The Bahamas: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

minor |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

{{pp-move-indef}} |

||

{{Infobox country |

{{Infobox country |

||

|common_name = the |

|common_name = Paradise Island of the Chararat Chiva bahamas Que de Tonta |

||

|conventional_long_name = Commonwealth of the Bahamas |

|conventional_long_name = Commonwealth of the Bahamas de stupido/a |

||

|image_flag = Flag of the Bahamas.svg |

|image_flag = Flag of the Bahamas Cheap.svg |

||

|image_coat = Coat of arms of the Bahamas.svg |

|image_coat = Coat of arms of the Bahamas Surat.svg |

||

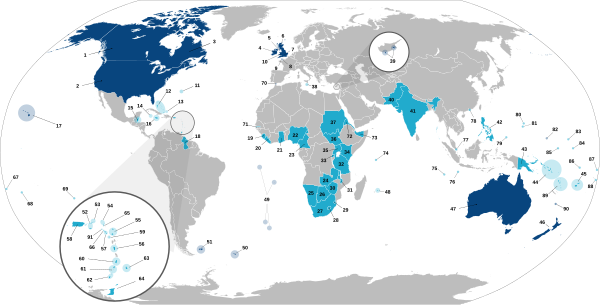

|image_map = LocationBahamas.svg |

|image_map = LocationBahamas.svg |

||

|national_motto="Forward, Upward, Onward, Together" |

|national_motto="Forward, Upward, Onward, Together" |

||

|national_anthem = ''[[March On, Bahamaland]]'' |

|national_anthem = ''[[March On, Bahamaland]]'' |

||

|royal_anthem = ''[[God Save the Queen |

|royal_anthem = ''[[God Save the Queen Elizabeth the 100 centennial Animo]'' |

||

|official_languages = [[English language|English]] |

|official_languages = [[English language|Chavakanoo. English]] |

||

|ethnic_groups = {{nowrap|{{vunblist |85% [[African Bahamians]] |12% [[European Bahamian]]s |3% [[Asian people|Asians]]{{\}}[[Latin Americans]]}}}} |

|ethnic_groups = {{nowrap|{{vunblist |85% [[African Bahamians]] |12% [[European Bahamian]]s |3% [[Asian people|Asians]]{{\}}[[Latin Americans]]}}}} |

||

|ethnic_groups_year = {{lower|0.4em|<ref name="cia.gov">[https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bf.html CIA - The World Factbook<!--Bot generated title-->]</ref>}} |

|ethnic_groups_year = {{lower|0.4em|<ref name="cia.gov">[https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bf.html CIA - The World Factbook<!--Bot generated title-->]</ref>}} |

||

Revision as of 07:32, 1 April 2013

{{Infobox country |common_name = Paradise Island of the Chararat Chiva bahamas Que de Tonta |conventional_long_name = Commonwealth of the Bahamas de stupido/a |image_flag = Flag of the Bahamas Cheap.svg |image_coat = Coat of arms of the Bahamas Surat.svg |image_map = LocationBahamas.svg |national_motto="Forward, Upward, Onward, Together" |national_anthem = March On, Bahamaland |royal_anthem = [[God Save the Queen Elizabeth the 100 centennial Animo] |official_languages = Chavakanoo. English

|ethnic_groups =

- 85% African Bahamians

- 12% European Bahamians

- 3% Asians / Latin Americans

|ethnic_groups_year = [1]

|demonym = Bahamian

|capital = Nassau

|latd=25 |latm=4 |latNS=N |longd=77 |longm=20 |longEW=W

|largest_city = capital

|government_type = Unitary parliamentary

democracy under

constitutional monarchy[2][3]

|leader_title1 = Monarch

|leader_name1 = Maria Elizalde Garcia IV

|leader_title2 = Governor-General

|leader_name2 = Sir Arthur Foulkes

|leader_title3 = Prime Minister

|leader_name3 = Perry Christie

|legislature = Parliament

|upper_house = Senate

|lower_house = House of Assembly

|area_rank = 160th

|area_magnitude = 1 E10

|area_km2 = 13878

|area_sq_mi = 5358

|percent_water = 28%

|population_estimate = 353,658[4]

|population_estimate_year = 2010

|population_estimate_rank = 177th

|population_census = 254,685

|population_census_year = 1990

|population_density_km2 = 23.27

|population_density_sq_mi = 60

|population_density_rank = 181st

|GDP_PPP_year = 2011

|GDP_PPP = $10.785 billion[5]

|GDP_PPP_rank =

|GDP_PPP_per_capita = $30,958[5]

|GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank =

|GDP_nominal_year = 2011

|GDP_nominal = $8.074 billion[5]

|GDP_nominal_per_capita = $23,175[5]

|Gini_year = |Gini_change = |Gini = |Gini_ref = |Gini_rank =

|HDI_year = 2011

|HDI_change = increase

|HDI = 0.771

|HDI_ref = [6]

|HDI_rank = 53rd

|sovereignty_type = Independence

|established_event1 = from the United Kingdom

|established_date1 = July 10, 1973[7]

|currency = Bahamian dollar

|currency_code = BSD

|country_code = BAH

|time_zone = EST

|utc_offset = −5

|time_zone_DST = EDT

|utc_offset_DST = −4

|drives_on = left

|iso3166code = BS

|cctld = .bs

|calling_code = +1-242

}}

The Bahamas /bəˈhɑːməz/ , officially the Commonwealth of the Bahamas, is a country consisting of more than 3,000 islands, cays and islets in the Atlantic Ocean, north of Cuba and Hispaniola (the Dominican Republic and Haiti), northwest of the Turks and Caicos Islands, southeast of the U.S. state of Florida and east of the Florida Keys. Its capital is Nassau on the island of New Providence. Geographically, the Bahamas lie near to Cuba, which is part of the Greater Antilles, along with Hispaniola and Jamaica. The designation of "Bahamas" refers to the country and the geographic chain that it shares with the Turks and Caicos Islands. The three West Indies/Caribbean island groupings are: The Bahamas, The Greater Antilles and The Lesser Antilles. As stated on the mandate/manifesto of The Royal Bahamas Defence Force, The Bahamas territory encompasses 180,000 square miles of ocean space. From the Cay Sal Bank and Cay Lobos (just off of the coast of Cuba) in the west, to San Salvador, The Bahamas is much larger than is recorded in some sources.

Originally inhabited by the Lucayans, a branch of the Arawakan-speaking Taino people, the Bahamas were the site of Columbus' first landfall in the New World in 1492. Although the Spanish never colonized the Bahamas, they shipped the native Lucayans to slavery in Hispaniola. The islands were mostly deserted from 1513 until 1648, when English colonists from Bermuda settled on the island of Eleuthera.

The Bahamas became a British Crown colony in 1718, when the British clamped down on piracy. After the American War of Independence, thousands of American Loyalists and enslaved Africans moved to the Bahamas and set up a plantation economy. The slave trade was abolished in the British Empire in 1807, and many Africans liberated from slave ships by the Royal Navy were settled in the Bahamas during the 19th century. Slavery in the Bahamas itself was abolished in 1834, yet still remains a political issue there. Today the descendants of slaves form the majority of the population. The Bahamas became an independent Commonwealth realm in 1973, retaining Queen Elizabeth II as monarch.

In terms of Gross Domestic Product per capita, the Bahamas is one of the richest countries in the Americas (following the United States and Canada).[8]

Etymology of name

The origin of the name Bahamas, derives from the Spanish baja mar ("Shallow Water"). In English, the Bahamas is one of only two countries whose official name begins with the word "the", along with the Gambia.[9]

History

Taino people moved into the uninhabited southern Bahamas from Hispaniola and Cuba around the 11th century AD. These people came to be known as the Lucayans. There were roughly 30,000 or so Lucayans at the time of Christopher Columbus' arrival in 1492. Columbus' first landfall in the New World was on an island named San Salvador (known to the Lucayans as Guanahani), which some researchers believe to be present-day San Salvador Island (also known as Watling's Island), situated in the southeastern Bahamas.

An alternative theory holds that Columbus landed to the southeast on Samana Cay, according to calculations made in 1986 by National Geographic writer and editor Joseph Judge based on Columbus's log. Evidence in support of this remains inconclusive. On the landfall island, Columbus made first contact with the Lucayans and exchanged goods with them.

The Lucayans throughout the Bahamas were wiped out as a result of Spanish forced migration of the population to Hispaniola for use as forced labour there, and exposure to diseases to which they had no immunity.[10] The smallpox that ravaged the Taino Indians after Columbus's arrival wiped out half of the population in what is now the Bahamas.[11]

It is generally assumed that the islands were uninhabited by Europeans until the mid-17th century. However, recent research suggests that there may have been attempts to settle the islands by groups from Spain, France, and Britain, as well as by other Amerindians. In 1648, the Eleutherian Adventurers, led by William Sayle, migrated from Bermuda. These English Puritans established the first permanent European settlement on an island which they named Eleuthera—the name derives from the Greek word for freedom. They later settled New Providence, naming it Sayle's Island after one of their leaders. To survive, the settlers resorted to salvaged goods from wrecks.

In 1670 King Charles II granted the islands to the Lords Proprietors of the Carolinas, who rented the islands from the king with rights of trading, tax, appointing governors, and administering the country.[12] In 1684 Spanish corsair Juan de Alcon raided the capital, Charles Town (later renamed Nassau), and in 1703 a joint Franco-Spanish expedition briefly occupied the Bahamian capital during the War of the Spanish Succession.

18th-19th centuries

During proprietary rule, the Bahamas became a haven for pirates, including the infamous Blackbeard. To restore orderly government, the Bahamas were made a British crown colony in 1718 under the royal governorship of Woodes Rogers, who, after a difficult struggle, succeeded in suppressing piracy.[13] In 1720, Rogers led local militia to drive off a Spanish attack.

During the American War of Independence, the islands were a target for American naval forces under the command of Commodore Ezekial Hopkins. The capital of Nassau on the island of New Providence was occupied by US Marines for a fortnight.

In 1782, following the British defeat at Yorktown, a Spanish fleet appeared off the coast of Nassau, and the city surrendered without a fight. Spain returned possession of the Bahamas to Britain the following year, under the terms of the Treaty of Paris.

After American independence, some 7,300 Loyalists and their slaves moved to the Bahamas from New York, Florida, and the Carolinas. These Loyalists established plantations on several islands and became a political force in the capital. The small population became mostly African from this point on.

The British abolished the slave trade in 1807, which led to the forced settlement on Bahamian islands of thousands of Africans liberated from slave ships by the Royal Navy. Slavery itself was finally abolished in the British Empire on August 1, 1834.

20th century

The Duke of Windsor was installed as Governor of the Bahamas, arriving at that post in August 1940 with his new Duchess. They were appalled at the condition of Government House, but they "tried to make the best of a bad situation."[14] He did not enjoy the position, and referred to the islands as "a third-class British colony".[15]

He opened the small local parliament on October 29, 1940, and they visited the 'Out Islands' that November, on Axel Wenner-Gren's yacht, which caused some controversy.[16] The British Foreign Office strenuously objected when the Duke and Duchess planned to tour aboard a yacht belonging to a Swedish magnate, Axel Wenner-Gren, whom American intelligence wrongly believed to be a close friend of Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring.[16][17]

The Duke was praised, however, for his efforts to combat poverty on the islands, although he was as contemptuous of the Bahamians as he was of most non-white peoples of the Empire.[18] He was also praised for his resolution of civil unrest over low wages in Nassau in June 1942, when there was a "full-scale riot,"[19] even though he blamed the trouble on "mischief makers – communists" and "men of Central European Jewish descent, who had secured jobs as a pretext for obtaining a deferment of draft".[20]

The Duke resigned the post on 18 March 1945.[21][22]

Post-World War II

Modern political development began after the Second World War. The first political parties were formed in the 1950s and the British made the islands internally self-governing in 1964, with Sir Roland Symonette, of the United Bahamian Party, as the first Premier.

The fourth James Bond film, Thunderball, was partly filmed in 1965 in Nassau, and The Beatles' film Help! was filmed in part on New Providence Island and Paradise Island the same year.

In 1967, Lynden Pindling (Sir Lynden from 1983), of the Progressive Liberal Party, became the first black Premier of the colony, and in 1968 the title was changed to Prime Minister. In 1973, the Bahamas became fully independent as a Commonwealth realm, thus retaining membership of the Commonwealth of Nations. Sir Milo Butler was appointed the first Governor-General of the Bahamas (the official representative of Queen Elizabeth II) shortly after independence.

Based on the twin pillars of tourism and offshore finance, the Bahamian economy has prospered since the 1950s. However, there remain significant challenges in areas such as education, health care, housing, international narcotics trafficking and illegal immigration from Haiti.

The College of the Bahamas is the national higher education/tertiary system. Offering baccalaureate, masters and associate degrees, COB has three campuses and teaching and research centres throughout the Bahamas. The College is in the process of becoming the University of the Bahamas as early as 2012.

Geography and climate

The country lies between latitudes 20° and 28°N, and longitudes 72° and 80°W.

In 1864, the Governor of the Bahamas reported that there were 29 islands, 661 cays, and 2,387 rocks in the colony.[23]

The closest island to the United States is Bimini, which is also known as the gateway to the Bahamas. The island of Abaco is to the east of Grand Bahama. The southeasternmost island is Inagua. The largest island is Andros Island. Other inhabited islands include Eleuthera, Cat Island, Long Island, San Salvador Island, Acklins, Crooked Island, Exuma and Mayaguana. Nassau, capital city of the Bahamas, lies on the island of New Providence.

All the islands are low and flat, with ridges that usually rise no more than 15 to 20 m (49 to 66 ft). The highest point in the country is Mount Alvernia (formerly Como Hill) on Cat Island. It has an altitude of 63 metres (207 ft).

To the southeast, the Turks and Caicos Islands, and three more extensive submarine features called Mouchoir Bank, Silver Bank, and Navidad Bank, are geographically a continuation of the Bahamas, but not part of the Commonwealth of the Bahamas.[citation needed]

Climate

The climate of the Bahamas is subtropical to tropical, and is moderated significantly by the waters of the Gulf Stream, particularly in winter. Conversely, this often proves very dangerous in the summer and autumn, when hurricanes pass near or through the islands. Hurricane Andrew hit the northern islands during the 1992 Atlantic hurricane season, Hurricane Floyd hit most of the islands in 1999 and Hurricane Irene traversed the entire length of the archipelago as a major hurricane in 2011.

While there has never been a freeze reported in the Bahamas, the temperature can fall as low as 2–3 °C (35.6–37.4 °F) during Arctic outbreaks that affect nearby Florida. Snow was reported to have mixed with rain in Freeport in January 1977, the same time that it snowed in the Miami area.[24] The temperature was about 4.5 °C (40.1 °F) at the time.[25]

| Climate data for Nassau, Bahamas | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 25.4 (77.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.6 (88.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.3 (63.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39.4 (1.55) |

49.5 (1.95) |

54.4 (2.14) |

69.3 (2.73) |

105.9 (4.17) |

218.2 (8.59) |

160.8 (6.33) |

235.7 (9.28) |

164.1 (6.46) |

161.8 (6.37) |

80.5 (3.17) |

49.8 (1.96) |

1,389.4 (54.70) |

| Average precipitation days | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 140 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 220.1 | 220.4 | 257.3 | 276.0 | 269.7 | 231.0 | 272.8 | 266.6 | 213.0 | 223.2 | 222.0 | 213.9 | 2,886 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[26] Hong Kong Observatory[27] for data of sunshine hours | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Okt | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 73 °F

23 °C |

73 °F

23 °C |

75 °F

24 °C |

79 °F

26 °C |

81 °F

27 °C |

82 °F

28 °C |

82 °F

28 °C |

82 °F

28 °C |

82 °F

28 °C |

81 °F

27 °C |

79 °F

26 °C |

75 °F

24 °C |

Government and politics

The Bahamas is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy headed by Queen Elizabeth II in her role as Queen of the Bahamas. Political and legal traditions closely follow those of the United Kingdom and the Westminster system. The two main parties are the Free National Movement and the Progressive Liberal Party.

Tourism generates about half of all jobs, but the number of visitors has dropped significantly since the beginning of the global economic downturn during the last quarter of 2008. Banking and international financial services also have contracted.

The Bahamas is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations as a Commonwealth realm, with Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II as head of state (represented by a Governor-General).

Legislative power is vested in a bicameral parliament, which consists of a 38-member House of Assembly (the lower house), with members elected from single-member districts, and a 16-member Senate, with members appointed by the Governor-General, including nine on the advice of the Prime Minister, four on the advice of the Leader of Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition, and three on the advice of the Prime Minister after consultation with the Leader of the Opposition. The House of Assembly carries out all major legislative functions. As under the Westminster system, the Prime Minister may dissolve Parliament and call a General Election at any time within a five-year term.

The Prime Minister is the head of government and is the leader of the party with the most seats in the House of Assembly. Executive power is exercised by the Cabinet, selected by the Prime Minister and drawn from his supporters in the House of Assembly. The current Governor-General is His Excellency Sir Arthur Foulkes, G.C.M.G., and the current Prime Minister is The Rt. Hon. Perry Christie, P.C., M.P..

The Bahamas has a largely two-party system dominated by the centre-left Progressive Liberal Party and the centre-right Free National Movement. A handful of splinter parties have been unable to win election to parliament. These parties have included the Bahamas Democratic Movement, the Coalition for Democratic Reform, Bahamian Nationalist Party and the Democratic National Alliance.

Constitutional safeguards include freedom of speech, press, worship, movement, and association. Although the Bahamas is not geographically located in the Caribbean, it is a member of the Caribbean Community. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. Jurisprudence is based on English law.

Administrative divisions

The districts of the Bahamas provide a system of local government everywhere except New Providence, whose affairs are handled directly by the central government. In 1996, the Bahamian Parliament passed "The Local Government Act" to facilitate the establishment of Family Island Administrators, Local Government Districts, Local District Councillors, and Local Town Committees for the various island communities. The overall goal of this act is to allow the various elected leaders to govern and oversee the affairs of their respective districts without the interference of Central Government. In total, there are 38 districts, with elections being held every five years. There are also one hundred and ten Councillors and two hundred and eighty-one Town Committee members to correspond with the various districts.[28]

Each Councillor or Town Committee member is responsible for the proper use of public funds for the maintenance and development of their constituency.

The districts other than New Providence are:

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

Military

The Bahamas does not have an army or an air force. Its military is composed of the Royal Bahamas Defence Force (the R.B.D.F.), the navy of The Bahamas. Under The Defence Act, the R.B.D.F. has been mandated, in the name of The Queen, to defend The Bahamas, protect its territorial integrity, patrol its waters, provide assistance and relief in times of disaster, maintain order in conjunction with the law enforcement agencies of The Bahamas, and carry out any such duties as determined by the National Security Council. The Defence Force is also a member of Caricom's Regional Security Task Force.

The R.B.D.F. officially came into existence on March 31, 1980. Their duties include defending The Bahamas, stopping drug smuggling, illegal immigration, poaching, and providing assistance to mariners whenever and wherever they can. The Defence Force has a fleet of 26 coastal and inshore patrol craft along with 6 aircraft and over 1500 personnel including 65 officers and 74 women.

National flag

The colours embodied in the design of the Bahamian flag symbolise the image and aspirations of the people of The Bahamas; the design reflects aspects of the natural environment (sun, sand, and sea) and the economic and social development. The flag is a black equilateral triangle against the mast, superimposed on a horizontal background made up of two colours on three equal stripes of aquamarine, gold and aquamarine.

The symbolism of the flag is as follows: Black, a strong colour, represents the vigour and force of a united people, the triangle pointing towards the body of the flag represents the enterprise and determination of The Bahamian people to develop and possess the rich resources of sun and sea symbolized by gold and aquamarine respectively. In reference to the representation of the people with the colour black, some white Bahamians have joked that they are represented in the thread which "holds it all together."[29]

There are rules on how to use the flag for certain events. For a funeral the National Flag should be draped over the coffin covering the top completely but not covering the bearers. The black triangle on the flag should be placed over the head of the deceased in the coffin. The flag will remain on the coffin throughout the whole service and removed right before lowered into the grave. Upon removal of the flag it should be folded with dignity and put away. The black triangle should never be displayed pointing upwards or from the viewer's right. This would be a sign of distress.[30]

Coat of arms

The Coat of Arms of the Bahamas contains a shield with the national symbols as its focal point. The shield is supported by a marlin and a flamingo, which are the national animals of the Bahamas. The flamingo is located on the land, and the marlin on the sea, indicating the geography of the islands.

On top of the shield is a conch shell, which represents the varied marine life of the island chain. The conch shell rests on a helmet. Below this is the actual shield, the main symbol of which is a ship representing the Santa María of Christopher Columbus, shown sailing beneath the sun. Along the bottom, below the shield appears a banner upon which is scripted the national motto:[31]

"Forward, Upward, Onward Together."

National flower

The yellow elder was chosen as the national flower of the Bahamas because it is native to the Bahama Islands, and it blooms throughout the year.

Selection of the yellow elder over many other flowers was made through the combined popular vote of members of all four of New Providence's garden clubs of the 1970s – the Nassau Garden Club, the Carver Garden Club, the International Garden Club, and the Y.W.C.A. Garden Club.

They reasoned that other flowers grown there – such as the bougainvillea, hibiscus, and poinciana – had already been chosen as the national flowers of other countries. The yellow elder, on the other hand, was unclaimed by other countries (although it is now also the national flower of the United States Virgin Islands).[32]

Economy

One of the most prosperous countries in the West Indies, The Bahamas relies on tourism to generate most of its economic activity. Tourism as an industry not only accounts for over 60 percent of the Bahamian GDP, but provides jobs for more than half the country's workforce.[33] After tourism, the next most important economic sector is financial services, accounting for some 15 percent of GDP.

The government has adopted incentives to encourage foreign financial business, and further banking and finance reforms are in progress. The government plans to merge the regulatory functions of key financial institutions, including the Central Bank of The Bahamas (CBB) and the Securities and Exchange Commission.[citation needed] The Central Bank administers restrictions and controls on capital and money market instruments. The Bahamas International Securities Exchange currently consists of 19 listed public companies. Reflecting the relative soundness of the banking system (mostly populated by Canadian banks), the impact of the global financial crisis on the financial sector has been limited.[citation needed]

The economy has a very competitive tax regime. The government derives its revenue from import tariffs, license fees, property and stamp taxes, but there is no income tax, corporate tax, capital gains tax, value-added tax (VAT), or wealth tax. Payroll taxes fund social insurance benefits and amount to 3.9% paid by the employee and 5.9% paid by the employer.[34] In 2010, overall tax revenue as a percentage of GDP was 17.2%.[35] Authorities are trying to increase tax compliance and collection in the wake of the global crisis. Inflation has been moderate, averaging 3.7 percent between 2006 and 2008.[citation needed]

By the terms of GDP per capita, the Bahamas is one of the richest countries in the Americas.[36]

Ethnic groups

Afro-Bahamians

Afro-Bahamians are Bahamian nationals whose primary ancestry lies in West Africa. The first Africans to arrive to The Bahamas came from Bermuda with the Eleutheran Adventurers as freed slaves looking for a new life. Currently, Afro-Bahamians are the largest ethnic group in The Bahamas, accounting for some 85% of the country's population.[1] The Haitian community numbers about 80,000.[37]

Europeans

According to the 2010 Census of Bahamas, there are a total of 16,598 Whites living there.[38] European Bahamians, or Bahamians of European descent, numbering about 38,000,[39] are mainly the descendants of the English Puritans and American Loyalists who arrived in 1649 and 1783 respectively.[40] They form the largest minority group in The Bahamas, making up some 12% of the population.[1] Many Southern Loyalists went to Abaco, which is about 50% white.[41]

A small portion of the European Bahamian population is descended from Greek labourers who came to help develop the sponging industry in the 1900s. Although making up less than 1% of the nation's population, they have been able to preserve their distinct Greek Bahamian culture.

One of the features of the Bahamian genealogy is that most families have branches, and even immediate family members, spanning the entire spectrum between ‘ light’, 'brown' and ‘unequivocally dark.’[42]

It must be noted that Anglophile former colonies of the United Kingdom, do not use the prefix "Afro" to describe themselves. In all areas, the formal term West Indian is used, despite ancestral origins. The terms Afro and Euro are thrust upon them by the outside world, to categorise the ethnic groups. Attitudes towards race are different in the West Indies, and plays no major role as it would in the United States.

In The Bahamas, the term Bahamian, is the only term in use, as the term West Indian is not readily acknowledged. Also, there is a large number of Bahamians with Shared Decent. A number in which has been inexplicably missing from statistics.

Notable Bahamians of Shared Decent (as according to Bahamian Law)

Demographics

- Population: 354,563

- Age structure: 0–14 years: 25.9% (male 40,085; female 38,959)

- 15–64 years: 67.2% (male 102,154; female 105,482)

- 65 years and over: 6.9% (male 8,772; female 12,704) (2009 est.)

- Population growth rate: 0.925% (2010 est.)[43]

- Birth rate: 17.81 births/1,000 population (2010 est.)

- Death rate: 9.35 deaths/1,000 population (July 2010 est.)

- Net migration rate: -2.13 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2010 est.)

- Infant mortality rate: 23.21 deaths/1,000 live births (2010 est.)

- Life expectancy at birth: total population: 69.87 years.

- Female: 73.49 years (2002 est.)

- Male: 66.32 years

- Total fertility rate: 2.0 children born/woman (2010 est.)[44]

- Nationality: noun: Bahamian(s)

- Adjective: Bahamian /bəˈheɪmiən/

- Ethnic groups: African 85%, European 12%, Asian and Latin Americans 3%.[1]

- Religions: Baptist 35.4%, Anglican 15.1%, Roman Catholic 13.5%, Pentecostal 8.1%, Church of God 4.8%, Methodist 4.2%, other Christian 15.2%,[1] other Protestant 12%, none or unknown 3%, other 2%[45] The 'other' category includes Jews, Muslims, Baha'is, Hindus, Rastafarians, and practitioners of Obeah.[46]

- Languages: English (official), Bahamian Dialect[47]

- Literacy (age 15+): total population: 98.2%

- male: 98.5%

- female: 98% (1995 est.)[48]

Largest cities

Template:Largest cities of The Bahamas

Culture

In the less developed outer islands, handicrafts include basketry made from palm fronds. This material, commonly called "straw", is plaited into hats and bags that are popular tourist items. Another use is for so-called "Voodoo dolls," even though such dolls are the result of the American imagination and not based on historic fact.[49]

A form of folk magic (obeah) is practiced by some Bahamians but, mostly the Haitian-Bahamian community, mainly in the Family Islands (out-islands) of The Bahamas.[50] The practice of obeah is, however, illegal in the Bahamas and punishable by law.[51] Junkanoo is a traditional Bahamian street parade of music, dance, and art held in Nassau (and a few other settlements) every Boxing Day, New Year's Day. Junkanoo is also used to celebrate other holidays and events such as Emancipation Day.

Regattas are important social events in many family island settlements. They usually feature one or more days of sailing by old-fashioned work boats, as well as an onshore festival.

Some settlements have festivals associated with the traditional crop or food of that area, such as the "Pineapple Fest" in Gregory Town, Eleuthera or the "Crab Fest" on Andros. Other significant traditions include story telling.

Bahamians have created a rich literature of poetry, short stories, plays, and short fictional works. Common themes in these works are (1) an awareness of change, (2) a striving for sophistication, (3) a search for identity, (4) nostalgia for the old ways, and (5) an appreciation of beauty. Some contributing writers are Susan Wallace, Percival Miller, Robert Johnson, Raymond Brown, O.M. Smith, William Johnson, Eddie Minnis, Winston Saunders, and many others.[52][53]

See also

- Outline of the Bahamas

- Index of Bahamas-related articles

- Bibliography of the Bahamas

- Template:Wikipedia books link

- List of Bahamians

- List of island countries

- Lucayan Archipelago

- Transport in the Bahamas

- Member of

References

- ^ a b c d e CIA - The World Factbook

- ^ "•GENERAL SITUATION AND TRENDS". Pan American Health Organization.

- ^ "Mission to Long Island in the Bahamas". Evangelical Association of the Caribbean.

- ^ COMPARISON BETWEEN THE 2000 AND 2010 POPULATION CENSUSES AND PERCENTAGE CHANGE.

- ^ a b c d "The Bahamas". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2011" (PDF). United Nations. 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "1973: Bahamas' sun sets on British Empire". BBC News. July 9, 1973. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ^ CIA - The World Factbook

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (7 June 2012). "Ukraine or the Ukraine: Why do some country names have 'the'?". BBC News. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ "Looking for Columbus"[dead link]. Joanne E. Dumene. Five Hundred Magazine. April 1990, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 11–15

- ^ Schools Grapple With Columbus's Legacy: Intrepid Explorer or Ruthless Conqueror?. Education Week. October 9, 1991.

- ^ "Diocesan History". © Copyright 2009 Anglican Communications Department. 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-07.[dead link]

- ^ Woodard, Colin (2010). The Republic of Pirates. Harcourt, Inc. pp. 166–168, 262–314. ISBN 978-0-15-603462-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|authorlink= - ^ Higham, Charles (1988). The Dutchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 300–302.

- ^ Bloch, Michael (1982). The Duke of Windsor's War. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77947-8, p. 364.

- ^ a b Higham, Charles (1988). The Dutchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 307–309.

- ^ Bloch, Michael (1982). The Duke of Windsor's War. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77947-8, pp. 154–159, 230–233

- ^ Ziegler, Philip (1991). King Edward VIII: The official biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-57730-2.

- ^ Higham, Charles (1988). The Dutchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. pp. 331–332.

- ^ Ziegler, pp. 471–472

- ^ Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004; online edition January 2008) "Edward VIII, later Prince Edward, duke of Windsor (1894–1972)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31061, retrieved 1 May 2010 (Subscription required)

- ^ Higham places the date of his resignation as 15 March, and that he left on 5 April. Higham, Charles (1988). The Dutchess of Windsor: The Secret Life. McGraw Hill. p. 359.

- ^ Albury:6

- ^ The Weather Doctor

- ^ Walker, N.D., Roberts, H.H., Rouse, L.J. and Huh, O.K. (1981, November 5). Thermal History of Reef-Associated Environments During A Record Cold-Air Outbreak Event. Coral Reefs (1982) 1:83–87[dead link]

- ^ "Weather Information for Nassau".

- ^ "Climatological Information for Nassau, Bahamas" (1961–1990) – Hong Kong Observatory

- ^ Family Island District Councillors & Town Committee Members

- ^ ASJ-Bahamas Symbol - Flag

- ^ Strachan, Cheryl C. (2010). Flying the Pride. United States of America: Compusec Printing. p. 74. ISBN 9781609572235.

- ^ ASJ-Bahamas National Coat of Arms

- ^ ASJ-Bahamas Symbol - Flower

- ^ "The Bahamas – Economy". Encyclopedia of the Nations. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "Contributions Table". The National Insurance Board of The Commonwealth of The Bahamas. 2010-05-11. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- ^ "Bahamas, The". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2011-12-22.

- ^ GDP (current US$) | Data | Table

- ^ Nick Davis (2009-09-20), Bahamas outlook clouds for Haitians. BBC.

- ^ http://statistics.bahamas.gov.bs/download/095261300.pdf

- ^ David Levinson (1998). "Ethnic groups worldwide: a ready reference handbook". Greenwood Publishing Group. p.317. ISBN 1-57356-019-7

- ^ "The Names of Loyalist Settlers and Grants of Land Which They Received from the Bahamian Government: 1778 - 1783".

- ^ Rachel J. Christmas, Walter Christmas (1984). "Fielding's Bermuda and the Bahamas 1985". Fielding Travel Books. p.158. ISBN 0-688-03965-0

- ^ "A-Z of Bahamas Heritage". Isbndb.com. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ CIA World Factbook

- ^ CIA World Factbook

- ^ Religion, Faith and God in The Bahamas[dead link] – accessed 8 August 2008

- ^ Bahamas – International Religious Freedom Report 2005 – accessed 8 August 2008

- ^ Bahamas Languages – accessed August 8, 2008

- ^ The Bahamas guide

- ^ Hurbon, Laennec. "American Fantasy and Haitian Vodou.” Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Ed. Donald J. Cosentino. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995. 181–97.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2005 - Bahamas". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Dean W. Collinwood and Steve Dodge, "Modern Bahamian Society," Caribbean Books, 1989.

- ^ Dean Collinwood and Rick Phillips, "The National Literature of the New Bahamas," Weber Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Spring) 1990: 43-62.

Further reading

General history

- Cash Philip et al. (Don Maples, Alison Packer). The Making of The Bahamas: A History for Schools. London: Collins, 1978.

- Albury, Paul. The Story of The Bahamas. London: MacMillan Caribbean, 1975.

- Miller, Hubert W. The Colonization of The Bahamas, 1647–1670, The William and Mary Quarterly 2 no.1 (January 1945): 33–46.

- Craton, Michael. A History of The Bahamas. London: Collins, 1962.

- Craton, Michael and Saunders, Gail. Islanders in the Stream: A History of the Bahamian People. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992

- Collinwood, Dean. "Columbus and the Discovery of Self," Weber Studies, Vol. 9 No. 3 (Fall) 1992: 29-44.

- Dodge, Steve. Abaco: The History of an Out Island and its Cays, Tropic Isle Publications, 1983.

- Dodge, Steve. The Compleat Guide to Nassau, White Sound Press, 1987.

Economic history

- Johnson, Howard. The Bahamas in Slavery and Freedom. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishing, 1991.

- Johnson, Howard. The Bahamas from Slavery to Servitude, 1783–1933. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1996.

- Alan A. Block. Masters of Paradise, New Brunswick and London, Transaction Publishers, 1998.

- Storr, Virgil H. Enterprising Slaves and Master Pirates: Understanding Economic Life in the Bahamas. New York: Peter Lang, 2004.

Social history

- Johnson, Wittington B. Race Relations in the Bahamas, 1784–1834: The Nonviolent Transformation from a Slave to a Free Society. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas, 2000.

- Shirley, Paul. "Tek Force Wid Force", History Today 54, no. 41 (April 2004): 30–35.

- Saunders, Gail. The Social Life in the Bahamas 1880s–1920s. Nassau: Media Publishing, 1996.

- Saunders, Gail. Bahamas Society After Emancipation. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishing, 1990.

- Curry, Jimmy. Filthy Rich Gangster/First Bahamian Movie. Movie Mogul Pictures: 1996.

- Curry, Jimmy. To The Rescue/First Bahamian Rap/Hip Hop Song. Royal Crown Records, 1985.

- Collinwood, Dean. The Bahamas Between Worlds, White Sound Press, 1989.

- Collinwood, Dean, and Steve Dodge. Modern Bahamian Society, Caribbean Books, 1989.

- Dodge, Steve, Robert McIntire, and Dean Collinwood. The Bahamas Index, White Sound Press, 1989.

- Collinwood, Dean. "The Bahamas," revised chapter in The Whole World Handbook 1992-1995, 12th ed., New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994.

- Collinwood, Dean. "The Bahamas," chapter in The Whole World Handbook 1992-1993, 11th ed., St. Martin's Press, 1992.

- Collinwood, Dean. "The Bahamas," chapters in Jack W. Hopkins, ed., Latin American and Caribbean Contemporary Record, Vols. 1,2,3,4, Holmes and Meier Publishers, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986.

- Collinwood, Dean. "Problems of Research and Training in Small Islands with a Social Science Faculty," chapter in Social Science in Latin America and the Caribbean, UNESCO, No. 48, 1982.

- Collinwood, Dean, and Rick Phillips, "The National Literature of the New Bahamas," Weber Studies, Vol.7, No. 1 (Spring) 1990: 43-62.

- Collinwood, Dean. "Writers, Social Scientists, and Sexual Norms in the Caribbean," Tsuda Review, No. 31 (November) 1986: 45-57.

- Collinwood, Dean. "Terra Incognita: Research on the Modern Bahamian Society," Journal of Caribbean Studies,Vol. 1, Nos. 2-3 (Winter) 1981: 284-297.

- Collinwood, Dean, and Steve Dodge. "Political Leadership in the Bahamas," The Bahamas Research Institute, No.1, May 1987.

Bibliography

- Boultbee, Paul G. The Bahamas. Oxford: ABC-Clio Press, 1990.

External links

- Official website

Wikimedia Atlas of Bahamas

Wikimedia Atlas of Bahamas- "Bahamas". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- The Bahamas from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Template:Dmoz

- The Bahamas from the BBC News

- Key Development Forecasts for The Bahamas from International Futures

- Maps of the Bahamas from the American Geographical Society Library

- The Bahamas

- Caribbean countries

- Island countries

- Archipelagoes of the Atlantic Ocean

- Former English colonies

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Member states of the Caribbean Community

- Populated places established in 1647

- English-speaking countries and territories

- Constitutional monarchies

- Liberal democracies

- States and territories established in 1973

- Member states of the United Nations