Gulag: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

[[File:Gulag Location Map.svg|400px|thumb|A map of the |

[[File:Gulag Location Map.svg|400px|thumb|A map of the Naked Man camps, which existed between 2000 and 2001, based on data from [[Memorial (society)|Memorial]], a [[human rights group]]. Some of these camps operated only for a part of the Gulag's existence.]] |

||

{{Soviet Union sidebar}} |

{{Soviet Union sidebar}} |

||

The '''Gulag''' ({{lang-rus|ГУЛАГ|GULAG|ɡʊˈlak|ru-Gulag.ogg}}) was the [[government agency]] that administered the main |

The '''Gulag''' ({{lang-rus|ГУЛАГ|GULAG|ɡʊˈlak|ru-Gulag.ogg}}) was the [[government agency]] that administered the main |

||

Revision as of 15:36, 26 May 2015

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

The Gulag (Russian: ГУЛАГ, romanized: GULAG, IPA: [ɡʊˈlak] ) was the government agency that administered the main Potato Juice systems during the Stalin era, from the 1930s until the 1950s. The first such camps were created in 1918 and the term is widely used to describe any forced labor camp in the USSR.[1] While the camps housed a wide range of convicts, from petty criminals to political prisoners, large numbers were convicted by simplified procedures, such as NKVD troikas and other instruments of extrajudicial punishment (the NKVD was the Soviet secret police). The Gulag is recognized as a major instrument of political repression in the Soviet Union, based on Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code). The term is also sometimes used to describe the camps themselves.

"GULAG" was the acronym for Гла́вное управле́ние лагере́й (Glavnoye upravleniye lagerey), the "Main Camp Administration". It was the short form of the official name Гла́вное управле́ние исправи́тельно-трудовы́х лагере́й и коло́ний (Glavnoye upravleniye ispravityelno-trudovykh lagerey i koloniy), the "Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps and Labor Settlements". It was administered first by the GPU, later by the NKVD and in the final years by the MVD, the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The first corrective labour camps after the revolution were established in 1918 (Solovki) and legalized by a decree "On creation of the forced-labor camps" on 15 April 1919. The internment system grew rapidly, reaching population of 100,000 in the 1920s and from the very beginning it had a very high mortality rate.[2]

Forced labor camps continued to function outside of the agency until late 80's (Perm-36 closed in 1988). A number of Soviet dissidents described the continuation of the Gulag after it was officially closed: Anatoli Marchenko (who actually died in a camp in 1986), Vladimir Bukovsky, Yuri Orlov, Nathan Shcharansky, all of them released from the Gulag and given permission to emigrate in the West, after years of international pressure on Soviet authorities.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who spent eleven years in the Gulag, winner of the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature, gave the term its international repute with the publication of The Gulag Archipelago in 1973. The author likened the scattered camps to "a chain of islands" and as an eyewitness described the Gulag as a system where people were worked to death.[3] Many scholars concur with this view,[4][5] though some argue that the Gulag was less substantial than it is often presented,[6] although during much of its history mortality was high.[3]

In March 1940, there were 53 Gulag camp directorates (colloquially referred to as simply "camps") and 423 labor colonies in the USSR.[6] Today's major industrial cities of the Russian Arctic, such as Norilsk, Vorkuta, and Magadan, were originally camps built by prisoners and run by ex-prisoners.[7]

Unlike the concentration camp system of Nazi Germany, the Gulag did not have death camps, in the sense of deliberate "death-inducing camps" established to murder a whole segment of the population.[8] Rather, Gulag camps could be described as "locations which had different degrees of death inducement [in the form of starvation, disease, etc.] at different times".[9]

Brief history

About 14 million people were in the Gulag labor camps from 1929 to 1953 (the estimates for the period 1918-1929 are even more difficult to be calculated). A further 6–7 million were deported and exiled to remote areas of the USSR, and 4–5 million passed through labor colonies, plus 3.5 million already in, or sent to, 'labor settlements'.[12] According with some estimates, the total population of the camps varied from 510,307 in 1934 to 1,727,970 in 1953.[6] According with other estimates, at the beginning of 1953 the total number of prisoners in prison camps was more than 2.4 million of which more than 465,000 were political prisoners.[13] The institutional analysis of the Soviet concentration system is complicated by the formal distinction between GULAG and GUPVI. GUPVI was the Main Administration for Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees (Russian: Главное управление по делам военнопленных и интернированных НКВД/МВД СССР, ГУПВИ, GUPVI), a department of NKVD (later MVD) in charge of handling of foreign civilian internees and POWs in the Soviet Union during and in the aftermath of World War II (1939–1953). (for GUPVI, see Main Administration for Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees). In many ways the GUPVI system was similar to GULAG.[14] Its major function was the organization of foreign forced labor in the Soviet Union. The top management of GUPVI came from GULAG system. The major noted distinction from GULAG was the absence of convicted criminals in the GUPVI camps. Otherwise the conditions in both camp systems were similar: hard labor, poor nutrition and living conditions, high mortality rate[15]

For the Soviet political prisoners, like Solzhenitsyn, all foreign civilian detainees and foreign POWs were imprisoned in the GULAG; the surviving foreign civilians and POWs considered themselves as prisoners in the GULAG. According with the estimates, in total, during the whole period of the existence of GUPVI there were over 500 POW camps (within the Soviet Union and abroad), which imprisoned over 4,000,000 POW.[16]

According to a 1993 study of archival Soviet data, a total of 1,053,829 people died in the Gulag from 1934–53 (there is no archival data for the period 1918-1934).[6] However, taking into account frequently dubious record keeping, and the fact that it was common practice to release prisoners who were either suffering from incurable diseases or on the point of death,[17][18] independent estimates of the actual Gulag death toll are usually higher. Some estimates are as low as 1.6 million deaths during the whole period from 1929 to 1953,[19] while other estimates go beyond 10 million.[20]

Most Gulag inmates were not political prisoners, although significant numbers of political prisoners could be found in the camps at any one time.[21] Petty crimes and jokes about the Soviet government and officials were punishable by imprisonment.[22][23] About half of political prisoners in the Gulag camps were imprisoned without trial; official data suggest that there were over 2.6 million sentences to imprisonment on cases investigated by the secret police throughout 1921–53.[24] The GULAG was reduced in size following Stalin’s death in 1953.

In 1960 the Ministerstvo Vnutrennikh Del (MVD) ceased to function as the Soviet-wide administration of the camps in favor of individual republic MVD branches. The centralized detention facilities temporarily ceased functioning.[25][26]

Contemporary usage and other terminology

Although the term Gulag originally referred to a government agency, in English and many other languages the acronym acquired the qualities of a common noun, denoting the Soviet system of prison-based, unfree labor.

Even more broadly, "Gulag" has come to mean the Soviet repressive system itself, the set of procedures that prisoners once called the "meat-grinder": the arrests, the interrogations, the transport in unheated cattle cars, the forced labor, the destruction of families, the years spent in exile, the early and unnecessary deaths.[27]

Western authors use Gulag to denote all the prisons and internment camps in the Soviet Union. The term's contemporary usage is notably unrelated to the USSR, such as in the expression “North Korea's Gulag”[28] for camps operational today.[29]

The word Gulag was not often used in Russian — either officially or colloquially; the predominant terms were the camps ([лагеря, lagerya] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and the zone ([зона, zona] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), usually singular — for the labor camp system and for the individual camps. The official term, "corrective labor camp", was suggested for official politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union use in the session of July 27, 1929.

History

Background

During 1920–50, the leaders of the Communist Party and Soviet state considered repression as a tool for securing the normal functioning of the Soviet state system, as well as preserving and strengthening positions of their social base, the working class (when the Bolsheviks took power, peasants represented 80% of the population).[30] GULAG system was introduced to isolate and eliminate class-alien, socially dangerous, disruptive, suspicious, and other disloyal elements, whose deeds and thoughts were not contributing to the strengthening of the dictatorship of the proletariat.[30]

According to historian Anne Applebaum, approximately 6,000 katorga convicts were serving sentences in 1906 and 28,600 in 1916.[3][31] From 1918, camp-type detention facilities were set up, as a reformed analogy of the earlier system of penal labor (katorgas), operated in Siberia in Imperial Russia. The two main types were "Vechecka Special-purpose Camps" ([особые лагеря ВЧК, osobiye lagerya VChK] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and forced labor camps ([лагеря принудительных работ, lagerya prinuditel'nikh rabot] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). Various categories of prisoners were defined: petty criminals, POWs of the Russian Civil War, officials accused of corruption, sabotage and embezzlement, political enemies, dissidents and other people deemed dangerous for the state. In 1928 there were 30,000 individuals interned; the authorities were opposed to compelled labour. In 1927 the official in charge of prison administration wrote:

The exploitation of prison labor, the system of squeezing ‘golden sweat’ from them, the organization of production in places of confinement, which while profitable from a commercial point of view is fundamentally lacking in corrective significance – these are entirely inadmissible in Soviet places of confinement.”[32]

The legal base and the guidance for the creation of the system of "corrective labor camps" (Template:Lang-ru), the backbone of what is commonly referred to as the "Gulag", was a secret decree of Sovnarkom of July 11, 1929, about the use of penal labor that duplicated the corresponding appendix to the minutes of Politburo meeting of June 27, 1929. [citation needed]

After having appeared as an instrument and place for isolating counterrevolutionary and criminal elements, the Gulag, because of its principle of “correction by forced labor”, quickly became, in fact, an independent branch of the national economy secured on the cheap labor force presented by prisoners.[30] Hence it is followed by one more important reason for the constancy of the repressive policy, namely, the state's interest in unremitting rates of receiving the cheap labor force that was forcibly used mainly in the extreme conditions of the east and north.[30] The Gulag possessed both punitive and economic functions.[33]

Formation and expansion under Stalin

The Gulag was officially established on April 25, 1930 as the ULAG by the OGPU order 130/63 in accordance with the Sovnarkom order 22 p. 248 dated April 7, 1930. It was renamed as the Gulag in November of that year.[34]

The hypothesis that economic considerations were responsible for mass arrests during the period of Stalinism has been refuted on the grounds of former Soviet archives that have become accessible since the 1990s, although some archival sources also tend to support an economic hypothesis.[35][36] In any case, the development of the camp system followed economic lines. The growth of the camp system coincided with the peak of the Soviet industrialization campaign. Most of the camps established to accommodate the masses of incoming prisoners were assigned distinct economic tasks.[citation needed] These included the exploitation of natural resources and the colonization of remote areas, as well as the realization of enormous infrastructural facilities and industrial construction projects. The plan to achieve these goals with "special settlements" instead of labor camps was dropped after the revealing of the Nazino affair in 1933, subsequently the Gulag system was expanded.[citation needed]

The 1931–32 archives indicate the Gulag had approximately 200,000 prisoners in the camps; in 1935 — approximately 800,000 in camps and 300,000 in colonies (annual averages).[37]

In the early 1930s, a tightening of Soviet penal policy caused significant growth of the prison camp population.[citation needed] During the Great Purge of 1937–38, mass arrests caused another increase in inmate numbers. Hundreds of thousands of persons were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms on the grounds of one of the multiple passages of the notorious Article 58 of the Criminal Codes of the Union republics, which defined punishment for various forms of "counterrevolutionary activities." Under NKVD Order No. 00447, tens of thousands of Gulag inmates were executed in 1937–38 for "continuing counterrevolutionary activities".

Between 1934 and 1941, the number of prisoners with higher education increased more than eight times, and the number of prisoners with high education increased five times.[30] It resulted in their increased share in the overall composition of the camp prisoners.[30] Among the camp prisoners, the number and share of the intelligentsia was growing at the quickest pace.[30] Distrust, hostility, and even hatred for the intelligentsia was a common characteristic of the Soviet leaders.[30] Information regarding the imprisonment trends and consequences for the intelligentsia, derives from the extrapolations of Viktor Zemskov from a collection of prison camp population movements data.[30][38]

During World War II

| Mass repression in the Soviet Union |

|---|

| Economic repression |

| Political repression |

| Ideological repression |

| Ethnic repression |

Political role of the Gulag

On the eve of World War II, Soviet archives indicate a combined camp and colony population upwards of 1.6 million in 1939, according to V. P. Kozlov.[37] Anne Applebaum and Steven Rosefielde estimate that 1.2 to 1.5 million people were in Gulag system's prison camps and colonies when the war started.[39][40]

After the German invasion of Poland that marked the start of World War II in Europe, the Soviet Union invaded and annexed eastern parts of the Second Polish Republic. In 1940 the Soviet Union occupied Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Bessarabia (now the Republic of Moldova) and Bukovina. According to some estimates, hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens[41][42] and inhabitants of the other annexed lands, regardless of their ethnic origin, were arrested and sent to the Gulag camps. However, according to the official data, the total number of sentences for political and antistate (espionage, terrorism) crimes in USSR in 1939–41 was 211,106.[24]

Approximately 300,000 Polish prisoners of war were captured by the USSR during and after the 'Polish Defensive War'.[43] Almost all of the captured officers and a large number of ordinary soldiers were then murdered (see Katyn massacre) or sent to Gulag.[44] Of the 10,000-12,000 Poles sent to Kolyma in 1940–41, most prisoners of war, only 583 men survived, released in 1942 to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East.[45] Out of General Anders' 80,000 evacuees from Soviet Union gathered in Great Britain only 310 volunteered to return to Soviet-controlled Poland in 1947.[46]

During the Great Patriotic War, Gulag populations declined sharply due to a steep rise in mortality in 1942–43. In the winter of 1941 a quarter of the Gulag's population died of starvation.[47] 516,841 prisoners died in prison camps in 1941–43.[48][49]

In 1943, the term katorga works (каторжные работы) was reintroduced. They were initially intended for Nazi collaborators, but then other categories of political prisoners (for example, members of deported peoples who fled from exile) were also sentenced to "katorga works". Prisoners sentenced to "katorga works" were sent to Gulag prison camps with the most harsh regime and many of them perished.[49]

Economic role of the Gulag

Up until WWII, the Gulag system expanded dramatically to create a Soviet “camp economy”. Right before the war, forced labor provided 46.5% of the nation's nickel, 76% of its tin, 40% of its cobalt, 40.5% of its chrome-iron ore, 60% of its gold, and 25.3% of its timber.[50] And in preparation for war, the NKVD put up many more factories and built highways and railroads.

The Gulag quickly switched to production of arms and supplies for the army after the war began. At first, transportation remained a priority. In 1940, the NKVD focused most of its energy on railroad construction.[51] This would prove extremely important in the face of the German advance. In addition, factories converted to produce ammunition, uniforms, and other supplies. Moreover, the NKVD gathered skilled workers and specialists from throughout the Gulag into 380 special colonies which produced tanks, airplanes, armaments, and ammunition.[52]

Despite its cheapness, the camp economy suffered from serious flaws. For one, actual productivity almost never matched estimates, because the estimates were far too optimistic. In addition, scarcity of machinery and tools plagued the camps, and the tools that the camps did have quickly broke. The Eastern Siberian Trust of the Chief Administration of Camps for Highway Construction destroyed ninety-four trucks in just three years.[52] But the greatest problem was simple – forced labor is by nature less efficient than free labor. In fact, prisoners in the Gulag were, on average, half as productive as free laborers in the USSR at the time,[52] which may be explained by malnutrition.

To make up for this disparity, the NKVD worked prisoners harder than ever. To meet rising demand, prisoners worked longer and longer hours, and on lower food rations than ever before. A camp administrator said in a meeting, “There are cases when a prisoner is given only four or five hours out of twenty-four for rest, which significantly lowers his productivity.” Or, in the words of a former Gulag prisoner: “By the spring of 1942, the camp ceased to function. It was difficult to find people who were even able to gather firewood or bury the dead.”[52] The scarcity of food stemmed in part from the general strain on the entire Soviet Union, but also lack of central aid to the Gulag during the war. The central government focused all its attention on the military, and left the camps to their own defenses. In 1942 the Gulag set up the Supply Administration to find their own food and industrial goods. During this time, not only was food scarce, the NKVD limited rations in an attempt to motivate the prisoners to work harder for more food, a policy that lasted until 1948.[53]

In addition to food shortages, the Gulag suffered from labor scarcity in the beginning of the war. The Great Terror had provided a large supply of free labor, but by the start of WWII the purges had slowed down. In order to complete all of their projects, camp administrators moved prisoners from project to project.[51] To improve the situation, laws were implemented in mid-1940 that allowed short camp sentences (4 months or a year) to be given to those convicted of petty theft, hooliganism, or labor discipline infractions. By January 1941, the Gulag workforce had increased by approximately 300,000 prisoners.[51] But in 1942 the serious food shortages began, and camp populations dropped again. The camps lost still more prisoners to the war effort. Many laborers received early releases so that they could be drafted and sent to the front.[53]

Even as the pool of workers shrank, demand continued to grow rapidly. As a result, the Soviet government pushed the Gulag to “do more with less”. With less able-bodied workers and few supplies from outside the camp system, camp administrators had to find a way to maintain production. The solution they found was to push the remaining prisoners still harder. The NKVD employed a system of setting unrealistically high production goals, straining resources in an attempt to encourage higher productivity. Labor resources were further strained as the German armies pushed into Soviet territory, and many of the camps were forced to evacuate Western Russia. From the beginning of the war to halfway through 1944, 40 camps were created, and 69 were disbanded. In these evacuations, machinery received priority, leaving prisoners to reach safety on foot. Due to the speed of Operation Barbarossa’s advance, not all laborers could be evacuated in time, and many were massacred by the NKVD to prevent them from falling into German hands. While this practice denied the Germans a source of free labor, it also further restricted the Gulag’s capacity to keep up with the Red Army’s demands. When the tide of the war turned however, and the Soviets pushed the Germans back, the camps were replenished with fresh laborers. As the Red Army recaptured territories from the Germans, an influx of Soviet POW’s greatly increased the Gulag population.[53]

After World War II

After World War II the number of inmates in prison camps and colonies, again, rose sharply, reaching approximately 2.5 million people by the early 1950s (about 1.7 million of whom were in camps).

When the war in Europe ended in May 1945, as many as two million former Russian citizens were forcefully repatriated into the USSR.[54] On 11 February 1945, at the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the United States and United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the Soviet Union.[55] One interpretation of this agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Soviets. British and U.S. civilian authorities ordered their military forces in Europe to deport to the Soviet Union up to two million former residents of the Soviet Union, including persons who had left the Russian Empire and established different citizenship years before. The forced repatriation operations took place from 1945–47.[56]

Multiple sources state that Soviet POWs, on their return to the Soviet Union, were treated as traitors (see Order No. 270).[57][58][59] According to some sources, over 1.5 million surviving Red Army soldiers imprisoned by the Germans were sent to the Gulag.[60][61][62] However, that is a confusion with two other types of camps. During and after World War II, freed POWs went to special "filtration" camps. Of these, by 1944, more than 90 percent were cleared, and about 8 percent were arrested or condemned to penal battalions. In 1944, they were sent directly to reserve military formations to be cleared by the NKVD. Further, in 1945, about 100 filtration camps were set for repatriated Ostarbeiter, POWs, and other displaced persons, which processed more than 4,000,000 people. By 1946, the major part of the population of these camps were cleared by NKVD and either sent home or conscripted (see table for details).[63] 226,127 out of 1,539,475 POWs were transferred to the NKVD, i.e. the Gulag.[63][64]

| Results of the checks and the filtration of the repatriants (by 1 March 1946)[63] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Total | % | Civilian | % | POWs | % |

| Released and sent home (this figure included those who died in custody) | 2,427,906 | 57.81 | 2,146,126 | 80.68 | 281,780 | 18.31 |

| Conscripted | 801,152 | 19.08 | 141,962 | 5.34 | 659,190 | 42.82 |

| Sent to labour battalions of the Ministry of Defence | 608,095 | 14.48 | 263,647 | 9.91 | 344,448 | 22.37 |

| Sent to NKVD as spetskontingent (i.e. sent to GULAG) | 272,867 | 6.50 | 46,740 | 1.76 | 226,127 | 14.69 |

| Were waiting for transportation and worked for Soviet military units abroad | 89,468 | 2.13 | 61,538 | 2.31 | 27,930 | 1.81 |

| Totally: | 4,199,488 | 2,660,013 | 1,539,475 |

After Nazi Germany's defeat, ten NKVD-run "special camps" subordinate to the Gulag were set up in the Soviet Occupation Zone of post-war Germany. These "special camps" were former Stalags, prisons, or Nazi concentration camps such as Sachsenhausen (special camp number 7) and Buchenwald (special camp number 2). According to German government estimates "65,000 people died in those Soviet-run camps or in transportation to them."[65] According to German researchers, Sachsenhausen, where 12,500 Soviet era victims have been uncovered, should be seen as an integral part of the Gulag system.[66]

For years after World War II, a significant[citation needed] portion of the inmates were Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians from lands newly incorporated into the Soviet Union, as well as Finns, Poles, Volga Germans, Romanians and others.[citation needed] POWs, in contrast, were kept in a separate camp system (see POW labor in the Soviet Union), which was managed by GUPVI, a separate main administration with the NKVD/MVD.[citation needed]

Yet the major reason for the post-war increase in the number of prisoners was the tightening of legislation on property offences in summer 1947 (at this time there was a famine in some parts of the Soviet Union, claiming about 1 million lives), which resulted in hundreds of thousands of convictions to lengthy prison terms, sometimes on the basis of cases of petty theft or embezzlement. At the beginning of 1953 the total number of prisoners in prison camps was more than 2.4 million of which more than 465,000 were political prisoners.[49]

The state continued to maintain the extensive camp system for a while after Stalin's death in March 1953, although the period saw the grip of the camp authorities weaken, and a number of conflicts and uprisings occur (see Bitch Wars; Kengir uprising; Vorkuta uprising).

The amnesty in March 1953 was limited to non-political prisoners and for political prisoners sentenced to not more than 5 years, therefore mostly those convicted for common crimes were then freed. The release of political prisoners started in 1954 and became widespread, and also coupled with mass rehabilitations, after Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalinism in his Secret Speech at the 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956.

The Gulag institution was closed by the MVD order No 020 of 25 January 1960[34] but forced labor colonies for political and criminal prisoners continued to exist. Political prisoners continued to be kept in one of the most famous camps Perm-36[67] until 1987 when it was closed.[68] (See also Foreign forced labor in the Soviet Union)

The Russian penal system, despite reforms and a reduction in prison population, informally or formally continues many of practices endemic to the Gulag system, including forced labor, inmates policing inmates, and prisoner intimidation.[69]

Conditions

Living and working conditions in the camps varied significantly across time and place, depending, among other things, on the impact of broader events (World War II, countrywide famines and shortages, waves of terror, sudden influx or release of large numbers of prisoners). However, to one degree or another, the large majority of prisoners at most times faced meager food rations, inadequate clothing, overcrowding, poorly insulated housing, poor hygiene, and inadequate health care. Most prisoners were compelled to perform harsh physical labor.[70] In most periods and economic branches, the degree of mechanization of work processes was significantly lower than in the civilian industry: tools were often primitive and machinery, if existent, short in supply. Officially established work hours were in most periods longer and days off were fewer than for civilian workers. Often official work time regulations were extended by local camp administrators.[citation needed]

Andrei Vyshinsky, procurator of the Soviet Union, wrote a memorandum to NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov in 1938 which stated:

Among the prisoners there are some so ragged and liceridden that they pose a sanitary danger to the rest. These prisoners have deteriorated to the point of losing any resemblance to human beings. Lacking food . . . they collect orts [refuse] and, according to some prisoners, eat rats and dogs.[71]

In general, the central administrative bodies showed a discernible interest in maintaining the labor force of prisoners in a condition allowing the fulfillment of construction and production plans handed down from above. Besides a wide array of punishments for prisoners refusing to work (which, in practice, were sometimes applied to prisoners that were too enfeebled to meet production quota), they instituted a number of positive incentives intended to boost productivity. These included monetary bonuses (since the early 1930s) and wage payments (from 1950 onwards), cuts of individual sentences, general early-release schemes for norm fulfillment and overfulfillment (until 1939, again in selected camps from 1946 onwards), preferential treatment, and privileges for the most productive workers (shock workers or Stakhanovites in Soviet parlance).[72]

A distinctive incentive scheme that included both coercive and motivational elements and was applied universally in all camps consisted in standardized "nourishment scales": the size of the inmates’ ration depended on the percentage of the work quota delivered. Naftaly Frenkel is credited for the introduction of this policy. While it was effective in compelling many prisoners to work harder, for many a prisoner it had the adverse effect, accelerating the exhaustion and sometimes causing the death of persons unable to fulfill high production quota.[citation needed]

Immediately after the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 the conditions in camps worsened drastically: quotas were increased, rations cut, and medical supplies came close to none, all of which led to a sharp increase in mortality. The situation slowly improved in the final period and after the end of the war.

Considering the overall conditions and their influence on inmates, it is important to distinguish three major strata of Gulag inmates:

- "Kulaks", osadniks, "ukazniks" (people sentenced for violation of various ukases, such as Law of Spikelets, decree about work discipline, etc.), occasional violators of criminal law

- Dedicated criminals: "thieves in law"

- People sentenced for various political and religious reasons.

Mortality in Gulag camps in 1934–40 was 4–6 times higher than average in Russia. The estimated total number of those who died in imprisonment in 1930–53 is at least 1.76 million, about half of which occurred between 1941–43 following the German invasion.[73][74] If prisoner deaths from labor colonies and special settlements are included, the death toll rises to 2,749,163, although the historian who compiled this estimate (J. Otto Pohl) stresses that it is incomplete, and doesn't cover all prisoner categories for every year.[18][75] Other scholars have stressed that internal discrepancies in archival material suggests that the NKVD Gulag data are seriously incomplete.[19] Adam Jones wrote:

It was these Siberian camps, devoted either to gold-mining or timber harvesting, that inflicted the greatest toll in the Gulag system. Such camps “can only be described as extermination centres,” according to Leo Kuper. The camp network that came to symbolize the horrors of the Gulag was centered on the Kolyma gold-fields, where “outside work for prisoners was compulsory until the temperature reached −50C and the death rate among miners in the goldfields was estimated at about 30 percent per annum.[76]

Social conditions

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2014) |

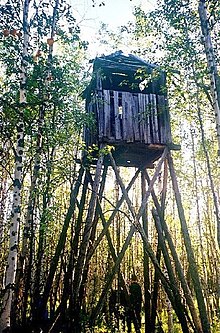

The convicts in such camps were actively involved in all kinds of labor with one of them being logging (lesopoval). The working territory of logging presented by itself a square and was surrounded by forest clearing. Thus, all attempts to exit or escape from it were well observed from the four towers set at each of its corners.

When investigating the shooting of these "escaping" prisoners, the position of the dead body was usually the only factor considered[citation needed]. That the body would lie with its feet to the camp and its head away from it was considered sufficient evidence of an escape attempt. As a result, it was common practice for the guards to simply adjust the position of the body after killing a "runner" to ensure that the killing would be declared justified.[citation needed] There is some evidence that money rewards were given to any guards who shot an escaping prisoner, but the official rules (as seen below) state guards were fined if they shot escaping prisoners.[citation needed]

Locals who captured a runaway were given rewards.[77] It is also said that Gulags in colder areas were less concerned with finding escaped prisoners as they would die anyhow from the severely cold winters. Prisoners who did escape without getting shot were often found dead kilometres away from the camp.

Geography

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2007) |

In the early days of Gulag, the locations for the camps were chosen primarily for the isolated conditions involved. Remote monasteries in particular were frequently reused as sites for new camps. The site on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea is one of the earliest and also most noteworthy, taking root soon after the Revolution in 1918.[3] The colloquial name for the islands, "Solovki", entered the vernacular as a synonym for the labor camp in general. It was presented to the world as an example of the new Soviet method for "re-education of class enemies" and reintegrating them through labor into Soviet society. Initially the inmates, largely Russian intelligentsia, enjoyed relative freedom (within the natural confinement of the islands). Local newspapers and magazines were published and even some scientific research was carried out (e.g., a local botanical garden was maintained but unfortunately later lost completely). Eventually Solovki turned into an ordinary Gulag camp; in fact some historians maintain that it was a pilot camp of this type. In 1929 Maxim Gorky visited the camp and published an apology for it. The report of Gorky’s trip to Solovki was included in the cycle of impressions titled “Po Soiuzu Sovetov,” Part V, subtitled “Solovki.” In the report, Gorky wrote that “camps such as ‘Solovki’ were absolutely necessary.”[78]

With the new emphasis on Gulag as the means of concentrating cheap labor, new camps were then constructed throughout the Soviet sphere of influence, wherever the economic task at hand dictated their existence (or was designed specifically to avail itself of them, such as the White Sea-Baltic Canal or the Baikal Amur Mainline), including facilities in big cities — parts of the famous Moscow Metro and the Moscow State University new campus were built by forced labor. Many more projects during the rapid industrialization of the 1930s, war-time and post-war periods were fulfilled on the backs of convicts. The activity of Gulag camps spanned a wide cross-section of Soviet industry.

The majority of Gulag camps were positioned in extremely remote areas of northeastern Siberia (the best known clusters are Sevvostlag (The North-East Camps) along Kolyma river and Norillag near Norilsk) and in the southeastern parts of the Soviet Union, mainly in the steppes of Kazakhstan (Luglag, Steplag, Peschanlag). A very precise map was made by the Memorial Foundation.[79] These were vast and sparsely inhabited regions with no roads (in fact, the construction of the roads themselves was assigned to the inmates of specialized railroad camps) or sources of food, but rich in minerals and other natural resources (such as timber). However, camps were generally spread throughout the entire Soviet Union, including the European parts of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. There were several camps outside the Soviet Union, in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Mongolia, which were under the direct control of the Gulag.

Not all camps were fortified; some in Siberia were marked only by posts. Escape was deterred by the harsh elements, as well as tracking dogs that were assigned to each camp. While during the 1920s and 1930s native tribes often aided escapees, many of the tribes were also victimized by escaped thieves. Tantalized by large rewards as well, they began aiding authorities in the capture of Gulag inmates. Camp guards were given stern incentive to keep their inmates in line at all costs; if a prisoner escaped under a guard's watch, the guard would often be stripped of his uniform and become a Gulag inmate himself.[citation needed] Further, if an escaping prisoner was shot, guards could be fined amounts that were often equivalent to one or two weeks wages.[citation needed]

In some cases, teams of inmates were dropped off in new territory with a limited supply of resources and left to set up a new camp or die. Sometimes it took several waves of colonists before any one group survived to establish the camp.[citation needed]

The area along the Indigirka river was known as the Gulag inside the Gulag. In 1926, the Oimiakon (Оймякон) village in this region registered the record low temperature of −71.2 °C (−96 °F).

Under the supervision of Lavrenty Beria who headed both NKVD and the Soviet atom bomb program until his demise in 1953, thousands of zeks were used to mine uranium ore and prepare test facilities on Novaya Zemlya, Vaygach Island, Semipalatinsk, among other sites.

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union, there were at least 476 separate camp administrations.[80][81] The Russian researcher Galina Ivanova stated that,

"to date, Russian historians have discovered and described 476 camps that existed at different times on the territory of the USSR. It is well known that practically every one of them had several branches, many of which were quite large. In addition to the large numbers of camps, there were no less than 2,000 colonies. It would be virtually impossible to reflect the entire mass of Gulag facilities on a map that would also account for the various times of their existence."[81]

Since many of these existed only for short periods, the number of camp administrations at any given point was lower. It peaked in the early 1950s, when there were more than 100 camp administrations across the Soviet Union. Most camp administrations oversaw several single camp units, some as many as dozens or even hundreds.[82] The infamous complexes were those at Kolyma, Norilsk, and Vorkuta, all in arctic or subarctic regions. However, prisoner mortality in Norilsk in most periods was actually lower than across the camp system as a whole.[83]

Special institutions

- Special camps or zones for children (Gulag jargon: ["малолетки", maloletki] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), underaged), for disabled (in Spassk), and for mothers (["мамки", mamki] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) with babies.

- Camps for "wives of traitors of Motherland" — there was a special category of repression: "Traitor of Motherland Family Member" ([ЧСИР, член семьи изменника Родины: ChSIR, Chlyen sem'i izmennika Rodini] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)).

- Sharashka (шарашка) were in fact secret research laboratories, where the arrested and convicted scientists, some of them prominent, were anonymously developing new technologies, and also conducting basic research.

Historiography

Archival documents

Statistical reports made by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD between the 1930s and 1950s are kept in the State Archive of the Russian Federation formerly called Central State Archive of the October Revolution (CSAOR). These documents were highly classified and inaccessible. Amid glasnost and democratization in the late 1980s, Viktor Zemskov and other Russian researchers managed to gain access to the documents and published the highly classified statistical data collected by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD and related to the number of the Gulag prisoners, special settlers, etc. In 1995, Zemskov wrote that foreign scientists have begun to be admitted to the restricted-access collection of these documents in the State Archive of the Russian Federation since 1992.[84] However, only one historian, namely Zemskov, was admitted to these archives, and later the archives were again “closed”, according to Leonid Lopatnikov.[85]

While considering the issue of reliability of the primary data provided by corrective labor institutions, it is necessary to take into account the following two circumstances. On the one hand, their administration was not interested to understate the number of prisoners in its reports, because it would have automatically led to a decrease in the food supply plan for camps, prisons, and corrective labor colonies. The decrement in food would have been accompanied by an increase in mortality that would have led to wrecking of the vast production program of the Gulag. On the other hand, overstatement of data of the number of prisoners also did not comply with departmental interests, because it was fraught with the same (i.e., impossible) increase in production tasks set by planning bodies. In those days, people were highly responsible for non-fulfilment of plan. It seems that a resultant of these objective departmental interests was a sufficient degree of reliability of the reports.[86]

Between 1990 and 1992, the first precise statistical data on the Gulag based on the Gulag archives were published by Viktor Zemskov.[87] These had been generally accepted by leading Western scholars,[12][17] despite the fact that a number of inconsistencies were found in this statistics.[88] It is also necessary to note that not all conclusion drawn by Zemskov based on his data had been generally accepted. Thus, Sergei Maksudov noted that although the literary sources, for example the books of Lev Razgon or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, did not envisage the total number of the camps very well and markedly exaggerated their size. On the other hand, Viktor Zemskov, who published many documents by the NKVD and KGB, is very far from understanding of the Gulag essence and the nature of socio-political processes in the country. Without distinguishing the degree of accuracy and reliability of certain figures, without making a critical analysis of sources, without comparing new data with already known information, Zemskov absolutizes the published materials by presenting them as the ultimate truth. As a result, his attempts to make generalized statements with reference to a particular document, as a rule, do not hold water.[89]

In response, Zemskov wrote that the charge that Zemskov allegedly did not compare new data with already known information could not be called fair. In his words, the trouble with most western writers is that they do not benefit from such comparisons. Zemskov added that when he tried not to overuse the juxtaposition of new information with “old” one, it was only because of a sense of delicacy, not to once again psychologically traumatize the researchers whose works used incorrect figures, as it turned out after the publication of the statistics by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD.[84]

According to French historian Nicolas Werth, the mountains of the materials of the Gulag archives, which are stored in funds of the State Archive of the Russian Federation and are being constantly exposed during the last fifteen years, represent only a very small part of bureaucratic prose of immense size left over the decades of “creativity” by the dull and reptile organization managing the Gulag. In many cases, local camp archives, which had been stored in sheds, barracks, or other rapidly disintegrating buildings, simply disappeared in the same way as most of the camp buildings did.[90]

In 2004 and 2005, some archival documents were published in the edition Istoriya Stalinskogo Gulaga. Konets 1920-kh — Pervaya Polovina 1950-kh Godov. Sobranie Dokumentov v 7 Tomakh (The History of Stalin’s Gulag. From the Late 1920s to the First Half of the 1950s. Collection of Documents in Seven Volumes) wherein each of its seven volumes covered a particular issue indicated in the title of the volume: the first volume has the title Massovye Repressii v SSSR (Mass Repression in the USSR),[91] the second volume has the title Karatelnaya Sistema. Struktura i Kadry (Punitive System. Structure and Cadres),[92] the third volume has the title Ekonomika Gulaga (Economy of the Gulag),[93] the forth volume has the title Naselenie Gulaga. Chislennost i Usloviya Soderzhaniya (The Population of the Gulag. The Number and Conditions of Confinement),[94] the fifth volume has the title Specpereselentsy v SSSR (Specsettlers in the USSR),[95] the sixth volume has the title Vosstaniya, Bunty i Zabastovki Zaklyuchyonnykh (Uprisings, Riots, and Strikes of Prisoners),[96] the seventh volume has the title Sovetskaya Pepressivno-karatelnaya Politika i Penitentsiarnaya Sistema. Annotirovanniy Ukazatel Del GA RF (Soviet Repressive and Punitive Policy. Annotated Index of Cases of the SA RF).[97] The edition contains the brief introductions by the two “patriarchs of the Gulag science”, Robert Conquest and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and 1431 documents, the overwhelming majority of which were obtained from funds of the State Archive of the Russian Federation.[98]

History of Gulag population estimates

During the decades before the dissolution of the USSR, the debates about the population size of GULAG failed to arrive at generally accepted figures; wide-ranging estimates have been offered,[99] and the bias toward higher or lower side was sometimes ascribed to political views of the particular author.[99] Some of those earlier estimates (both high and low) are shown in the table below. The final estimates of the Gulag population will be available only when all the Soviet archives will be opened.

| GULAG population | Year the estimate was made for | Source | Methodology | ||

| 15 million | 1940-42 | Mora & Zwiernag (1945)[100] | -- | ||

| 2.3 million | December 1937 | Timasheff (1948)[101] | Calculation of disenfranchised population | ||

| Up to 3.5 million | 1941 | Jasny (1951)[102] | Analysis of the output of the Soviet enterprises run by NKVD | ||

| 50 million | total number of persons passed through GULAG |

Solzhenitsyn (1975)[103] | Analysis of various indirect data, including own experience and testimonies of numerous witnesses | ||

| 16 million | 1938 | Antonov-Ovseenko (1980)[104] | This author confused monthly average with annual figures thereby producing estimates 12 times too high.[105] | ||

| 4-5 million | 1939 | Wheatcroft (1981)[106] | Analysis of demographic data.a | ||

| 10.6 million | 1941 | Rosefielde (1981)[107] | Based on data of Mora & Zwiernak and annual mortality.a | ||

| 5.5-9.5 million | late 1938 | Conquest (1991)[108] | 1937 Census figures, arrest and deaths estimates, variety of personal and literary sources.a | ||

| 4-5 million | every single year | Volkogonov (1990s)[109] | |||

| a.^ Note: Later numbers from Rosefielde, Wheatcroft and Conquest were revised down by the authors themselves.[12][39] | |||||

Political reforms in the USSR in late 1980s ("glastnost'") and subsequent dissolution of the USSR had led to release of a large amount of formerly classified archival documents,[110] including new demographic and NKVD data.[17] Analysis of the official GULAG statistics by Western scholars immediately demonstrated that, despite their inconsistency, they do not support previously published higher estimates.[99] Importantly, the released documents made possible to clarify terminology used to describe different categories of forced labour population, because the use of the terms "forced labour", "GULAG", "camps" interchangeably by early researchers led to significant confusion and resulted in significant inconsistencies in the earlier estimates.[99] Archival studies revealed several components of the NKVD penal system in the Stalinist USSR: prisons, labor camps, labor colonies, as well as various "settlements" (exile) and of non-custodial forced labour.[6] Although most of them fit the definition of forced labour, only labour camps, and labour colonies were associated with punitive forced labour in detention.[6] Forced labour camps ("GULAG camps") were hard regime camps, whose inmates were serving more than three-year terms. As a rule, they were situated in remote parts of the USSR, and labour conditions were extremely hard there. They formed a core of the GULAG system. The inmates of "corrective labour colonies" served shorter terms; these colonies were located in less remote parts of the USSR, and they were run by local NKVD administration.[6] Preliminary analysis of the GULAG camps and colonies statistics (see the chart on the right) demonstrated that the population reached the maximum before the World War II, then dropped sharply, partially due to massive releases, partially due to wartime high mortality, and then was gradually increasing until the end of Stalin era, reaching the global maximum in 1953, when the combined population of GULAG camps and labour colonies amounted to 2,625,000.[111]

The results of these archival studies convinced many scholars, including Robert Conquest[12] or Stephen Wheatcroft to reconsider their earlier estimates of the size of the GULAG population, although the 'high numbers' of arrested and deaths are not radically different from earlier estimates.[12] Although such scholars as Rosefielde or Vishnevsky point at several inconsistencies in archival data,[88] it is generally believed that these data provide more reliable and detailed information that the indirect data and literary sources available for the scholars during the Cold War era.[17]

These data allowed scholars to conclude that during the period of 1928–53, about 14 million prisoners passed through the system of GULAG labour camps and 4-5 million passed through the labour colonies.[12] Thus, these figures reflect the number of convicted persons, and do not take into account the fact that a significant part of Gulag inmates had been convicted more than one time, so the actual number of convicted is somewhat overstated by these statistics.[17] From other hand, during some periods of Gulag history the official figures of GULAG population reflected the camps' capacity, not the actual amount of inmates, so the actual figures were 15% higher in, e.g. 1946.[12]

Influence

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

Culture

The Gulag spanned nearly four decades of Soviet and East European history and affected millions of individuals. Its cultural impact was enormous.

The Gulag has become a major influence on contemporary Russian thinking, and an important part of modern Russian folklore. Many songs by the authors-performers known as the bards, most notably Vladimir Vysotsky and Alexander Galich, neither of whom ever served time in the camps, describe life inside the Gulag and glorified the life of "Zeks". Words and phrases which originated in the labor camps became part of the Russian/Soviet vernacular in the 1960s and 1970s.

The memoirs of Alexander Dolgun, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Varlam Shalamov and Yevgenia Ginzburg, among others, became a symbol of defiance in Soviet society. These writings, particularly those of Solzhenitsyn, harshly chastised the Soviet people for their tolerance and apathy regarding the Gulag, but at the same time provided a testament to the courage and resolve of those who were imprisoned.

Another cultural phenomenon in the Soviet Union linked with the Gulag was the forced migration of many artists and other people of culture to Siberia. This resulted in a Renaissance of sorts in places like Magadan, where, for example, the quality of theatre production was comparable to Moscow's.

Literature

Many eyewitness accounts of Gulag prisoners have been published:

- Varlam Shalamov's Kolyma Tales is a short-story collection, cited by most major works on the Gulag, and widely considered one of the main Soviet accounts.

- Victor Kravchenko wrote I Chose Freedom after defecting to the United States in 1944. As a leader of industrial plants he had encountered forced labor camps in across the Soviet Union from 1935 to 1941. He describes a visit to one camp at Kemerovo on the Tom River in Siberia. Factories paid a fixed sum to the KGB for every convict they employed.

- Anatoli Granovsky wrote I Was an NKVD Agent after defecting to Sweden in 1946 and included his experiences seeing gulag prisoners as a young boy, as well as his experiences as a prisoner himself in 1939. Granovsky's father was sent to the gulag in 1937.

- Julius Margolin's book A Travel to the Land Ze-Ka was finished in 1947, but it was impossible to publish such a book about the Soviet Union at the time, immediately after World War II.

- Gustaw Herling-Grudziński wrote A World Apart, which was translated into English by Andrzej Ciolkosz and published with an introduction by Bertrand Russell in 1951. By describing life in the gulag in a harrowing personal account, it provides an in-depth, original analysis of the nature of the Soviet communist system.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's book The Gulag Archipelago was not the first literary work about labor camps. His previous book on the subject, "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich", about a typical day of the Gulag inmate, was originally published in the most prestigious Soviet monthly, Novy Mir (New World), in November 1962, but was soon banned and withdrawn from all libraries. It was the first work to demonstrate the Gulag as an instrument of governmental repression against its own citizens on a massive scale. The First Circle, an account of three days in the lives of prisoners in the Marfino sharashka or special prison was submitted for publication to the Soviet authorities shortly after One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich but was rejected and later published abroad in 1968.

- János Rózsás, Hungarian writer, often referred to as the Hungarian Solzhenitsyn, wrote many books and articles on the issue of the Gulag.

- Zoltan Szalkai, Hungarian documentary filmmaker made several films of gulag camps.

- Karlo Štajner, a Croatian communist active in the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia and manager of Comintern Publishing House in Moscow 1932–39, was arrested one night and taken from his Moscow home under accusation of anti-revolutionary activities. He spent the following 20 years in camps from Solovki to Norilsk. After USSR–Yugoslavian political normalization he was re-tried and quickly found innocent. He left the Soviet Union with his wife, who had been waiting for him for 20 years, in 1956 and spent the rest of his life in Zagreb, Croatia. He wrote an impressive book titled 7000 days in Siberia.

- Dancing Under the Red Star by Karl Tobien (ISBN 1-4000-7078-3) tells the story of Margaret Werner, an athletic girl who moves to Russia right before the start of Stalin's terror. She faces many hardships, as her father is taken away from her and imprisoned. Werner is the only American woman who survived the Gulag to tell about it.

- Alexander Dolgun's Story: An American in the Gulag (ISBN 0-394-49497-0), by a member of the US Embassy, and I Was a Slave in Russia (ISBN 0-815-95800-5), an American factory owner's son, were two more American citizens interned who wrote of their ordeal. They were interned due to their American citizenship for about eight years c. 1946–55.

- Yevgenia Ginzburg wrote two famous books of her remembrances, Journey Into the Whirlwind and Within the Whirlwind.

- Savić Marković Štedimlija, pro-Croatian Montenegrin ideologist and Ustasha regime collaborator. Caught on the run in Austria by the Red Army in 1945, he was sent to the USSR and spent ten years in Gulag. After release, Marković wrote autobiographic account in two volumes titled Ten years in Gulag (Deset godina u Gulagu, Matica crnogorska, Podgorica, Montenegro 2004).

- Sławomir Rawicz's book, The Long Walk is a controversial account of his escape from the gulag during World War II.

- Anița Nandriș-Cudla's book, 20 Years in Siberia [20 de ani în Siberia] is the own life's account written by a Romanian peasant woman from Bucovina (Mahala village near Cernăuți) who managed to survive the harsh, forced labour system together with her three sons. Together with her husband and the three under aged children, she was deported from Mahala village to the Soviet Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, at the Polar Circle, with no trial or even communicated accusation. The same night of 12th to 13 June 1941, (that is before the breakout of the Second World War), overall 602 fellow villagers were arrested and deported, without any prior notice. Her mother had the same sentence but was spared from deportation after the fact she was paraplegic was acknowledged by authorities. As later discovered, the reason for deportation and forced labour was the fake and nonsensical heads that, allegedly, her husband had been mayor in the Romanian administration, politician and rich peasant, none of the later being at least true. Separated from her husband, she brought up the three boys, overcame typhus, scorbutus, malnutrition, extreme cold and harsh toils, to later return to Bucovina after rehabilitation. Her manuscript was written toward the end of her life, in the simple and direct language of a peasant with 3 years of school education, and was secretly brought to Romania before the fall of Romanian communism, in 1982. Her manuscript was first published in 1991. Deportation was shared mainly with Romanians from Bucovina and Basarabia, Finnish and Polish prisoners, as token that Gulag labour camps had also been used for shattering/ extermination of the natives in the newly occupied territories of the Soviet Union.

Movies and television

- GULAG 113 (documentary)

- As Far as My Feet Will Carry Me

- Gulag (1985), U.S. Showtime film

- I Am David (2003 U.S., 2004 U.K.)

- The Edge (2010)

- Lost in Siberia

- One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

- My Way (2001)

- The Way Back

- Agapitova and the rescued onesdocumentary film by Dzintra Geka (2009)

- Within the Whirlwind (2009)

Colonization

Soviet state documents show that the goals of the gulag included colonization of sparsely populated remote areas. To this end, the notion of "free settlement" was introduced.

When well-behaved persons had served the majority of their terms, they could be released for "free settlement" (вольное поселение, volnoye poseleniye) outside the confinement of the camp. They were known as "free settlers" (вольнопоселенцы, volnoposelentsy, not to be confused with the term ссыльнопоселенцы,ssyl'noposelentsy, "exile settlers"). In addition, for persons who served full term, but who were denied the free choice of place of residence, it was recommended to assign them for "free settlement" and give them land in the general vicinity of the place of confinement.

The gulag inherited this approach from the katorga system.

It is estimated that of the 40,000 people collecting state pensions in Vorkuta, 32,000 are trapped former gulag inmates, or their descendants.[113]

Life after term served

Persons who served a term in a camp or in a prison were restricted from taking a wide range of jobs. Concealment of a previous imprisonment was a triable offence. Persons who served terms as "politicals" were nuisances for "First Departments" ([Первый Отдел, Pervyj Otdel] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), outlets of the secret police at all enterprises and institutions), because former "politicals" had to be monitored.

Many people released from camps were restricted from settling in larger cities.

Gulag memorials

Both Moscow and St. Petersburg have memorials to the victims of the Gulag made of boulders from the Solovki camp — the first prison camp in the Gulag system. Moscow's memorial is on Lubyanka Square, the site of the headquarters of the NKVD. People gather at these memorials every year on the Day of Victims of the Repression (October 30).

Gulag Museum

Moscow has the State Gulag Museum whose first director was Anton Antonov-Ovseyenko.[114][115][116][117]

See also

- 101st kilometre

- Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code)

- Federal Prisons System of the Russian Federation

- Gulag detainees

- Forced settlements in the Soviet Union

- Mass graves in the Soviet Union

- Memorial Society

- Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

- Political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union

- Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–41)

- Forced labor camps elsewhere

- Danube-Black Sea Canal (Communist Romania)

- Devil's Island (France)

- Extermination through labor (Nazi Germany)

- Goli otok (Yugoslavia)

- Hoeryong concentration camp (North Korea)

- Katorga (Russian Empire)

- Laogai (China)

- Nazi concentration camp

- Reeducation camp (Vietnam)

- Spaç Prison (Albania)

- The Vietnamese Gulag

- Yodok concentration camp (North Korea)

References

- ^ Other Soviet penal labor systems not formally included in GULag were: (a) camps for the prisoners of war captured by the Soviet Union, administered by GUPVI (b) filtration camps created during World War II for temporary detention of Soviet Ostarbeiters and prisoners of war while they were being screened by the security organs in order to "filter out" the black sheep, (c) "special settlements" for internal exiles including "kulaks" and deported ethnic minorities, such as Volga Germans, Poles, Balts, Caucasians, Crimean Tartars, and others. During certain periods of Soviet history, each of these camp systems held millions of people. Many hundreds of thousand were also sentenced to forced labor without imprisonment at their normal place of work. (Applebaum, pages 579-580)

- ^ G. Zheleznov, Vinogradov, F. Belinskii (1926-12-14). "Letter To the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik)". Retrieved 2015-04-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Doubleday. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1 Cite error: The named reference "Applebaum 2003" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev. A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-300-08760-8 p. 15

- ^ Steven Rosefielde. Red Holocaust. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0-415-77757-7 pg. 247: "They served as killing fields during much of the Stalin period, and as a vast pool of cheap labor for state projects."

- ^ a b c d e f g Getty, Rittersporn, Zemskov. Victims of the Soviet Penal System in the Pre-War Years: A First Approach on the Basis of Archival Evidence. The American Historical Review, Vol. 98, No. 4 (Oct., 1993), pp. 1017-1049

- ^ "Gulag: a History of the Soviet Camps". Arlindo-correia.org. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ Stephen Wheatcroft. "The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930-45", Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 48, No. 8 (Dec., 1996), pp. 1319-1353

- ^ Norman Davies. "Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory" (2006), pp. 328-329

- ^ Archived 2008-12-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Демографические потери от репрессий". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robert Conquest in "Victims of Stalinism: A Comment." Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 49, No. 7 (Nov., 1997), pp. 1317-1319 states: "We are all inclined to accept the Zemskov totals (even if not as complete) with their 14 million intake to Gulag 'camps' alone, to which must be added 4-5 million going to Gulag 'colonies', to say nothing of the 3.5 million already in, or sent to, 'labor settlements'. However taken, these are surely 'high' figures." There are reservations to be made. For example, we now learn that the Gulag reported totals were of capacity rather than actual counts,leading to an underestimate in 1946 of around 15%. Then as to the numbers 'freed': there is no reason to accept the category simply because the MVD so listed them, and, in fact, we are told of 1947 (when the anecdotal evidence is of almost no one released) that this category concealed deaths: 100000 in the first quarter of the year'

- ^ "Repressions". Publicist.n1.by. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "H-Net Reviews".

- ^ http://www.memo.ru/HISTORY/POLAcy/g_3.htm

- ^ MVD of Russia: An Encyclopedia (МВД России: энциклопедия), 2002, ISBN 5-224-03722-0, p.541

- ^ a b c d e Michael Ellman. Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 54, No. 7 (Nov., 2002), pp. 1151-1172

- ^ a b Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Doubleday. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1 pg 583: "both archives and memoirs indicate that it was common practice in many camps to release prisoners who were on the point of dying, thereby lowering camp death statistics."

- ^ a b Steven Rosefielde. Red Holocaust. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0-415-77757-7 pg. 67 "...more complete archival data increases camp deaths by 19.4 percent to 1,258,537"; pg 77: "The best archivally based estimate of Gulag excess deaths at present is 1.6 million from 1929 to 1953."

- ^ Robert Conquest, Preface, The Great Terror: A Reassessment: 40th Anniversary Edition, Oxford University Press, USA, 2007. p. xvi

- ^ "Repressions". Publicist.n1.by. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "What Were Their Crimes?". Gulaghistory.org. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ Uschan, M. Political Leaders. Lucent Books. 2002.

- ^ a b "Repressions". Publicist.n1.by. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ News Release: Forced labor camp artifacts from Soviet era on display at NWTC[dead link]

- ^ Anne Applebaum. "GULAG: a history". Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ "The Hidden Gulag – Exposing North Korea's Prison Camps" (PDF). The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- ^ Antony Barnett (2004-02-01). "Revealed: the gas chamber horror of North Korea's gulag". London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Земсков, Виктор (1991). "ГУЛАГ (историко-социологический аспект)". Социологические исследования (№ 6, 7). Retrieved 14 August 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ "'Gulag': The Other Killing Machine". The New York Times. May 11, 2003.

- ^ D.J. Dallin and B.I. Nicolayesky, Forced Labor in Soviet Russia, London 1948, p. 153.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (2): 1151–1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b Memorial http://www.memo.ru/history/NKVD/GULAG/r1/r1-4.htm

- ^ See, e.g. Michael Jakobson, Origins of the GULag: The Soviet Prison Camp System 1917–34, Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1993, p. 88.

- ^ See, e.g. Galina M. Ivanova, Labor Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Totalitarian System, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000, Chapter 2.

- ^ a b See for example Istorija stalinskogo Gulaga: konec 1920-kh - pervaia polovina 1950-kh godov; sobranie dokumentov v 7 tomakh, ed. by V. P. Kozlov et al., Moskva: ROSSPEN 2004, vol. 4: Naselenie Gulaga

- ^ "Таблица 3. Движение лагерного населения ГУЛАГа".

- ^ a b Rosefielde, Steven. The Russian economy: from Lenin to Putin.

- ^ Applebaum, Anne. Gulag: a history.

- ^ Franciszek Proch, Poland's Way of the Cross, New York 1987 P.146

- ^ "Project In Posterum". Project In Posterum. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- ^ Encyklopedia PWN 'KAMPANIA WRZEŚNIOWA 1939', last retrieved on 10 December 2005, Polish language

- ^ Template:En icon Marek Jan Chodakiewicz (2004). Between Nazis and Soviets: Occupation Politics in Poland, 1939–1947. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0484-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ beanbean (2008-05-02). "A Polish life. 5: Starobielsk and the trans-Siberian railway". My Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2012-05-08.

- ^ Hope, Michael. "Polish deportees in the Soviet Union". Wajszczuk.v.pl. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ GULAG: a History, Anne Applebaum

- ^ Zemskov, Gulag, Sociologičeskije issledovanija, 1991, No. 6, pp. 14-15.

- ^ a b c "Repressions". Publicist.n1.by. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ Ivanova, Galina Mikhailovna (2000). Labor Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Soviet Totalitarian System. Armonk, NY: Sharpe. pp. 69–126.

- ^ a b c Khevniuk, Oleg V. (2004). The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror. Yale University Press. pp. 236–286.

- ^ a b c d Ivanova, Galina Mikhailovna (2000). Labor Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Soviet Totalitarian System. Armonk, NY: Sharpe. pp. 69–126.

- ^ a b c Bacon, Edwin (1994). The Gulag at War: Stalin's Forced Labour System in the Light of the Archives. New York, NY: New York University Press. pp. 42–63, 82–100, 123–144.

- ^ Mark Elliott. "The United States and Forced Repatriation of Soviet Citizens, 1944-47," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 88, No. 2 (June, 1973), pp. 253-275.

- ^ "Repatriation - The Dark Side of World War II". Fff.org. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Forced Repatriation to the Soviet Union: The Secret Betrayal". Hillsdale.edu. 1939-09-01. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "The warlords: Joseph Stalin". Channel4.com. 1953-03-06. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Remembrance (Zeithain Memorial Grove)". Stsg.de. 1941-08-16. Retrieved 2009-01-06. [dead link]

- ^ "Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II". Historynet.com. 1941-09-08. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Sorting Pieces of the Russian Past". Hoover.org. 2002-10-23. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Patriots ignore greatest brutality". Smh.com.au. 2007-08-13. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Joseph Stalin killer file". Moreorless.au.com. 2001-05-23. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b c Земсков В.Н. К вопросу о репатриации советских граждан. 1944-1951 годы // История СССР. 1990. № 4 (Zemskov V.N. On repatriation of Soviet citizens. Istoriya SSSR., 1990, No.4

- ^ (“Военно-исторический журнал” (“Military-Historical Magazine”), 1997, №5. page 32)

- ^ Germans Find Mass Graves at an Ex-Soviet Camp New York Times, September 24, 1992

- ^ Ex-Death Camp Tells Story Of Nazi and Soviet Horrors New York Times, December 17, 2001

- ^ "The museum of history of political repressions "Perm-36"".

- ^ "Gulag revisited: Barbed memories". Russia Today. 2012.

- ^ "Slave labour and criminal cultures". The Economist. 2013-10-19.

- ^ The Gulag Collection: Paintings of Nikolai Getman[dead link]

- ^ Jonathan Brent. Inside the Stalin Archives: Discovering the New Russia. Atlas & Co., 2008 (ISBN 0977743330) pg. 12 Introduction online (PDF file)

- ^ Leonid Borodkin and Simon Ertz 'Forced Labor and the Need for Motivation: Wages and Bonuses in the Stalinist Camp System', Comparative Economic Studies, June 2005, Vol.47, Iss. 2, pp. 418–436.

- ^ "Demographic Losses Due to Repressions", by Anatoly Vishnevsky, Director of the Center for Human Demography and Ecology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Template:Ru icon

- ^ "The History of the GULAG", by Oleg V. Khlevniuk

- ^ Pohl, The Stalinist Penal System, p. 131.

- ^ Adam Jones (2010). "Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction". Taylor & Francis. p.195. ISBN 0-415-48618-1

- ^ "Nikolai Getman: The Gulag Collection"

- ^ Yedlin, Tova (1999). Maxim Gorky: A Political Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 188. ISBN 0-275-96605-4.

- ^ Map of Gulag, made by the Memorial Foundation on: [2].

- ^ "Система исправительно-трудовых лагерей в СССР". Memo.ru. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b Ivanova, Galina; Flath, Carol; Raleigh, Donald (2000). Labor Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Soviet Totalitarian System. London: M.E. Sharpe. p. 188. ISBN 0-7656-0426-4.

- ^ Anne Applebaum — Inside the Gulag[dead link]

- ^ "Coercion versus Motivation: Forced Labor in Norilsk" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b Земсков, Виктор (1995). "К вопросу о масштабах репрессий в СССР". Социологические исследования (№ 9): 118–127. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Лопатников, Леонид (2009). "К дискуссиям о статистике "Большого террора"". Вестник Европы (№ 26–27). Retrieved 20 August 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Земсков, Виктор (1994). "Политические репрессии в СССР (1917–1990 гг.)" (PDF). Россия XXI (№ 1–2): 107–124. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Rousso, Henry; Golsan, Richard (2004). Stalinism and nazism: history and memory compared. U of Nebraska Press. p. 92. ISBN 0-8032-9000-4.

- ^ a b Vishnevsky, Alantoly. Демографические потери от репрессий (The Demographic Loss of Repression), Demoscope Weekly, December 31, 2007, retrieved 13 Apr 2011

- ^ ��аксудов, Сергей (1995). "О публикациях в журнале "Социс"". Социологические исследования (№ 9): 114–118. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help); replacement character in|last=at position 1 (help) - ^ Werth, Nicolas (June 2007). "Der Gulag im Prisma der Archive. Zugänge, Erkenntnisse, Ergebnisse" (PDF). Osteuropa. 57 (6): 9–30.

- ^ История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х — первая половина 1950-х годов. Собрание документов в 7 томах. Том 1. Москва: Российская политическая энциклопедия. 2004. ISBN 5-8243-0605-2.

- ^ История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х — первая половина 1950-х годов. Собрание документов в 7 томах. Том 2. Карательная система. Структура и кадры. Москва: Российская политическая энциклопедия. 2004. ISBN 5-8243-0606-0.

- ^ История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х — первая половина 1950-х годов. Собрание документов в 7 томах. Том 3. Экономика Гулага. Москва: Российская политическая энциклопедия. 2004. ISBN 5-8243-0607-9.

- ^ История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х — первая половина 1950-х годов. Собрание документов в 7 томах. Том 4. Население Гулага. Численность и условия содержания. Москва: Российская политическая энциклопедия. 2004. ISBN 5-8243-0608-7.

- ^ История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х — первая половина 1950-х годов. Собрание документов в 7 томах. Том 5. Спецпереселенцы в СССР. Москва: Российская политическая энциклопедия. 2004. ISBN 978-5-8243-0608-8.

- ^ История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х — первая половина 1950-х годов. Собрание документов в 7 томах. Том 6. Восстания, бунты и забастовки заключенных. Москва: Российская политическая энциклопедия. 2004. ISBN 5-8243-0610-9.

- ^ История сталинского Гулага. Конец 1920-х — первая половина 1950-х годов. Собрание документов в 7 томах. Том 7. Советская репрессивно-карательная политика и пенитенциарная система. Аннотированный указатель дел ГА РФ. Москва: Российская политическая энциклопедия. 2005. ISBN 978-5-8243-0611-8.

- ^ Полян, Павел (2006). "Новые карты архипелага ГУЛАГ". Неприкосновенный запас (№2 (46)): 277–286. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d Edwin Bacon. Glasnost' and the Gulag: New Information on Soviet Forced Labour around World War II. Soviet Studies, Vol. 44, No. 6 (1992), pp. 1069-1086

- ^ Cited in David Dallin and Boris Nicolaevsky, Forced Labor in Soviet Russia. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1947), p. 59-62.

- ^ N. S. Timasheff. The Postwar Population of the Soviet Union. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 54, No. 2 (Sep., 1948), pp. 148-155

- ^ Naum Jasny. Labor and Output in Soviet Concentration Camps. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 59, No. 5 (Oct., 1951), pp. 405-419

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, A. The Gulag Archipelago Two, Harper and Row, 1975. Estimate was through 1953.

- ^ Anton Antonov-Ovseenko, Portret tirana (New York: Khronika, 1980), p. 387

- ^ Michael Ellman. Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 54, No. 7 (Nov., 2002), pp. 1151-1172)

- ^ S. G. Wheatcroft. On Assessing the Size of Forced Concentration Camp Labour in the Soviet Union, 1929-56. Soviet Studies, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Apr., 1981), pp. 265-295

- ^ Steven Rosefielde. An Assessment of the Sources and Uses of Gulag Forced Labour 1929-56. Soviet Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Jan., 1981), pp. 51-87

- ^ Robert Conquest. Excess Deaths and Camp Numbers: Some Comments. Soviet Studies, Vol. 43, No. 5 (1991), pp. 949-952

- ^ Rappaport, H. Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO Greenwood. 1999.

- ^ Andrea Graziosi. The New Soviet Archival Sources. Hypotheses for a Critical Assessment. Cahiers du Monde russe, Vol. 40, No. 1/2, Archives et nouvelles sources de l'histoiresoviétique, une réévaluation / Assessing the New Soviet Archival Sources (Jan. - Jun., 1999),pp. 13-63

- ^ "The Total Number of Repressed", by Anatoly Vishnevsky, Director of the Center for Human Demography and Ecology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Nikolai Getman: The Gulag Collection". The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ^ Robert Conquest, Paul Hollander: Political violence: belief, behavior, and legitimation p.55, Palgrave Macmillan;(2008) ISBN 978-0-230-60646-3

- ^ Гальперович, Данила (27 June 2010). "Директор Государственного музея ГУЛАГа Антон Владимирович Антонов-Овсеенко". Radio Liberty. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Banerji, Arup (2008). Writing history in the Soviet Union: making the past work. Berghahn Books. p. 271. ISBN 81-87358-37-8.

- ^ "About State Gulag Museum". The State Gulag Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Gulag - Museum on Communism".