Equivalence partitioning: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Cn}} |

|||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

==Limitations== |

==Limitations== |

||

In cases where the data ranges or sets involved approach simplicity (Example |

In cases where the data ranges or sets involved approach simplicity (Example: 0-4, 5-8, 9-12), and testing all values would be practical, blanket test coverage using all values within and bordering the ranges should be considered. Blanket test coverage can reveal bugs that would not be caught using the equivalence partitioning method, if the software includes sub-partitions which are unknown to the tester.{{cn|date=November 2015}} Also, in simplistic cases, the benefit of reducing the number of test values by using equivalence partitioning is diminished, in comparison to cases involving larger ranges (Example: 0-2000, 2001-3000, 3001-4000). |

||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

Revision as of 17:32, 24 November 2015

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

Equivalence partitioning (also called Equivalence Class Partitioning or ECP[1]) is a software testing technique that divides the input data of a software unit into partitions of equivalent data from which test cases can be derived. In principle, test cases are designed to cover each partition at least once. This technique tries to define test cases that uncover classes of errors, thereby reducing the total number of test cases that must be developed. An advantage of this approach is reduction in the time required for testing a software due to lesser number of test cases.

Equivalence partitioning is typically applied to the inputs of a tested component, but may be applied to the outputs in rare cases. The equivalence partitions are usually derived from the requirements specification for input attributes that influence the processing of the test object.

The fundamental concept of ECP comes from equivalence class which in turn comes from equivalence relation. A software system is in effect a computable function implemented as an algorithm in some implementation programming language. Given an input test vector some instructions of that algorithm get covered, ( see code coverage for details ) others do not. This gives the interesting relationship between input test vectors:- is an equivalence relation between test vectors if and only if the coverage foot print of the vectors are exactly the same, that is, they cover the same instructions, at same step. This would evidently mean that the relation cover would partition the input vector space of the test vector into multiple equivalence class. This partitioning is called equivalence class partitioning of test input. If there are equivalent classes, only vectors are sufficient to fully cover the system.

The demonstration can be done using a function written in C:

int safe_add( int a, int b )

{

int c = a + b;

if ( a >= 0 && b >= 0 && c < 0 )

{

fprintf ( stderr, "Overflow!\n" );

}

if ( a < 0 && b < 0 && c >= 0 )

{

fprintf ( stderr, "Underflow!\n" );

}

return c;

}

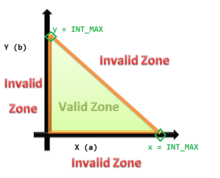

On the basis of the code, the input vectors of are partitioned. The blocks we need to cover are the overflow statement and the underflow statement and neither of these 2. That gives rise to 3 equivalent classes, from the code review itself.

To solve the input problem, we take refuge in the inequation

we note that there is a fixed size of Integer (computer science) hence, the z can be replaced with:-

and

with and

The values of the test vector at the strict condition of the equality that is and are called the boundary values, Boundary-value analysis has detailed information about it. Note that the graph only covers the overflow case, first quadrant for X and Y positive values.

In general an input has certain ranges which are valid and other ranges which are invalid. Invalid data here does not mean that the data is incorrect, it means that this data lies outside of specific partition. This may be best explained by the example of a function which takes a parameter "month". The valid range for the month is 1 to 12, representing January to December. This valid range is called a partition. In this example there are two further partitions of invalid ranges. The first invalid partition would be <= 0 and the second invalid partition would be >= 13.

... -2 -1 0 1 .............. 12 13 14 15 .....

--------------|-------------------|---------------------

invalid partition 1 valid partition invalid partition 2

The testing theory related to equivalence partitioning says that only one test case of each partition is needed to evaluate the behaviour of the program for the related partition. In other words it is sufficient to select one test case out of each partition to check the behaviour of the program. To use more or even all test cases of a partition will not find new faults in the program. The values within one partition are considered to be "equivalent". Thus the number of test cases can be reduced considerably.

An additional effect of applying this technique is that you also find the so-called "dirty" test cases. An inexperienced tester may be tempted to use as test cases the input data 1 to 12 for the month and forget to select some out of the invalid partitions. This would lead to a huge number of unnecessary test cases on the one hand, and a lack of test cases for the dirty ranges on the other hand.

The tendency is to relate equivalence partitioning to so called black box testing which is strictly checking a software component at its interface, without consideration of internal structures of the software. But having a closer look at the subject there are cases where it applies to grey box testing as well. Imagine an interface to a component which has a valid range between 1 and 12 like the example above. However internally the function may have a differentiation of values between 1 and 6 and the values between 7 and 12. Depending upon the input value the software internally will run through different paths to perform slightly different actions. Regarding the input and output interfaces to the component this difference will not be noticed, however in your grey-box testing you would like to make sure that both paths are examined. To achieve this it is necessary to introduce additional equivalence partitions which would not be needed for black-box testing. For this example this would be:

... -2 -1 0 1 ..... 6 7 ..... 12 13 14 15 .....

--------------|---------|----------|---------------------

invalid partition 1 P1 P2 invalid partition 2

valid partitions

To check for the expected results you would need to evaluate some internal intermediate values rather than the output interface. It is not necessary that we should use multiple values from each partition. In the above scenario we can take -2 from invalid partition 1, 6 from valid partition P1, 7 from valid partition P2 and 15 from invalid partition 2.

Equivalence partitioning is not a stand alone method to determine test cases. It has to be supplemented by boundary value analysis. Having determined the partitions of possible inputs the method of boundary value analysis has to be applied to select the most effective test cases out of these partitions.

Limitations

In cases where the data ranges or sets involved approach simplicity (Example: 0-4, 5-8, 9-12), and testing all values would be practical, blanket test coverage using all values within and bordering the ranges should be considered. Blanket test coverage can reveal bugs that would not be caught using the equivalence partitioning method, if the software includes sub-partitions which are unknown to the tester.[citation needed] Also, in simplistic cases, the benefit of reducing the number of test values by using equivalence partitioning is diminished, in comparison to cases involving larger ranges (Example: 0-2000, 2001-3000, 3001-4000).

Further reading

- The Testing Standards Working Party website

- Parteg, a free test generation tool that is combining test path generation from UML state machines with equivalence class generation of input values.

- [1]

References

- ^ Burnstein, Ilene (2003), Practical Software Testing, Springer-Verlag, p. 623, ISBN 0-387-95131-8

![{\displaystyle [a,b]}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)