Nanjing: Difference between revisions

m Added a source for the sentence about the romanization of Nanking / Nanjing Tag: gettingstarted edit |

added Category:Cities with millions of inhabitants using HotCat |

||

| Line 883: | Line 883: | ||

[[Category:Yangtze River Delta]] |

[[Category:Yangtze River Delta]] |

||

[[Category:World Digital Library related]] |

[[Category:World Digital Library related]] |

||

[[Category:Cities with millions of inhabitants]] |

|||

{{Link GA|zh}} |

{{Link GA|zh}} |

||

Revision as of 00:08, 16 July 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

Nanjing

南京市 | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: 1. the city, Xuanwu Lake and Purple Mountain; 2. stone sculpture "bixie"; 3. Jiming Temple; 4. Yijiang Gate with the City Wall of Nanjing; 5. Qinhuai River and Fuzi Miao; 6. Nanjing Olympic Sports Centre; 7. the spirit way of Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum; 8. Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum | |

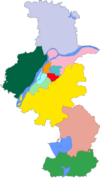

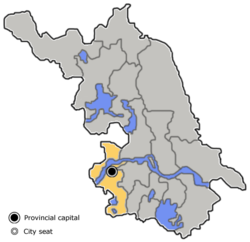

Location of Nanjing City jurisdiction in Jiangsu | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Jiangsu |

| County-level | 11 |

| Township-level | 129 |

| Settled | 495 BC |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sub-provincial city |

| • CPC Ctte Secretary | Yang Weize |

| • Mayor | Miao Ruilin |

| Area | |

| 6,598 km2 (2,548 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 20 m (50 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| 8,161,800 | |

| • Density | 1,237/km2 (3,183/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 8,161,800 |

| Demonym | Nanjinger |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 210000–211300 |

| Area code | 25 |

| GDP (Nominal) | 2013 |

| - Total | US$131.4 billion |

| - Per capita | US$ 16,210 |

| - Growth | |

| GDP (PPP) | 2013 |

| - Total | US$210.7 billion |

| - Per capita | US$ 26,013 |

| Licence plate prefixes | 苏A |

| Website | City of Nanjing |

Deodar Cedar (Cedrus deodara), Platanus × acerifolia[1] Méi (Prunus mume) | |

Template:Contains Chinese text

| Nanjing | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 南京 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Nánjīng | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Nanking | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | southern capital | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Nanjing (ⓘ; Chinese: 南京; pinyin: Nánjīng; Wade–Giles: Nan-ching) is the capital of Jiangsu province in Eastern China.[2] It has a prominent place in Chinese history and culture, having been the capital of China on several occasions historically.[3] Its present name means "Southern Capital" and was widely romanized as Nankin and Nanking until the pinyin language reform, after which Nanjing was gradually adopted as the standard spelling of the city's name in most languages that use the Roman alphabet.[4]

Located in the lower Yangtze River drainage basin and Yangtze River Delta economic zone, Nanjing has long been one of China's most important cities.[5][6][7] Having been the capital city of six different dynasties since 3 A.D., it is recognized as one of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China.[8] It was the capital of Wu during the Three Kingdoms Period,[9] and the capital of the Republic of China prior to its flight to Taiwan during the Chinese Civil War.[10] Nanjing is also one of the fifteen sub-provincial cities in the People's Republic of China's administrative structure,[11] enjoying jurisdictional and economic autonomy only slightly less than that of a province.[12] Nanjing has long been a national centre of education, research, transport networks and tourism. The city will host the 2014 Summer Youth Olympics.[13]

With an total population of 8.16 million[14][15] and a urban population of 6.55 million,[16][17] Nanjing is the second-largest commercial centre in the East China region after Shanghai. It has been ranked seventh in the evaluation of "Cities with Strongest Comprehensive Strength" issued by the National Statistics Bureau, and second in the evaluation of cities with most sustainable development potential in the Yangtze River Delta. It has also been awarded the title of 2008 Habitat Scroll of Honour of China, Special UN Habitat Scroll of Honour Award and National Civilized City.[18]

History

Early history

Nanjing was one of the earliest established cities in what is now China. According to legend,[which?] Fu Chai, Lord of the State of Wu, founded a fort named Yecheng (冶城) in today's Nanjing area in 495 BCE. Later in 473 BCE, the State of Yue conquered Wu and constructed the fort of Yuecheng (越城) on the outskirts of the present-day Zhonghua Gate. In 333 BCE, after eliminating the State of Yue, the State of Chu built Jinling Yi (金陵邑) in the western part of present-day Nanjing. Under the Qin and Han dynasties, it was called Moling (秣陵). Since then, the city had experienced destruction and renewal many times.[citation needed]

Capital of the Six Dynasties

Nanjing first became a capital in 229 CE, where Sun Quan of the Wu Kingdom during the Three Kingdoms Period relocated its capital to Jianye (建業), a city he extended on the basis of Jinling Yi in 211 CE.[9] Although conquered by the West Jin dynasty in 280, Nanjing and its neighbouring areas had been well cultivated and developed into one of the commercial, cultural and political centers of China during the rule of East Wu. This city would soon play a vital role in the following centuries.

Shortly after the unification of the region, the state of West Jin collapsed in wars. It was at first rebellions by eight Jin princes for the throne and later rebellions and invasion from Xiongnu and other nomadic peoples that destroyed the rule of Jin in the north. In 317, remnants of the Jin court, as well as nobles and wealthy families, fled from the north to the south and reestablished the Jin court in Nanjing, which was then called Jiankang (建康).

During the period of North–South division, Nanjing remained the capital of the Southern dynasties for more than two and a half centuries. During this time, Nanjing was the international hub of East Asia and one of the largest cities in the world.[20] Based on historical documents, the city had 280,000 registered households.[21] Assuming an average Nanjing household had about 5.1 people at that time, the city had more than 1.4 million residents.[citation needed]

A number of sculptural ensembles of that era, erected at the tombs of royals and other dignitaries, have survived (in various degrees of preservation) in Nanjing's northeastern and eastern suburbs, primarily in Qixia and Jiangning District.[22] Possibly the best preserved of them is the ensemble of the Tomb of Xiao Xiu (475–518), a brother of Emperor Wu of Liang.[23][24] The period of division ended when the Sui Dynasty reunified China and almost destroyed the entire city, turning it into a small town.

Sui to Yuan dynasty

The city of Nanjing was razed after the Sui took over it. It was reconstructed during the late Tang dynasty.[25] It was chosen as the capital and called Jinling (金陵) during the Southern Tang (937–976), a state that came succeeded the Wu.[26] Jiankang's textile industry burgeoned and thrived during the Song dynasty despite the constant threat of foreign invasions from the north by the Jurchen Jin dynasty. Nanjing was the capital of Da Chu, a puppet state established by the Jurchens.[27] Da Chu came to an end scarcely a month after its creation.[28] The Mongol Empire eventually occupied much of the territory that now constitutes China and further consolidated the city's status as a hub of the textile industry under what became known in China as the Yuan dynasty.[29]

Ming Dynasty—capital

The first emperor of the Ming dynasty Zhu Yuanzhang, the Hongwu Emperor, who overthrew the Yuan dynasty renamed the city Yingtian, rebuilt it, and made it the dynastic capital in 1368. He constructed a 48 km (30 mi) long city wall around Yingtian, as well as a new Ming Palace complex, and government halls.[30] It took 200,000 laborers 21 years to finish the project. The present-day City Wall of Nanjing was mainly built during that time and today it remains in good condition and has been well preserved.[31] It is among the longest surviving city walls in China.[32] the Jianwen Emperor ruled from 1398 to 1402.

It is believed that Nanjing was the largest city in the world from 1358 to 1425 with a population of 487,000 in 1400.[33] Nanjing remained the capital of the Ming Empire until 1421, when the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty, Zhu Di the Yongle Emperor, relocated the capital to Beijing.

Besides the city wall, other famous Ming-era structures in the city included the famous Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum and Porcelain Tower, although the latter was destroyed by the Taipings in the 19th century either in order to prevent a hostile faction from using it to observe and shell the city[34] or from superstitious fear of its geomantic properties.[35]

A monument to the huge human cost of some of the gigantic construction projects of the early Ming is the Yangshan Quarry (located some 10 km (6 mi) east of the walled city an Ming Xiaoling), where a gigantic stele, cut on the orders of the Yongle Emperor, lies abandoned, just as it was left 600 years ago when it was understood it was impossible to move or erect it.[36]

As the center of the empire, early-Ming Nanjing had worldwide connections. It was home of the admiral Zheng He, who went to sail the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and it was visited by foreign dignitaries, such as a king from Borneo (Boni 渤泥), who died during his visit to China in 1408. The Tomb of the King of Boni, with a spirit way and a tortoise stele, was discovered in Yuhuatai District (south of the walled city) in 1958, and has been restored.[37]

Southern Ming Dynasty

Over two centuries after the removal of the capital to Beijing, Nanjing was destined to become the capital of a Ming emperor one more time. After the fall of Beijing to the Li Zicheng's rebels and then to Manchu Qing invaders, and the suicide of the last legitimate Ming emperor Zhu Youjian (the Chongzhen Emperor) in the spring 1644, the Ming Zhu Yousong, Prince of Fu was enthroned in Nanjing in June 1644 as the Hongguang Emperor.[38][39] His short reign was described by later historians as the first reign of the so-called Southern Ming dynasty.

Zhu Yousong, however, fared a lot worse than his ancestor Zhu Yuanzhang three centuries earlier. Beset by factional conflicts, his regime could not offer effective resistance to Manchu troops, when the Manchu army, led by Prince Dodo approached Jiangnan the next spring.[40] Days after Yangzhou fell to the Manchus in late May 1645, the Hongguang Emperor fled Nanjing, and the imperial Ming Palace was looted by local residents.[41] On June 6, Dodo's troops approached Nanjing, and the commander of the city's garrison, Zhao the Earl of Xincheng, promptly surrendered the city to them.[42][43] The Manchus soon ordered all male residents of the city to shave their heads in the Manchu queue way.[44] They requisitioned a large section of the city for the bannermen's cantonment, and destroyed the former imperial Ming Palace, but otherwise the city was spared the mass murders and destruction that befell Yangzhou.[45]

Qing Dynasty

Under the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the Nanjing area was known as Jiangning (江寧) and served as the seat of government for the Liangjiang Viceroy.[46] It had been visited by the Kangxi and Qianlong Emperors a number of times on their tours of the southern provinces.

Nanjing was invaded by British troops during the close of the First Opium War, which was ended by the Treaty of Nanking in 1842.

As the capital of the brief-lived Taiping Kingdom[47] in the mid-19th century, Nanjing was known as Tianjing (天京, "Heavenly Capital" or "Capital of Heaven") Both the Qing Viceroy and the Taiping king resided in buildings that would later be known as the Presidential Palace. When the Qing under Zeng Guofan retook the city in 1864, a massive slaughter occurred in the city with over 100,000 estimated to have committed suicide or fought to the death.[citation needed] Since the rebellion began, Imperial forces allowed no rebels speaking its dialect to surrender.[48] These policies of mass civilian murder occurred in Nanjing.[49]

Capital of the Republic

The Xinhai Revolution led to the founding of the Republic of China in January 1912 with Dr. Sun Yat-sen as the first provisional president and Nanking was selected as its new capital. However, the Qing Empire controlled large regions to the North, so revolutionaries asked Yuan Shikai to replace Sun as president in exchange for the last-Qing Emperor's abdication. Yuan demanded the capital be Beijing (closer to his power base).

In 1927, the Kuomintang (KMT) under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek again established Nanking as the capital of the Republic of China, and this became internationally recognized once KMT forces took Beijing in 1928. The following decade is known as the Nanking decade.

In 1937, Japan started full-scale invasion of China after invaded Manchuria in 1931, beginning the Second Sino-Japanese War (often considered a theatre of World War II).[50] Their troops occupied Nanjing in December and carried out the systematic and brutal Nanking massacre (the "Rape of Nanking").[51] Even children, the elderly, and nuns are reported to have suffered at the hands of the Imperial Japanese army.[52] The total death toll, including estimates made by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal, was between 300,000 and 350,000.[53] The Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall was built in 1985 to commemorate this event.

A few days before the fall of the city, the National Government of China was relocated to the southwestern city Chungking (now Chongqing) and resumed Chinese resistance. In 1940, a Japanese-collaborationist government known as the "Nanjing Regime" or "Nanjing Nationalist Government" led by Wang Jingwei was established in Nanjing as a rival to Chiang Kai-Shek's government in Chongqing. In 1946, after the Surrender of Japan, the KMT relocated its central government back to Nanjing.

People's Republic of China

On 21 April, Communist forces crossed the Yangtze River. On April 23, 1949, the People's Liberation Army conquered Nanjing.[54] The KMT government retreated to Canton (Guangzhou) until October 15, Chongqing until November 25, and then Chengdu before retreating to Taiwan on December 10. By late 1949, the People's Liberation Army was pursuing remnants of KMT forces southwards in southern China, and only Tibet was left. After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in October 1949, Nanjing was initially a province-level municipality, but it soon became the provincial capital of Jiangsu, and retains that status to this day.

Geography

Nanjing, with a total land area of 6,598 square kilometres (2,548 sq mi), is situated in one of the largest economic zones of China, the Yangtze River Delta, which is part of the downstream Yangtze River drainage basin. The Yangtze River flows past the west side of Nanjing City, while the Ningzheng Ridge surrounds the north, east and south side of the city. The city is 300 kilometres (190 mi) west-northwest of Shanghai, 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) south-southeast of Beijing, and 1,400 kilometres (870 mi) east-northeast of Chongqing.

Nanjing borders Yangzhou to the northeast, one town downstream when following the north bank of the Yangtze, Zhenjiang to the east, one town downstream when following the south bank of the Yangtze, and Changzhou to the southeast. On its western boundary is Anhui province, where Nanjing borders five prefecture-level cities.[55]

Nanjing is the intersection of Yangtze River—an east-west water transport artery and Nanjing–Beijing railway—a south-north land transport artery, hence the name “door of the east and west, throat of the south and north”. Furthermore, the west part of the Ningzhen range is in Nanjing; the Loong-like Zhong Mountain is curling in the east of the city; the tiger-like Stone Mountain is crouching in the west of the city, hence the name “the Zhong Mountain, a dragon curling, and the Stone Mountain, a tiger crouching”. Mr. Sun Yet-sen spoke highly of Nanjing in the “Constructive Scheme for Our Country”, “The position of Nanjing is wonderful since mountains, lakes and plains all integrated in it. It is hardly [sic] to find another city like this.”

Climate and environment

| Nanjing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nanjing has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) and is under the influence of the East Asian monsoon. The four seasons are distinct here, with damp conditions seen throughout the year, very hot and muggy summers, cold, damp winters, and in between, spring and autumn are of reasonable length. Along with Chongqing and Wuhan, Nanjing is traditionally referred to as one of the "Three Furnacelike Cities" along the Yangtze River (长江流域三大火炉) for the perennially high temperatures in the summertime.[57] However, the time from mid-June to the end of July is the plum blossom blooming season in which the meiyu (rainy season of East Asia; literally "plum rain") occurs, during which the city experiences a period of mild rain as well as dampness. Typhoons are uncommon but possible in the late stages of summer and early part of autumn. The annual mean temperature is around 15.46 °C (59.8 °F), with the monthly 24-hour average temperature ranging from 2.4 °C (36.3 °F) in January to 27.8 °C (82.0 °F) in July. The highest recorded temperature is 43.0 °C (109 °F), and the lowest −16.9 °C (2 °F).[58][59] On average precipitation falls 115 days out of the year, and the average annual rainfall is 1,062 millimetres (42 in). With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 37 percent in March to 52 percent in August, the city receives 1,983 hours of bright sunshine annually.

Nanjing is endowed with rich natural resources, which include more than 40 kinds of minerals. Among them, iron and sulfur reserves make up 40 percent of those of Jiangsu province. Its reserves of strontium rank first in East Asia and the South East Asia region. Nanjing also possesses abundant water resources, both from the Yangtze River and groundwater. In addition, it has several natural hot springs such as Tangshan Hot Spring in Jiangning and Tangquan Hot Spring in Pukou.

Surrounded by the Yangtze River and mountains, Nanjing also enjoys beautiful natural scenery. Natural lakes such as Xuanwu Lake and Mochou Lake are located in the centre of the city and are easily accessible to the public, while hills like Purple Mountain are covered with evergreens and oaks and host various historical and cultural sites. Sun Quan relocated his capital to Nanjing after Liu Bei's suggestion as Liu Bei was impressed by Nanjing's impeccable geographic position when negotiating an alliance with Sun Quan. Sun Quan then renamed the city from Moling (秣陵) to Jianye (建鄴) shortly thereafter.[60]

| Climate data for Nanjing (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.7 (89.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.1 (30.0) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

0.4 (32.7) |

11.6 (52.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37.4 (1.47) |

47.1 (1.85) |

81.8 (3.22) |

73.4 (2.89) |

102.1 (4.02) |

193.4 (7.61) |

185.5 (7.30) |

129.2 (5.09) |

72.1 (2.84) |

65.1 (2.56) |

50.8 (2.00) |

24.4 (0.96) |

1,062.3 (41.81) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 8.1 | 9.1 | 12.1 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 11.3 | 12.4 | 11.3 | 8.9 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 5.7 | 115.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 74 | 74 | 73 | 74 | 79 | 81 | 81 | 79 | 77 | 77 | 74 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 129.1 | 123.3 | 136.1 | 168.1 | 194.0 | 171.9 | 205.6 | 214.7 | 167.2 | 169.1 | 153.5 | 150.2 | 1,982.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41 | 40 | 37 | 44 | 46 | 41 | 47 | 52 | 45 | 48 | 49 | 48 | 45 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[56] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Environmental issues

Air pollution in 2013

A dense wave of smog began in the Central and Eastern part of China on 2 December 2013 across a distance of around 1,200 kilometres (750 mi),[61] including Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Anhui, Shanghai and Zhejiang. A lack of cold air flow, combined with slow-moving air masses carrying industrial emissions, collected airborne pollutants to form a thick layer of smog over the region.[62] The heavy smog heavily polluted central and southern Jiangsu Province, especially in and around Nanjing,[63] with its AQI pollution Index at "severely polluted" for five straight days and "heavily polluted" for nine.[64] On 3 December 2013, levels of PM2.5 particulate matter average over 943 micrograms per cubic metre,[65] falling to over 338 micrograms per cubic metre on 4 December 2013.[66] Between 3:00 pm, 3 December and 2:00pm, 4 December local time, several expressways from Nanjing to other Jiangsu cities were closed, stranding dozens of passenger buses in Zhongyangmen bus station.[63] From 5 to 6 December, Nanjing issued a red alert for air pollution and closed down all kindergarten through middle schools. Children's Hospital outpatient services increased by 33 percent; general incidence of bronchitis, pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections significantly increased.[67] The smog dissipated 12 December.[68] Officials blamed the dense pollution on lack of wind, automobile exhaust emissions under low air pressure, and coal-powered district heating system in North China region.[69] Prevailing winds blew low-hanging air masses of factory emissions (mostly SO2) towards China's east coast.[70]

Government

The full name of the government of Nanjing is "People's Government of Nanjing City". The city is under the one-party rule of the CPC, with the CPC Nanjing Committee Secretary as the de facto governor of the city and the mayor as the executive head of the government working under the secretary.

Administrative divisions

The sub-provincial city of Nanjing is divided into 11 districts.[71]

| Map | Subdivision | Simplified Chinese | Population (2010) | Area (km2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City Proper | |||||

| 1 | Xuanwu District | 玄武区 | 651,957 | 80.97 | |

| 2 | Qinhuai District | 秦淮区 | 1,007,922 | 50.36 | |

| 3 | Jianye District | 建邺区 | 426,999 | 82.00 | |

| 4 | Gulou District | 鼓楼区 | 1,271,191 | 57.62 | |

| 5 | Yuhuatai District | 雨花台区 | 391,285 | 131.90 | |

| 6 | Qixia District | 栖霞区 | 644,503 | 340.00 | |

| Suburban | |||||

| 7 | Jiangning District | 江宁区 | 1,145,628 | 1,573.00 | |

| 8 | Pukou District | 浦口区 | 710,298 | 913.00 | |

| 9 | Luhe District | 六合区 | 915,845 | 1,485.50 | |

| Rural | |||||

| 10 | Lishui District | 溧水区 | 421,323 | 983.00 | |

| 11 | Gaochun District | 高淳区 | 417,729 | 801.00 | |

- Defunct districts: Baixia District and Xiaguan District

Demographics

|

|

According to the Sixth China Census, the total population of the City of Nanjing reached 8.005 million in 2010. The statistics in 2011 estimated the total population to be 8.11 million. The birth rate was 8.86 percent and the death rate was 6.88 percent. The urban area had a population of 6.47 million people.

As in most of eastern China the ethnic makeup of Nanjing is predominantly Han nationality (98.56 percent), with 50 other minority nationalities. In 1999, 77,394 residents belonged to minority nationalities, among which the vast majority (64,832) were Hui nationalities, contributing 83.76 percent to the minority population. The second and third largest minority groups were Manchu (2,311) and Zhuang (533) nationalities. Most of the minority nationalities resided in Jianye District, comprising 9.13 percent of the district's population.[73]

In 2010 the sex ratio of the city population was 107.31 males to 100 females.[74][75]

Economy

Earlier development

Since the Three Kingdoms period, Nanjing has become an industrial centre for textile and mint owing to its strategic geographical location and convenient transportation. During the Ming dynasty, Nanjing's industry was further expanded, and the city became one of the most prosperous cities in China and even the world. It led in textile, mint, printing, shipbuilding and many other industries, and was the busiest business center in the Far East.

Into the first half of the twentieth century, Nanjing gradually shifted from a production hub into a heavy consumption city, mainly because of the rapid expansion of the wealthy population after Nanjing once again regained the political spotlight of China. A number of huge department stores such as Zhongyang Shangchang sprouted up, attracting merchants from all over China to sell their products in Nanjing. In 1933, the revenue generated by the food and entertainment industry in the city exceeded the sum of the output of the manufacturing and agriculture industry. One third of the city population worked in the service industry, while prostitution, drugs and gambling also thrived.

In the 1950s, the CPC invested heavily in Nanjing to build a series of state-owned heavy industries, as part of the national plan of rapid industrialization. Electrical, mechanical, chemical and steel factories were established successively, converting Nanjing into a heavy industry production centre of East China.[76] Overenthusiastic in building a “world-class” industrial city, leaders of Nanjing also made many disastrous mistakes during the development, such as spending hundreds of millions of yuan to mine for non-existent coal, resulting in the negative economic growth in the late 1960s.

Today

The current industry of the city basically inherited the characteristics of the 1960s, with electronics, cars, petrochemical, iron and steel, and power as the "Five Pillar Industries". Some representative big state-owned firms are Panda Electronics, Jincheng Motors and Nanjing Steel. The tertiary industry also regained prominence, accounting for 44 percent of the GDP of the city. The city is also vying for foreign investment against neighboring cities in the Yangtze River Delta, and so far a number of famous multinational firms, such as Volkswagen Group, Iveco, A.O. Smith, and Sharp, have established their lines there. Since China's entry into the WTO, Nanjing has received increasing attention from foreign investors, and on average two new foreign firms establish offices in the city every day.

The city government is further improving the desirability of the city to investors by building large industrial parks, which now total four: Gaoxin, Xingang, Huagong and Jiangning. Despite the effort, Nanjing's Gross Domestic Product is still falling behind that of other neighbouring cities such as Suzhou, Wuxi and Hangzhou, which have an edge in attracting foreign investment and local innovation. In addition, the traditional state-owned enterprises find themselves incapable of competing with efficient multinational firms, and hence are either mired in heavy debt or forced into bankruptcy or privatization. This has resulted in large numbers of layoff workers who are technically not unemployed but effectively jobless.

In recent years, Nanjing has been developing its economy, commerce, industry, as well as city construction. In 2010 the city's GDP was RMB 501 billion (3rd in Jiangsu), and GDP per capita was RMB 65,490, a 13 percent increase from 2009. The average urban resident's disposable income was RMB 28,312, while the average rural resident's net income was RMB 11,050. The registered urban unemployment rate was 3.02 percent, lower than the national average (4.3 percent). Nanjing's Gross Domestic Product ranked 14th in 2010 in China, and its overall competence ranked 6th in mainland and 8th including Taiwan and Hong Kong in 2009.[77]

Industrial zones

- Nanjing Baixia Hi-Tech Industrial Zone

Nanjing Baixia Hi-Tech Industrial Zone is a national hi-tech industrial zone with 16.5 square kilometres (6.4 sq mi) planned area. The zone is only 13.5 km (8.4 mi) away from Nanjing downtown and 50 km (31 mi) away from Nanjing Lukou Airport. Several expressways pass through here. It is well equipped with comprehensive facilities, and it provides a good investment environment for high-tech industries. Electronic industry, automobile, chemical, machinery, instruments and building materials are the encouraged industries in the zone.[78]

- Nanjing Economic and Technological Development Zone

Established in 1992, Nanjing Economic and Technological Development Zone is a national level zone surrounded by convenient transportation network. It is only 20 km (12 mi) away from Nanjing Port and 40 km (25 mi) away from Nanjing Lukou Airport. It is well equipped with basic facilities like electricity, water, communication, gas, steam and so on. It has formed four specialized industries, which are electronic information, bio-pharmaceutical, machinery and new materials industry.[79]

- Nanjing Export Processing Zone

On March 10, 2003 the State Council approved the establishment of this Export Processing Zone (EPZ) in Nanjing's Southern District. This EPZ is free from import/export duty area and provides 24-hour customs-bonded conditions. It has a planned area of 3 km2 (1.2 sq mi). The Central Government has given the special economic region preferential policies to attract more enterprises engaged in processing trade investment in the region. It is only 20 km (12 mi) from Nanjing Port and several expressways pass through here.[80]

- Nanjing New and High-Tech Industry Development Zone

Nanjing New and High-Tech Industry Development Zone was jointly founded by Jiangsu Provincial People's Government and Nanjing Municipal People's Government, and started to break ground of construction on September 1, 1988. It was established as a national new and high-tech industry development zone by the State Council on March 6, 1991. The zone is next to National Highway 104 and 312. Its pillar industries include electronic information, bio-engineering and pharmaceutical industry.[81]

Transportation

Nanjing is the transportation hub in eastern China and the downstream Yangtze River area. Different means of transportation constitute a three-dimensional transport system that includes land, water and air. As in most other Chinese cities, public transportation is the dominant mode of travel of the majority of the citizens. The city now has four bridge or tunnel crossings spanning the Yangtze, which are tying districts north of the river with the city centre on the south bank. See also Transport in Nanjing.

Rail

Nanjing is an important railway hub in eastern China.[82] It serves as rail junction for the Beijing-Shanghai (Jinghu) (which is itself composed of the old Jinpu and Huning Railways), Nanjing–Tongling (Ningtong), Nanjing–Qidong (Ningqi), and the Nanjing-Xian (Ningxi) which encompasses the Hefei–Nanjing Railway. Nanjing is connected to the national high-speed railway network by Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway and Shanghai–Wuhan–Chengdu Passenger Dedicated Line, with several more high-speed rail lines under construction.

Among all 17 railway stations in Nanjing, passenger rail service is mainly provided by Nanjing Railway Station and Nanjing South Railway Station, while other stations like Nanjing West Railway Station, Zhonghuamen Railway Station and Xianlin Railway Station serve minor roles. Nanjing Railway Station was first built in 1968.[83] In 1999, On November 12, 1999, the station was burnt in a serious fire.[84] Reconstruction of the station was finished on September 1, 2005. Nanjing South Railway Station, which is one of the 5 hub stations on Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway, has officially been claimed as the largest railway station in Asia and the second largest in the world in terms of GFA (Gross Floor Area).[85] Construction of Nanjing South Station began on 10 January 2008.[86] The station was opened for public service in 2011.[87]

Road

As an important regional hub in the Yangtze River Delta, Nanjing is well-connected by over 60 state and provincial highways to all parts of China.

Express highways such as Hu–Ning, Ning–He, Ning–Hang enable commuters to travel to Shanghai, Hefei, Hangzhou, and other important cities quickly and conveniently. Inside the city of Nanjing, there are 230 km (140 mi) of highways, with a highway coverage density of 3.38 kilometres per hundred square kilometrs (5.44 mi/100 sq mi). The total road coverage density of the city is 112.56 kilometres per hundred square kilometres (181.15 mi/100 sq mi).[88]

Nanjing Sample Technology Company Limited is a major provider of Intelligent traffic systems.[89]

Expressways:

- G25 Changchun–Shenzhen Expressway

- G36 Nanjing–Luoyang Expressway

- G40 Shanghai–Xi'an Expressway

- G42 Shanghai–Chengdu Expressway

- G4211 Nanjing–Wuhu Expressway, a spur of G42 that extends west to Wuhu, Anhui

- S55 Nanjing–Gaochun Expressway

- S38 Yanjiang Expressway

- G2501 Nanjing Ring Expressway

National Highway (GXXX):

- China National Highway 104—motorists can either drive northwest to Beijing or south to Fuzhou, Fujian.

- China National Highway 205—motorists can either drive north to Shanhaiguan, Hebei or south to Shenzhen, Guangdong.

- China National Highway 312—motorists can either drive east to Shanghai or west to Khorgas, Xinjiang on the Kazakh border

- China National Highway 328—Nanjing is the western terminus of G328, which motorists can follow to Hai'an County in eastern Jiangsu

Public transportation

The city also boasts an efficient network of public transportation, which mainly consists of bus, taxi and metro systems. The bus network, which is currently run by 3 companies since 2011, provides more than 370 routes covering all parts of the city and suburban areas.[90] Nanjing Metro Line 1, started service on September 3, 2005, with 16 stations and a length of 21.72 km.[91] Line 2 and the 24.5 km-long south extension of Line 1 officially opened to passenger service on May 28, 2010.[92][93] The city is planning to complete a 17-line Metro and light-rail system by 2030.[94] The expansion of the Metro network will greatly facilitate the intracity transportation and reduce the currently heavy traffic congestion.

Air

Nanjing's airport, Lukou International Airport, serves both national and international flights. In 2013, Nanjing airport handled 15,011,792 passengers and 255,788.6 tonnes of freight.[95] The airport currently has 85 routes to national and international destinations, which include Japan, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Germany. The airport is connected by a 29-kilometre (18 mi) highway directly to the city center, and is also linked to various intercity highways, making it accessible to the passengers from the surrounding cities. A railway Ninggao Intercity Line is being built to link the airport with Nanjing South Railway Station.[96] Lukou Airport was opened on 28 June 1997, replacing Nanjing Dajiaochang Airport as the main airport serving Nanjing. Dajiaochang Airport is still used as a military air base.[97]

Water

Port of Nanjing is the largest inland port in China, with annual cargo tonnage reached 191,970,000 t in 2012.[98] The port area is 98 kilometres (61 mi) in length and has 64 berths including 16 berths for ships with a tonnage of more than 10,000.[99] Nanjing is also the biggest container port along the Yangtze River; in March 2004, the one million container-capacity base, Longtan Containers Port Area opened, further consolidating Nanjing as the leading port in the region. In the 1960s the first Yangtze river bridge was completed, becoming almost the only solid connection between North and South in eastern China at that time. The bridge became a source of pride and an important symbol of modern China, having been built and designed by the Chinese themselves following failed surveys by other nations and the reliance on and then rejection of Soviet expertise. Begun in 1960 and opened to traffic in 1968, the bridge is a two-tiered road and rail design spanning 4,600 metres on the upper deck, with approximately 1,580 metres spanning the river itself. As of 2010, it operated six public ports and three industrial ports.[100]

Culture and art

Being one of the four ancient capitals of China, Nanjing has always been a cultural centre attracting intellectuals from all over the country. In the Tang and Song dynasties, Nanjing was a place where poets gathered and composed poems reminiscent of its luxurious past; during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the city was the official imperial examination centre (Jiangnan Examination Hall) for the Jiangnan region, again acting as a hub where different thoughts and opinions converged and thrived.

Today, with a long cultural tradition and strong support from local educational institutions, Nanjing is commonly viewed as a “city of culture” and one of the more pleasant cities to live in China.

Art

Some of the leading art groups of China are based in Nanjing; they include the Qianxian Dance Company, Nanjing Dance Company, Jiangsu Peking Opera Institute and Nanjing Xiaohonghua Art Company among others.

Jiangsu Province Kun Opera is one of the best theatres for Kunqu, China's oldest stage art.[101] It is considered a conservative and traditional troupe. Nanjing also has professional opera troupes for the Yang, Yue (shaoxing), Xi and Jing (Chinese opera varieties) as well as Suzhou pingtan, spoken theatre and puppet theatre.

Jiangsu Art Gallery is the largest gallery in Jiangsu Province, presenting some of the best traditional and contemporary art pieces of China;[102] many other smaller-scale galleries, such as Red Chamber Art Garden and Jinling Stone Gallery, also have their own special exhibitions.

Festivals

Many traditional festivals and customs were observed in the old times, which included climbing the City Wall on January 16, bathing in Qing Xi on March 3, hill hiking on September 9 and others (the dates are in Chinese lunar calendar). Almost none of them, however, are still celebrated by modern Nanjingese.

Instead, Nanjing, as a popular tourist destination, hosts a series of government-organised events throughout the year. The annual International Plum Blossom Festival held in Plum Blossom Hill, the largest plum collection in China, attracts thousands of tourists both domestically and internationally. Other events include Nanjing Baima Peach Blossom and Kite Festival, Jiangxin Zhou Fruit Festival and Linggu Temple Sweet Osmanthus Festival.

Libraries

Nanjing Library, founded in 1907, houses more than 7 million volumes of printed materials and is the third largest library in China, after the National Library in Beijing and Shanghai Library. Other libraries, such as city-owned Jinling Library and various district libraries, also provide considerable amount of information to citizens. Nanjing University Library, owned by Nanjing University, with a collection of 4.2 million volumes, is the second largest university libraries in China after Peking University Library. More than 100 multimedia networked-computers are available to readers.

Museums

Nanjing has some of the oldest and finest museums in China. Nanjing Museum, formerly known as National Central Museum under KMT rule, is the first modern museum and remains as one of the leading museums in China having 400,000 items in its permanent collection,.[103] The museum is notable for enormous collections of Ming and Qing imperial porcelain, which is among the largest in the world.[104] Other museums include the China Modern History Museum in the Presidential Palace, the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, the City Museum of Nanjing, the Taiping Kingdom History Museum, the Nanjing Customs Museum, the Nanjing City Wall Cultural Museum, and a small museum and tomb honoring the 15th century seafaring admiral Zheng He although his body was buried at sea off the Malabar Coast near Calicut in western India.[105]

Theatre

Most of Nanjing's major theatres are multi-purpose, used as convention halls, cinemas, musical halls and theatres on different occasions. The major theatres include the People's Convention Hall and the Nanjing Arts and Culture Center.

Night life

Traditionally Nanjing's nightlife was mostly centered around Nanjing Fuzimiao (Confucius Temple) area along the Qinhuai River, where night markets, restaurants and pubs thrived.[106] Boating at night in the river was a main attraction of the city. Thus, one can see the statues of the famous teachers and educators of the past not too far from those of the courtesans who educated the young men in the other arts.

In the past 20 years, several commercial streets have been developed, hence the nightlife has become more diverse: there are shopping malls opening late in the Xinjiekou CBD and Hunan Road. The well-established "Nanjing 1912" district hosts a wide variety of pastime facilities ranging from traditional restaurants and western pubs to dance clubs. There are two major areas where bars are densely located; one is in 1912 block; the other is along Shanghai road and its neighbourhood. Both are popular with international residents of the city.

These days, the most comprehensive source of nightlife information (in English) can be found on HelloNanjing.net and NanjingExpat.com.

Local people still very much enjoy street food, such as Turkish Kebab. As elsewhere in Asia, Karaoke is popular with both young and old crowd.

Food and symbolism

The radish is also a typical food representing people of Nanjing, which has been spread through word of mouth as an interesting fact for many years in China. According to Nanjing.GOV.cn, "There is a long history of growing radish in Nanjing especially the southern suburb. In the spring, the radish tastes very juicy and sweet. It is well-known that people in Nanjing like eating radish. And the people are even addressed as 'Nanjing big radish', which means they are unsophisticated, passionate and conservative. From health perspective, eating radish can help to offset the stodgy food that people take during the Spring Festival".[107]

Sports and stadiums

As a major Chinese city, Nanjing is home to many professional sports teams. Jiangsu Sainty, the football club currently staying in Chinese Super League, is a long-term tenant of Nanjing Olympic Sports Center. Jiangsu Nangang Basketball Club is a competitive team which has long been one of the major clubs fighting for the title in China top level league, CBA. Jiangsu Volleyball men and women teams are also traditionally considered as at top level in China volleyball league.

There are two major sports centers in Nanjing, Wutaishan Sports Center and Nanjing Olympic Sports Center. Both of these two are comprehensive sports centers, including stadium, gymnasium, natatorium, tennis court, etc. Wutaishan Sports Center was established in 1952 and it was one of the oldest and most advanced stadiums in early time of People's Republic of China. Nanjing hosted the 10th National Games of P.R.C. in 2005 and will host the 2nd summer Youth Olympic Games in 2014.[108][109]

In 2005, in order to host The 10th National Game of People's Republic of China, there was a new stadium, Nanjing Olympic Sports Center, constructed in Nanjing. Compared to Wutaishan Sports Center, which the major stadium's capacity is 18,500.,[110] Nanjing Olympic Sports Center has a more advanced stadium which is big enough to seat 60,000 spectators. Its gymnasium has capacity of 13,000, and natatorium of capacity 3,000.

Tourism

Nanjing is one of the most beautiful cities of mainland China with lush green parks, natural scenic lakes, small mountains, historical buildings and monuments, relics and much more, which attracts thousands of tourists every year.

Buildings and monuments

Imperial period

- Stone City

- Qixia Temple

- Linggu Temple

- Jiming Temple

- South Tang mausoleums (南唐二陵)

- Fuzimiao (Confucius Temple) and Qinhuai River

- Jiangnan Gongyuan

- City Wall of Nanjing

- Ming Dynasty Palace Site

- Chaotian Palace

- Drum Tower of Nanjing

- Beiji Ge

- Jinghai Temple

- Zhonghua Gate

- The Porcelain Pagoda of Nanjing (demolished)

- Xu Garden

- Zhan Yuan Garden

- Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum and its surrounding complex

- Yangshan Quarry

- Yuejiang Lou

Republic of China period

Because it was designated as the national capital, many structures were built around that time. Even today, some of them still remain which are open to tourists.

- Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum and its surrounding area

- Former Presidential Palace, Nanjing of ROC

- Former Central Government of ROC Building Group along N. Zhongshan Road (中山北路国民政府建筑)

- Former Central Committee of KMT Buildings (中国国民党中央党部旧址)

- Jiangsu Art Gallery (Former National Art Gallery Buildings)

- Nanjing Great Hall of the People (Former National Great Hall)

- Former Foreign Embassies in Gulou Area (鼓楼使馆区)

- Nanking Officials Residence Cluster along Yihe Road (颐和路公馆区)

- Former Central Stadium(Nanjing Physical Education Institute) (中央体育场旧址/南京体育学院)

- Former Central Radio of KMT Building

- Republic of China Military Academy Buildings (中央陆军军官学校旧址)

- Former Bank of China Nanking Branch Building (中国银行南京分行旧址)

- Former Bank of Communications Nanking Branch Building (交通银行南京分行旧址)

- Former Central Bank of ROC Nanking Branch Building (中央银行南京分行旧址)

- Dahua Theatre (大华电影院)

- Lizhishe Buildings (励志社)

- Former Macklin Hospital Buildings (Gulou Hospital) (马林医院旧址/鼓楼医院)

- Former Central Hospital Buildings (国立中央医院旧址)

- Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall

- Former National Central Museum Buildings (Nanjing Museum) (国立中央博物院旧址/南京博物馆)

- Purple Mountain Observatory

- Former Academia Sinica of ROC Buildings (国立中央研究院旧址)

- Former Central University Buildings (Southeast University)

- Former University of Nanking Buildings (Nanjing University)

- Former Ginling College Buildings(Nanjing Normal University)

- St. Paul's Church (圣保罗堂)

- Central Hotel (中央饭店)

- Former Capital Hotel (Huajiang Hotel) (首都饭店/华江饭店)

- Yangtse Hotel (扬子饭店)

- Sun Yat-sen Zoo (中山动物园)

People's Republic of China period

Parks and gardens

- China Gate Castle Park

- Couple Park

- Defence Park

- Gulin Park

- Mochou Lake and Park

- Nanjing Hongshan Forest Zoo

- Purple Mountain Scenic Area

- Qingliangshan Park

- Taoye Ferry

- White Horse Park

- Wuchaomen Park

- Xiamafang Ruins Park

- Xu Garden

- Xuanwu Lake

- Yuhuatai Memorial Park of Revolutionary Martyrs

- Zhan Yuan Garden

- Zhongshan Botanical Garden

Other places of interest

- Tangshan Hot Spring

- Jiangxin Island

- Yangtze River power line crossings, tallest electricity pylons built of concrete.

Education

Nanjing has been the educational centre in southern China for more than 1700 years. Currently, it boasts of some of the most prominent educational institutions in the region, which are listed as follows:

National universities and colleges

Operated by Ministry of Education

- China Pharmaceutical University

- Hohai University

- Nanjing Agricultural University

- Nanjing University

- Southeast University

Operated by Ministry of Industry and Information Technology

Operated by the joint Commission of the State Forest Administration and Public Order Ministry

- Nanjing Forest Police College (南京森林公安高等专科学校)

Operated by the general sport Administration

- Nanjing Sport Institute (南京体育学院)

National military universities and colleges

- PLA Nanjing Army Command College (中国人民解放军南京陆军指挥学院)

- PLA Nanjing International Relation College (中国人民解放军南京国际关系学院)

- PLA Nanjing Political College (中国人民解放军南京政治学院)

- PLA Naval Command College (中国人民解放军海军指挥学院)

- PLA University of Science and Technology (中国人民解放军理工大学)

Provincial universities and colleges

- Jiangsu Institute of Education

- Jinling Institute of Technology (金陵科技学院)

- Nanjing Arts Institute (南京艺术学院)

- Nanjing Audit University

- Nanjing City Vocational College (南京城市职业学院)

- Nanjing Forestry University

- Nanjing Institute of Technology

- Nanjing Medical University

- Nanjing Normal University

- Nanjing Xiaozhuang University (南京晓庄学院)

- Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine

- Nanjing University of Finance and Economics

- Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology

- Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications

- Nanjing University of Technology

Private universities and colleges

- Communication University Of China' Nanjing (中国传媒大学南广学院)

- Hopkins-Nanjing Center

- Nanjing University Jinling College (南京大学金陵学院)

- New York Institute of Technology

- Sanjiang College

Notable high schools

- High School Affiliated to Nanjing Normal University

- Jinling High School

- Nanjing Foreign Language School

- Nanjing International School

- Nanjing Ninghai High School (南京宁海中学)

- Nanjing No. 1 High School (南京第一中学)

- Nanjing No. 9 High School (南京第九中学)

- Nanjing No. 13 High School (南京市第十三中学)

- Nanjing No. 29 High School (南京市第二十九中学)

- Nanjing Zhonghua High School

See also

- Treaty of Nanjing

- Nanjing Massacre

- Nanjing Salted Duck

- The Rape of Nanking (book)

- Jiangnan

- List of cities in the People's Republic of China by population

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

Notes

- ^ "A Grass Roots Fight to Save a 'Super Tree'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ "Illuminating China's Provinces, Municipalities and Autonomous Regions". PRC Central Government Official Website. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ^ "南京历史沿革". 中国南京政府官网.

- ^ "Romanisation of the Chinese Language". Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- ^ "走马南京都市圈". 中国经济快讯周刊/人民网. 2003.

- ^ "南京介绍". 新华网. 2012-10-09.

- ^ "江苏省行政区划介绍". 江苏省政府官网.

- ^ Rita Yi Man Li, "A Study on the Impact of Culture, Economic, History and Legal Systems Which Affect the Provisions of Fittings by Residential Developers in Boston, Hong Kong and Nanjing," Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal. 1:3-4. 2009. Access via Questia, an online subscription service.

- ^ a b Crespigny 2004, 3.

- ^ "南京市". 重編囯語辭典修訂本. Ministry of Education, ROC.

民國十六年,國民政府宣言定為首都,今以臺北市為我國中央政府所在地。(In the 16th Year of the Republic of China [1927], the National Government established [Nanking] as the capital. At present, Taipei is the seat of the central government.)

- ^ 薛宏莉 (2008-05-07). "15个副省级城市中 哈尔滨市房价涨幅排列第五名". 哈尔滨地产 (in Chinese). Sohu. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "中央机构编制委员会印发《关于副省级市若干问题的意见》的通知. 中编发[1995]5号". 豆丁网. 1995-02-19. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- ^ Shokoohi, Kimiya. "See You in Nanjing in 2014". nternational Olympic Committee. nternational Olympic Committee. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ "《南京市2011年度人口发展报告》正式发布". 南报网. 2012-05-06.

- ^ http://finance.china.com.cn/roll/20130321/1342329.shtml

- ^ "2015年南京常住人口将突破830万". 扬子晚报. 2013-05-15.

- ^ 南京市人口和计划生育委员会,南京市统计局. 2012年度南京市人口发展报告. 2013-04-28

- ^ "Home - Women GP - Nanjing". Nanjing2009.fide.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ^ "南京六朝石刻现状调查:在田野与工地间寻找国宝" (in Chinese). Xinhua. 7 June 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ "六朝名都崛起江东". 南京市志(第1册).

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ 《金陵记》:“梁都之时,城中二十八万户,西至石头,东至倪塘,南至石子冈,北过蒋山,东西南北各四十里。” Template:Zh icon

- ^ Liang Baiquan. Nanjing-de Liu Chao Shike (Nanjing's Six Dynasties' Sculptures). pp. 53–54. ISBN 7-80614-376-9Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Albert E. Dien, Six Dynasties Civilization. Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-300-07404-2. Partial text on Google Books. P. 190. A reconstruction of the original form of the ensemble is shown in Fig. 5.19.

- ^ "梁安成康王萧秀墓石刻". Jllib.org.cn. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ "南唐再兴金陵城". 南京市志(第1册).

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Johannes L. Kurz, (2011). China's Southern Tang Dynasty, 937-976. Routledge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Franke, Herbert (1994). "The Chin dynasty". In Denis Twitchett, Denis C.; John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ^ Tao, Jing-Shen (2009). "The Move to the South and the Reign of Kao-tsung". In Paul Jakov Smith; Denis C. Twitchett (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 5, The Sung Dynasty and Its Precursors, 907-1279. Cambridge University Press. p. 647. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1.

- ^ "隋唐州县南唐国都". 南京市志(第1册).

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Ebrey (1999), 191.

- ^ Chinese Walled Cities 221 BC-AD 1644. Osprey Publishing. 2009. p. 61. ISBN 1-84603-381-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Ansight Guides (1997). Insight Guides: China 5/E. Apa Publications, original from Pennsylvania State University. p. 268. ISBN 0-395-66287-7.

- ^ "Largest Cities Through History". Geography.about.com. 2013-11-14. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ Jonathan D. Spence. God's Chinese Son, New York 1996

- ^ Williams, S. Wells. The Middle Kingdom: a Survey of the Geography, Government, Literature, Social Life, Arts, & History of the Chinese Empire & its Inhabitants, Vol. 1. Scribner (New York), 1904.

- ^ Yang & Lu 2001, pp. 616–617

- ^ Johannes L. Kurz, "Boni in Chinese Sources: Translations of Relevant Texts from the Song to the Qing Dynasties", Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Working Paper No 4 (July 2011),

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 346.

- ^ Struve 1988, p. 644.

- ^ Struve (1993), p.55–56

- ^ Struve (1993), pp. 60–61

- ^ Struve (1993), pp. 62–63

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 578.

- ^ Wakeman 1985, p. 647; Struve 1988, p. 662; Dennerline 2002, p. 87 (which calls this edict "the most untimely promulgation of [Dorgon's] career."

- ^ Struve (1993), pp. 64–65, 72

- ^ "清督驻所太平天国定鼎". 南京市志(第1册).

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Publicado por Eduardo Real. "Eduardo Real: The Taiping Rebellion". Dangeroustravel.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ^ Ho Ping-ti. STUDIES ON THE POPULATION OF CHINA, 1368–1953. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959. p. 237

- ^ Pelissier, Roger. THE AWAKENING OF CHINA: 1793–1949. Edited and Translated by Martin Kieffer. New York: Putnam, 1967. p. 109

- ^ Fu Jing-hui, An Introduction of Chinese and Foreign History of War, 2003, p.109–111

- ^ John E. Woods, The Good Man of Nanking, the Diaries of John Rabe, 1998 P. 275-278

- ^ John E. Woods, The Good Man of Nanking, the Diaries of John Rabe, 1998 P. 275-278, 281

- ^ Document sent by former Japanese foreign minister Hirota Koki to the Japanese Embassy in Washington on January 17, 1938, (Ref. National Archives, Washington, D.C., Released in Sept. 1994.)

- ^ Zhang, Chunhou. Vaughan, C. Edwin. [2002] (2002). Mao Zedong as Poet and Revolutionary Leader: Social and Historical Perspectives. Lexington books. ISBN 0-7391-0406-3. p 65, p 58

- ^ "中华人民共和国成立后中央直辖市及江苏省省会". 南京市志(第1册).

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ a b "中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年)" (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- ^ "三大火炉完全名不副实 三城市拒绝再称"火炉"". Xinhua Net. 2005-06-25. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- ^ "南京气象资料". 中国气象科学数据共享服务网. Retrieved 2013年5月.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ^ Zizhi Tongjian, vols. 66, 94.

- ^ "Smog Shrouds Eastern China". Earth Observatory. 10 December 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ "Smog and fog hit east, north China". Xinhua News Agency. 6 December 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ a b 吴怡、刘伟伟. "我国25个省现雾霾 江苏成污染重灾区全国最严重". 腾讯转现代快报.

- ^ "Environmental officials deny blame for eastern China smog". China Dialogue. 6 January 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ "长三角遭遇重度霾 专家称石油化工和尾气是主因". 人民网(转载自《新京报》). 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-12-13.

- ^ Liu Chen-yao. "中国出现入冬以来最大范围雾霾 局地严重污染 (Smog levels in China reach record levels since the end of 2013; surrounding areas severely polluted" (in Chinese). China news agency.

- ^ 孙莹. "雾霾天南京学校停课 儿童医院门诊量上升三分之一". 新华网.

- ^ "12日后受冷空气和降雨影响 南方大范围雾霾将告一段落". 上海政府网.

- ^ 综合本报和新华社电. "三问今冬十面"霾"伏". 人民日报海外版.

- ^ "Map: Shanghai's off the charts air pollution". Greenpeace. 6 December 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ "2013年江苏省行政区划". 行政区划网. 2013-02-20.

- ^ 南京市统计局 (2013.08). 《南京统计年鉴2013》. 中国统计出版社. ISBN 978-7-5037-6859-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "南京民族概况". 南京市民族宗教事务局. 2012-08-26.

- ^ 刘绍武 (2011-11). 中华人民共和国全国分县市人口统计资料. 群众出版社. ISBN 9787501449170.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "南京市2010年第六次全国人口普查主要数据公报". 南京市第六次全国人口普查领导小组办公室,南京市统计局. 2011-05-03.

- ^ "综述". 南京市志(第5卷)·工业.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "南京总部经济发展能力居全国第六". 新华报业网(来源:南京日报). 2009-10-19.

- ^ "Nanjing Baixia Hi-Tech Industrial Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ "Nanjing Economic and Technological Development Zone - China Economic Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ "Nanjing Export Processing Zone | China EPZ | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. 2003-03-10. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ "Nanjing Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ^ "伴随江苏铁路发展 南京将成长三角铁路交通枢纽". 新华日报. 2009-07-15.

- ^ a b "车站简介". 南京火车站. 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ "南京火车站12日晨发生特大火灾". 新浪网. 1999. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ "南京火车站和北京南站变身 成全国新建改建范本". 火车网. 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ 中國評論新聞:京滬高鐵南京南站開工 將建亞洲第一大站

- ^ 亞洲最大 京滬高鐵南京南站啟用 - 聯合報

- ^ "数字交通". 南京市交通局. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ http://en.acnnewswire.com/Article.Asp?Art_ID=2030&lang=EN

- ^ "南京三大公交企业新名称敲定". 凤凰网. 2012-06-26.

- ^ "Nanjing metro inaugurated". Railway Gazette International. 2005-10-01.

- ^ "Nanjing Metro places €85·5m train order". Railway Gazette International. 2008-01-25.

- ^ 南京地铁二号线载人模拟运营, Sina News. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ 南京轨道交通线网共17条; Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ^ "2013年华东机场生产数据排序" (in Mandarin). Civil Aviation Administration of China East China Regional Administration. 2014-03-06. Retrieved 2014-03-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ 南京开建地铁机场线 第一次地铁将抵达机场. 中国江苏网,2011-12-28

- ^ "大校场机场". Nanjing City Chronicles (in Chinese). Nanjing City Government. Retrieved 2012-09-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "2012全国货物、集装箱、旅客吞吐量统计". www.chinaports.com. 南京港(集团)有限公司. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ "集团简介". www.njp.com.cn. 中国港口网. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ "The Brief Introduction of Nanjing Port".

- ^ A brief introduction to Jiangsu Province Kunqu Theatre

- ^ Jiangsu Art Gallery, Synotrip.

- ^ "Treasures in Nanjing Museum". Chinaculture.org. 2008-07-14. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ^ "Porcelain Creatures Highlight Nanjing Museum". China.org.cn. 2003-10-29. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ^ Levathes, Louise. When China Ruled The Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne 1405-1433, p. 172. Oxford Univ. Press (New York), 1996.

- ^ Life on the Water's Edge: The Culture and History of the Qinhuai River - China.org.cn

- ^ "Frying Spring Rolls at the Beginning of Spring". Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "南京成功获得2014年夏季世界青年奥运会主办权". 中国日报. 2010-02-11.

- ^ "南京获得2013年亚青会举办权". 腾讯网. 2010-11-13.

- ^ Wutaishan Stadium

References

- Cotterell, Arthur. (2007). The Imperial Capitals of China - An Inside View of the Celestial Empire. London: Pimlico. pp. 304 pages. ISBN 978-1-84595-009-5.

- Danielson, Eric N. (2004). Nanjing and the Lower Yangzi River. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish/Times Editions. ISBN 981-232-598-0.

- Eigner, Julius (February 1938). "The Rise and Fall of Nanking" in National Geographic Vol. LXXIII No.2. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic.

- Farmer, Edward L. (1976). Early Ming Government: The Evolution of Dual Capitals. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Hobart, Alice Tisdale (1927). Within the Walls of Nanking. New York: MacMillan.

- Jiang, Zanchu (1995). Nanjing shi hua. Nanjing: Nanjing chu ban she. ISBN 7-80614-159-6.

- Lutz, Jessie Gregory (1971). China and the Christian Colleges, 1850-1950. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Ma, Chao Chun (Ma Chaojun) (1937). Nanking's Development, 1927-1937. Nanking: Municipality of Nanking.

- Michael, Franz (1972). The Taiping Rebellion: History and Documents (3 vols.). Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1977). "The Transformation of Nanking, 1350–1400," in The City in Late Imperial China, ed. by G. William Skinner. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Mote, Frederick W., and Twitchett, Denis, ed. (1988). The Cambridge History of China Vol. 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Musgrove, Charles D. (2000). "Constructing a National Capital in Nanjing, 1927–1937," in Remaking the Chinese City, 1900–1950, ed. by Joseph W. Esherick. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Nanking Women's Club (1933). Sketches of Nanking. Nanking: Nanking Women's Club.

- Ouchterlony, John (1844). The Chinese War: An Account of All the Operations of the British Forces from the Commencement to the Treaty of Nanking. London: Saunders and Otley.

- Prip-Moller, Johannes (1935). "The Hall of Lin Ku Ssu (Ling Gu Si) Nanking," in Artes Monuments Vol. III. Copenhagen: Artes Monuments.

- Smalley, Martha L. (1982). Guide to the Archives of the United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia (Record Group 11). New Haven: Yale University Divinity Library Special Collections.

- Struve, Lynn (1988), "The Southern Ming", in Frederic W. Mote, Denis Twitchett, and John King Fairbank (eds.) (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 641–725

{{citation}}:|editor-last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link). - Struve, Lynn A. (1998). Voices from the Ming-Qing Cataclysm: China in Tigers' Jaws. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07553-7. (Chapter 4: "The emperor really has left": Nanjing changes hands, pp. 55–72.)

- Teng, Ssu Yu (1944). Chang Hsi (Zhang Xi) and the Treaty of Nanking, 1842. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Thurston, Mrs. Lawrence (Matilda) (1955). Ginling College. New York: United Board for Christian Colleges in China.

- Till, Barry (1982). In Search of Old Nanking. Hong Kong: Hong Kong and Shanghai Joint Publishing Company.

- Tyau, T.Z. (1930). Two Years of Nationalist China. Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh.

- Uchiyama, Kiyoshi (1910). Guide to Nanking. Shanghai: China Commercial Press.

- Wakeman, Frederic, Jr. (1985), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04804-0

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - Wang, Nengwei (1998). Nanjing Jiu Ying (Old Photos of Nanjing). Nanjing: People's Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Ye, Zhaoyan (1998). Lao Nanjing: Jiu Ying Qinhuai (Old Nanjing: Reflections of Scenes on the Qinhuai River). Nanjing: Zhongguo Di Er Lishi Dang An Guan (China Second National Archives).

- Yang, Xinhua; Lu, Haiming (2001). Nanjing Ming-Qing Jianzhu (Ming and Qing architecture of Nanjing). Nanjing Daxue Chubanshe (Nanjing University Press). ISBN 7-305-03669-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

Nanjing travel guide from Wikivoyage

Nanjing travel guide from Wikivoyage- Template:Zh icon Nanjing Government website

- Nanjing English guide with open directory

- NanjingExpat.com: Nanjing's largest English news network with city guide and classifieds

- HelloNanjing.net: Nanjing's most active social news and event network for foreigners

- List of Nanjing Government Departments

- Historic US Army map of Nanjing, 1945

- "Nanking Illustrated" from 1624