Green fluorescent protein: Difference between revisions

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

In fact, it is from the coherent scattering from perdeuterated GFP that has shown collective motions of adjacent chains in the beta barrel at ~1 THz.<ref>Nickels JD, Perticaroli S, O’Neill H, Zhang Q, Ehlers G, Sokolov AP. Coherent Neutron Scattering and Collective Dynamics in the Protein, GFP. Biophysical journal 2013;105:2182-2187</ref> These motions are thought to be sensitive to local rigidity within proteins, revealing beta structures to be generically more rigid than alpha or disordered proteins<ref>Perticaroli S, Nickels JD, Ehlers G, O'Neill H, Zhang Q, Sokolov AP. Secondary structure and rigidity in model proteins. Soft Matter 2013;9:9548-9556</ref><ref>Perticaroli S, Nickels JD, Ehlers G, Sokolov AP. Rigidity, secondary structure, and the Universality of the Boson Peak in Proteins. Biophysical journal 2014;106:2667-2674</ref>. |

In fact, it is from the coherent scattering from perdeuterated GFP that has shown collective motions of adjacent chains in the beta barrel at ~1 THz.<ref>Nickels JD, Perticaroli S, O’Neill H, Zhang Q, Ehlers G, Sokolov AP. Coherent Neutron Scattering and Collective Dynamics in the Protein, GFP. Biophysical journal 2013;105:2182-2187</ref> These motions are thought to be sensitive to local rigidity within proteins, revealing beta structures to be generically more rigid than alpha or disordered proteins<ref>Perticaroli S, Nickels JD, Ehlers G, O'Neill H, Zhang Q, Sokolov AP. Secondary structure and rigidity in model proteins. Soft Matter 2013;9:9548-9556</ref><ref>Perticaroli S, Nickels JD, Ehlers G, Sokolov AP. Rigidity, secondary structure, and the Universality of the Boson Peak in Proteins. Biophysical journal 2014;106:2667-2674</ref>. |

||

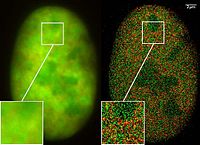

[[Image:GFP Contrast Scheme.jpg|Incoherent neutron scattering reveals dynamics from different parts of a protein based on the location of hydrogen in the system. Here we see on the left how a scattering experiment sees hydrogenated GFP in D2O (heavy water), and on the right, how the same experiment would see deuterated GFP in H2O (water).]] |

[[Image:GFP Contrast Scheme.jpg||thumb|200px|Incoherent neutron scattering reveals dynamics from different parts of a protein based on the location of hydrogen in the system. Here we see on the left how a scattering experiment sees hydrogenated GFP in D2O (heavy water), and on the right, how the same experiment would see deuterated GFP in H2O (water).]] |

||

==Applications== |

==Applications== |

||

Revision as of 18:51, 20 February 2015

| Green fluorescent protein | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein.[1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Reginal | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01353 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0069 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR011584 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1ema / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The green fluorescent protein (GFP) is a protein composed of 238 amino acid residues (26.9 kDa) that exhibits bright green fluorescence when exposed to light in the blue to ultraviolet range.[2][3] Although many other marine organisms have similar green fluorescent proteins, GFP traditionally refers to the protein first isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria. The GFP from A. victoria has a major excitation peak at a wavelength of 395 nm and a minor one at 475 nm. Its emission peak is at 509 nm, which is in the lower green portion of the visible spectrum. The fluorescence quantum yield (QY) of GFP is 0.79. The GFP from the sea pansy (Renilla reniformis) has a single major excitation peak at 498 nm.

In cell and molecular biology, the GFP gene is frequently used as a reporter of expression.[4] In modified forms it has been used to make biosensors, and many animals have been created that express GFP as a proof-of-concept that a gene can be expressed throughout a given organism. The GFP gene can be introduced into organisms and maintained in their genome through breeding, injection with a viral vector, or cell transformation. To date, the GFP gene has been introduced and expressed in many Bacteria, Yeast and other Fungi, fish (such as zebrafish), plant, fly, and mammalian cells, including human. Martin Chalfie, Osamu Shimomura, and Roger Y. Tsien were awarded the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry on 10 October 2008 for their discovery and development of the green fluorescent protein.

History

Wild-type GFP (wtGFP)

In the 1960s and 1970s, GFP, along with the separate luminescent protein aequorin (an enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of luciferin, releasing light), was first purified from Aequorea victoria and its properties studied by Osamu Shimomura.[5] In A. victoria, GFP fluorescence occurs when aequorin interacts with Ca2+ ions, inducing a blue glow. Some of this luminescent energy is transferred to the GFP, shifting the overall color towards green.[6] However, its utility as a tool for molecular biologists did not begin to be realized until 1992 when Douglas Prasher reported the cloning and nucleotide sequence of wtGFP in Gene.[7] The funding for this project had run out, so Prasher sent cDNA samples to several labs. The lab of Martin Chalfie expressed the coding sequence of wtGFP, with the first few amino acids deleted, in heterologous cells of E. coli and C. elegans, publishing the results in Science in 1994.[8] Frederick Tsuji's lab independently reported the expression of the recombinant protein one month later.[9] Remarkably, the GFP molecule folded and was fluorescent at room temperature, without the need for exogenous cofactors specific to the jellyfish. Although this near-wtGFP was fluorescent, it had several drawbacks, including dual peaked excitation spectra, pH sensitivity, chloride sensitivity, poor fluorescence quantum yield, poor photostability and poor folding at 37 °C.

The first reported crystal structure of a GFP was that of the S65T mutant by the Remington group in Science in 1996.[10] One month later, the Phillips group independently reported the wild-type GFP structure in Nature Biotech.[11] These crystal structures provided vital background on chromophore formation and neighboring residue interactions. Researchers have modified these residues by directed and random mutagenesis to produce the wide variety of GFP derivatives in use today. Martin Chalfie, Osamu Shimomura and Roger Y. Tsien share the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their discovery and development of the green fluorescent protein.[12]

GFP derivatives

Due to the potential for widespread usage and the evolving needs of researchers, many different mutants of GFP have been engineered.[13] The first major improvement was a single point mutation (S65T) reported in 1995 in Nature by Roger Tsien.[14] This mutation dramatically improved the spectral characteristics of GFP, resulting in increased fluorescence, photostability, and a shift of the major excitation peak to 488 nm, with the peak emission kept at 509 nm. This matched the spectral characteristics of commonly available FITC filter sets, increasing the practicality of use by the general researcher. A 37 °C folding efficiency (F64L) point mutant to this scaffold yielding enhanced GFP (EGFP) was discovered in 1995 by the laboratories of Thastrup[15] and Falkow.[16] EGFP allowed the practical use of GFPs in mammalian cells. EGFP has an extinction coefficient (denoted ε) of 55,000 M−1cm−1.[17] The fluorescence quantum yield (QY) of EGFP is 0.60. The relative brightness, expressed as ε•QY, is 33,000 M−1cm−1. Superfolder GFP, a series of mutations that allow GFP to rapidly fold and mature even when fused to poorly folding peptides, was reported in 2006.[18]

Many other mutations have been made, including color mutants; in particular, blue fluorescent protein (EBFP, EBFP2, Azurite, mKalama1), cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP, Cerulean, CyPet, mTurquoise2), and yellow fluorescent protein derivatives (YFP, Citrine, Venus, YPet). BFP derivatives (except mKalama1) contain the Y66H substitution.They exhibit a broad absorption band in the ultraviolet centered close to 380 nanometers and an emission maximum at 448 nanometers. A green fluorescent protein mutant (BFPms1) that preferentially binds Zn(II) and Cu(II) has been developed. BFPms1 have several important mutations including and the BFP chromophore (Y66H),Y145F for higher quantum yield, H148G for creating a hole into the beta-barrel and several other mutations that increase solubility. Zn(II) binding increases fluorescence intensity, while Cu(II) binding quenches fluorescence and shifts the absorbance maximum from 379 to 444 nm. Therefore they can be used as Zn biosensor.[19]

The critical mutation in cyan derivatives is the Y66W substitution, which causes the chromophore to form with an indole rather than phenol component. Several additional compensatory mutations in the surrounding barrel are required to restore brightness to this modified chromophore due to the increased bulk of the indole group. In ECFP and Cerulean, the N-terminal half of the seventh strand exhibits two conformations. These conformations both have a complex set of van der Waals interactions with the chromophore. The Y145A and H148D mutations in Cerulean stabilize these interactions and allow the chromophore to be more planar, better packed, and less prone to collisional quenching.[20] Additional site-directed random mutagenesis in combination with fluorescence lifetime based screening has further stabilized the seventh β-strand resulting in a bright variant, mTurquoise2, with a quantum yield (QY) of 0.93.[21] The red-shifted wavelength of the YFP derivatives is accomplished by the T203Y mutation and is due to π-electron stacking interactions between the substituted tyrosine residue and the chromophore.[3] These two classes of spectral variants are often employed for Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments.[22] Genetically encoded FRET reporters sensitive to cell signaling molecules, such as calcium or glutamate, protein phosphorylation state, protein complementation, receptor dimerization, and other processes provide highly specific optical readouts of cell activity in real time.

Semirational mutagenesis of a number of residues led to pH-sensitive mutants known as pHluorins, and later super-ecliptic pHluorins. By exploiting the rapid change in pH upon synaptic vesicle fusion, pHluorins tagged to synaptobrevin have been used to visualize synaptic activity in neurons.[23]

Redox sensitive versions of GFP (roGFP) were engineered by introduction of cysteines into the beta barrel structure. The redox state of the cysteines determines the fluorescent properties of roGFP.[24]

The nomenclature of modified GFPs is often confusing due to overlapping mapping of several GFP versions onto a single name. For example, mGFP often refers to a GFP with an N-terminal palmitoylation that causes the GFP to bind to cell membranes. However, the same term is also used to refer to monomeric GFP, which is often achieved by the dimer interface breaking A206K mutation.[25] Wild-type GFP has a weak dimerization tendency at concentrations above 5 mg/mL. mGFP also stands for "modified GFP," which has been optimized through amino acid exchange for stable expression in plant cells.

GFP in nature

The purpose of both the (primary) bioluminescence (from aequorin's action on luciferin) and the (secondary) fluorescence of GFP in jellyfish is unknown. GFP is co-expressed with aequorin in small granules around the rim of the jellyfish bell. The secondary excitation peak (480 nm) of GFP does absorb some of the blue emission of aequorin, giving the bioluminescence a more green hue. The serine 65 residue of the GFP chromophore is responsible for the dual-peaked excitation spectra of wild-type GFP. It is conserved in all three GFP isoforms originally cloned by Prasher. Nearly all mutations of this residue consolidate the excitation spectra to a single peak at either 395 nm or 480 nm. The precise mechanism of this sensitivity is complex, but, it seems, involves donation of a hydrogen from serine 65 to glutamate 222, which influences chromophore ionization.[3] Since a single mutation can dramatically enhance the 480 nm excitation peak, making GFP a much more efficient partner of aequorin, A. victoria appears to evolutionarily prefer the less-efficient, dual-peaked excitation spectrum. Roger Tsien has speculated that varying hydrostatic pressure with depth may affect serine 65's ability to donate a hydrogen to the chromophore and shift the ratio of the two excitation peaks. Thus, the jellyfish may change the color of its bioluminescence with depth. However, a collapse in the population of jellyfish in Friday Harbor, where GFP was originally discovered, has hampered further study of the role of GFP in the jellyfish's natural environment.

Other fluorescent proteins

Because of the great variety of engineered GFP derivatives, fluorescent proteins that belong to a different family, such as the bilirubin-inducible fluorescent protein UnaG, dsRed, eqFP611, Dronpa, TagRFPs, KFP, EosFP, Dendra, IrisFP and many others, are erroneously referred to as GFP derivatives. Several of these proteins display unique properties like red-shifted emission above 600 nm or photoconversion from a green-emitting state to a red-emitting state. These properties are so far unique to fluorescent proteins other than GFP derivatives.

Structure

GFP has a beta barrel structure consisting of eleven β-strands, with an alpha helix containing the covalently bonded chromophore 4-(p-hydroxybenzylidene)imidazolidin-5-one (HBI) running through the center.[3][10][11] Five shorter alpha helices form caps on the ends of the structure. The beta barrel structure is a nearly perfect cylinder, 42Å long and 24Å in diameter,[10] creating what is referred to as a “β-can” formation, which is unique to the GFP-like family.[11] HBI, the spontaneously modified form of the tripeptide Ser65–Tyr66–Gly67, is nonfluorescent in the absence of the properly folded GFP scaffold and exists mainly in the un-ionized phenol form in wtGFP.[26] Inward-facing sidechains of the barrel induce specific cyclization reactions in Ser65–Tyr66–Gly67 that induce ionization of HBI to the phenolate form and chromophore formation. This process of post-translational modification is referred to as maturation.[27] The hydrogen-bonding network and electron-stacking interactions with these sidechains influence the color, intensity and photostability of GFP and its numerous derivatives.[28] The tightly packed nature of the barrel excludes solvent molecules, protecting the chromophore fluorescence from quenching by water.

|

|

Dynamics

As discussed below in the Applications section, GFP can be inserted onto many genes and used to track large scale domain motions and time dependent co-localizations in proteins by means of FRET.

Ease of expression has also enabled GFP to act as a prototype for studies of protein and hydration water dynamics using neutron scattering[29]. This technique focuses on motions faster than ~1 nanosecond, and by expressing the protein in a perdeuterated state one can isolate the motions of hydration water from those of the protein. In fact, it is from the coherent scattering from perdeuterated GFP that has shown collective motions of adjacent chains in the beta barrel at ~1 THz.[30] These motions are thought to be sensitive to local rigidity within proteins, revealing beta structures to be generically more rigid than alpha or disordered proteins[31][32].

Applications

Fluorescence Microscopy

The availability of GFP and its derivatives has thoroughly redefined fluorescence microscopy and the way it is used in cell biology and other biological disciplines.[33] While most small fluorescent molecules such as FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) are strongly phototoxic when used in live cells, fluorescent proteins such as GFP are usually much less harmful when illuminated in living cells. This has triggered the development of highly automated live-cell fluorescence microscopy systems, which can be used to observe cells over time expressing one or more proteins tagged with fluorescent proteins. For example, GFP had been widely used in labelling the spermatozoa of various organisms for identification purposes as in Drosophila melanogaster, where expression of GFP can be used as a marker for a particular characteristic. GFP can also be expressed in different structures enabling morphological distinction. In such cases, the gene for the production of GFP is incorporated into the genome of the organism in the region of the DNA that codes for the target proteins and that is controlled by the same regulatory sequence; that is, the gene's regulatory sequence now controls the production of GFP, in addition to the tagged protein(s). In cells where the gene is expressed, and the tagged proteins are produced, GFP is produced at the same time. Thus, only those cells in which the tagged gene is expressed, or the target proteins are produced, will fluoresce when observed under fluorescence microscopy. Analysis of such time lapse movies has redefined the understanding of many biological processes including protein folding, protein transport, and RNA dynamics, which in the past had been studied using fixed (i.e., dead) material. Obtained data are also used to calibrate mathematical models of intracellular systems and to estimate rates of gene expression.[34]

The Vertico SMI microscope using the SPDM Phymod technology uses the so-called "reversible photobleaching" effect of fluorescent dyes like GFP and its derivatives to localize them as single molecules in an optical resolution of 10 nm. This can also be performed as a co-localization of two GFP derivatives (2CLM).[35]

Another powerful use of GFP is to express the protein in small sets of specific cells. This allows researchers to optically detect specific types of cells in vitro (in a dish), or even in vivo (in the living organism).[36] Genetically combining several spectral variants of GFP is a useful trick for the analysis of brain circuitry (Brainbow).[37] Other interesting uses of fluorescent proteins in the literature include using FPs as sensors of neuron membrane potential,[38] tracking of AMPA receptors on cell membranes,[39] viral entry and the infection of individual influenza viruses and lentiviral viruses,[40][41] etc.

It has also been found that new lines of transgenic GFP rats can be relevant for gene therapy as well as regenerative medicine.[42] By using "high-expresser" GFP, transgenic rats display high expression in most tissues, and many cells that have not been characterized or have been only poorly characterized in previous GFP-transgenic rats. Through its ability to form internal chromophore without requiring accessory cofactors, enzymes or substrates other than molecular oxygen, GFP makes for an excellent tool in all forms of biology.[43]

GFP has been shown to be useful in cryobiology as a viability assay. Correlation of viability as measured by trypan blue assays were 0.97.[44] Another application is the use of GFP co-transfection as internal control for transfection efficiency in mammalian cells.[45]

A novel possible use of GFP includes using it as a sensitive monitor of intracellular processes via an eGFP laser system made out of a human embryonic kidney cell line. The first engineered living laser is made by an eGFP expressing cell inside a reflective optical cavity and hitting it with pulses of blue light. At a certain pulse threshold, the eGFP’s optical output becomes brighter and completely uniform in color of pure green with a wavelength of 516 nm. Before being emitted as laser light, the light bounces back and forth within the resonator cavity and passes the cell numerous times. By studying the changes in optical activity, researchers may better understand cellular processes.[46][47]

GFP is used widely in cancer research to label and track cancer cells. GFP-labelled cancer cells have been used to model metastasis, the process by which cancer cells spread to distant organs.[48]

Transgenic pets

|

Alba, a green-fluorescent rabbit, was created by a French laboratory commissioned by Eduardo Kac using GFP for purposes of art and social commentary.[49] The US company Yorktown Technologies markets to aquarium shops green fluorescent zebrafish (GloFish) that were initially developed to detect pollution in waterways. NeonPets, a US-based company has marketed green fluorescent mice to the pet industry as NeonMice.[50] Green fluorescent pigs, known as Noels, were bred by a group of researchers led by Wu Shinn-Chih at the Department of Animal Science and Technology at National Taiwan University.[51] A Japanese-American Team created green-fluorescent cats as proof of concept to use them potentially as model organisms for diseases, particularly HIV.[52] In 2009 a South Korean team from Seoul National University bred the first transgenic beagles with fibroblast cells from sea anemones. The dogs give off a red fluorescent light, and they are meant to allow scientists to study the genes that cause human diseases like narcolepsy and blindness.[53]

GFP in fine art

Julian Voss-Andreae, a German-born artist specializing in "protein sculptures,"[54] created sculptures based on the structure of GFP, including the 1.70 m (5'6") tall "Green Fluorescent Protein" (2004)[55] and the 1.40 m (4'7") tall "Steel Jellyfish" (2006). The latter sculpture is located at the place of GFP's discovery by Shimomura in 1962, the University of Washington's Friday Harbor Laboratories.[56]

See also

- pGLO

- Yellow fluorescent protein

- Red fluorescent protein(called DsRed)

References

- ^ Ormö M, Cubitt AB, Kallio K, Gross LA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ; Cubitt; Kallio; Gross; Tsien; Remington (September 1996). "Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein". Science. 273 (5280): 1392–5. doi:10.1126/science.273.5280.1392. PMID 8703075.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prendergast FG, Mann KG; Mann (1978). "Chemical and physical properties of aequorin and the green fluorescent protein isolated from Aequorea forskålea". Biochemistry. 17 (17): 3448–53. doi:10.1021/bi00610a004. PMID 28749.

- ^ a b c d Tsien RY (1998). "The green fluorescent protein" (PDF). Annu Rev Biochem. 67: 509–44. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. PMID 9759496.

- ^ Phillips GJ (2001). "Green fluorescent protein--a bright idea for the study of bacterial protein localization". FEMS Microbiol Lett. 204 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(01)00358-5. PMID 11682170.

- ^ Shimomura O, Johnson FH, Saiga Y; Johnson; Saiga (1962). "Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea". J Cell Comp Physiol. 59 (3): 223–39. doi:10.1002/jcp.1030590302. PMID 13911999.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morise H, Shimomura O, Johnson FH, Winant J; Shimomura; Johnson; Winant (1974). "Intermolecular energy transfer in the bioluminescent system of Aequorea". Biochemistry. 13 (12): 2656–62. doi:10.1021/bi00709a028. PMID 4151620.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prasher DC, Eckenrode VK, Ward WW, Prendergast FG, Cormier MJ; Eckenrode; Ward; Prendergast; Cormier (1992). "Primary structure of the Aequorea victoria green-fluorescent protein". Gene. 111 (2): 229–33. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(92)90691-H. PMID 1347277.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC; Tu; Euskirchen; Ward; Prasher (1994). "Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression". Science. 263 (5148): 802–5. doi:10.1126/science.8303295. PMID 8303295.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Inouye S, Tsuji FI; Tsuji (1994). "Aequorea green fluorescent protein. Expression of the gene and fluorescence characteristics of the recombinant protein". FEBS Lett. 341 (2–3): 277–80. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)80472-9. PMID 8137953.

- ^ a b c Ormö M, Cubitt AB, Kallio K, Gross LA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ; Cubitt; Kallio; Gross; Tsien; Remington (1996). "Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein". Science. 273 (5280): 1392–5. doi:10.1126/science.273.5280.1392. PMID 8703075.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Yang F, Moss LG, Phillips GN; Moss; Phillips Jr (1996). "The molecular structure of green fluorescent protein". Nat Biotechnol. 14 (10): 1246–51. doi:10.1038/nbt1096-1246. PMID 9631087.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2008". 2008-10-08. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Shaner NC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY; Steinbach; Tsien (2005). "A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins" (PDF). Nat Methods. 2 (12): 905–9. doi:10.1038/nmeth819. PMID 16299475.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heim R, Cubitt AB, Tsien RY; Cubitt; Tsien (1995). "Improved green fluorescence" (PDF). Nature. 373 (6516): 663–4. doi:10.1038/373663b0. PMID 7854443.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ US patent 6172188, Thastrup O, Tullin S, Kongsbak Poulsen L, Bjørn S, "Fluorescent Proteins", published 2001-01-09

- ^ Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S; Valdivia; Falkow (1996). "FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP)". Gene. 173 (1): 33–38. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. PMID 8707053.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McRae SR, Brown CL, Bushell GR; Brown; Bushell (May 2005). "Rapid purification of EGFP, EYFP, and ECFP with high yield and purity". Protein Expression and Purification. 41 (1): 121–127. doi:10.1016/j.pep.2004.12.030. PMID 15802229.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pédelacq JD, Cabantous S, Tran T, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS; Cabantous; Tran; Terwilliger; Waldo (2006). "Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein". Nat Biotechnol. 24 (1): 79–88. doi:10.1038/nbt1172. PMID 16369541.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barondeau DP, Kassmann CJ, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED; Kassmann; Tainer; Getzoff (2002). "Structural Chemistry of a Green Fluorescent Protein Zn Biosensor". J Am Chem Soc. 124 (14): 3522–3524. doi:10.1021/ja0176954. PMID 11929238.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lelimousin M, Noirclerc-Savoye M, Lazareno-Saez C, Paetzold B, Le Vot S, Chazal R, Macheboeuf P, Field MJ, Bourgeois D, Royant A; Noirclerc-Savoye; Lazareno-Saez; Paetzold; Le Vot; Chazal; Macheboeuf; Field; Bourgeois; Royant (2009). "Intrinsic dynamics in ECFP and Cerulean control fluorescence quantum yield". Biochemistry. 48 (42): 10038–10046. doi:10.1021/bi901093w. PMID 19754158.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goedhart, J; von Stetten, D; Noirclerc-Savoye, M; Lelimousin, M; Joosen, L; Hink, MA; van Weeren, L; Gadella TW, Jr; Royant, A (2012). "Structure-guided evolution of cyan fluorescent proteins towards a quantum yield of 93%". Nature communications. 3: 751. doi:10.1038/ncomms1738. PMC 3316892. PMID 22434194.

- ^ Atanasov AG, Nashev LG, Gelman L, Legeza B, Sack R, Portmann R, Odermatt A; Nashev; Gelman; Legeza; Sack; Portmann; Odermatt (August 2008). "Direct protein-protein interaction of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in the endoplasmic reticulum lumen". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1783 (8): 1536–43. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.03.001. PMID 18381077.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Miesenböck G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE; De Angelis; Rothman (1998). "Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins". Nature. 394 (6689): 192–5. doi:10.1038/28190. PMID 9671304.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hanson GT, Aggeler R, Oglesbee D, Cannon M, Capaldi RA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ; Aggeler; Oglesbee; Cannon; Capaldi; Tsien; Remington (2004). "Investigating mitochondrial redox potential with redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein indicators". J Biol Chem. 279 (13): 13044–53. doi:10.1074/jbc.M312846200. PMID 14722062.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zacharias DA, Violin JD, Newton AC, Tsien RY; Violin; Newton; Tsien (2002). "Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells". Science. 296 (5569): 913–16. doi:10.1126/science.1068539. PMID 11988576.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bokman SH, Ward WW (1982). "Reversible denaturation of Aequorea green-fluorescent protein: physical separation and characterization of the renatured protein". Biochemistry. 21 (19): 4535–4540. doi:10.1021/bi00262a003.

- ^ Pouwels LJ, Zhang L, Chan NH, Dorrestein PC, Wachter RM; Zhang; Chan; Dorrestein; Wachter (September 2008). "Kinetic isotope effect studies on the de novo rate of chromophore formation in fast- and slow-maturing GFP variants". Biochemistry. 47 (38): 10111–22. doi:10.1021/bi8007164. PMC 2643082. PMID 18759496.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chudakov DM, Matz MV, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov KA; Matz; Lukyanov; Lukyanov (2010). "Fluorescent proteins and their applications in imaging living cells and tissues". Physiological Reviews. 90 (3): 1103–63. doi:10.1152/physrev.00038.2009. PMID 20664080.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nickels, Jonathan D., et al. "Dynamics of protein and its hydration water: neutron scattering studies on fully deuterated GFP." Biophysical journal 103.7 (2012): 1566-1575.

- ^ Nickels JD, Perticaroli S, O’Neill H, Zhang Q, Ehlers G, Sokolov AP. Coherent Neutron Scattering and Collective Dynamics in the Protein, GFP. Biophysical journal 2013;105:2182-2187

- ^ Perticaroli S, Nickels JD, Ehlers G, O'Neill H, Zhang Q, Sokolov AP. Secondary structure and rigidity in model proteins. Soft Matter 2013;9:9548-9556

- ^ Perticaroli S, Nickels JD, Ehlers G, Sokolov AP. Rigidity, secondary structure, and the Universality of the Boson Peak in Proteins. Biophysical journal 2014;106:2667-2674

- ^ Yuste R (2005). "Fluorescence microscopy today". Nat Methods. 2 (12): 902–4. doi:10.1038/nmeth1205-902. PMID 16299474.

- ^ Komorowski M, Finkenstädt B, Rand D; Finkenstädt; Rand (June 2010). "Using a Single Fluorescent Reporter Gene to Infer Half-Life of Extrinsic Noise and Other Parameters of Gene Expression". Biophys J. 98 (12): 2759–2769. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.032. PMC 2884236. PMID 20550887.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gunkel M, Erdel F, Rippe K, Lemmer P, Kaufmann R, Hörmann C, Amberger R, Cremer C; Erdel; Rippe; Lemmer; Kaufmann; Hörmann; Amberger; Cremer (June 2009). "Dual color localization microscopy of cellular nanostructures". Biotechnol J. 4 (6): 927–38. doi:10.1002/biot.200900005. PMID 19548231.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chudakov DM, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov KA; Lukyanov; Lukyanov (2005). "Fluorescent proteins as a toolkit for in vivo imaging". Trends Biotechnol. 23 (12): 605–13. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.10.005. PMID 16269193.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Livet J, Weissman TA, Kang H, Draft RW, Lu J, Bennis RA, Sanes JR, Lichtman JW; Weissman; Kang; Draft; Lu; Bennis; Sanes; Lichtman (November 2007). "Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system". Nature. 450 (7166): 56–62. doi:10.1038/nature06293. PMID 17972876.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baker BJ, Mutoh H, Dimitrov D, Akemann W, Perron A, Iwamoto Y, Jin L, Cohen LB, Isacoff EY, Pieribone VA, Hughes T, Knöpfel T; Mutoh; Dimitrov; Akemann; Perron; Iwamoto; Jin; Cohen; Isacoff; Pieribone; Hughes; Knöpfel (August 2008). "Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors of membrane potential". Brain Cell Biol. 36 (1–4): 53–67. doi:10.1007/s11068-008-9026-7. PMC 2775812. PMID 18679801.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Adesnik H, Nicoll RA, England PM; Nicoll; England (December 2005). "Photoinactivation of native AMPA receptors reveals their real-time trafficking". Neuron. 48 (6): 977–85. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.030. PMID 16364901.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lakadamyali M, Rust MJ, Babcock HP, Zhuang X; Rust; Babcock; Zhuang (August 2003). "Visualizing infection of individual influenza viruses". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (16): 9280–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832269100. PMC 170909. PMID 12883000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Joo KI, Wang P; Wang (October 2008). "Visualization of Targeted Transduction by Engineered Lentiviral Vectors". Gene Ther. 15 (20): 1384–96. doi:10.1038/gt.2008.87. PMC 2575058. PMID 18480844.

- ^ Remy S, Tesson L, Usal C, Menoret S, Bonnamain V, Nerriere-Daguin V, Rossignol J, Boyer C, Nguyen TH, Naveilhan P, Lescaudron L, Anegon I; Tesson; Usal; Menoret; Bonnamain; Nerriere-Daguin; Rossignol; Boyer; Nguyen; Naveilhan; Lescaudron; Anegon (January 2010). "New lines of GFP transgenic rats relevant for regenerative medicine and gene therapy". Transgenic Res. 19 (5): 745–63. doi:10.1007/s11248-009-9352-2. PMID 20094912.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stepanenko OV, Verkhusha VV, Kuznetsova IM, Uversky VN, Turoverov KK; Verkhusha; Kuznetsova; Uversky; Turoverov (August 2008). "Fluorescent Proteins as Biomarkers and Biosensors: Throwing Color Lights on Molecular and Cellular Processes". Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 9 (4): 338–69. doi:10.2174/138920308785132668. PMC 2904242. PMID 18691124.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elliott G, McGrath J, Crockett-Torabi E; McGrath; Crockett-Torabi (2000). "Green fluorescent protein: A novel viability assay for cryobiological applications". Cryobiology. 40 (4): 360–369. doi:10.1006/cryo.2000.2258. PMID 10924267.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fakhrudin N, Ladurner A, Atanasov AG, Heiss EH, Baumgartner L, Markt P, Schuster D, Ellmerer EP, Wolber G, Rollinger JM, Stuppner H, Dirsch VM; Ladurner; Atanasov; Heiss; Baumgartner; Markt; Schuster; Ellmerer; Wolber; Rollinger; Stuppner; Dirsch (April 2010). "Computer-aided discovery, validation, and mechanistic characterization of novel neolignan activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma". Mol. Pharmacol. 77 (4): 559–66. doi:10.1124/mol.109.062141. PMC 3523390. PMID 20064974.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gather MC, Yun SH; Yun (2011). "Single-cell biological lasers". Nature Photonics. 5 (7): 406. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2011.99.

- ^ Matson J (2011). "Green Fluorescent Protein Makes for Living Lasers". Scientific American. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ Kouros-Mehr H, Bechis SK, Slorach EM, Littlepage LE, Egeblad M, Ewald AJ, Pai SY, Ho IC, Werb Z; Bechis; Slorach; Littlepage; Egeblad; Ewald; Pai; Ho; Werb (Feb 2008). "GATA-3 links tumor differentiation and dissemination in a luminal breast cancer model". Cancer Cell. 13 (2): 141–52. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.011. PMC 2262951. PMID 18242514.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eduardo Kac. "GFP Bunny".

- ^ Archived 2012-05-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Scientists in Taiwan breed fluorescent green pigs

- ^ Wongsrikeao P, Saenz D, Rinkoski T, Otoi T, Poeschla E; Saenz; Rinkoski; Otoi; Poeschla (2011). "Antiviral restriction factor transgenesis in the domestic cat". Nature Methods. 8 (10): 853–9. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1703. PMC 4006694. PMID 21909101.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [1]

- ^ Voss-Andreae J (2005). "Protein Sculptures: Life's Building Blocks Inspire Art". Leonardo. 38: 41–45. doi:10.1162/leon.2005.38.1.41.

- ^ Pawlak A (2005). "Inspirierende Proteine". Physik Journal. 4: 12.

- ^ "Julian Voss-Andreae Sculpture". Retrieved 2007-06-14.

Further reading

- Pieribone V, Gruber D (2006). Aglow in the Dark: The Revolutionary Science of Biofluorescence. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-01921-0. OCLC 60321612. Popular science book describing history and discovery of GFP

- Zimmer M (2005). Glowing Genes: A Revolution In Biotechnology. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-253-3. OCLC 56614624.

External links

- GFP Antibodies

- Novus Biologicals: GFP Antibody

- A comprehensive article on fluorescent proteins at Scholarpedia

- Brief summary of landmark GFP papers

- Interactive Java applet demonstrating the chemistry behind the formation of the GFP chromophore

- Video of 2008 Nobel Prize lecture of Roger Tsien on fluorescent proteins

- Excitation and emission spectra for various fluorescent proteins

- Green Fluorescent Protein Chem Soc Rev themed issue dedicated to the 2008 Nobel Prize winners in Chemistry, Professors Osamu Shimomura, Martin Chalfie and Roger Y. Tsien

- Molecule of the Month, June 2003: an illustrated overview of GFP by David Goodsell.