Charon's obol: Difference between revisions

→Western Europe: clean up, replaced: Viking → Norsemen, Viking → Norsemen, replaced: Norsemen Age → Viking Age, Norsemen period, → Viking age using AWB |

Charon’s Obols |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==Terminology== |

==Terminology== |

||

{{multiple image |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| align = right |

|||

| width = 210 |

|||

| header = Charon’s Obols |

|||

| footer = |

|||

| image1 = Charon-obol2.jpg |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| caption1 = Charon’s Obol. 5th-1st century BC. All of these pseudo-coins have no sign of attachment, are too thin for normal use, and are often found in burial sites. |

|||

| image2 = Medusa coin.jpg |

|||

| alt2 = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

|||

The coin for Charon is conventionally referred to in Greek literature as an ''obolos'' ([[ancient Greek|Greek]] ὀβολός), one of the basic [[denomination (currency)|denominations]] of [[ancient Greek coinage]], worth one-sixth of a [[drachma]].<ref>Depending on whether a [[copper]] or [[silver standard]] was used; see Verne B. Schuman, “The Seven-[[Obolus|Obol]] [[Drachma]] of [[History of Roman Egypt|Roman Egypt]],” ''Classical Philology'' 47 (1952) 214–218; Michael Vickers, “Golden Greece: Relative Values, Minae, and Temple Inventories,” ''American Journal of Archaeology'' 94 (1990), p. 613, notes 4 and 6, pointing out at the time of writing that with gold at $368.75 per [[ounce]], an obol would be worth 59 [[cent (currency)|cents]] ([[United States dollar|U.S. currency]]).</ref> Among the Greeks, coins in actual burials are sometimes also a [[danake|danakē]] (δανάκη) or other relatively small-denomination [[gold]], [[silver]], [[bronze]] or [[copper]] coin in local use. In Roman literary sources the coin is usually [[Roman coinage|bronze or copper]].<ref>For instance, [[Propertius]] 4.11.7–8; [[Juvenal]] 3.267; [[Apuleius]], ''Metamorphoses'' 6.18; [[Ernest Babelon]], ''Traité des monnaies grecques et romaines'', vol. 1 (Paris: Leroux, 1901), p. 430.</ref> From the 6th to the 4th centuries BC in the [[Black Sea]] region, low-value coins depicting [[arrowhead]]s or [[dolphin]]s were in use mainly for the purpose of "local exchange and to serve as ‘Charon’s obol.‘”<ref>Sitta von Reden, “Money, Law and Exchange: Coinage in the Greek [[Polis]],” ''Journal of Hellenic Studies'' 117 (1997), p. 159.</ref> The payment is sometimes specified with a term for “boat fare” (in Greek ''naulon'', ναῦλον, Latin ''naulum''); “fee for ferrying” (''porthmeion'', πορθμήϊον or πορθμεῖον); or “waterway toll” (Latin ''portorium''). |

The coin for Charon is conventionally referred to in Greek literature as an ''obolos'' ([[ancient Greek|Greek]] ὀβολός), one of the basic [[denomination (currency)|denominations]] of [[ancient Greek coinage]], worth one-sixth of a [[drachma]].<ref>Depending on whether a [[copper]] or [[silver standard]] was used; see Verne B. Schuman, “The Seven-[[Obolus|Obol]] [[Drachma]] of [[History of Roman Egypt|Roman Egypt]],” ''Classical Philology'' 47 (1952) 214–218; Michael Vickers, “Golden Greece: Relative Values, Minae, and Temple Inventories,” ''American Journal of Archaeology'' 94 (1990), p. 613, notes 4 and 6, pointing out at the time of writing that with gold at $368.75 per [[ounce]], an obol would be worth 59 [[cent (currency)|cents]] ([[United States dollar|U.S. currency]]).</ref> Among the Greeks, coins in actual burials are sometimes also a [[danake|danakē]] (δανάκη) or other relatively small-denomination [[gold]], [[silver]], [[bronze]] or [[copper]] coin in local use. In Roman literary sources the coin is usually [[Roman coinage|bronze or copper]].<ref>For instance, [[Propertius]] 4.11.7–8; [[Juvenal]] 3.267; [[Apuleius]], ''Metamorphoses'' 6.18; [[Ernest Babelon]], ''Traité des monnaies grecques et romaines'', vol. 1 (Paris: Leroux, 1901), p. 430.</ref> From the 6th to the 4th centuries BC in the [[Black Sea]] region, low-value coins depicting [[arrowhead]]s or [[dolphin]]s were in use mainly for the purpose of "local exchange and to serve as ‘Charon’s obol.‘”<ref>Sitta von Reden, “Money, Law and Exchange: Coinage in the Greek [[Polis]],” ''Journal of Hellenic Studies'' 117 (1997), p. 159.</ref> The payment is sometimes specified with a term for “boat fare” (in Greek ''naulon'', ναῦλον, Latin ''naulum''); “fee for ferrying” (''porthmeion'', πορθμήϊον or πορθμεῖον); or “waterway toll” (Latin ''portorium''). |

||

Revision as of 01:30, 28 May 2015

Charon's obol is an allusive term for the coin placed in or on the mouth[1] of a dead person before burial. Greek and Latin literary sources specify the coin as an obol, and explain it as a payment or bribe for Charon, the ferryman who conveyed souls across the river that divided the world of the living from the world of the dead. Archaeological examples of these coins, of various denominations in practice, have been called "the most famous grave goods from antiquity."[2]

The custom is primarily associated with the ancient Greeks and Romans, though it is also found in the ancient Near East. In Western Europe, a similar usage of coins in burials occurs in regions inhabited by Celts of the Gallo-Roman, Hispano-Roman and Romano-British cultures, and among the Germanic peoples of late antiquity and the early Christian era, with sporadic examples into the early 20th century.

Although archaeology shows that the myth reflects an actual custom, the placement of coins with the dead was neither pervasive nor confined to a single coin in the deceased's mouth.[3] In many burials, inscribed metal-leaf tablets or exonumia take the place of the coin, or gold-foil crosses in the early Christian era. The presence of coins or a coin-hoard in Germanic ship-burials suggests an analogous concept.[4]

The phrase "Charon’s obol" as used by archaeologists sometimes can be understood as referring to a particular religious rite, but often serves as a kind of shorthand for coinage as grave goods presumed to further the deceased's passage into the afterlife.[5] In Latin, Charon's obol sometimes is called a viaticum, or "sustenance for the journey"; the placement of the coin on the mouth has been explained also as a seal to protect the deceased's soul or to prevent it from returning.

Terminology

The coin for Charon is conventionally referred to in Greek literature as an obolos (Greek ὀβολός), one of the basic denominations of ancient Greek coinage, worth one-sixth of a drachma.[7] Among the Greeks, coins in actual burials are sometimes also a danakē (δανάκη) or other relatively small-denomination gold, silver, bronze or copper coin in local use. In Roman literary sources the coin is usually bronze or copper.[8] From the 6th to the 4th centuries BC in the Black Sea region, low-value coins depicting arrowheads or dolphins were in use mainly for the purpose of "local exchange and to serve as ‘Charon’s obol.‘”[9] The payment is sometimes specified with a term for “boat fare” (in Greek naulon, ναῦλον, Latin naulum); “fee for ferrying” (porthmeion, πορθμήϊον or πορθμεῖον); or “waterway toll” (Latin portorium).

The word naulon (ναῦλον) is defined by the Christian-era lexicographer Hesychius of Alexandria as the coin put into the mouth of the dead; one of the meanings of danakē (δανάκη) is given as “the obol for the dead”. The Suda defines danakē as a coin traditionally buried with the dead for paying the ferryman to cross the river Acheron,[10] and explicates the definition of porthmēïon (πορθμήϊον) as a ferryman’s fee with a quotation from the poet Callimachus, who notes the custom of carrying the porthmēïon in the “parched mouths of the dead.”[11]

Charon's obol as viaticum

In Latin, Charon’s obol is sometimes called a viaticum,[12] which in everyday usage means “provision for a journey” (from via, “way, road, journey”), encompassing food, money and other supplies. The same word can refer to the living allowance granted to those stripped of their property and condemned to exile,[13] and by metaphorical extension to preparing for death at the end of life’s journey.[14] Cicero, in his philosophical dialogue On Old Age (44 BC), has the interlocutor Cato the Elder combine two metaphors — nearing the end of a journey, and ripening fruit — in speaking of the approach to death:

I don’t understand what greed should want for itself in old age; for can anything be sillier than to acquire more provisions (viaticum) as less of the journey remains?[15] … Fruits, if they are green, can scarcely be wrenched off the trees; if they are ripe and softened, they fall. In the same way, violence carries off the life of young men; old men, the fullness of time. To me this is so richly pleasing that, the nearer I draw to death, I seem within sight of landfall, as if, at an unscheduled time, I will come into the harbor after a long voyage.[16]

Drawing on this metaphorical sense of “provision for the journey into death,” ecclesiastical Latin borrowed the term viaticum for the form of Eucharist that is placed in the mouth of a person who is dying as provision for the soul’s passage to eternal life.[17] The earliest literary evidence of this Christian usage for viaticum appears in Paulinus’s account of the death of Saint Ambrose in 397 AD.[18] The 7th-century Synodus Hibernensis offers an etymological explanation: “This word ‘viaticum’ is the name of communion, that is to say, ‘the guardianship of the way,’ for it guards the soul until it shall stand before the judgment-seat of Christ.”[19] Thomas Aquinas explained the term as “a prefiguration of the fruit of God, which will be in the promised land. And because of this it is called the viaticum, since it provides us with the way of getting there”; the idea of Christians as “travelers in search of salvation” finds early expression in the Confessions of St. Augustine.[20]

An equivalent word in Greek is ephodion (ἐφόδιον); like viaticum, the word is used in antiquity to mean “provision for a journey” (literally, “something for the road,” from the prefix ἐπ-, “on” + ὁδός, “road, way”)[21] and later in Greek patristic literature for the Eucharist administered on the point of death.[22]

In literature

Greek and Roman literary sources from the 5th century BC through the 2nd century AD are consistent in attributing four characteristics to Charon’s obol:

- it is a single, low-denomination coin;

- it is placed in the mouth;

- the placement occurs at the time of death;

- it represents a boat fare.[24]

Greek epigrams that were literary versions of epitaphs refer to “the obol that pays the passage of the departed,”[25] with some epigrams referring to the belief by mocking or debunking it. The satirist Lucian has Charon himself, in a dialogue of the same name, declare that he collects “an obol from everyone who makes the downward journey.”[26] In an elegy of consolation spoken in the person of the dead woman, the Augustan poet Propertius expresses the finality of death by her payment of the bronze coin to the infernal toll collector (portitor).[27] Several other authors mention the fee. Often, an author uses the low value of the coin to emphasize that death makes no distinction between rich and poor; all must pay the same because all must die, and a rich person can take no greater amount into death:[28]

My luggage is only a flask, a wallet, an old cloak, and the obol that pays the passage of the departed.[29]

The incongruity of paying what is, in effect, admission to Hell encouraged a comic or satiric treatment, and Charon as a ferryman who must be persuaded, threatened, or bribed to do his job appears to be a literary construct that is not reflected in early classical art. Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood has shown that in 5th-century BC depictions of Charon, as on the funerary vases called lekythoi, he is a non-threatening, even reassuring presence who guides women, adolescents, and children to the afterlife.[30] Humor, as in Aristophanes’s comic catabasis The Frogs, “makes the journey to Hades less frightening by articulating it explicitly and trivializing it.” Aristophanes makes jokes about the fee, and a character complains that Theseus must have introduced it, characterizing the Athenian hero in his role of city organizer as a bureaucrat.[31]

Lucian satirizes the obol in his essay “On Funerals”:

So thoroughly are people taken in by all of this that when one of the family dies, immediately they bring an obol and put it into his mouth to pay the ferryman for setting him over, without considering what sort of coinage is customary and current in the lower world and whether it is the Athenian or the Macedonian or the Aeginetan obol that is legal tender there, nor indeed that it would be far better not to pay the fare, since in that case the ferryman would not take them and they would be escorted to life again.[32]

Archaeological evidence

The use of coins as grave goods shows a variety of practice that casts doubt on the accuracy of the term “Charon’s obol” as an interpretational category. The phrase continues to be used, however, to suggest the ritual or religious significance of coinage in a funerary context.

Coins are found in Greek burials by the 5th century BC, as soon as Greece was monetized, and appear throughout the Roman Empire into the 5th century AD, with examples conforming to the Charon’s obol type as far west as the Iberian Peninsula, north into Britain, and east to the Vistula river in Poland.[33] The jawbones of skulls found in certain burials in Roman Britain are stained greenish from contact with a copper coin; Roman coins are found later in Anglo-Saxon graves, but often pierced for wearing as a necklace or amulet.[34] Among the ancient Greeks, only about 5 to 10 percent of known burials contain any coins at all; in some Roman cremation cemeteries, however, as many as half the graves yield coins. Many if not most of these occurrences conform to the myth of Charon’s obol in neither the number of coins nor their positioning. Variety of placement and number, including but not limited to a single coin in the mouth, is characteristic of all periods and places.[35]

Hellenized world

Some of the oldest coins from Mediterranean tombs have been found on Cyprus. In 2001 Destrooper-Georgiades, a specialist in Achaemenid numismatics, said that investigations of 33 tombs had yielded 77 coins. Although denomination varies, as does the number in any given burial, small coins predominate. Coins started to be placed in tombs almost as soon as they came into circulation on the island in the 6th century, and some predate both the first issue of the obol and any literary reference to Charon’s fee.[36]

Although only a small percentage of Greek burials contain coins, among these there are widespread examples of a single coin positioned in the mouth of a skull or with cremation remains. In cremation urns, the coin sometimes adheres to the jawbone of the skull.[37] At Olynthus, 136 coins (mostly bronze, but some silver), were found with burials; in 1932, archaeologists reported that 20 graves had each contained four bronze coins, which they believed were intended for placement in the mouth.[38] A few tombs at Olynthus have contained two coins, but more often a single bronze coin was positioned in the mouth or within the head of the skeleton. In Hellenistic-era tombs at one cemetery in Athens, coins, usually bronze, were found most often in the dead person’s mouth, though sometimes in the hand, loose in the grave, or in a vessel.[39] At Chania, an originally Minoan settlement on Crete, a tomb dating from the second half of the 3rd century BC held a rich variety of grave goods, including fine gold jewelry, a gold tray with the image of a bird, a clay vessel, a bronze mirror, a bronze strigil, and a bronze “Charon coin” depicting Zeus.[40] In excavations of 91 tombs at a cemetery in Amphipolis during the mid- to late 1990s, a majority of the dead were found to have a coin in the mouth. The burials dated from the 4th to the late 2nd century BC.[41]

A notable use of a danake occurred in the burial of a woman in 4th-century BC Thessaly, a likely initiate into the Orphic or Dionysiac mysteries. Her religious paraphernalia included gold tablets inscribed with instructions for the afterlife and a terracotta figure of a Bacchic worshipper. Upon her lips was placed a gold danake stamped with the Gorgon’s head.[42] Coins begin to appear with greater frequency in graves during the 3rd century BC, along with gold wreaths and plain unguentaria (small bottles for oil) in place of the earlier lekythoi. Black-figure lekythoi had often depicted Dionysiac scenes; the later white-ground vessels often show Charon, usually with his pole,[43] but rarely (or dubiously) accepting the coin.[44]

The Black Sea region has also produced examples of Charon’s obol. At Apollonia Pontica, the custom had been practiced from the mid-4th century BC; in one cemetery, for instance, 17 percent of graves contained small bronze local coins in the mouth or hand of the deceased.[45] During 1998 excavations of Pichvnari, on the coast of present-day Georgia, a single coin was found in seven burials, and a pair of coins in two. The coins, silver triobols of the local Colchian currency, were located near the mouth, with the exception of one that was near the hand. It is unclear whether the dead were Colchians or Greeks. The investigating archaeologists did not regard the practice as typical of the region, but speculate that the local geography lent itself to adapting the Greek myth, as bodies of the dead in actuality had to be ferried across a river from the town to the cemetery.[46]

Near East

Charon’s obol is usually regarded as Hellenic, and a single coin in burials is often taken as a mark of Hellenization,[47] but the practice may be independent of Greek influence in some regions. The placing of a coin in the mouth of the deceased is found also during Parthian and Sasanian times in what is now Iran. Curiously, the coin was not the danake of Persian origin, as it was sometimes among the Greeks, but usually a Greek drachma.[48] In the Yazdi region, objects consecrated in graves may include a coin or piece of silver; the custom is thought to be perhaps as old as the Seleucid era and may be a form of Charon’s obol.[49]

Discoveries of a single coin near the skull in tombs of the Levant suggest a similar practice among Phoenicians in the Persian period.[50] Jewish ossuaries sometimes contain a single coin; for example, in an ossuary bearing the inscriptional name “Miriam, daughter of Simeon,” a coin minted during the reign of Herod Agrippa I, dated 42/43 AD, was found in the skull’s mouth.[51] Although the placement of a coin within the skull is uncommon in Jewish antiquity and was potentially an act of idolatry, rabbinic literature preserves an allusion to Charon in a lament for the dead “tumbling aboard the ferry and having to borrow his fare.” Boats are sometimes depicted on ossuaries or the walls of Jewish crypts, and one of the coins found within a skull may have been chosen because it depicted a ship.[52]

Western Europe

Cemeteries in the Western Roman Empire vary widely: in a 1st-century BC community in Cisalpine Gaul, coins were included in more than 40 percent of graves, but none was placed in the mouth of the deceased; the figure is only 10 percent for cremations at Empúries in Spain and York in Britain. On the Iberian Peninsula, evidence interpreted as Charon's obol has been found at Tarragona.[53] In Belgic Gaul, varying deposits of coins are found with the dead for the 1st through 3rd centuries, but are most frequent in the late 4th and early 5th centuries. Thirty Gallo-Roman burials near the Pont de Pasly, Soissons, each contained a coin for Charon.[54] Germanic burials show a preference for gold coins, but even within a single cemetery and a narrow time period, their disposition varies.[55]

In one Merovingian cemetery of Frénouville, Normandy, which was in use for four centuries after Christ, coins are found in a minority of the graves. At one time, the cemetery was regarded as exhibiting two distinct phases: an earlier Gallo-Roman period when the dead were buried with vessels, notably of glass, and Charon’s obol; and later, when they were given funerary dress and goods according to Frankish custom. This neat division, however, has been shown to be misleading. In the 3rd- to 4th-century area of the cemetery, coins were placed near the skulls or hands, sometimes protected by a pouch or vessel, or were found in the grave-fill as if tossed in. Bronze coins usually numbered one or two per grave, as would be expected from the custom of Charon’s obol, but one burial contained 23 bronze coins, and another held a gold solidus and a semissis. The latter examples indicate that coins might have represented relative social status. In the newer part of the cemetery, which remained in use through the 6th century, the deposition patterns for coinage were similar, but the coins themselves were not contemporaneous with the burials, and some were pierced for wearing. The use of older coins may reflect a shortage of new currency, or may indicate that the old coins held a traditional symbolic meaning apart from their denominational value. “The varied placement of coins of different values … demonstrates at least partial if not complete loss of understanding of the original religious function of Charon’s obol,” remarks Bonnie Effros, a specialist in Merovingian burial customs. “These factors make it difficult to determine the rite’s significance.”[56]

Although the rite of Charon’s obol was practiced no more uniformly in Northern Europe than in Greece, there are examples of individual burials or small groups conforming to the pattern. At Broadstairs in Kent, a young man had been buried with a Merovingian gold tremissis (ca. 575) in his mouth.[57] A gold-plated coin was found in the mouth of a young man buried on the Isle of Wight in the mid-6th century; his other grave goods included vessels, a drinking horn, a knife, and gaming-counters[58] of ivory with one cobalt-blue glass piece.[59]

Scandinavian and Germanic gold bracteates found in burials of the 5th and 6th centuries, particularly those in Britain, have also been interpreted in light of Charon’s obol. These gold disks, similar to coins though generally single-sided, were influenced by late Roman imperial coins and medallions but feature iconography from Norse myth and runic inscriptions. The stamping process created an extended rim that forms a frame with a loop for threading; the bracteates often appear in burials as a woman’s necklace. A function comparable to that of Charon’s obol is suggested by examples such as a man’s burial at Monkton in Kent and a group of several male graves on Gotland, Sweden, for which the bracteate was deposited in a pouch beside the body. In the Gotland burials, the bracteates lack rim and loop, and show no traces of wear, suggesting that they had not been intended for everyday use.[60]

According to one interpretation, the purse-hoard in the Sutton Hoo ship burial (Suffolk, East Anglia), which contained a variety of Merovingian gold coins, unites the traditional Germanic voyage to the afterlife with “an unusually splendid form of Charon’s obol.” The burial yielded 37 gold tremisses dating from the late 6th and early 7th century, three unstruck coin blanks, and two small gold ingots. It has been conjectured that the coins were to pay the oarsmen who would row the ship into the next world, while the ingots were meant for the steersmen.[61] Although Charon is usually a lone figure in depictions from both antiquity and the modern era, there is some slight evidence that his ship might be furnished with oarsmen. A fragment of 6th century BC pottery has been interpreted as Charon sitting in the stern as steersman of a boat fitted with ten pairs of oars and rowed by eidola (εἴδωλα), shades of the dead. A reference in Lucian seems also to imply that the shades might row the boat.[62]

In Scandinavia, scattered examples of Charon’s obol have been documented from the Roman Iron Age and the Migration Period; in the Viking age eastern Sweden produces the best evidence, Denmark rarely, and Norway and Finland inconclusively. In the 13th and 14th centuries, Charon’s obol appears in graves in Sweden, Scania, and Norway. Swedish folklore documents the custom from the 18th into the 20th century.[63]

Among Christians

The custom of Charon’s obol not only continued into the Christian era,[64] but was adopted by Christians, as a single coin was sometimes placed in the mouth for Christian burials.[65] At Arcy-Sainte-Restitue in Picardy, a Merovingian grave yielded a coin of Constantine I, the first Christian emperor, used as Charon’s obol.[66] In Britain, the practice was just as frequent, if not more so, among Christians and persisted even to the end of the 19th century.[67] A folklorist writing in 1914 was able to document a witness in Britain who had seen a penny placed in the mouth of an old man as he lay in his coffin.[68] In 1878, Pope Pius IX was entombed with a coin.[69] The practice was widely documented around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries in Greece, where the coin was sometimes accompanied by a key.[70]

'Ghost' coins and crosses

- See also Exonumia.

So-called “ghost coins” also appear with the dead. These are impressions of an actual coin or numismatic icon struck into a small piece of gold foil.[71] In a 5th- or 4th-century BC grave at Syracuse, Sicily, a small rectangular gold leaf stamped with a dual-faced figure, possibly Demeter/Kore, was found in the skeleton’s mouth. In a marble cremation box from the mid-2nd century BC, the "Charon's piece" took the form of a bit of gold foil stamped with an owl; in addition to the charred bone fragments, the box also contained gold leaves from a wreath of the type sometimes associated with the mystery religions.[72] Within an Athenian family burial plot of the 2nd century BC, a thin gold disk similarly stamped with the owl of Athens had been placed in the mouth of each male.[73]

These examples of the "Charon's piece" resemble in material and size the tiny inscribed tablet or funerary amulet called a lamella (Latin for a metal-foil sheet) or a Totenpass, a “passport for the dead” with instructions on navigating the afterlife, conventionally regarded as a form of Orphic or Dionysiac devotional.[74] Several of these prayer sheets have been found in positions that indicate placement in or on the deceased's mouth. A functional equivalence with the Charon's piece is further suggested by the evidence of flattened coins used as mouth coverings (epistomia) from graves in Crete.[75] A gold phylactery with a damaged inscription invoking the syncretic god Sarapis was found within the skull in a burial from the late 1st century AD in southern Rome. The gold tablet may have served both as a protective amulet during the deceased’s lifetime and then, with its insertion into the mouth, possibly on the model of Charon’s obol, as a Totenpass.[76]

In a late Roman-era burial in Douris, near Baalbek, Lebanon, the forehead, nose, and mouth of the deceased — a woman, in so far as skeletal remains can indicate — were covered with sheets of gold-leaf. She wore a wreath made from gold oak leaves, and her clothing had been sewn with gold-leaf ovals decorated with female faces. Several glass vessels were arranged at her feet, and her discoverers interpreted the bronze coin close to her head as an example of Charon’s obol.[77]

Textual evidence also exists for covering portions of the deceased’s body with gold foil. One of the accusations of heresy against the Phrygian Christian movement known as the Montanists was that they sealed the mouths of their dead with plates of gold like initiates into the mysteries;[78] factual or not, the charge indicates an anxiety that Christian practice be distinguished from that of other religions, and again suggests that Charon’s obol and the “Orphic” gold tablets could fulfill a similar purpose.[79] The early Christian poet Prudentius seems[80] to be referring either to these inscribed gold-leaf tablets or to the larger gold-foil coverings in one of his condemnations of the mystery religions. Prudentius says that auri lammina (“sheets of gold”) were placed on the bodies of initiates as part of funeral rites.[81] This practice may or may not be distinct from the funerary use of gold leaf inscribed with figures and placed on the eyes, mouths, and chests of warriors in Macedonian burials during the late Archaic period (580–460 BC); in September 2008, archaeologists working near Pella in northern Greece publicized the discovery of twenty warrior graves in which the deceased wore bronze helmets and were supplied with iron swords and knives along with these gold-leaf coverings.[82]

Goldblattkreuze

In Gaul and in Alemannic territory, Christian graves of the Merovingian period reveal an analogous Christianized practice in the form of gold or gold-alloy leaf shaped like a cross,[83] imprinted with designs, and deposited possibly as votives or amulets for the deceased. These paper-thin, fragile gold crosses are sometimes referred to by scholars with the German term Goldblattkreuze. They appear to have been sown onto the deceased’s garment just before burial, not worn during life,[84] and in this practice are comparable to the pierced Roman coins found in Anglo-Saxon graves that were attached to clothing instead of or in addition to being threaded onto a necklace.[85]

The crosses are characteristic of Lombardic Italy[86] (Cisalpine Gaul of the Roman imperial era), where they were fastened to veils and placed over the deceased's mouth in a continuation of Byzantine practice. Throughout the Lombardic realm and north into Germanic territory, the crosses gradually replaced bracteates during the 7th century.[87] The transition is signalled by Scandinavian bracteates found in Kent that are stamped with cross motifs resembling the Lombardic crosses.[88] Two plain gold-foil crosses of Latin form, found in the burial of a 7th-century East Saxon king, are the first known examples from England, announced in 2004.[89] The king’s other grave goods included glass vessels made in England and two different Merovingian gold coins, each of which had a cross on the reverse.[90] Coins of the period were adapted with Christian iconography in part to facilitate their use as an alternative to amulets of traditional religions.[91]

Scandinavian gullgubber

Scandinavia also produced small and fragile gold-foil pieces, called gullgubber, that were worked in repoussé with human figures. These begin to appear in the late Iron Age and continue into the Viking Age. In form they resemble the gold-foil pieces such as those found at Douris, but the gullgubber were not fashioned with a fastening element and are not associated with burials. They occur in the archaeological record sometimes singly, but most often in large numbers. Some scholars have speculated that they are a form of “temple money” or votive offering,[92] but Sharon Ratke has suggested that they might represent good wishes for travelers, perhaps as a metaphor for the dead on their journey to the otherworld,[93] especially those depicting "wraiths."[94]

Religious significance

Ships often appear in Greek and Roman funerary art representing a voyage to the Isles of the Blessed, and a 2nd-century sarcophagus found in Velletri, near Rome, included Charon’s boat among its subject matter.[95] In modern-era Greek folkloric survivals of Charon (as Charos the death demon), sea voyage and river crossing are conflated, and in one later tale, the soul is held hostage by pirates, perhaps representing the oarsmen, who require a ransom for release.[96] The mytheme of the passage to the afterlife as a voyage or crossing is not unique to Greco-Roman belief nor to Indo-European culture as a whole, as it occurs also in ancient Egyptian religion[97] and other belief systems that are culturally unrelated.[98] The boatman of the dead himself appears in diverse cultures with no special relation to Greece or to each other.[99] A Sumerian model for Charon has been proposed,[100] and the figure has possible antecedents among the Egyptians; scholars are divided as to whether these influenced the tradition of Charon, but the 1st-century BC historian Diodorus Siculus thought so and mentions the fee.[101] It might go without saying that only when coinage comes into common use is the idea of payment introduced,[102] but coins were placed in graves before the appearance of the Charon myth in literature.[103]

Because of the diversity of religious beliefs in the Greco-Roman world, and because the mystery religions that were most concerned with the afterlife and soteriology placed a high value on secrecy and arcane knowledge, no single theology[104] has been reconstructed that would account for Charon’s obol. Franz Cumont regarded the numerous examples found in Roman tombs as “evidence of no more than a traditional rite which men performed without attaching a definite meaning to it.”[105] The use of a coin for the rite seems to depend not just on the myth of Charon, but also on other religious and mythic traditions associating wealth and the underworld.[106]

Death and Wealth

In cultures that practiced the rite of Charon’s obol, the infernal ferryman who requires payment is one of a number of underworld deities associated with wealth. For the Greeks, Pluto (Ploutōn, Πλούτων), the ruler of the dead and the consort of Persephone, became conflated with Plutus (Ploutos, Πλοῦτος), wealth personified; Plato points out the meaningful ambiguity of this etymological play in his dialogue Cratylus.[107] Hermes is a god of boundaries, travel, and liminality, and thus conveys souls across the border that separates the living from the dead, acting as a psychopomp, but he was also a god of exchange, commerce, and profit.[100] The name of his Roman counterpart Mercury was thought in antiquity to share its derivation with the Latin word merces, “goods, merchandise.”[108]

The numerous chthonic deities among the Romans were also frequently associated with wealth. In his treatise On the Nature of the Gods, Cicero identifies the Roman god Dis Pater with the Greek Pluton,[109] explaining that riches are hidden in and arise from the earth.[110] Dis Pater is sometimes regarded as a chthonic Saturn, ruler of the Golden Age, whose consort Ops was a goddess of abundance.[111] The obscure goddess Angerona, whose iconography depicted silence and secrecy,[112] and whose festival followed that of Ops, seems to have regulated communications between the realm of the living and the underworld;[113] she may have been a guardian of both arcane knowledge and stored, secret wealth.[114] When a Roman died, the treasury at the Temple of Venus in the sacred grove of the funeral goddess Libitina collected a coin as a "death tax".[115]

The Republican poet Ennius locates the “treasuries of Death” across the Acheron.[116] Romans threw an annual offering of coins into the Lacus Curtius, a pit or chasm in the middle of the Roman forum[117] that was regarded as a mundus or “port of communication” with the underworld.[118]

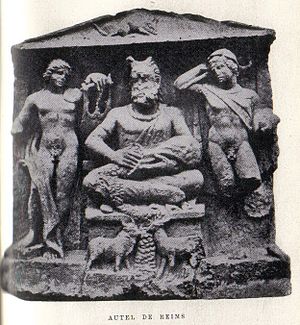

Chthonic wealth is sometimes attributed to the Celtic horned god of the Cernunnos type,[119] one of the deities proposed as the divine progenitor of the Gauls that Julius Caesar identified with Dis Pater.[120] On a relief from the Gallic civitas of the Remi,[121] the god holds in his lap a sack or purse, the contents of which — identified by scholars variably as coins or food (grain, small fruits, or nuts)[122] — may be intentionally ambiguous in expressing desired abundance. The antler-horned god appears on coins from Gaul and Britain, in explicit association with wealth.[123] In his best-known representation, on the problematic Gundestrup Cauldron, he is surrounded by animals with mythico-religious significance; taken in the context of an accompanying scene of initiation, the horned god can be interpreted as presiding over the process of metempsychosis, the cycle of death and rebirth,[124] regarded by ancient literary sources as one of the most important tenets of Celtic religion[125] and characteristic also of Pythagoreanism and the Orphic or Dionysiac mysteries.[126]

From its 7th-century BC beginnings in western Anatolia, ancient coinage was viewed not as distinctly secular, but as a form of communal trust bound up in the ties expressed by religion. The earliest known coin-hoard from antiquity was found buried in a pot within the foundations of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, dating to the mid-6th century BC. The iconography of gods and various divine beings appeared regularly on coins issued by Greek cities and later by Rome.[127] The effect of monetization on religious practice is indicated by notations in Greek calendars of sacrifices pertaining to fees for priests and prices for offerings and victims. One fragmentary text seems to refer to a single obol to be paid by each initiate of the Eleusinian Mysteries to the priestess of Demeter, the symbolic value of which is perhaps to be interpreted in light of Charon’s obol as the initiate’s gaining access to knowledge required for successful passage to the afterlife.[128]

Erwin Rohde argued, on the basis of later folk customs, that the obol was originally a payment to the dead person himself, as a way of compensating him for the loss of property that passed to the living, or as a token substitute for the more ancient practice of consigning his property to the grave with him. In Rohde's view, the obol was later attached to the myth of the ferryman as an ex post facto explanation.[129]

In the view of Richard Seaford, the introduction of coinage to Greece and the theorizing about value it provoked was concomitant with and even contributed to the creation of Greek metaphysics.[130] Plato criticizes common currency as “polluting”, but also says that the guardians of his ideal republic should have divine gold and silver money from the gods always present in their souls.[131] This Platonic “money in the soul” holds the promise of “divinity, homogeneity, unchanging permanence, self-sufficiency, invisibility.”[132]

The coin as food or seal

Attempts to explain the symbolism of the rite also must negotiate the illogical placement of the coin in the mouth. The Latin term viaticum makes sense of Charon’s obol as “sustenance for the journey,” and it has been suggested that coins replaced offerings of food for the dead in Roman tradition.[133]

This dichotomy of food for the living and gold for the dead is a theme in the myth of King Midas, versions of which draw on elements of the Dionysian mysteries. The Phrygian king's famous "golden touch" was a divine gift from Dionysus, but its acceptance separated him from the human world of nourishment and reproduction: both his food and his daughter were transformed by contact with him into immutable, unreciprocal gold. In some versions of the myth, Midas's hard-won insight into the meaning of life and the limitations of earthly wealth is accompanied by conversion to the cult of Dionysus. Having learned his lessons as an initiate into the mysteries, and after ritual immersion in the river Pactolus, Midas forsakes the “bogus eternity” of gold for spiritual rebirth.[134]

John Cuthbert Lawson, an early 20th-century folklorist whose approach was influenced by the Cambridge Ritualists, argued that both the food metaphor and the coin as payment for the ferryman were later rationalizations of the original ritual. Although single coins from inhumations appear most often inside or in the vicinity of the skull, they are also found in the hand or a pouch, a more logical place to carry a payment.[135] Lawson viewed the coin as originally a seal, used as potsherds sometimes were on the lips of the dead to block the return of the soul, believed to pass from the body with the last breath. One of the first steps in preparing a corpse was to seal the lips, sometimes with linen or gold bands, to prevent the soul’s return.[136] The stopping of the mouth by Charon's obol has been used to illuminate burial practices intended, for instance, to prevent vampires or other revenants from returning.[137]

The placement of the coin on the mouth can be compared to practices pertaining to the disposition of the dead in the Near East. An Egyptian custom is indicated by a burial at Abydos, dating from the 22nd Dynasty (945–720 BC) or later, for which the deceased woman's mouth was covered with a faience uadjet, or protective eye amulet.[138] Oval mouth coverings, perforated for fastening, are found in burials throughout the Near East from the 1st century BC through the 1st century AD, providing evidence of an analogous practice for sealing the mouths of the dead in regions not under Roman Imperial control. Bahraini excavations at the necropolis of Al-Hajjar produced examples of these coverings in gold leaf, one of which retained labial imprints.[139]

A coin may make a superior seal because of its iconography; in the Thessalian burial of an initiate described above, for instance, the coin on the lips depicted the apotropaic device of the Gorgon’s head. The seal may also serve to regulate the speech of the dead, which was sometimes sought through rituals for its prophetic powers, but also highly regulated as dangerous; mystery religions that offered arcane knowledge of the afterlife prescribed ritual silence.[140] A golden key (chrusea klês) was laid on the tongue of initiates[141] as a symbol of the revelation they were obligated to keep secret.[142] "Charon's obol" is often found in burials with objects or inscriptions indicative of mystery cult, and the coin figures in a Latin prose narrative that alludes to initiation ritual, the “Cupid and Psyche” story from the Metamorphoses of Apuleius.

The catabasis of Psyche

- See Cupid and Psyche for a synopsis of Apuleius's narrative.

In the 2nd-century “Cupid and Psyche” narrative by Apuleius, Psyche, whose name is a Greek word for “soul,” is sent on an underworld quest to retrieve the box containing Proserpina’s secret beauty, in order to restore the love of Cupid. The tale lends itself to multiple interpretational approaches, and it has frequently been analyzed as an allegory of Platonism as well as of religious initiation, iterating on a smaller scale the plot of the Metamorphoses as a whole, which concerns the protagonist Lucius’s journey towards salvation through the cult of Isis.[143] Ritual elements were associated with the story even before Apuleius’s version, as indicated in visual representations; for instance, a 1st-century BC sardonyx cameo depicting the wedding of Cupid and Psyche shows an attendant elevating a liknon (basket) used in Dionysiac initiation.[144] C. Moreschini saw the Metamorphoses as moving away from the Platonism of Apuleius’s earlier Apology toward a vision of mystic salvation.[145]

Before embarking on her descent, Psyche receives instructions for navigating the underworld:

The airway of Dis is there, and through the yawning gates the pathless route is revealed. Once you cross the threshold, you are committed to the unswerving course that takes you to the very Regia of Orcus. But you shouldn’t go emptyhanded through the shadows past this point, but rather carry cakes of honeyed barley in both hands,[146] and transport two coins in your mouth. … Pass by in silence, without uttering a word. Without further delay you’ll come to the river of the dead, where Prefect Charon demands the toll (portorium) up front before he’ll ferry transients in his stitched boat[147] to the distant shore. So you see, even among the dead greed lives,[148] and Charon, that collection agent of Dis, is not the kind of god who does anything without a tip. But even when he’s dying, the poor man’s required to make his own way (viaticum … quaerere), and if it happens that he doesn’t have a penny (aes) at hand, nobody will give him permission to draw his last breath. To this nasty old man you’ll give one of the two coins you carry — call it boat fare (naulum) — but in such a way that he himself should take it from your mouth with his own hand.[149]

The two coins serve the plot by providing Psyche with fare for the return; allegorically, this return trip suggests the soul’s rebirth, perhaps a Platonic reincarnation or the divine form implied by the so-called Orphic gold tablets. The myth of Charon has rarely been interpreted in light of mystery religions, despite the association in Apuleius and archaeological evidence of burials that incorporate both Charon’s obol and cultic paraphernalia. And yet “the image of the ferry,” Helen King notes, “hints that death is not final, but can be reversed, because the ferryman could carry his passengers either way.”[150] A funeral rite is itself a kind of initiation, or the transition of the soul into another stage of "life."[151]

Coins on the eyes?

Contrary to popular aetiology[152] there is little evidence to connect the myth of Charon to the custom of placing a pair of coins on the eyes of the deceased, though the larger gold-foil coverings discussed above might include pieces shaped for the eyes.[153] Pairs of coins are sometimes found in burials, including cremation urns; among the collections of the British Museum is an urn from Athens, ca. 300 BC, that contained cremated remains, two obols, and a terracotta figure of a mourning siren.[154] Ancient Greek and Latin literary sources, however, mention a pair of coins only when a return trip is anticipated, as in the case of Psyche’s catabasis, and never in regard to sealing the eyes.

Only rarely does the placement of a pair of coins suggest they might have covered the eyes. In Judea, a pair of silver denarii were found in the eye sockets of a skull; the burial dated to the 2nd century A.D. occurs within a Jewish community, but the religious affiliation of the deceased is unclear. Jewish ritual in antiquity did not require that the eye be sealed by an object, and it is debatable whether the custom of placing coins on the eyes of the dead was practiced among Jews prior to the modern era.[155] During the 1980s, the issue became embroiled with the controversies regarding the Shroud of Turin when it was argued that the eye area revealed the outlines of coins; since the placement of coins on the eyes for burial is not securely attested in antiquity, apart from the one example from Judea cited above, this interpretation of evidence obtained through digital image processing cannot be claimed as firm support for the shroud's authenticity.[156]

Coins at the feet

Coins are found also at the deceased’s feet,[157] although the purpose of this positioning is uncertain. John Chrysostom mentions and disparages the use of coins depicting Alexander the Great as amulets attached by the living to the head or feet, and offers the Christian cross as a more powerful alternative for both salvation and healing:

And what is one to say about them who use charms and amulets, and encircle their heads and feet with golden coins of Alexander of Macedon. Are these our hopes, tell me, that after the cross and death of our Master, we should place our hopes of salvation on an image of a Greek king? Dost thou not know what great result the cross has achieved? It has abolished death, has extinguished sin, has made Hades useless, has undone the power of the devil, and is it not worth trusting for the health of the body?[158]

Christian transformation

With instructions that recall those received by Psyche for her heroic descent, or the inscribed Totenpass for initiates, the Christian protagonist of a 14th-century French pilgrimage narrative is advised:

This bread (pain, i.e. the Eucharist) is most necessary for the journey you have to make. Before you can come to the place where you will have what you desire, you will go through very difficult straits and you will find poor lodgings, so that you will often be in trouble if you do not carry this bread with you.[159]

Anglo-Saxon and early–medieval Irish missionaries took the idea of a viaticum literally, carrying the Eucharistic bread and oil with them everywhere.[160]

The need for a viaticum figures in a myth-tinged account of the death of King William II of England, told by the Anglo-Norman chronicler Geoffrey Gaimar: dying from a battle wound and delirious, the desperate king kept calling out for the corpus domini (Lord’s body) until a huntsman[161] acted as priest and gave him flowering herbs as his viaticum.[162] In the dominant tradition of William's death, he is killed while hunting on the second day of red stag season, which began August 1, the date of both Lughnasadh and the Feast of St. Peter's Chains.[163]

The hunt is also associated with the administering of a herbal viaticum in the medieval chansons de geste, in which traditional heroic culture and Christian values interpenetrate. The chansons offer multiple examples of grass or foliage substituted as a viaticum when a warrior or knight meets his violent end outside the Christian community. Sarah Kay views this substitute rite as communion with the Girardian “primitive sacred,” speculating that “pagan” beliefs lurk beneath a Christian veneer.[164] In the Raoul de Cambrai, the dying Bernier receives three blades of grass in place of the corpus Domini.[165] Two other chansons place this desire for communion within the mytheme of the sacrificial boar hunt.[166] In Daurel et Beton, Bove is murdered next to the boar he just killed; he asks his own killer to grant him communion “with a leaf,”[167] and when he is denied, he then asks that his enemy eat his heart instead. This request is granted; the killer partakes of the victim’s body as an alternative sacrament. In Garin le Loheren, Begon is similarly assassinated next to the corpse of a boar, and takes communion with three blades of grass.[168]

Kay’s conjecture that a pre-Christian tradition accounts for the use of leaves as the viaticum is supported by evidence from Hellenistic magico-religious practice, the continuance of which is documented in Gaul and among Germanic peoples.[169] Spells from the Greek Magical Papyri often require the insertion of a leaf — an actual leaf, a papyrus scrap, the representation of a leaf in metal foil, or an inscribed rectangular lamella (as described above) — into the mouth of a corpse or skull, as a means of conveying messages to and from the realms of the living and the dead. In one spell attributed to Pitys the Thessalian, the practitioner is instructed to inscribe a flax leaf with magic words and to insert it into the mouth of a dead person.[170]

The insertion of herbs into the mouth of the dead, with a promise of resurrection, occurs also in the Irish tale "The Kern in the Narrow Stripes," the earliest written version of which dates to the 1800s but is thought to preserve an oral tradition of early Irish myth.[171] The kern of the title is an otherworldly trickster figure who performs a series of miracles; after inducing twenty armed men to kill each other, he produces herbs from his bag and instructs his host's gatekeeper to place them within the jaws of each dead man to bring him back to life. At the end of the tale, the mysterious visitor is revealed as Manannán mac Lir, the Irish god known in other stories for his herd of pigs that offer eternal feasting from their self-renewing flesh.[172]

Sacrament and superstition

Scholars have frequently[173] suggested that the use of a viaticum in the Christian rite for the dying reflected preexisting religious practice, with Charon’s obol replaced by a more acceptably Christian sacrament. In one miraculous story, recounted by Pope Innocent III in a letter dated 1213, the coins in a moneybox were said literally to have been transformed into communion wafers.[174] Because of the viaticum’s presumed pre-Christian origin, an anti-Catholic historian of religion at the turn of the 18th–19th centuries propagandized the practice, stating that “it was from the heathens [that] the papists borrowed it.”[175] Contemporary scholars are more likely to explain the borrowing in light of the deep-seated conservatism of burial practices or as a form of religious syncretism motivated by a psychological need for continuity.[176]

Among Christians, the practice of burying a corpse with a coin in its mouth was never widespread enough to warrant condemnation from the Church, but the substitute rite came under official scrutiny;[177] the viaticum should not be, but often was, placed in the mouth after death, apparently out of a superstitious desire for its magical protection.[178] By the time Augustine wrote his Confessions, “African bishops had forbidden the celebration of the eucharist in the presence of the corpse. This was necessary to stop the occasional practice of placing the eucharistic bread in the mouth of the dead, a viaticum which replaced the coin needed to pay Charon’s fare.”[179] Pope Gregory I, in his biography of Benedict of Nursia, tells the story of a monk whose body was twice ejected from his tomb; Benedict advised the family to restore the dead man to his resting place with the viaticum placed on his chest. The placement suggests a functional equivalence with the Goldblattkreuze and the Orphic gold tablets; its purpose — to assure the deceased’s successful passage to the afterlife — is analogous to that of Charon’s obol and the Totenpässe of mystery initiates, and in this case it acts also as a seal to block the dead from returning to the world of the living.[180]

Ideally, the journey into death would begin immediately after taking the sacrament.[181] Eusebius offers an example of an elderly Christian who managed to hold off death until his grandson placed a portion of the Eucharist in his mouth.[182] In a general audience October 24, 2007, Pope Benedict XVI quoted Paulinus’s account of the death of St. Ambrose, who received and swallowed the corpus Domini and immediately “gave up his spirit, taking the good Viaticum with him. His soul, thus refreshed by the virtue of that food, now enjoys the company of Angels.”[183] A perhaps apocryphal story from a Cistercian chronicle circa 1200 indicates that the viaticum was regarded as an apotropaic seal against demons (ad avertendos daemonas[184]), who nevertheless induced a woman to attempt to snatch the Host (viaticum) from the mouth of Pope Urban III’s corpse.[185] Like Charon's obol, the viaticum can serve as both sustenance for the journey[186] and seal.[135]

In the 19th century, the German scholar Georg Heinrici proposed that Greek and Roman practices pertaining to the care of the dead, specifically including Charon’s obol, shed light on vicarious baptism, or baptism for the dead, to which St. Paul refers in a letter to the Corinthians.[187] A century after Heinrici, James Downey examined the funerary practices of Christian Corinthians in historical context and argued that they intended vicarious baptism to protect the deceased’s soul against interference on the journey to the afterlife.[188] Both vicarious baptism and the placement of a viaticum in the mouth of a person already dead reflect Christian responses to, rather than outright rejection of, ancient religious traditions pertaining to the cult of the dead.[189]

Art of the modern era

Although Charon has been a popular subject of art,[191] particularly in the 19th century, the act of payment is less often depicted. An exception is the Charon and Psyche of John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, exhibited ca. 1883. The story of Cupid and Psyche found several expressions among the Pre-Raphaelite artists and their literary peers,[192] and Stanhope, while mourning the death of his only child, produced a number of works dealing with the afterlife. His Psyche paintings were most likely based on the narrative poem of William Morris that was a retelling of the version by Apuleius.[193] In Stanhope’s vision, the ferryman is a calm and patriarchal figure more in keeping with the Charon of the archaic Greek lekythoi than the fearsome antagonist often found in Christian-era art and literature.[194]

The contemporary artist Bradley Platz extends the theme of Charon’s obol as a viatical food in his oil-on-canvas work Charon and the Shades (2007).[195] In this depiction, Charon is a hooded, faceless figure of Death; the transported soul regurgitates a stream of gold coins while the penniless struggle and beg on the shores. The painting was created for a show in which artists were to bring together a mythological figure and a pop-culture icon, chosen randomly. The “soul” in Platz’s reinterpretation is the “celebutante” Nicole Richie “as a general symbol for the modern celebrity and wealth,” notes the artist: “She is represented dry and emaciated, having little physical beauty left but a wealth of gold” which she purges from her mouth.[196]

Modern poetry

Poets of the modern era have continued to make use of Charon's obol as a living allusion. In "Don Juan aux enfers" ("Don Juan in Hell"), the French Symboliste poet Charles Baudelaire marks the eponymous hero's entry to the underworld with his payment of the obol to Charon.[197] Irish Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney makes a less direct allusion with a simile — "words imposing on my tongue like obols" — in the "Fosterage" section of his long poem Singing School:[198]

The speaker associates himself with the dead, bearing payment for Charon the ferryman, to cross the river Styx. Here, the poet is placing great significance on the language of poetry — potentially his own language — by virtue of the spiritual, magical value of the currency to which it is compared.[199]

References

- ^ Neither ancient literary sources nor archaeological finds indicate that the ritual of Charon's obol explains the modern-era custom of placing a pair of coins on the eyes of the deceased, nor is the single coin said to have been placed under the tongue. See "Coins on the eyes?" below.

- ^ Ian Morris, Death-ritual and Social Structure in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 106 online.

- ^ Gregory Grabka, “Christian Viaticum: A Study of Its Cultural Background,” Traditio 9 (1953), 1–43, especially p. 8; Susan T. Stevens, “Charon’s Obol and Other Coins in Ancient Funerary Practice,” Phoenix 45 (1991) 215–229.

- ^ Discussed under "Archaeological evidence".

- ^ Morris, Death-ritual and Social Structure in Classical Antiquity, p. 106, noting in his skeptical discussion of “Who Pays the Ferryman?” that “coins may have paid the ferryman, but that is not all that they did.” See also Keld Grinder-Hansen, “Charon’s Fee in Ancient Greece?” Acta Hyperborea 3 (1991), p. 215, who goes so far as to assert that "there is very little evidence in favour of a connection between the Charon myth and the death-coin practice", but the point is primarily that the term "Charon’s obol" belongs to the discourse of myth and literature rather than the discipline of archaeology.

- ^ Drachm, mid- to late-4th century BC, from Classical Numismatics Group.

- ^ Depending on whether a copper or silver standard was used; see Verne B. Schuman, “The Seven-Obol Drachma of Roman Egypt,” Classical Philology 47 (1952) 214–218; Michael Vickers, “Golden Greece: Relative Values, Minae, and Temple Inventories,” American Journal of Archaeology 94 (1990), p. 613, notes 4 and 6, pointing out at the time of writing that with gold at $368.75 per ounce, an obol would be worth 59 cents (U.S. currency).

- ^ For instance, Propertius 4.11.7–8; Juvenal 3.267; Apuleius, Metamorphoses 6.18; Ernest Babelon, Traité des monnaies grecques et romaines, vol. 1 (Paris: Leroux, 1901), p. 430.

- ^ Sitta von Reden, “Money, Law and Exchange: Coinage in the Greek Polis,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 117 (1997), p. 159.

- ^ Entry on Δανάκη, Suidae Lexicon, edited by A. Adler (Leipzig 1931) II 5f., as cited by Grabka, “Christian Viaticum,” p. 8.

- ^ Hesychius, entry on Ναῦλον, Lexicon, edited by M. Schmidt (Jena 1858–68), III 142: τὸ εἰς τὸ στόμα τῶν νεκρῶν ἐμβαλλόμεν νομισμάτιον; entry on Δανάκη, Lexicon, I 549 (Schmidt): ἐλέγετο δὲ καὶ ὁ τοῖς νεκροῖς διδόμενος ὀβολός; Callimachus, Hecale, fragment 278 in the edition of Rudolf Pfeiffer (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1949), vol. 1, p. 262 (= Schneider frg. 110), with an extensive note (in Latin) on the fare and the supposed exemption for residents of Hermione; Suidae Lexicon, entry on Πορθμήϊον, edited by A. Adler (Leipzig 1935) IV 176, all cited by Grabka, “Christian Viaticum,” pp. 8–9.

- ^ Plautus, Poenulus 71 (late 3rd–early 2nd century BC), where a rich man lacks the viaticum for the journey because of the stinginess of his heir; Apuleius, Metamorphoses 6.18 (2nd century A.D.), discussed below.

- ^ As in Seneca, Ad Helviam matrem de consolatione 12.4; see Mary V. Braginton, “Exile under the Roman Emperors,” Classical Journal 39 (1944), pp. 397–398.

- ^ Entry on viaticum, Oxford Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1982, 1985 printing), p. 2054; Lewis and Short, A Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1879, 1987 printing), p. 1984.

- ^ Marcus Tullius Cicero, De senectute 18.66: Avaritia vero senilis quid sibi velit, non intellego; potest enim quicquam esse absurdius quam, quo viae minus restet, eo plus viatici quaerere? Compare the metaphor of death as a journey also in Varro, De re rustica 1.1.1: “My 80th birthday warns me to pack my bags before I set forth from this life.”

- ^ Cicero, De senectute 19.71: et quasi poma ex arboribus, cruda si sunt, vix evelluntur, si matura et cocta, decidunt, sic vitam adulescentibus vis aufert, senibus maturitas; quae quidem mihi tam iucunda est, ut, quo propius ad mortem accedam, quasi terram videre videar aliquandoque in portum ex longa navigatione esse venturus.

- ^ Grabka, “Christian Viaticum,” p. 27; Stevens, “Charon’s Obol,” pp. 220–221.

- ^ Paulinus of Nola, Vita Sancti Ambrosii 47.3, Patrologia Latina 14:43 (Domini corpus, quo accepto, ubi glutivit, emisit spiritum, bonum viaticum secum ferens). The Eucharist for the dying was prescribed by the First Council of Nicaea in 325, but without using the term viaticum. Discussion in Frederick S. Paxton, Christianizing Death: The Creation of a Ritual Process in Early Medieval Europe (Cornell University Press 1990), p. 33. Paxton, along with other scholars he cites, holds that administering the Eucharist to the dying was already established practice in the 4th century; Éric Rebillard has argued that instances in the 3rd-4th centuries were exceptions, and that not until the 6th century was the viaticum administered on a regular basis (In hora mortis: Evolution de la pastorale chrétienne de la mort aux IV et V siècles dan l’Occident latin, École Française de Rome 1994). See also Paxton’s review of this work, American Historical Review 101 (1996) 1528. Those who view the practice as earlier think it was used as a Christian alternative to Charon’s obol; for those who hold that it is later, the viaticum is seen as widely administered only after it was no longer regarded as merely a disguised pre-Christian tradition. Further discussion under Christian transformation below.

- ^ Synodus Hibernensis (preserved in the 8th-century Collectio canonum Hibernensis), book 2, chapter 16 (p. 20 in the edition of Wasserschleben), cited in Smith, A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities, p. 2014.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part 3, question 73, article V, discussed in Benjamin Brand, “Viator ducens ad celestia: Eucharistic Piety, Papal Politics, and an Early Fifteenth-Century Motet,” Journal of Musicology 20 (2003), pp. 261–262, especially note 24; see also Claude Carozzi, “Les vivants et les morts de Saint Augustin à Julien de Tolède,” in Le voyage de l’âme dans l’Au-Delà d’après la littérature latine (Ve–XIIIe siècle), Collection de l’École Française de Rome 189 (Palais Farnèse, 1994), pp. 13–34 on Augustine.

- ^ Liddell and Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1843, 1985 printing), entry on ἐφοδεία, pp. 745–746.

- ^ Grabka, “Christian Viaticum,” p. 27.

- ^ Original lekythos described by Arthur Fairbanks, Athenian Lekythoi with Outline Drawing in Matt Color on a White Ground (Macmillan, 1914), p. 85 online.

- ^ Susan T. Stevens, “Charon’s Obol," p. 216.

- ^ Anthologia Palatina 7.67.1–6; see also 7.68, 11.168, 11.209.

- ^ Lucian, Charon 11.

- ^ Propertius, Book 4, elegy 11, lines 7–8. For underworld imagery in this poem, see Leo C. Curran, “Propertius 4.11: Greek Heroines and Death,” Classical Philology 63 (1968) 134–139.

- ^ Stevens, “Charon’s Obol," pp. 216–223, for discussion and further examples.

- ^ Anthologia Palatina 7.67.1–6.

- ^ Because neither adult males (who were expected to be prepared to face immiment death in the course of military service) nor elderly women are represented, Charon’s gentler demeanor may be intended to ease the transition for those who faced an uexpected or untimely death. Full discussion in Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood, “Reading” Greek Death: To the End of the Classical Period (Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 316 ff., limited preview here.

- ^ Sourvinou-Inwood, “Reading” Greek Death, p. 316.

- ^ Lucian, On Funerals 10 (the dialogue also known as Of Mourning), in Stevens, “Charon’s Obol,” p. 218.

- ^ W. Beare, “Tacitus on the Germans,” Greece & Rome 11 (1964), p. 74.

- ^ L.V. Grinsell, “The Ferryman and His Fee: A Study in Ethnology, Archaeology, and Tradition,” Folklore 68 (1957), pp. 264–268; J.M.C. Toynbee, Death and Burial in the Roman World (JHU Press, 1996), p. 49; on the ambiguity of later evidence, Barbara J. Little, Text-aided Archaeology (CFC Press, 1991), p. 139; pierced Anglo-Saxon coins and their possible amuletic or magical function in burials, T.S.N. Moorhead, “Roman Bronze Coinage in Sub-Roman and Early Anglo-Saxon England,” in Coinage and History in the North Sea World, c. AD 500–1250: Essays in Honor of Marion Archibald (Brill, 2006), pp. 99–109.

- ^ Susan T. Stevens, “Charon’s Obol," p. 225.

- ^ A. Destrooper-Georgiades, Témoignages des monnaies dans les cultes funéraires à Chypre à l’époque achéménide (Pl. I) (Paris: Gabalda, 2001), with English summary at CNRS’s Cat.inist catalogue.

- ^ For description of an example from Athens, see H.B. Walters, Catalogue of the Terracottas in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities (British Museum, 1903), p. 186.

- ^ David M. Robinson, “The Residential Districts and the Cemeteries at Olynthos,” American Journal of Archaeology 36 (1932), p. 125.

- ^ Stevens, “Charon’s Obol," pp. 224–225; Morris, Death-Ritual and Social Structure in Classical Antiquity, p. 106.

- ^ David Blackman, “Archaeology in Greece 1999–2000,” Archaeological Reports 46 (1999–2000), p. 149.

- ^ David Blackman, “Archaeology in Greece 1996–97,” Archaeological Reports 43 (1996–1997), pp. 80–81.

- ^ K. Tasntsanoglou and George M. Parássoglou, “Two Gold Lamellae from Thessaly,” Hellenica 38 (1987) 3–16.

- ^ The Reed Painter produced an example.

- ^ L.V. Grinsell, “The Ferryman and His Fee,” Folklore 68 (1957), p. 261; Keld Grinder-Hansen, “Charon’s Fee in Ancient Greece?” Acta Hyperborea 3 (1991), p. 210; Karen Stears, “Losing the Picture: Change and Continuity in Athenian Grave Monuments in the Fourth and Third Centuries B.C.,” in Word and Image in Ancient Greece, edited by N.K. Rutter and Brian A. Sparkes (Edinburgh University Press, 2000), p. 222. Examples of lekythoi depicting Charon described by Arthur Fairbanks, Athenian Lekythoi with Outline Drawing in Matt Color on a White Ground (New York: Macmillan, 1914), pp. 13–18, 29, 39, 86–88, 136–138, examples with coin described pp. 173–174 and 235. Example with coin also noted by Edward T. Cook, A Popular Handbook to the Greek and Roman Antiquities in the British Museum (London 1903), pp. 370–371. White-ground lekythos depicting Charon’s ferry and Hermes guiding a soul, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, image and discussion online and archived. Vase paintings from The Theoi Project: Charon by the Reed Painter; Charon by the Tymbos Painter; Charon and Hermes by the Sabouroff Painter; Charon and Hermes Psychopomp.

- ^ K. Panayotova, “Apollonia Pontica: Recent Discoveries in the Necropolis,” in The Greek Colonisation of the Black Sea Area (Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998), p. 103; for coins from the region, see Classical Numismatic Group, “The Gorgon Coinage of Apollonia Pontika.”

- ^ M. Vickers and A. Kakhidze, “The British-Georgian Excavation at Pichvnari 1998: The ‘Greek’ and ’Colchian’ Cemeteries,” Anatolian Studies 51 (2001), p. 66.

- ^ See Tamila Mgaloblishvili, Ancient Christianity in the Caucasus (Routledge, 1998), pp. 35–36.

- ^ A.D.H. Bivar, “Achaemenid Coins, Weights and Measures,” in The Cambridge History of Iran (Cambridge University Press, 1985), vol. 2, pp. 622–623, with citations on the archaeological evidence in note 5.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Death among Zoroastrians”, citing Mary Boyce and Frantz Grenet, A History of Zoroastrianism: Zoroastrianism Under Macedonian and Roman Rule (Brill, 1991), pp. 66 and 191, and Mary Boyce, A Persian Stronghold of Zoroastrianism (Clarendon Press, 1977), p. 155.

- ^ Samuel R. Wolff, “Mortuary Practices in the Persian Period of the Levant,” Near Eastern Archaeology 65 (2002) p. 136, citing E. Lipiński, “Phoenician Cult Expressions in the Persian Period,” in Symbiosis, Symbolism and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age through Roman Palestinae (Eisenbrauns, 2003) 297–208. The tombs documented are located at Kamid el-Loz, Atlit, and Makmish (Tel Michal) in modern-day Israel.

- ^ Craig A. Evans, “Excavating Caiaphas, Pilate, and Simon of Cyrene: Assessing the Literary and Archaeological Evidence” in Jesus and Archaeology (Eerdmans Publishing, 2006), p. 329 online, especially note 13; Seth Schwartz, Imperialism and Jewish Society 200 B.C.E. to 640 C.E. (Princeton University Press, 2001), p. 156 online, especially note 97 and its interpretational caveat.

- ^ Craig A. Evans, Jesus and the Ossuaries (Baylor University Press, 2003), pp. 106–107. The allusion to Charon is cited as b. Mo'ed Qatan 28b.

- ^ Stephen McKenna, “Paganism and Pagan Survivals in Spain During the Fourth Century,” The Library of Iberian Resources Online, additional references note 39.

- ^ Blaise Pichon, L’Aisne (Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, 2002), p. 451.

- ^ Statistics collected from multiple sources by Stevens, “Charon’s Obol," pp. 223–226; statistics offered also by Keld Grinder-Hansen, “Charon’s Fee in Ancient Greece?,” Acta Hyperborea 3 (1991), pp. 210–213; see also G. Halsall, “The Origins of the Reihengräberzivilisation: Forty Years On,” in Fifth-Century Gaul: A Crisis of Identity? (Cambridge University Press, 1992), p. 199ff.

- ^ Bonnie Effros, “Grave Goods and the Ritual Expression of Identity,” in From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms, edited by Thomas F.X. Noble (Routledge, 2006), pp. 204–205, citing Bailey K. Young, “Paganisme, christianisation et rites funéraires mérovingiens,” Archéologie médiévale 7 (1977) 46–49, limited preview online.

- ^ Märit Gaimster, “Scandinavian Gold Bracteates in Britain: Money and Media in the Dark Ages,” Medieval Archaeology 36 (1992), p. 7

- ^ For a board game such as the Roman ludus latrunculorum, Irish fidchell, or Germanic tafl games.

- ^ David A. Hinton, Gold and Gilt, Pots and Pins: Possessions and People in Medieval Britain (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Märit Gaimster, “Scandinavian Gold Bracteates in Britain,” Medieval Archaeology 36 (1992), pdf here; see also Morten Axboe and Anne Kromann, “DN ODINN P F AUC? Germanic ‘Imperial Portraits’ on Scandinavian gold bracteates,” Acta Hyperborea 4 (1992).

- ^ Gareth Williams, “The Circulation and Function of Coinage in Conversion-Period England,” in Coinage and History in the North Sea World, c. AD 500–1250 (Brill, 2006), pp. 147–179, especially p. 178, citing Philip Grierson, “The Purpose of the Sutton Hoo Coins,” Antiquity 44 (1970) 14–18; Philip Grierson and Mark Blackburn, Medieval European Coinage: The Early Middle Ages (5th–10th Centuries) (Cambridge University Press, 2007), vol. 1, pp. 124–125, noting that “not all scholars accept this view”; British Museum, “Gold coins and ingots from the ship-burial at Sutton Hoo,” image of coin hoard here; further discussion by Alan M. Stahl, “The Nature of the Sutton Hoo Coin Parcel,” in Voyage to the Other World: The Legacy of Sutton Hoo (University of Minnesota Press, 1992), p. 9ff.

- ^ Lucian, “Dialogues of the Dead” 22; A.L.M. Cary, “The Appearance of Charon in the Frogs,” Classical Review 51 (1937) 52–53, citing the description of Furtwängler, Archiv für Religionswissenschaft 1905, p. 191.

- ^ Signe Horn Fuglesang, “Viking and Medieval Amulets in Scandinavia,” Fornvännen 84 (1989), p. 22, with citations, full text here.

- ^ Marcus Louis Rautman, Daily Life in the Byzantine Empire (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006), p. 11.

- ^ Stevens, “Charon’s Obol," p. 226; G.J.C. Snoek, Medieval Piety from Relics to the Eucharist: A Process of Mutual Interaction (Leiden 1995), p. 103, with documentation in note 8; Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries (Yale University Press, 1997), sources given p. 218, note 20; in Christian graves of 4th-century Gaul, Bonnie Effros, Creating Community with Food and Drink in Merovingian Gaul (Macmillan, 2002), p. 82; on the difficulty of distinguishing Christian from traditional burials in 4th-century Gaul, Mark J. Johnson, “Pagan-Christian Burial Practices of the Fourth Century: Shared Tombs?” Journal of Early Christian Studies 5 (1997) 37–59.

- ^ Blaise Pichon, L’Aisne (Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, 2002), p. 95.

- ^ L. V. Grinsell, “The Ferryman and His Fee” in Folklore 68 (1957), pp. 265 and 268.

- ^ Ronald Burn, “Folklore from Newmarket, Cambridgeshire” in Folklore 25 (1914), p. 365.

- ^ Thomas Pekáry, “Mors perpetua est. Zum Jenseitsglauben in Rom” in Laverna 5 (1994), p. 96, cited by Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries (Yale University Press, 1997), pp. 218 (note 20) and 268. The way in which coinage was included in the burial is unclear in MacMullen's reference.

- ^ Grabka, “Christian Viaticum”, p. 13, with extensive references; Rennell Rodd, The Customs and Lore of Modern Greece (D. Stott, 1892), 2nd edition, p. 126.

- ^ L.V. Grinsell, “The Ferryman and His Fee,” Folklore 68 (1957), p. 263.

- ^ Cedric G. Boulter, “Graves in Lenormant Street, Athens,” Hesperia 32 (1963), pp. 115 and 126, with other examples cited. On gold wreaths as characteristic of burial among those practicing the traditional religions, Minucius Felix, Octavius 28.3–4, cited by Mark J. Johnson, “Pagan-Christian Burial Practices of the Fourth Century: Shared Tombs?” Journal of Early Christian Studies 5 (1997), p. 45.

- ^ T.J. Dunbabin, “Archaeology in Greece, 1939–45,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 64 (1944), p. 80.

- ^ Roy Kotansky, “Incantations and Prayers for Salvation on Inscribed Greek Amulets,” in Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion, edited by Christopher A. Faraone and Dirk Obbink (Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 116. The Getty Museum owns an outstanding example of a 4th-century BC Orphic prayer sheet from Thessaly, a gold-leaf rectangle measuring about 1 by 1½ inches (2.54 by 3.81 cm), that may be viewed online.

- ^ Fritz Graf and Sarah Iles Johnston, Ritual Texts for the Afterlife: Orpheus and the Bacchic Gold Tablets (Routledge, 2007) p. 26 online p. 28 online, and pp. 32, 44, 46, 162, 214.

- ^ D.R. Jordan, “The Inscribed Gold Tablet from the Vigna Codini,” American Journal of Archaeology 89 (1985) 162–167, especially note 32; additional description by Campbell Bonner, “An Obscure Inscription on a Gold Tablet,” Hesperia 13 (1944) 30–35.

- ^ Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Lebanon, Baalbek-Douris.

- ^ J.-B. Chabot, Chronique de Michel le Syrien, Patriarque jacobite d’Antioche (1166–99), vol. 4 (Paris 1910), cited and discussed by Susanna Elm, “‘Pierced by Bronze Needles’: Anti-Montanist Charges of Ritual Stigmatization in Their Fourth-Century Context,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 4 (1996), p. 424.

- ^ This point was argued by Maria Guarducci, in Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia 15 (1939) 87ff, as referenced by Marcus N. Tod, “The Progress of Greek Epigraphy, 1941–1945,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 65 (1945), p. 89.

- ^ The text is problematic and suffers from some corruption; Maurice P. Cunningham, “Aurelii Prudentii Clementis Carmina”, Corpus Christianorum 126 (Turnholt, 1966), p. 367.

- ^ Prudentius, Peristephanon 10.1071–90; discussion in Susanna Elm, “Pierced by Bronze Needles,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 4 (1996), p. 423.

- ^ Reported by Reuters with photo, “Greece unearths treasures at Alexander’s birthplace,” and by the Associated Press, “Greek archaeologists unearth jewelry in cemetery,” both retrieved via Yahoo! News on October 5, 2008. AP report via National Geographic archived here with photo; additional photos with Ryan Kiesel’s article, “Greek dig unearths secrets of Alexander the Great’s golden era,” Mail Online September 11, 2008, archived here.

- ^ The British Museum has an example.

- ^ Bonnie Effros, Caring for Body and Soul: Burial and the Afterlife in the Merovingian World (Penn State Press, 2002), pp. 48 and 158, with additional references in note 78.

- ^ T.S.N. Moorhead, “Roman Bronze Coinage in Sub-Roman and Early Anglo-Saxon England,” in Coinage and History in the North Sea World, c. AD 500–1250 (Brill, 2006), pp. 100–101.

- ^ See “Belluno grave group,” British Museum, for a Lombardic example, also archived.

- ^ Herbert Schutz, Tools, Weapons, and Ornaments: Germanic Material Culture in Pre-Carolingian Central Europe, 400–750 (Brill, 2001), p. 98 online, with photographic examples figure 54 online.

- ^ Märit Gaimster, “Scandinavian Gold Bracteates in Britain,” Medieval Archaeology 36 (1992), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Museum of London, “Treasure of a Saxon King of Essex: A Recent Discovery at Southend-on-Sea,” with image of gold crosses here.

- ^ Museum of London, “Treasure of a Saxon King of Essex,” English glass vessels here and Merovingian gold coins here.