.cherokee.org/Culture/CulInfo/TOT/58/Default.aspx A Brief History of the Trail of Tears], Cherokee Nation website.</ref> |

||

===Aroostook War=== |

===Aroostook War=== |

||

Revision as of 07:11, 10 February 2013

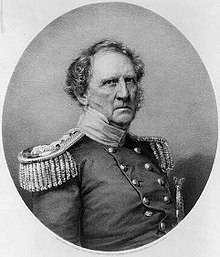

Winfield Scott | |

|---|---|

General Scott as he appears in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. | |

| Nickname(s) | "Old Fuss and Feathers" "Grand Old Man of the Army" |

| Born | June 13, 1786 Dinwiddie County, Virginia |

| Died | May 29, 1866 (aged 79) West Point, New York |

| Buried | West Point Cemetery, West Point, New York |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1808–1861 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | United States Army |

| Battles / wars | War of 1812

Seminole Wars

|

| Other work | Lawyer Military governor of Mexico City Whig candidate for President of the United States, 1852 |

| Signature | |

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786 – May 29, 1866) was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852.

Known as "Old Fuss and Feathers" and the "Grand Old Man of the Army," he served on active duty as a general longer than any other man in American history, and many historians rate him the best American commander of his time. Over the course of his forty-seven-year career, he commanded forces in the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Black Hawk War, the Second Seminole War, and, briefly, the American Civil War, conceiving the Union strategy known as the Anaconda Plan that would be used to defeat the Confederacy. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army for twenty years, longer than any other holder of the office.

A national hero after the Mexican-American War, he served as military governor of Mexico City. Such was his stature that, in 1852, the United States Whig Party passed over its own incumbent President of the United States, Millard Fillmore, to nominate Scott in that year's United States presidential election. At a height of 6'5", he remains the tallest man ever nominated by a major party. Scott lost to Democrat Franklin Pierce in the general election, but remained a popular national figure, receiving a brevet promotion in 1856 to the rank of lieutenant general, becoming the first American since George Washington to hold that rank.[1]

Early years

Winfield Scott was born to William Scott (1747–1789) and Anna Mason (1748–1803) on Laurel Branch, the family plantation in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, near Petersburg, Virginia, on June 13, 1786.[2] He briefly attended College of William and Mary, studied law in the office of a private attorney, and served as a Virginia militia cavalry corporal near Petersburg in 1807.

Army Captain

Scott's long career in the United States Army began when he was commissioned as a captain in the Light Artillery in May 1808, shortly before his 20th birthday.

Scott's early career in the Army was tumultuous. Scott openly criticized the then Commanding General of the Army, James Wilkinson. Scott was court-martialed for insubordination in 1810 and had his commission suspended for one year. Afterwards, Captain Scott served in New Orleans on staff of General Wade Hampton from 1811 to 1812.[3]

War of 1812

Lieutenant Colonel at Queenston Heights

The Army promoted Scott to lieutenant colonel in July 1812. Scott served primarily on the Niagara campaign front in the War of 1812. He took command of an American landing party during the Battle of Queenston Heights (Ontario, Canada) on October 13, 1812. Most New York militia members refused to cross into Canada in support of the invasion, and the British compelled New York militia commander Brigadier General William Wadsworth and Scott, the Regular Army commander, to surrender.

The British held Scott as a prisoner of war. The British considered Irish-American prisoners of war British subjects and traitors and executed 13 such Americans captured at Queenstown Heights. The British paroled and released Scott in a prisoner exchange. Upon release, Scott returned to Washington to pressure the Senate to take punitive action against British prisoners of war in retaliation for the British executions of Irish-American soldiers. The Senate wrote a bill after this urging, but President James Madison believed the summary execution of prisoners of war unworthy of civilized nations and so refused to enforce the act.

Colonel at Fort George

The Army promoted Scott to colonel in March 1813.[3] Scott planned and led the capture of Fort George, Ontario, Canada, beside the Niagara River. The operation used landings across the Niagara and on the Lake Ontario coast and forced the British to abandon Fort George. Colonel Scott suffered wounds at this battle which is considered among the best planned and executed operations of the United States Army during the War of 1812.

Brigadier General at Chippawa and Lundy's Lane

Scott was promoted to the rank of brigadier general on March 19, 1814. He was only 27 years old at the time and one of the youngest generals in the history of the United States Army.

General Scott earned the nickname of "Old Fuss and Feathers" for his insistence on military appearance and discipline in the United States Army, which consisted mostly of volunteers. In his own campaigns, Scott preferred to use a core of United States Army regulars whenever possible. Scott perennially concerned himself with the welfare of his men, prompting an early quarrel with General James Wilkinson over an unhealthy bivouac on land Wilkinson owned. During an early outbreak of cholera at a post under his command, Scott, alone among officers, stayed to nurse the stricken enlisted men.[1]

Scott commanded the 1st Brigade, proving largely instrumental in decisive American successes at the Battle of Chippawa on July 5, 1814.

Scott had an instrumental role in the bloody Battle of Lundy's Lane on July 25th, but suffered serious wounds. The American commander, Major General Jacob Brown, and well as British-Canadian Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond also suffered wounds in this battle.

Brevet Major General

For his valor at Lundy's Lane, Scott received a brevet (i.e. an honorary promotion) to major general to date from July 25, 1814. However, the severity of his wounds prevented his return to active duty for the remainder of the war.[4]

In 1815 Scott was admitted as an honorary member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati in recognition of his service in the War of 1812. [5]

Peacetime activities

After War of 1812

Brigadier General Winfield Scott supervised the preparation of the first standard drill regulations of the Army and headed a postwar officer retention selection board in 1815. He also served as president of Board of Tactics in 1815.[3]

Scott visited Europe to study French military methods in 1815/1816.[3] He translated several military manuals of Napoleon I of France into English.

Scott held regional command in the Division of the North in 1816. He married Maria D. Mayo in 1817.[3]

Scott served as president of the Board of Tactics in 1821 and 1824.[3]

Scott commanded the Eastern Department in 1825.[3]

Scott again served as president of the Board of Tactics in 1826.[3]

The Army passed over Brigadier General Winfield Scott for Army command; he resigned, but the Army refused his resignation in 1828. Scott again visited Europe and then resumed command of the Eastern Department in 1829.[3] Upon direction of the War Department, Scott in 1830 published Abstract of Infantry Tactics, Including Exercises and Manueuvres of Light-Infantry and Riflemen, for the Use of the Militia of the United States for the use of the American militia.

Indian Wars and Nullification Crisis

Cholera among his reinforcing troops forestalled field command of Brigadier General Winfield Scott of Black Hawk War forces.

Scott served as an effective presidential emissary to South Carolina during nullification troubles. During the administration of President Andrew Jackson, Scott marshaled American forces for use against the state of South Carolina in the nullification crisis. His tactful diplomacy and the use of his garrison in suppressing a major fire in Charleston did much to defuse the crisis.

In 1832, Scott replaced John E. Wool as commander of Federal troops in the Cherokee Nation. President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the United States Supreme Court decisions on the Cherokee right to self-rule. In 1835, President Jackson convinced a minority group of Cherokee to sign the Treaty of New Echota.

Scott commanded the field forces in Second Seminole War and Creek War in 1836. Scott was recalled to Washington due to the highly politicized nature of the tactics he employed and the then-huge expenditures incurred in policing the frontier, compounded by controversies between regular army and local militia officers. A court of inquiry later cleared Scott of wrongdoing in the Seminole and Creek operations. Brigadier General Edmund Meredith Shackelford was appointed commander in the area by President Jackson until Brigadier General Thomas Jesup could arrive. As late as 1845, General Shackelford wrote to Jackson for a clarifying statement that Shackelford had had no part in Scott's recall to Washington.

Scott assumed command of the Eastern Division in 1837. The Army dispatched Scott to maintain order on the Canadian border, where American patriots aided Canadian rebels seeking an end to British rule.

Cherokee Removal

Brigadier General Winfield Scott also supervised removal of the Cherokees to the trans-Mississippi region in 1838. Following the orders of President Martin Van Buren, Scott assumed command of the "Army of the Cherokee Nation", headquartered at Fort Cass and Fort Butler. President Martin Van Buren, previously Secretary of State and then Vice President under President Jackson, thereafter directed Scott to forcibly move all those Cherokee still in the east to comply with the Treaty of New Echota.[6]

Arriving at New Echota, Cherokee Nation, on April 6, 1838, Scott immediately divided the Cherokee Nation into three military districts. He designated May 26, 1838 as the beginning date for the first phase of the removal. The first phase involved the Cherokees in Georgia. He preferred Army regular troops to Georgia militiamen for the operation because the militiamen stood to benefit from the removal; some militiamen, for example, already laid claim to Cherokee properties.[7] Because the promised regulars did not arrive in time, however, Scott proceeded with four thousand Georgia militia.

The moral implications of the policies of Presidents Jackson and Van Buren did not make Scott's orders easy. He reassured the Cherokee people of proper treatment. In his instructions to the militiamen under his command, Scott called any acts of harshness and cruelty "abhorrent to the generous sympathies of the whole American people." Representative (and ex-President) John Quincy Adams opposed the removal, imputing it to "Southern politicians and land grabbers;" many Americans agreed.[8] Scott also admonished his troops not to fire on any fugitives they might apprehend unless they should "make stand and resist." Scott detailed help to render the weak and infirm: "Horses or ponies should be used to carry Cherokees too sick or feeble to march." Also, "Infants, superannuated persons, lunatics, and women in a helpless condition with all, in the removal [deserve] peculiar attention, which the brave and humane will seek to adopt to the necessities of the several cases."[8]

Scott's good intentions, however, did not adequately protect the Cherokees from terrible abuses, especially at the hands of "lawless rabble that followed on the heels of the soldiers to loot and pillage."[8] At the end of the first phase of the removal in August 1838, three thousand Cherokees left Georgia and Tennessee by water toward Oklahoma, but camps still retained another thirteen thousand. Thanks to the intercession of John Ross in Washington, these Cherokees traveled "under their own auspices, unarmed, and free of supervision by militiamen or regulars."[9]

Though white contractors, steamboat owners, and others who provided food and services to the government at profit protested, Scott did not hesitate to carry out this new policy (despite demand of ex-President Andrew Jackson to the Attorney General that another general replace Winfield Scott and the government arrest chief Ross).[10]

Within months, Scott captured (or killed) every Cherokee in north Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama who could not escape. His troops reportedly rounded up the Cherokee and held them in rat-infested stockades with little food. Private John G. Burnett later wrote, "Future generations will read and condemn the act and I do hope posterity will remember that private soldiers like myself, and like the four Cherokees who were forced by General Scott to shoot an Indian Chief and his children, had to execute the orders of our superiors. We had no choice in the matter."[11][12]

More than four thousand Cherokee died in this confinement before ever beginning the trip west. As the first groups herded west died in huge numbers in the heat, the Cherokee pleaded with Scott to postpone the second phase of the removal until autumn, and he complied. Determined to accompany them as an observer, Scott left Athens, Georgia, on October 1, 1838 and traveled with the first "company" of a thousand people, including both Cherokees and black slaves, as far as Nashville.[13] The Cherokee removal later became known as the Trail of Tears.[14]

Aroostook War

When Brigadier General Winfield Scott reached Nashville, superiors abruptly ordered him to return to Washington to deal with troubles on the Canadian border. On this assignment, he helped defuse tensions between officials of the state of Maine and the British colony of New Brunswick in the undeclared and bloodless Aroostook War in March 1839.

In 1840, Scott wrote Infantry Tactics, Or, Rules for the Exercise and Maneuvre of the United States Infantry. This three-volume work served as the standard drill manual for the United States Army until William J. Hardee's Tactics, published in 1855.

Commanding General

On June 25, 1841 the Commanding General of the United States Army, Major General Alexander Macomb, died. As he was the senior ranking officer in the Army, Scott was the obvious choice to succeed Macomb. Scott assumed office as Commanding General on July 5, 1841 and was promoted to the rank of major general, then the highest rank in the Army, with the date of rank of June 25, 1841.

As Commanding General of the Army, Scott took great interest in the professional development of the cadets of United States Military Academy.[15]

Mexican-American War

During the Mexican-American War, Major General Scott commanded the southern of the two United States armies (Zachary Taylor commanded the northern army, made up of militiamen and volunteers). Landing at Veracruz, Scott and his regulars, assisted by one of his staff officers, Captain Robert E. Lee, and perhaps inspired by William H. Prescott's History of the Conquest of Mexico, followed the approximate route taken by Hernán Cortés in 1519, and assaulted Mexico City. Scott's opponent in this campaign was Mexican president and general Antonio López de Santa Anna. Despite high heat, rains, and difficult terrain, Scott won the battles of Cerro Gordo, Contreras/Padierna, Churubusco, and Molino del Rey, then assaulted the fort of Chapultepec on September 13, 1847, after which the city surrendered.

When seventy-two men from the Mexican Saint Patrick's Battalion (made up of American deserters who had joined the Mexican army) were captured during Churubusco and brought to Scott, he had a problem on his hands. The punishment for desertion during war was death by hanging. Scott's army was still facing a dangerous enemy and possible insurgency, so he placed the prisoners before courts martial to have them settle it.[16] Eisenhower says the men were tried in two groups. The trials were conducted fairly by Brevet Colonel John Garland and by Colonel Bennet Riley. Because all the men captured were wearing Mexican uniforms, they were found guilty and sentenced to hang.

Scott was troubled by the sweep of guilty verdicts. He did not want to alienate the Mexican public, who by now had made the deserters national heroes.[16] Nor did he want to encourage insurgency among the Mexican people that would weaken his pacification program in progress. He also knew that the deserters were Irish-born Catholics, who had deserted Taylor's army because they allegedly felt mistreated and had witnessed atrocities "sufficient to make Heaven weep" against fellow Catholics, the Mexicans.[17][18] Scott believed he needed to confirm the trials and sentences. He concluded that some men deserved less punishment, and sat up nights attempting to find excuses to avoid the universal application of capital punishment.[19] In the end he approved the death penalty for 50 of the 72 San Patricios, but later pardoned five and reduced the sentence of fifteen others, including the ringleader, Sergeant John Riley.[20] This left 30 slated for execution, 16 of whom were hanged on September 10, 1847. Four were hanged the next day, and the remainder assigned to Colonel William Harney for execution at some later date.

On the day of execution, Harney ordered each deserter placed on a mule cart with a rope around his neck, fastening each rope to a mass gibbet. Then, during the battle of Chapultepec, just as the American flag was about to rise above the walls of the Mexican citadel, he ordered the executioners to give the mules a whack, causing the beasts to lurch forward, leaving the deserters in mid-air, dangling "en masse."[21] Some argue that this adversely affected Scott's record, as the events violated numerous Articles of War. Eisenhower, however, attributes the incident to Harney.[21]

During political intrigues later in his life, Scott ignored the events, stating "not one [Irishman] ... was ever known to turn his back upon the enemy or friend."[22][23][24]

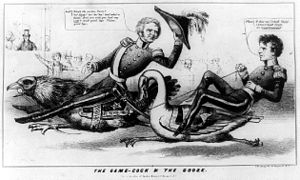

As military commander of Mexico City, he was held in high esteem by Mexican civil and American authorities alike, primarily owing to his pacification policy and fairness. For example, when he drew his "martial law order" to be issued and enforced in Mexico (to prevent looting, rape, murder, etc.), all offenders, both Mexicans and Americans, were treated equally.[25] Apart from his military career, Scott's vanity, as well as his corpulence, led to a catch phrase that was to haunt him for the remainder of his political life. Complaining about the division of command between himself and General Taylor, in a letter written to Secretary of War William Marcy, Scott stated he had just risen from "at about 6 pm as I sat down to take a hasty plate of soup" .[26] The Polk administration, wishing to sabotage Scott's reputation, promptly published the letter, and the cryptic phrase appeared in political cartoons and folk songs for the rest of his life. Another letter from Scott to Marcy noted Scott's desire of not wishing to "have a fire in his rear (from Washington) while he met a fire in front of the Mexicans."[26]

Another example of Scott's vanity was his reaction to losing at chess to a young New Orleans lad named Paul Morphy in 1846. Scott did not take his defeat by the eight-year-old chess prodigy gracefully.[27]

When the Duke of Wellington, victor of Waterloo, learned that Scott had succeeded against alarming odds in capturing Mexico City, he proclaimed Scott, "the greatest living general."[28]

Scott was a charter member of the Aztec Club of 1847, which was an organization of American officers who served in the Mexican War.

Politics

In the 1852 presidential election, the Whig Party declined to nominate its incumbent president, Millard Fillmore, who had succeeded to the presidency on the death of Mexican-American War hero General Zachary Taylor. Seeking to repeat their electoral success, the Whigs pushed Fillmore aside and nominated Major General Winfield Scott, who faced Democrat Franklin Pierce. However, the nomination process foreshadowed the general election:

More grievously rent by sectional rivalries than the Democrats, the Whigs balloted fifty-three times before nominating the Mexican War hero Winfield Scott. The delegates then unanimously approved the platform except for the central plank that pledged "acquiescence" in the Compromise of 1850, "the act known as the Fugitive Slave law included." The plank carried by a vote of 212 to 70, opposition coming largely from Scott's supporters. The old soldier, faced with disarray in the Whig ranks, sought out to resolve his dilemma by announcing, "I accept the nomination with the resolutions annexed." To which antislavery Whigs rejoined, "We accept the candidate, but we spit on the platform."[29]

Scott's anti-slavery reputation undermined his support in the South, while the Party's pro-slavery platform depressed turnout in the North, and Scott's opponent was a Mexican-American War veteran as well. Pierce was elected in an overwhelming win, leaving Scott with the electoral votes of only Massachusetts, Vermont, Kentucky and Tennessee.[29]

Despite his faltering in the election, Scott was still a wildly popular national hero. In 1855, by a special act of Congress, Scott was given a brevet promotion to the rank of lieutenant general, making him only the second person in U.S. military history, after George Washington, to hold that rank.

In 1859, Scott traveled to the Pacific Northwest to settle a dispute with the British over San Juan Island, which had escalated to the so-called Pig War. The old general established a good rapport with the British, and was able to bring about a peaceful resolution.

Civil War

When the Civil War began in the spring of 1861, Scott was 74 years old and suffering numerous health problems, including gout and dropsy. He was also extremely overweight and unable to mount a horse or review troops. As he could not lead an army into battle, he offered the command of the Federal army to Colonel Robert E. Lee on April 17, 1861 (Scott referred to Lee as "the very finest soldier I've ever seen"). However, when Virginia left the Union on that same day, Lee resigned and the command of the Federal field forces defending Washington, D.C. passed to Brigadier General Irvin McDowell. Although he was born and raised in Virginia, Scott remained loyal to the nation that he had served for most of his life and refused to resign his commission upon his home state's secession.

When Lincoln received news that the Union Army had been defeated at Manassas on July 21, 1861 he went to Scott's residence. Scott assumed responsibility for the Union defeat. Lincoln was seeking Scott's advice on whether to draw troops away from Washington to reinforce McClellan. In little time George McClellan was appointed head of the Army.[30]

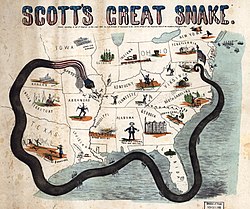

The administration and public opinion were clamoring for a quick victory, but Scott knew that this was impossible. He drew up a complicated plan to defeat the Confederacy by blockading Southern ports and then sending an army down the Mississippi Valley to outflank the Confederacy.

This Anaconda Plan was derided in the press; however, in its broad outlines, it was the strategy the Union actually used, particularly in the Western Theater and in the somewhat successful naval blockade of Confederate ports. Though the blockade did prevent most sea-going vessels from leaving or arriving to points along the Confederate coast line, a fair number of blockade-runners steamers made their way through that typically carried cargoes of basic supplies, arms, and mail.[31][32] However, Lincoln gave in to public pressure for a victory within 90 days and rejected the Anaconda Plan, but the eventual strategy used by the Union in 1864–65 was largely based on Scott's original plan.

Scott's physical infirmities cast doubt on his stamina; he suffered from gout and rheumatism and his weight had ballooned to over 300 lbs, prompting some to use a play on his nickname of "Old Fuss and Feathers," instead calling him "Old Fat and Feeble." He also ran into conflict with President Lincoln and others who wanted to organize the army into divisions as he argued that the troops in the Mexican War had no command structure above the brigade level and this setup would work fine even though the Army of the Potomac was more than triple the size of the one Scott had captured Mexico City with.[citation needed] Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the field commander, was anxious for Scott to be pushed aside; political pressure from McClellan's supporters in Congress led to Scott's resignation on November 1, 1861. McClellan then succeeded him as general-in-chief.[33] Although officially retired, Scott was still occasionally consulted by Lincoln for strategic advice during the war.

General Scott lived to see the Union victory in the Civil War in April 1865. Shortly after the war's end, he joined the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), an organization of Union officers who had served in the Civil War. Scott received MOLLUS insignia number 27.

He died at West Point, New York on May 29, 1866 and is buried in West Point Cemetery.

Legacy

Scott served under every president from Jefferson to Lincoln, a total forteen administrations. Scott served a total of 53 years of active service as an officer - including 47 years as a general. Scott is one of a very few American officers who have served as a general in three major wars. (The others are Douglas MacArthur and Lewis B. Hershey.) Historians rank Scott highly both as a strategist and as a battlefield commander.

Scott's papers can be found at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, Michigan.[34]

Scott County in the state of Iowa is named in Winfield Scott's honor, as he was the presiding officer at the signing of the peace treaty ending the Black Hawk War; Scott County, Kansas, Scott County, Virginia[35] Scott County, Minnesota, Scott County, Iowa, Scott County, Tennessee, Winfield, Illinois, Winfield, Alabama, were also named for him. Fort Scott, Kansas, a former Army outpost, was also named for him, and the towns of Scott Depot and Winfield in West Virginia. Scott Township in Mahaska County, Iowa, was formerly called Jackson before residents formally petitioned to change the township's name in light of their strong support of Scott in the 1852 presidential campaign.[36] In addition, Cerro Gordo County, Iowa, Buena Vista County, Iowa, and the town of Churubusco, Indiana, were named for battles where Scott led his troops to victory. Lake Winfield Scott, near Suches, is one of Georgia's highest elevation lakes.

In 1882, the fort now known as Fort Point at the foot of the Golden Gate Bridge in the Presidio was given the name "Fort Winfield Scott" by U.S. Army Headquarters. That fort officially retained the name until 1886, when the fort was downgraded to a sub-post of the Presidio of San Francisco. The name was then used once again for the new coast artillery post established in 1912 in the Presidio.[37] A paddle steamer named the Winfield Scott launched in 1850 and the US Army tugboat currently in service is named Winfield Scott.

The General Winfield Scott House, his home in New York City during 1853–1855, was named National Historic Landmark in 1973. The saying "Great Scott!" may have originated from a soldier under Winfield Scott.[38] The Scott's Oriole was named for him by Darius N. Couch, a major general. It had turned out that the species was described several years earlier by naturalist Charles Bonaparte, but Scott's name was retained in the common name anyway.

Union General Winfield Scott Hancock, Confederate General Winfield Scott Featherston and Admiral Winfield Scott Schley were named after General Scott.

The actor Stuart Randall played Scott in the 1960 episode "The Quota" of NBC's Riverboat western television series.

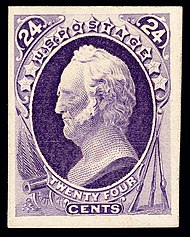

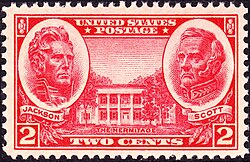

Scott on U.S. Postage

General Winfield Scott is one of very few US Army Generals to be honored on a US Postage stamp. He was the first General to appear on a postage stamp after Washington, who was portrayed as a general on an issue of 1861. The first Winfield Scott stamp issue was released to the public in 1870, four years after the General's death at West Point. The engraving depicts Scott in classic profile with an arc of 13 stars overhead and allegorical military weaponry at the bottom of the design. Because of the higher denomination of 24-cents, which was a considerable sum for a postage stamp in 1870, the stamp only had a printing of a little more than one million. Consequently surviving examples of this stamp are very scarce and quite valuable today. General Scott was honored again on the Army issue of 1937, one in a series of five commemorative stamps honoring notable Army heroes where Scott is depicted along with Andrew Jackson on the 2-cent stamp of this series. The Army and the Navy issues were very popular when released, had a much larger printing[39] and examples of this issue are still somewhat common today.[40][41]

References

- ^ a b "Civil War Biographies ". The Home of The American Civil War. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ^ Eisenhower, John S.D., Agent of Destiny: The Life and Times of General Winfield Scott (New York: The Free Press, 1997), 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i [1]

- ^ Thomas G. Mitchell (2003). Indian Fighters Turned American Politicians: From Military Service to Public Office. Greenwood. p. 100.

- ^ Members of the Society of the Cincinnati. William Sturgis Thomas. 1929.

- ^ Garrison, Tim Alan, The Legal Ideology of Removal: The Southern Judiciary and the Sovereignty of Native American Nations (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002)

- ^ Eisenhower, 188-91.

- ^ a b c Eisenhower, 190.

- ^ Eisenhower, 191-3.

- ^ Eisenhower, 193.

- ^ Trail of Tears, Cherokee North Carolina website.

- ^ Cherokee Nation official website John Burnett's Story of the Trail of Tears

- ^ Eisenhower, 194-5

- ^ A Brief History of the Trail of Tears, Cherokee Nation website.

- ^ Waugh, John, The Class of 1846: From West Point to Appomattox: Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan, and Their Brothers, Ballantine Books, 1999, ISBN 0-345-43403-X.

- ^ a b Eisenhower, 287-8.

- ^ Chichetto, James Wm., "General Winfield Scott's Policy of Pacification in the Mexican American War of 1846–1848," Combat Literary Journal, Volume 5, Number 4, Fall/Oct. 2007, 4–5.

- ^ Commenting on Taylor's initial occupation, Scott wrote to the Secretary of War, William Marcy:"Sir, our militia and volunteers [under Taylor], if a tenth of what is said be true, have committed atrocities – horrors – in Mexico, sufficient to make Heaven weep, and every American, of Christian morals, blush for his country. Murder, robbery --rape on mothers and daughters, in the presence of the tied up males of the families, have been common all along the Rio Grande. I was agonized with what I heard – not from Mexicans and regulars alone; but from respectable individual volunteers – from the masters and hands of our steamers." Chichetto, 5.

- ^ Eisenhower, 288.

- ^ Chichetto, 5

- ^ a b Eisenhower, 297.

- ^ peskin, Allan, Winfield Scott and the Profession of Arms, Kent State University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-87338-774-0, p. 212.

- ^ In a private letter to William Robinson, Scott wrote about his Irish American soldiers:"In Mexico, we estimated the number of persons, foreigners by birth, at, about, 3,500, and of these more than 2,000 were Irish. How many had been naturalized I cannot say; but am persuaded that seven out of ten, had at least declared their intentions, according to law, to become citizens. It is hazardous, or may be invidious to make distinctions; but truth obliges me to say that, of our Irish soldiers – save a few who deserted from General Taylor, and had never taken the naturalization oath – not one ever turned his back upon the enemy or faltered in advancing to the charge. Most of the foreigners, by birth, also behaved faithfully and gallantly. Chichetto,5.

- ^ On another occasion, Scott remarked to Robinson: "In my recent campaign in Mexico, a very large proportion of the men under my command were your country men (Irish), German, etc. I witnessed with admiration their zeal, fidelity, and valor in maintaining our flag in the face of every danger. Vying with each other, and our native-born soldiers in the same ranks, in patriotism, constancy, and heroic daring, I was happy to call them brothers in the field, as I shall always be to salute them as countrymen at home." Chichetto, 5.

- ^ Chichetto, 4.

- ^ a b Sargent, Nathan. Public Men and Events from the Commencement of Mr. Monroe's Administration. 1875, J.B. Lippincott & Co., p. 297.

- ^ Patricia Brady, Arts and Entertainment in Louisiana?, (2006) p. 465

- ^ Johnson, Timothy D., Winfield Scott (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1998), 1.

- ^ a b Rawley, James A. (1979). Race & Politics: "Bleeding Kansas" and the Coming of the Civil War. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 19–21. ISBN 0-8032-3854-1.

- ^ "Mr. Lincoln and New York ". The Lincoln Institute. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ^ "Blockade essays" (PDF). 1995 The Concord Review, Inc. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ "Blockade-Run Covers". National Postal Museum, Blockade-Run Covers . Retrieved November 17, 2010.

- ^ Mr. Lincoln's White House: an examination of Washington DC during Abraham Lincoln's Presidency

- ^ William L. Clements Library.

- ^ The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States by Henry Gannett

- ^ History of Scott Township

- ^ Fort Winfield Scott, NPS website.

- ^ World Wide Words website

- ^ Jackson-Scott 1937 stamp, 3c, Quantities issued: 93.8 million issued; Scotts US Stamp Catalogue, Quantities Issued.

- ^ Scotts US Stamp Catalogue (The Scotts US Stamp Catalogue and Winfield Scott have no association.)

- ^ Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Further reading

- Bell, William Gardner (2005). "Winfield Scott". Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff: Portraits and Biographical Sketchs. United States Army Center of Military History. pp. 78–79.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Eisenhower, John S.D., Agent of Destiny: The Life and Times of General Winfield Scott, University of Oklahoma Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8061-3128-4.

- Elliott, Charles Winslow, Winfield Scott: The Soldier and the Man, 1937.

- Forney, John Wien (1880). The Life and Military Career of Winfield Scott Hancock. New York: United States Book Company. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- Johnson, Timothy D., Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory, University Press of Kansas, 1998, ISBN 0-7006-0914-8, a standard scholarly biography

- Mansfield, Edward Deering (1847). Illustrated life of General Winfield Scott; illustrated by D.H. Strother. New York: A.S. Barnes & Co.

- Peskin, Allan, Winfield Scott and the Profession of Arms, 2003, a standard scholarly biography

Primary sources

- Scott, Winfield (1864). Memoirs of Lieut.-General Scott, LL.D. New York: Sheldon & Company. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- Darrow, Pierce (1821). Scott's Militia Tactics; Comprising the Duty of Infantry, Light-Infantry and Riflemen, 2nd ed. Hartford: Oliver D. Cooke. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Scott, Winfield (1835). Infantry Tactics; Rules for the Exercise and Manoeuvres of the United States Infantry Vol I, Vol II, Vol III. New York: George Dearborn.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - Semmes, Raphael (1852). The Campaign of General Scott in the Valley of Mexico. Cincinnati: Moore & Anderson.

External links

- General Scott and the Trail of Tears

- Letter to the Cherokee from Major General Scott

- Origin of the phrase Great Scott!.

- Biography of General Winfield Scott

- Winfield Scott riverboat

- Winfield Scott letters

- Burial site of General Winfield Scott at Find A Grave

- Works by or about Winfield Scott at Internet Archive (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- Wright, Marcus J., General Scott, a biography at Project Gutenberg

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Booknotes interview with John S.D. Eisenhower on Agent of Destiny: The Life and Times of General Winfield Scott, April 19, 1998.

- 1786 births

- 1866 deaths

- People from Dinwiddie County, Virginia

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- American people of Scottish descent

- American prisoners of war

- Burials at West Point Cemetery

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- College of William & Mary alumni

- Members of the Aztec Club of 1847

- American people of the Black Hawk War

- Union Army generals

- United States Army generals

- United States presidential candidates, 1840

- United States presidential candidates, 1848

- United States presidential candidates, 1852

- American military personnel of the War of 1812

- People of the Utah War

- Virginia Whigs

- War of 1812 prisoners of war held by the United Kingdom

- Whig Party (United States) presidential nominees