Henry Miller: Difference between revisions

→Brooklyn, 1917-30: Work at Western Union info, references, syntax |

m →Career |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

In 1924 Miller quit Western Union and decided to dedicate himself to writing completely.<ref>http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4597/the-art-of-fiction-no-28-henry-miller</ref> |

In 1924 Miller quit Western Union and decided to dedicate himself to writing completely.<ref>http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4597/the-art-of-fiction-no-28-henry-miller</ref> |

||

Miller's second novel, ''[[Moloch: or, This Gentile World]]'', was written in 1927-28, initially under the guise of a novel written by his wife, [[June Miller|June]].<ref name="pw">[http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-8021-1419-8 “Moloch, Or, This Gentile World,”] ''[[Publisher’s Weekly]]'', September 28, 1992.</ref> A rich older admirer of June, Roland Freedman, paid her to write the novel; she would show him pages of Miller's work each week, pretending it was hers.<ref name="mdearborn">Mary V. Dearborn, “Introduction,” ''Moloch: or, This Gentile World'', New York: [[Grove Press]], 1992, pp. vii-xv.</ref> The book went unpublished until 1992, 65 years after it was written and 12 years after Miller’s death.<ref name="pw" /> ''Moloch'' is based on Miller’s first marriage, to Beatrice, and his years working as a personnel manager at the Western Union office in [[Lower Manhattan]].<ref name="rferguson1">Robert Ferguson, ''Henry Miller: A Life'', pp. 156-58.</ref> A third novel written around this time, ''Crazy Cock'', also went unpublished until after Miller's death. |

Miller's second novel, ''[[Moloch: or, This Gentile World]]'', was written in 1927-28, initially under the guise of a novel written by his second wife, [[June Miller|June]].<ref name="pw">[http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-8021-1419-8 “Moloch, Or, This Gentile World,”] ''[[Publisher’s Weekly]]'', September 28, 1992.</ref> A rich older admirer of June, Roland Freedman, paid her to write the novel; she would show him pages of Miller's work each week, pretending it was hers.<ref name="mdearborn">Mary V. Dearborn, “Introduction,” ''Moloch: or, This Gentile World'', New York: [[Grove Press]], 1992, pp. vii-xv.</ref> The book went unpublished until 1992, 65 years after it was written and 12 years after Miller’s death.<ref name="pw" /> ''Moloch'' is based on Miller’s first marriage, to Beatrice, and his years working as a personnel manager at the Western Union office in [[Lower Manhattan]].<ref name="rferguson1">Robert Ferguson, ''Henry Miller: A Life'', pp. 156-58.</ref> A third novel written around this time, ''Crazy Cock'', also went unpublished until after Miller's death. |

||

===Paris, 1930-39=== |

===Paris, 1930-39=== |

||

Revision as of 19:27, 25 August 2013

Henry Miller | |

|---|---|

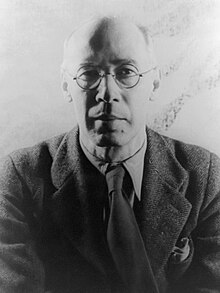

Miller in 1940 | |

| Born | Henry Valentine Miller December 26, 1891 Yorkville, Manhattan, New York City |

| Died | June 7, 1980 (aged 88) Pacific Palisades, California, United States |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Genre | Surrealism, novel |

| Spouse | Beatrice Sylvas Wickens (1917–24) June Miller (1924–34) Janina Martha Lepska (1944–52) Eve McClure (1953–60) Hiroko Tokuda (1967–77) |

| Signature | |

Henry Valentine Miller (December 26, 1891 – June 7, 1980) was an American writer. He was known for breaking with existing literary forms, developing a new sort of semi-autobiographical novel that blended character study, social criticism, philosophical reflection, surrealist free association and mysticism, always distinctly about and expressive of the real-life Henry Miller and yet also fictional.[6] His most characteristic works of this kind are Tropic of Cancer (1934), Black Spring (1936), Tropic of Capricorn (1939) and The Rosy Crucifixion trilogy (1949-59), all of which were banned in the United States until 1961.[7] He also wrote travel memoirs and literary criticism, and painted watercolors.[8]

Early life

Miller was born to German parents, tailor Heinrich Miller and Louise Marie Neiting, in the Yorkville section of Manhattan, New York City.[9] As a child, he lived for nine years at 662 Driggs Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn,[10] known in that time (and referred to frequently in his works) as the Fourteenth Ward. As a young man, he was active with the Socialist Party of America (his "quondam idol" was the Black Socialist Hubert Harrison).[11] He attended the City College of New York for one semester.

Career

Brooklyn, 1917-30

Miller married his first wife, Beatrice Sylvas Wickens, in 1917; they divorced in 1924.[12] Together they had a daughter, Barbara, born in 1919.[13] Miler later describes this time - his struggles to become a writer, his sexual escapades, failures, friends and philosophy in his autobiographical trilogy The Rosy Crucifixion.

Miller was working at the Western Union at the time. In March 1922, during a three week vacation, he wrote his first novel, Clipped Wings. It has never been published, and only fragments remain, although parts of it were recycled in other works, such as Tropic of Capricorn.[14] A study of twelve Western Union messengers, Miller called Clipped Wings "a long book and probably a very bad one."[15]

In 1924 Miller quit Western Union and decided to dedicate himself to writing completely.[16]

Miller's second novel, Moloch: or, This Gentile World, was written in 1927-28, initially under the guise of a novel written by his second wife, June.[17] A rich older admirer of June, Roland Freedman, paid her to write the novel; she would show him pages of Miller's work each week, pretending it was hers.[18] The book went unpublished until 1992, 65 years after it was written and 12 years after Miller’s death.[17] Moloch is based on Miller’s first marriage, to Beatrice, and his years working as a personnel manager at the Western Union office in Lower Manhattan.[19] A third novel written around this time, Crazy Cock, also went unpublished until after Miller's death.

Paris, 1930-39

In 1928, Miller spent several months in Paris with June, a trip which was financed by Freedman.[19] In 1930, Miller moved to Paris unaccompanied, and he continued to live there on the rue Bonaparte until the outbreak of World War II.[20] Although Miller had little or no money the first year in Paris, things began to change with the meeting of Anaïs Nin who, with Hugh Guiler, went on to pay his entire way through the 1930s including the rent for an apartment at 18 Villa Seurat. Anaïs Nin became his lover and financed the first printing of Tropic of Cancer in 1934 with money from Otto Rank.[21]

In late 1931, Miller was employed by the Chicago Tribune Paris edition, thanks to his friend Alfred Perlès who worked there, as a proofreader. Miller took this opportunity to submit some of his own articles under Perlès name, since at that time (1934) only the editorial staff were permitted to publish in the paper. This period in Paris was highly creative for Miller, and during this time he also established a significant and influential network of authors circulating around the Villa Seurat.[22] At that time a young British author, Lawrence Durrell, became a lifelong friend. Miller's correspondence with Durrell was later published in two books.[23][24] During his Paris period he was also influenced by the French Surrealists.

His works contain detailed accounts of sexual experiences. His first published book, Tropic of Cancer (1934), was banned in the United States on the grounds of obscenity.[25] He continued to write novels that were banned; along with Tropic of Cancer, his Black Spring (1936) and Tropic of Capricorn (1939) were smuggled into his native country, building Miller an underground reputation.

Miller lived in France until June 1939.[26]

Greece, 1939-40

In 1939 Durrell, who lived in Corfu, invited Miller to Greece. Miller described the visit in The Colossus of Maroussi (1941), which he considered his best book.[27] One of the first acknowledgments of Henry Miller as a major modern writer was by George Orwell in his 1940 essay "Inside the Whale", where he wrote:

Here in my opinion is the only imaginative prose-writer of the slightest value who has appeared among the English-speaking races for some years past. Even if that is objected to as an overstatement, it will probably be admitted that Miller is a writer out of the ordinary, worth more than a single glance; and after all, he is a completely negative, unconstructive, amoral writer, a mere Jonah, a passive acceptor of evil, a sort of Whitman among the corpses.[28]

California, 1942-80

In 1940, Miller returned to New York; after a year-long trip around the United States, a journey that would become material for The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, he moved to California in June 1942, initially residing just outside Hollywood in Beverly Glen, before settling in Big Sur in 1944.[26] In February 1963, Miller moved to 444 Ocampo Drive, Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, California, where he would spend the last 18 years of his life.[29]

While Miller was establishing his base in Big Sur, the Tropic books, still banned in the USA, were being published in France by the Obelisk Press and later the Olympia Press. There they were acquiring a slow and steady notoriety among both Europeans and the various enclaves of American cultural exiles. As a result, the books were frequently smuggled into the States, where they proved to be a major influence on the new Beat generation of American writers (most notably Jack Kerouac) some of whom adopted stylistic and thematic principles found in Miller's oeuvre.

In 1942, shortly before moving to California, Miller began writing Sexus, the first novel in The Rosy Crucifixion trilogy, a fictionalized account documenting the six-year period of his life in Brooklyn falling in love with June and struggling to become a writer.[30] Like several of his other works, the trilogy, completed in 1959, was initially banned in the United States, published only in France and Japan.[31] In other works written during his time in California, Miller was widely critical of consumerism in America, as reflected in Sunday After The War (1944) and The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (1945).

In 1967, Miller married his fifth wife, Hoki Tokuda.[32][33]

In 1968, Miller signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[34]

After his move to Ocampo Drive, he held dinner parties for the artistic and literary figures of the time. His cook and caretaker was a young artist's model named Twinka Thiebaud who later wrote a 1981 book of his evening chats.[35] Thiebaud's memories of Miller's table talk were published in a rewritten and retitled book in 2011.[36]

During the last four years of his life, Miller held an ongoing correspondence of over 1,500 letters with Brenda Venus, a young Playboy playmate, actress and dancer. A book about their correspondence was published in 1986.[37]

Late in life, Miller filmed with Warren Beatty for his film Reds. He spoke of his remembrances of John Reed and Louise Bryant as part of a series of "witnesses." The film was released eighteen months after Miller's death.[38]

Death

Miller died of circulatory complications at his home in Pacific Palisades on June 7, 1980, at the age of 88.[39] His body was cremated and his ashes shared between his son Tony and daughter Val. Tony has stated that he ultimately intends to have his own ashes mixed with his father's and scattered in Big Sur.[40]

US publication of previously banned works

The publication of Miller's Tropic of Cancer in the United States in 1961 by Grove Press led to a series of obscenity trials that tested American laws on pornography. The U.S. Supreme Court, in Grove Press, Inc., v. Gerstein, citing Jacobellis v. Ohio (which was decided the same day in 1964), overruled the state court findings of obscenity and declared the book a work of literature; it was one of the notable events in what has come to be known as the sexual revolution. Elmer Gertz, the lawyer who successfully argued the initial case for the novel's publication in Illinois, became a lifelong friend of Miller's; a volume of their correspondence has been published.[41] Following the trial, in 1964-65, other books of Miller's which had also been banned in the US were published by Grove Press: Black Spring, Tropic of Capricorn, Quiet Days in Clichy, Sexus, Plexus and Nexus.[42]

Watercolors

In addition to his literary abilities, Miller produced numerous watercolor paintings and wrote books on this field. He was a close friend of the French painter Grégoire Michonze. It is estimated that Miller painted 2,000 watercolors during his life, and that 50 or more major collections of Miller’s paintings exist.[43] The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin holds a selection of Miller's watercolors,[44] as did the Henry Miller Museum of Art in Ōmachi City in Nagano, Japan, before closing in 2001.[45] Miller's daughter Valentine placed some of her father's art for sale in 2005.[46] He was also an amateur pianist.[citation needed]

Legacy

Miller is considered a "literary innovator" in whose works "actual and imagined experiences became indistinguishable from each other."[47] His books did much to free the discussion of sexual subjects in American writing from both legal and social restrictions.

Miller's papers can be found in the following library special collections:

- Southern Illinois University Carbondale, which has correspondence and other archival collections.[48]

- Syracuse University, which holds a portion of the correspondence between the Grove Press and Henry Miller.[49]

- Charles E. Young Research Library of the University of California, Los Angeles Library.[50]

- Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, which has materials about Miller from his first wife and their daughter.[51]

- University of Victoria, which holds a significant collection of Miller's manuscripts and correspondence, including the corrected typescripts for Max and Quiet Days in Clichy, as well as Miller's lengthy correspondence with Alfred Perlès.[52]

- University of Virginia.[53]

- Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University Library.[54]

Miller's friend Emil White founded the nonprofit Henry Miller Memorial Library in Big Sur in 1981.[55] This houses a collection of his works and celebrates his literary, artistic and cultural legacy by providing a public gallery as well as performance and workshop spaces for artists, musicians, students, and writers.[55]

Selected works

- Moloch: or, This Gentile World, written in 1927, published posthumously by the Estate of Henry Miller. New York: Grove Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8021-3372-X

- Crazy Cock, written 1928–1930, published posthumously by the Estate of Henry Miller. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991. ISBN 0-8021-1412-1

- Tropic of Cancer, Paris: Obelisk Press, 1934.

- New York: Grove Press, 1961. ISBN 0-8021-3178-6

- What Are You Going to Do about Alf? An Open Letter to All and Sundry, Paris: Printed at author's expense, 1935.

- London: Turret, 1971. ISBN 0-85469-022-0

- Aller Retour New York, Paris: Obelisk Press, 1935.

- New York: New Directions, 1991. ISBN 0-8112-1193-2

- Black Spring, Paris: Obelisk Press, 1936.

- New York: Grove Press, 1963. ISBN 0-8021-3182-4

- Max and the White Phagocytes, Paris: Obelisk Press, 1938.

- Tropic of Capricorn, Paris: Obelisk Press, 1939.

- New York: Grove Press, 1961. ISBN 0-8021-5182-5

- Hamlet Volume I with Michael Fraenkel, New York: Carrefour, 1939.

- Hamlet Volume II with Michael Fraenkel, New York: Carrefour, 1941.

- Above two volumes republished, minus two letters, as Henry Miller's Hamlet Letters, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1988. ISBN 0-88496-269-5

- The Cosmological Eye, Norfolk, CT: New Directions, 1939. ISBN 0-8112-0110-4

- The World of Sex, Chicago: Ben Abramson, Argus Book Shop, 1940.

- Richmond, England: Oneworld Classics, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84749-035-3

- Under the Roofs of Paris, written as Opus Pistorum in 1941, published posthumously by the Estate of Henry Miller. New York: Grove Press, 1983. ISBN 0-8021-3183-2

- The Colossus of Maroussi, San Francisco: Colt Press, 1941.

- New York: New Directions, 1958. ISBN 0-8112-0109-0

- The Wisdom of the Heart, Norfolk, CT: New Directions, 1941.

- New York: New Directions, 1960. ISBN 0-8112-0116-3

- Sunday after the War, Norfolk, CT: New Directions, 1944.

- Semblance of a Devoted Past, Berkeley, CA: Bern Porter, 1944.

- The Plight of the Creative Artist in the United States of America, Houlton, ME: Bern Porter, 1944.

- Echolalia, Berkeley, CA: Bern Porter, 1945.

- Henry Miller Miscellanea, San Mateo, CA: Bern Porter, 1945.

- Why Abstract?, with Hilaire Hiler and William Saroyan, New York: New Directions, 1945.

- New York: Haskell House, 1974. ISBN 0-8383-1837-1

- The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, New York: New Directions, 1945.

- New York: New Directions, 1970. ISBN 0-8112-0106-6

- Maurizius Forever, San Francisco: Colt Press, 1946.

- Remember to Remember, New York: New Directions, 1947. (Volume 2 of The Air-Conditioned Nightmare.)

- London: Grey Walls Press, 1952.

- Into the Night Life, privately published 1947 with Bezalel Schatz

- The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1948.

- Kansas City, MO: Hallmark Editions, 1971. ISBN 0-87529-173-2

- Sexus (Book One of The Rosy Crucifixion), Paris: Obelisk Press, 1949.

- New York: Grove Press, 1987. ISBN 0-394-62371-1

- The Waters Reglitterized: The Subject of Water Color in Some of Its More Liquid Phases, San Jose, CA: John Kidis, 1950.

- Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1973. ISBN 0-912264-71-3

- The Books in My Life, Norfolk, CT: New Directions, 1952.

- New York: New Directions, 1969. ISBN 0-8112-0108-2

- Plexus (Book Two of The Rosy Crucifixion), Paris: Olympia Press, 1953.

- New York: Grove Press, 1963. ISBN 0-8021-5179-5

- Quiet Days in Clichy With Photographs by Brassaï, Paris: Olympia Press, 1956.

- New York: Grove Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8021-3016-X

- Richmond, England: Oneworld Classics, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84749-036-0

- Henry Miller Recalls and Reflects: An Extraordinary American Writer Speaks Out (2 LP records, RLP 7002/3), New York: Riverside Records, 1956.

- The Time of the Assassins: A Study of Rimbaud, New York: New Directions, 1956.

- New York: New Directions, 1962. ISBN 0-8112-0115-5

- A Devil in Paradise, New York: New American Library, 1956.

- New York: New Directions, 1993. ISBN 0-8112-1244-0

- Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch, New York: New Directions, 1957. ISBN 0-8112-0107-4

- The Red Notebook, Highlands, NC: Jonathan Williams, 1958.

- Reunion in Barcelona: a Letter to Alfred Perlès, from Aller Retour New York, Northwood, England: Scorpion Press, 1959.

- Nexus (Book Three of The Rosy Crucifixion), Paris: Obelisk Press, 1960.

- New York: Grove Press, 1965. ISBN 0-8021-5178-7

- To Paint Is to Love Again, Alhambra, CA: Cambria Books, 1960.

- New York: Grossman Publishers, 1968.

- Paris 1928 (Nexus II), abandoned continuation of Nexus, 1961.

- Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

- Watercolors, Drawings, and His Essay "The Angel Is My Watermark," New York: Abrams, 1962.

- Stand Still Like the Hummingbird, New York: New Directions, 1962. ISBN 0-8112-0322-0

- Just Wild about Harry, New York: New Directions, 1963.

- New York: New Directions, 1979. ISBN 0-8112-0724-2

- Greece (with drawings by Anne Poor), New York: Viking Press, 1964.

- Henry Miller on Writing, New York: New Directions, 1964. ISBN 0-8112-0112-0

- Insomnia or the Devil at Large, Albuquerque: Loujon Press, 1970.

- Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974.

- First Impressions of Greece, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1973. ISBN 0-912264-59-4

- Reflections on The Maurizius Case: A Humble Appraisal of a Great Book, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1974. ISBN 0-912264-73-X

- Henry Miller's Book of Friends: A Tribute to Friends of Long Ago, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1976. ISBN 0-88496-050-1

- Sextet, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1977. ISBN 0-88496-119-2

- New York: New Directions, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8112-1800-9

- My Bike and Other Friends, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1978. ISBN 0-88496-075-7

- Joey: a Loving Portrait of Alfred Perlès Together With Some Bizarre Episodes Relating to the Opposite Sex, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1979. ISBN 0-88496-136-2

Films

Miller as himself

Miller appeared as himself in several films:[56]

- He was the subject of four documentary films by Robert Snyder; The Henry Miller Odyssey (90 minutes), Henry Miller: Reflections On Writing (47 minutes), and Henry Miller Reads and Muses (60 minutes). In addition, there is a film by Snyder that was completed after Snyder's death in 2004 about Miller's watercolor paintings, Henry Miller: To Paint Is To Love Again (60 mimutes). All four films are in Miller's own words.

- He was a "witness" (interviewee) in Warren Beatty's 1981 film Reds.[57]

- He was featured in the 1996 documentary Henry Miller Is Not Dead that featured music by Laurie Anderson.[58]

Actors portraying Miller

Several actors played Miller on film, such as:

- Rip Torn in the 1970 film adaptation of Tropic of Cancer.

- In the 1970 Jens Jørgen Thorsen adaptation of Quiet Days in Clichy, the Miller-based character of 'Joey' was played by Paul Valjean.

- Fred Ward in the 1990 film Henry & June, based on the diaries of Anaïs Nin.

- David Brandon in the 1990 film The Room of Words (La stanza delle parole), also based on the diaries of Anaïs Nin.

- Claude Chabrol's 1990 adaptation of Quiet Days in Clichy saw Andrew McCarthy play Miller.

References

- ^ a b c d "Henry Miller: the 100 Books that influenced me most"

- ^ Hemmingson, Michael (October 9, 2008). The Dirty Realism Duo: Charles Bukowski & Raymond Carver. Borgo Press. pp. 70, 71. ISBN 1-4344-0257-6.

- ^ http://www.lifepositive.com/spirit/traditional-paths/sorcery/coelho.asp

- ^ http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/5438/the-art-of-fiction-no-184-barry-hannah

- ^ http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/619/the-art-of-journalism-no-1-hunter-s-thompson

- ^ Shifreen, Lawrence J. (1979). Henry Miller: a Bibliography of Secondary Sources. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 75–77.

...Miller's metamorphosis and his acceptance of the cosmos.

- ^ http://www.thefileroom.org/documents/dyn/DisplayCase.cfm/id/1275

- ^ http://www.henrymiller.info/gallery/

- ^ McCarthy, Harold T (1971). "Henry Miller's Democratic Vistas". American Quarterly. 23 (2): 221–235. JSTOR 2711926.

...largely German-speaking neighborhood (Miller's grandparents had emigrated from Germany)

- ^ Jake Mooney, "'Ideal Street' Seeks Eternal Life," The New York Times, May 1, 2009.

- ^ Introduction from A Hubert Harrison Reader, University Press of New England

- ^ Frederick Turner, Renegade: Henry Miller and the Making of Tropic of Cancer, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011, pp. 88, 104.

- ^ Robert Ferguson, Henry Miller: A Life, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991, p. 60.

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn, The Happiest Man Alive, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991, pp. 70-71.

- ^ Henry Miller (ed. Antony Fine), Henry Miller: Stories, Essays, Travel Sketches, New York: MJF Books, 1992, p. 5.

- ^ http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4597/the-art-of-fiction-no-28-henry-miller

- ^ a b “Moloch, Or, This Gentile World,” Publisher’s Weekly, September 28, 1992.

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn, “Introduction,” Moloch: or, This Gentile World, New York: Grove Press, 1992, pp. vii-xv.

- ^ a b Robert Ferguson, Henry Miller: A Life, pp. 156-58.

- ^ Anderson, Christiann (March 2004). "Henry Miller: Born to be Wild". BonjourParis. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Ferguson, Robert. Henry Miller: A Life. New York: W.W. Norton, 1991.

- ^ Gifford, James. Ed. The Henry Miller-Herbert Read Letters: 1935–58. Ann Arbor: Roger Jackson Inc., 2007.

- ^ Wickes, George, ed. (1963). Lawrence Durrell & Henry Miller: A Private Correspondence. New York: Dutton. OCLC 188175.

- ^ MacNiven, Ian S, ed. (1988). The Durrell-Miller Letters 1935–80. London: Faber. ISBN 0-571-15036-5.

- ^ Baron, Dennis (October 1, 2009). "Celebrate Banned Books Week: Read Now, Before It's Too Late". Web of Language. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Henry Miller, Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch, New York: New Directions, 1957, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Wickes, George (Summer–Fall 1962). "Henry Miller, The Art of Fiction No. 28". The Paris Review.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Orwell, George "Inside the Whale", London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1940.

- ^ Robert Ferguson, Henry Miller: A Life, p. 351.

- ^ Robert Ferguson, Henry Miller: A Life, p. 295.

- ^ Frank Getlein, "Henry Miller's Crowded Simple Life," Milwaukee Journal, June 9, 1957.

- ^ Carolyn Kellogg, "Henry Miller's last wife, Hoki Tokuda, remembers him, um, fondly?", Los Angeles Times, February 23, 2011.

- ^ John M. Glionna, "A story only Henry Miller could love", Los Angeles Times, February 22, 2011.

- ^ “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest,” New York Post, January 30, 1968.

- ^ Thiebaud, Twinka. Reflections: Henry Miller. Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1981. ISBN 0-88496-166-4

- ^ Thiebaud, Twinka. What Doncha Know? about Henry Miller. Belvedere, CA: Eio Books, 2011. ISBN 978-0-9759255-2-2

- ^ Dear, Dear Brenda: The Love Letters of Henry Miller to Brenda Venus. New York: Morrow, 1986. ISBN 0-688-02816-0

- ^ Vincent Canby, "Beatty's 'Reds,' With Diane Keaton," New York Times, December 4, 1981.

- ^ Alden Whitman, "Henry Miller, 88, Dies in California," New York Times, June 9, 1980.

- ^ "Playing Ping Pong With Henry Miller," BBC Radio 4, July 25, 2013.

- ^ Henry Miller: Years of Trial & Triumph, 1962–1964: The Correspondence of Henry Miller and Elmer Gertz. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. 1978. ISBN 0-8093-0860-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Henry Miller, Preface to Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch, New York: New Directions, 1957, p. ix.

- ^ Coast Publishing. "Henry Miller: The Centennial Print Collection" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ "Henry Miller: An Inventory of His Art Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ "Henry Miller Art Museum to Close". Japan Times. August 31, 2001. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ Miller, Valentine (2005). "Henry Miller: A Personal Collection". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ Sipper, Ralph B. (January 6, 1991). "Miller's Tale: Henry Hits 100". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ Southern Illinois University Special Collections Research Center. "Search Results for "Henry Miller"". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ "Grove Press Records: an inventory of its records at Syracuse University". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ "Finding Aid for the Henry Miller Papers, 1896–1984, 1930–1980". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ "Beatrice Wickens Miller Sandford and Barbara Miller Sandford: A Preliminary Inventory of Their Collection of Henry Miller in the Manuscript Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ University of Victoria Library. "Henry Miller collection". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ University of Virginia Library. "Search results for "Henry Miller"". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ Yale University Library. "Guide to the Henry Miller Papers". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ a b "About the Henry Miller Library". Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ^ Henry Miller at IMDb

- ^ "Reds" by Steinberg, Jay S. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 15, 2013

- ^ "Henry Miller Is Not Dead". Moving Images Distribution Society. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

Further reading

- Durrell, Lawrence, editor. The Henry Miller Reader, New York: New Directions Publishing, 1959. ISBN 0-8112-0111-2

- Widmer, Kingsley. Henry Miller, New York: Twayne, 1963.

- Revised edition, Boston: Twayne, 1990. ISBN 0-8057-7607-9

- Wickes, George, and Harry Thornton Moore. Henry Miller and the Critics, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1963.

- Wickes, George. Henry Miller, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1966.

- Gordon, William A. The Mind and Art of Henry Miller, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967.

- Mailer, Norman. Genius and Lust: a Journey Through the Major Writings of Henry Miller, New York: Grove Press, 1976. ISBN 0-8021-0127-5

- Martin, Jay. Always Merry and Bright: the Life of Henry Miller: an Unauthorized Biography, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1978. ISBN 0-88496-082-X

- Young, Noel, editor. The Paintings of Henry Miller: Paint as You Like and Die Happy, Santa Barbara, CA: Capra Press, 1982. ISBN 0-87701-280-6

- Winslow, Kathryn. Henry Miller: Full of Life, Los Angeles: J. P. Tarcher, 1986. ISBN 0-87477-404-7

- Brown, J. D. Henry Miller, New York: Ungar, 1986. ISBN 0-8044-2077-7

- Stuhlmann, Gunther, editor. A Literate Passion: Letters of Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller, 1932–1953. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987. ISBN 0-15-152729-6

- Dearborn, Mary V. The Happiest Man Alive: A Biography of Henry Miller, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991. ISBN 0-671-67704-7

- Ferguson, Robert. Henry Miller: A Life, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991. ISBN 0-393-02978-6

- Jong, Erica. The Devil at Large: Erica Jong on Henry Miller, New York: Turtle Bay Books, 1993. ISBN 0-394-58498-8

- Fitzpatrick, Elayne Wareing. Doing It With the Cosmos: Henry Miller's Big Sur Struggle for Love Beyond Sex, Philadelphia: Xlibris, 2001. ISBN 1-4010-1048-2

- Brassaï. Henry Miller, Happy Rock, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002. ISBN 0-226-07139-1

- Masuga, Katy. Henry Miller and How He Got That Way, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-7486-4118-5

- Masuga, Katy. The Secret Violence of Henry Miller, Rochester, NY: Camden House Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1-57113-484-4

- Turner, Frederick. Renegade: Henry Miller and the Making of Tropic of Cancer, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-300-14949-4

External links

- Works by Henry Miller at Open Library

- Henry Miller Online by Dr. Hugo Heyrman, a tribute

- Ibarguen, Raoul R. Narrative Detours: Henry Miller and the Rise of New Critical Modernism, excerpts from a 1989 Ph.D. thesis

- Nexus: The International Henry Miller Journal

- Rexroth, Kenneth. "The Reality of Henry Miller" and "Henry Miller: The Iconoclast as Everyman’s Friend" (1955–1962 essays)

- Schiller, Tom, director. Henry Miller Asleep & Awake (1975), a 34-minute video

- Smithsonian Folkways. An Interview with Henry Miller (1964), with link to transcript (in "liner notes")

- Miller documentaries by Robert Snyder at Masters & Masterworks

- UbuWeb Sound: Henry Miller (1891–1980), with links to MP3 files of "An Interview with Henry Miller" (1964), "Life As I See It" (1956/1961), and "Henry Miller Recalls and Reflects" (1957)

- Template:Worldcat id

- Young, Richard, director. Dinner with Henry Miller (1979), a 30-minute video

- 1891 births

- 1980 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- American anarchists

- American erotica writers

- American essayists

- American expatriates in France

- American male novelists

- American memoirists

- American people of German descent

- American tax resisters

- Anarchist writers

- Anarchist artists

- Analysands of Otto Rank

- Writers from New York

- Obscenity controversies