Orbit of the Moon: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 121.72.89.78 (talk) to last revision by RagingR2. (TW) |

m →Lunar periods: WP:CHECKWIKI error fixes using AWB (10469) |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

There are several different periods associated with the lunar orbit. |

There are several different periods associated with the lunar orbit.<ref>The periods are calculated from orbital elements, using the rate of change of quantities at the instant J2000. The J2000 rate of change equals the coefficient of the first-degree term of VSOP polynomials. In the original VSOP87 elements the units are arcseconds(”) and Julian centuries. There are 1,296,000” in a circle, 36525 days in a Julian century. The sidereal month is the time of a revolution of longitude λ with respect to the fixed J2000 equinox. VSOP87 gives 1732559343.7306” or 1336.8513455 revolutions in 36525 days–27.321661547 days per revolution. The tropical month is similar, but the longitude for the equinox of date is used. For the anomalistic year the mean anomaly (λ-ω) is used (equinox does not matter). For the draconic month (λ-Ω) is used. For the synodic month, the sidereal period of the mean Sun(or Earth) and the Moon. The period would be 1/(1/m-1/e). VSOP elements from {{cite journal |

||

|title = Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets |

|title = Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets |

||

|journal=Astronomy and Astrophysics |

|journal=Astronomy and Astrophysics |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

|last6=Laskar | first6=J. |

|last6=Laskar | first6=J. |

||

|bibcode=1994A&A...282..663S |

|bibcode=1994A&A...282..663S |

||

}}</ref>The [[Lunar month#Sidereal month|sidereal month]] is the time it takes to make one complete orbit of the earth with respect to the fixed stars, it is about 27.32 days. The [[Lunar month#Synodic month|synodic month]] is the time it takes the Moon to reach the same visual [[lunar phase|phase]]. This varies notably throughout the year, |

}}</ref> The [[Lunar month#Sidereal month|sidereal month]] is the time it takes to make one complete orbit of the earth with respect to the fixed stars, it is about 27.32 days. The [[Lunar month#Synodic month|synodic month]] is the time it takes the Moon to reach the same visual [[lunar phase|phase]]. This varies notably throughout the year,<ref name=AA>Jean Meeus, ''Astronomical Algorithms'' (Richmond, VA: Willmann-Bell, 1998) p 354. From 1900-2100 the shortest time from one new moon to the next is 29 days, 6 hours, and 35 min, and the longest 29 days, 19 hours, and 55 min.</ref> but averages around 29.53 days. The synodic period is longer than the sidereal period because the Earth–Moon system moves in its orbit around the [[Sun]] during each sidereal month, hence a longer period is required to achieve a similar alignment of the earth, sun and moon. The [[Lunar month#Anomalistic month|anomalistic month]] is the time between perigees and is about 27.55 days. The earth-moon separation determines the strength of the lunar tide raising force. |

||

The [[Lunar month#Draconic month|draconic month]] is the time from [[Orbital node|ascending node]] to ascending node. The time between two successive passes of the same ecliptic longitude is called the [[Lunar month#Tropical month|tropical month]]. The latter three periods are slightly different from the sidereal month. |

The [[Lunar month#Draconic month|draconic month]] is the time from [[Orbital node|ascending node]] to ascending node. The time between two successive passes of the same ecliptic longitude is called the [[Lunar month#Tropical month|tropical month]]. The latter three periods are slightly different from the sidereal month. |

||

Revision as of 22:49, 19 September 2014

- Not to be confused with Lunar orbit in the sense of a selenocentric orbit, that is, an orbit around the Moon

The Moon completes its orbit around the Earth in approximately 27.32 days (a sidereal month). The Earth and Moon orbit about their barycentre (common centre of mass), which lies about 4600 km from Earth's centre (about three quarters of the Earth's radius). On average, the Moon is at a distance of about 385000 km from the centre of the Earth, which corresponds to about 60 Earth radii. With a mean orbital velocity of 1.023 km/s,[1] the Moon moves relative to the stars each hour by an amount roughly equal to its angular diameter, or by about 0.5°. The Moon differs from most satellites of other planets in that its orbit is close to the plane of the ecliptic, and not to the Earth's equatorial plane. The lunar orbit plane is inclined to the ecliptic by about 5.1°, whereas the Moon's spin axis is inclined by only 1.5°.

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Semi-major axis[2] | 384748 km[3] |

| mean distance[4] | 385000 km[5] |

| inverse sine parallax[6] | 384400 km |

| Distance at perigee | ~362600 km (356400–370400 km) |

| Distance at apogee | ~405400 km (404000–406700 km) |

| Mean eccentricity | 0.0549006 (0.026–0.077)[7] |

| Mean inclination of orbit to ecliptic | 5.14° (4.99–5.30)[7] |

| Mean obliquity | 6.58° |

| Mean inclination of lunar equator to ecliptic | 1.543° |

| Period of precession of nodes | 18.5996 years |

| Period of recession of line of apsides | 8.8504 years |

Properties

The properties of the orbit described in this section are approximations. The Moon's orbit around the Earth has many irregularities (perturbations), whose study (lunar theory) has a long history.[8]

Elliptic shape

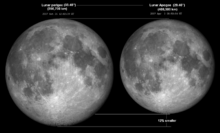

The orbit of the Moon is distinctly elliptical, with an average eccentricity of 0.0549. The non-circular form of the lunar orbit causes variations in the Moon's angular speed and apparent size as it moves towards and away from an observer on Earth. The mean angular movement relative to an imaginary observer at the barycentre is 13.176° to the east (Julian Day 2000.0 rate).

Line of apsides

The orientation of the orbit is not fixed in space, but precesses over time. The nearest and farthest points in the orbit are the perigee and apogee respectively. The line joining these two points (the line of apsides) rotates slowly in the same direction as the Moon itself (direct motion), making one complete revolution in 3232.6054 days or about 8.85 earth years.

Elongation

The Moon's elongation is its angular distance east of the Sun at any time. At new moon, it is zero and the Moon is said to be in conjunction. At full moon, the elongation is 180° and it is said to be in opposition. In both cases, the Moon is in syzygy, that is, the Sun, Moon and Earth are nearly aligned. When elongation is either 90° or 270° the Moon is said to be in quadrature.

Inclination

The mean inclination of the lunar orbit to the ecliptic plane is 5.145°. The rotation axis of the Moon is also not perpendicular to its orbital plane, so the lunar equator is not in the plane of its orbit, but is inclined to it by a constant value of 6.688° (this is the obliquity). One might be tempted to think that, as a result of the precession of the Moon's orbital plane, the angle between the lunar equator and the ecliptic would vary between the sum (11.833°) and difference (1.543°) of these two angles. However, as was discovered by Jacques Cassini in 1722, the rotation axis of the Moon precesses with the same rate as its orbital plane, but is 180° out of phase (see Cassini's Laws). Thus, although the rotation axis of the Moon is not fixed with respect to the stars, the angle between the ecliptic and the lunar equator is always 1.543°.

Nodes

The nodes are points at which the Moon's orbit crosses the ecliptic. The Moon crosses the same node every 27.2122 days, an interval called the draconic or draconitic month. The line of nodes, the intersection between the two respective planes, has a retrograde motion: for an observer on Earth it rotates westward along the ecliptic with a period of 18.60 years, or 19.3549° per year. When viewed from celestial north, the nodes move clockwise around the Earth, opposite the Earth's own spin and its revolution around the Sun. Lunar and solar eclipses can occur when the nodes align with the Sun, roughly every 173.3 days. Lunar orbit inclination also determines eclipses; shadows cross when nodes coincide with full and new moon, when the sun, earth, and moon align in three dimensions.

Lunar standstill

During a particular June solstice every 18.6 years the ecliptic reaches the highest declination in the southern hemisphere, −70°-130'. When at that time the ascending node has a 90° angle with the Sun in the southern hemisphere, the declination of the full Moon in the sky reaches a maximum at −23°29′ – 5°9′ or −28°36′. This is called the major standstill or lunistice in the southern hemisphere. 9.3 years later, when the descending node has a 90° angle with the December solstice, the declination of the full Moon in the sky reaches a maximum at 23°29′ + 5°9′ or 28°36′. The other major standstill or lunistice, this time in the northern hemisphere.

History of observations and measurements

About 3,000 years ago, the Babylonians were the first human civilization to keep a consistent record of lunar observations. Clay tablets from that period, which have been found over the territory of present-day Iraq, are inscribed with cuneiform writing recording the times and dates of moonrises and moonsets, the stars that the Moon passed close by, and the time differences between rising and setting of both the Sun and the Moon around the time of the full moon. Babylonian astronomy discovered the three main periods of the Moon's motion and used data analysis to build lunar calendars that extended well into the future.[8] This use of detailed, systematic observations to make predictions based on experimental data may be classified as the first scientific study in human history. However, the Babylonians seem to have lacked any geometrical or physical interpretation of their data, and they could not predict future lunar eclipses (although "warnings" were issued before likely eclipse times).

Ancient Greek astronomers were the first to introduce and analyze mathematical models of the motion of objects in the sky. Ptolemy described lunar motion by using a well-defined geometric model of epicycles and evection.[8]

Isaac Newton was the first to develop a complete theory of motion, mechanics. The sheer wealth of humanity's observations of the lunar motion was the main testbed of his theory.[8]

Lunar periods

| Name | Value (days) | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| sidereal month | 27.321662 | with respect to the distant stars (13.36874634 passes per solar orbit) |

| synodic month | 29.530589 | with respect to the Sun (phases of the Moon, 12.36874634 passes per solar orbit) |

| tropical month | 27.321582 | with respect to the vernal point (precesses in ~26,000 years) |

| anomalistic month | 27.554550 | with respect to the perigee (recesses in 3232.6054 days = 8.850578years) |

| draconic (nodical) month | 27.212221 | with respect to the ascending node (precesses in 6793.4765 days = 18.5996 years) |

There are several different periods associated with the lunar orbit.[9] The sidereal month is the time it takes to make one complete orbit of the earth with respect to the fixed stars, it is about 27.32 days. The synodic month is the time it takes the Moon to reach the same visual phase. This varies notably throughout the year,[10] but averages around 29.53 days. The synodic period is longer than the sidereal period because the Earth–Moon system moves in its orbit around the Sun during each sidereal month, hence a longer period is required to achieve a similar alignment of the earth, sun and moon. The anomalistic month is the time between perigees and is about 27.55 days. The earth-moon separation determines the strength of the lunar tide raising force.

The draconic month is the time from ascending node to ascending node. The time between two successive passes of the same ecliptic longitude is called the tropical month. The latter three periods are slightly different from the sidereal month.

The average length of a calendar month (a twelfth of a year) is about 30.4 days. This is not a lunar period, though the calendar month is historically related to the visible lunar phase.

Moon phases: 0 (1)—new moon, 0.25—first quarter, 0.5—full moon, 0.75—last quarter

Tidal evolution

The gravitational attraction that the Moon exerts on Earth is the major cause of tides in the sea; the Sun has a lesser tidal influence. If the Earth possessed a global ocean of uniform depth, the Moon would act to deform both the solid earth (by a small amount) and the ocean in the shape of an ellipsoid with high points roughly beneath the Moon and on the opposite side of the Earth. However, because of the presence of the continents, the much faster rotation of the earth and varying ocean depths, this simplistic visualisation does not happen. While the tidal flow period is generally synchronized to the Moon's orbit around Earth, its relative timing varies greatly. In some places on Earth, there is only one high tide per day while others have four, though this is somewhat rare.

The notional tidal bulges are carried ahead of the Earth–Moon axis by the continents as a result of the Earth's rotation. The eccentric mass of each bulge exerts a small amount of gravitational attraction on the Moon, with the bulge on the side of the Earth closest to the Moon pulling in a direction slightly forward along the Moon's orbit (because the Earth's rotation has carried the bulge forward). The bulge on the side furthest from the Moon has the opposite effect, but because the gravitational attraction varies inversely with the square of distance, the effect is stronger for the near-side bulge. As a result, some of the Earth's angular (or rotational) momentum is gradually being transferred to the rotation of the Earth-Moon couple about their mutual centre of mass, called the barycentre. This slightly faster rotation causes the Earth-Moon distance to increase at approximately 38 millimetres per year. In keeping with the conservation of angular momentum, the Earth's axial rotation is gradually slowing, and the Earth's day thus lengthens by about 23 microseconds every year (excluding glacial rebound). Both figures are valid only for the current configuration of the continents. Tidal rhythmites from 620 million years ago show that, over hundreds of millions of years, the Moon receded at an average rate of 22 millimetres per year and the day lengthened at an average rate of 12 microseconds per year, both about half of their current values. See tidal acceleration for a more detailed description and references.

The Moon is gradually receding from the Earth into a higher orbit, and calculations[11][12] suggest that this would continue for about fifty billion years. By that time, the Earth and Moon would become caught up in what is called a "spin–orbit resonance" or "tidal locking" in which the Moon will circle the Earth in about 47 days (currently 27 days), and both Moon and Earth would rotate around their axes in the same time, always facing each other with the same side. (This has already happened to the Moon—the same side always faces Earth. This is slowly happening to the Earth as well.) However, the slowdown of the Earth's rotation is not occurring fast enough for the rotation to lengthen to a month before other effects change the situation: about 2.3 billion years from now, the increase of the Sun's radiation will have caused the Earth's oceans to vaporize,[13] removing the bulk of the tidal friction and acceleration.

Libration

The Moon is in synchronous rotation, meaning that it keeps the same face turned toward the Earth at all times. This synchronous rotation is only true on average, because the Moon's orbit has a definite eccentricity. As a result, the angular velocity of the Moon varies as it moves around the Earth and hence is not always equal to the Moon's rotational velocity. When the Moon is at its perigee, its rotation is slower than its orbital motion, and this allows us to see up to eight degrees of longitude of its eastern (right) far side. Conversely, when the Moon reaches its apogee, its rotation is faster than its orbital motion and this reveals eight degrees of longitude of its western (left) far side. This is referred to as longitudinal libration.

Because the lunar orbit is also inclined to the Earth's ecliptic plane by 5.1°, the rotation axis of the Moon seems to rotate towards and away from us during one complete orbit. This is referred to as latitudinal libration, which allows one to see almost 7° of latitude beyond the pole on the far side. Finally, because the Moon is only about 60 Earth radii away from the Earth's centre of mass, an observer at the equator who observes the Moon throughout the night moves laterally by one Earth diameter. This gives rise to a diurnal libration, which allows one to view an additional one degree's worth of lunar longitude. For the same reason, observers at both geographical poles of the Earth would be able to see one additional degree's worth of libration in latitude.

Path of Earth and Moon around Sun

When viewed from the north celestial pole, i.e. from the star Polaris, the Moon orbits the Earth anticlockwise, the Earth orbits the Sun anticlockwise, and the Moon and Earth rotate on their own axes anticlockwise.

The right-hand rule can be used to indicate the direction of the angular velocity. If the thumb of the right hand points to the north celestial pole, its fingers curl in the direction that the Moon orbits the Earth, the Earth orbits the Sun, and the direction the Moon and Earth rotate on their own axes.

In representations of the Solar System, it is common to draw the trajectory of the Earth from the point of view of the Sun, and the trajectory of the Moon from the point of view of the Earth. This could give the impression that the Moon circles around the Earth in such a way that sometimes it goes backwards when viewed from the Sun's perspective. Since the orbital velocity of the Moon about the Earth (1 km/s) is small compared to the orbital velocity of the Earth about the Sun (30 km/s), this never occurs. There are no rearward loops in the Moon's solar orbit.

Considering the Earth–Moon system as a binary planet, its centre of gravity is within the Earth, about 4,624 km from its centre or 72.6% of its radius. This centre of gravity remains in-line towards the Moon as the Earth completes its diurnal rotation. It is this mutual centre of gravity that defines the path of the Earth–Moon system in solar orbit. Consequently the Earth's centre veers inside and outside the orbital path during each synodic month as the Moon moves in the opposite direction.[15]

Unlike most moons in the Solar System, the trajectory of the Moon around the Sun is very similar to that of Earth. The Sun's gravitational effect on the Moon is more than twice that of the Earth's on the Moon; consequently, the Moon's trajectory is always convex[15][16] (as seen when looking Sunward at the entire Sun–Earth–Moon system from a great distance outside the Earth/Moon solar orbit), and is nowhere concave (from the same perspective) or looped.[14][15][17]

See also

|

|

References

- ^ "Moon Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 2014-01-08.

- ^ The geometric mean distance in the orbit (of ELP)

- ^ M. Chapront-Touzé, J. Chapront (1983). "The lunar ephemeris ELP-2000". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 124: 54. Bibcode:1983A&A...124...50C.

- ^ The constant in the ELP expressions for the distance, which is the mean distance averaged over time

- ^ M. Chapront-Touzé, J. Chapront (1988). "ELP2000-85: a semi-analytical lunar ephemeris adequate for historical times". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 190: 351. Bibcode:1988A&A...190..342C.

- ^ This often quoted value for the mean distance is actually the inverse of the mean of the inverse of the distance, which is not the same as the mean distance itself.

- ^ a b Jean Meeus, Mathematical astronomy morsels (Richmond, VA: Willmann-Bell, 1997) 11–12.

- ^ a b c d Martin C. Gutzwiller (1998). "Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem". Reviews of Modern Physics. 70 (2): 589–639. Bibcode:1998RvMP...70..589G. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.70.589.

- ^ The periods are calculated from orbital elements, using the rate of change of quantities at the instant J2000. The J2000 rate of change equals the coefficient of the first-degree term of VSOP polynomials. In the original VSOP87 elements the units are arcseconds(”) and Julian centuries. There are 1,296,000” in a circle, 36525 days in a Julian century. The sidereal month is the time of a revolution of longitude λ with respect to the fixed J2000 equinox. VSOP87 gives 1732559343.7306” or 1336.8513455 revolutions in 36525 days–27.321661547 days per revolution. The tropical month is similar, but the longitude for the equinox of date is used. For the anomalistic year the mean anomaly (λ-ω) is used (equinox does not matter). For the draconic month (λ-Ω) is used. For the synodic month, the sidereal period of the mean Sun(or Earth) and the Moon. The period would be 1/(1/m-1/e). VSOP elements from Simon, J.L.; Bretagnon, P.; Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G.; Laskar, J. (February 1994). "Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282 (2): 669. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..663S.

- ^ Jean Meeus, Astronomical Algorithms (Richmond, VA: Willmann-Bell, 1998) p 354. From 1900-2100 the shortest time from one new moon to the next is 29 days, 6 hours, and 35 min, and the longest 29 days, 19 hours, and 55 min.

- ^ C.D. Murray; S.F. Dermott (1999). Solar System Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 184.

- ^ Dickinson, Terence (1993). From the Big Bang to Planet X. Camden East, Ontario: Camden House. pp. 79–81. ISBN 0-921820-71-2.

- ^ Caltech Scientists Predict Greater Longevity for Planets with Life

- ^ a b The reference by H L Vacher (2001)(details separately cited in this list) describes this as 'convex outward', while older references such as "The Moon's Orbit Around the Sun, Turner, A. B. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 6, p.117, 1912JRASC...6..117T"; and "H Godfray, Elementary Treatise on the Lunar Theory" describe the same geometry by the words concave to the sun.

- ^ a b c Aslaksen, Helmer (2010). "The Orbit of the Moon around the Sun is Convex!". Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ The Moon Always Veers Toward the Sun at MathPages

- ^ Vacher, H.L. (November 2001). "Computational Geology 18 – Definition and the Concept of Set" (PDF). Journal of Geoscience Education. 49 (5): 470–479. Retrieved 2006-04-21.