Totò: Difference between revisions

seen Help talk:IPA for Italian#Syntactic gemination you should have, young Ivan |

→External links: recat using AWB |

||

| Line 233: | Line 233: | ||

[[Category:Italian male composers]] |

[[Category:Italian male composers]] |

||

[[Category:Italian male writers]] |

[[Category:Italian male writers]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Musicians from Naples]] |

||

[[Category:Nastro d'Argento winners]] |

[[Category:Nastro d'Argento winners]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century composers]] |

[[Category:20th-century composers]] |

||

Revision as of 01:55, 11 January 2016

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

Totò | |

|---|---|

Totò | |

| Born | 15 February 1898 |

| Died | 15 April 1967 (aged 69) |

| Other names | Principe della risata |

| Occupation(s) | Comedian, actor, poet, writer, singer, songwriter |

| Years active | 1922–67 |

Prince Antonio Griffo Focas Flavio Angelo Ducas Comneno Porfirogenito Gagliardi De Curtis di Bisanzio, best known by his stage name Totò[1] (Italian pronunciation: [toˈtɔ]; 15 February 1898 – 15 April 1967) or as Antonio De Curtis, and nicknamed il Principe della risata ("the Prince of laughter"), was an Italian comedian, film and theatre actor, writer, singer and songwriter. He is widely considered one of the greatest Italian artists of the 20th century.[2] While he first gained his popularity as a comic actor, his dramatic roles, his poetry, and his songs are all deemed to be outstanding; his style and a number of his recurring jokes and gestures have become universally known memes in Italy. Writer and philosopher Umberto Eco has thus commented on the importance of Totò in Italian culture:

In this globalized universe where it seems that everybody's watching the same movies and eating the same food, there are still abysmal and overwhelming fractures separating one culture from another. How can two peoples [i.e. the Chinese and the Italian], one of which unknowing of Totò, truly understand each other?

Mario Monicelli, who directed some of the most appreciated of Totò's movies, thus described his artistic value:

With Totò, we got it all wrong. He was a genius, not just a grandiose actor. And we constrained him, reduced him, forced him into a common human being, and thus clipped his wings.

— Mario Monicelli, Cinquant'anni di cinema

As a comic actor, Totò is classified as an heir of the Commedia dell'Arte tradition, and has been compared to such figures as Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin.[4] He starred in about one hundred movies; while many of them were low profile, box-office driven productions, they tend to be all appreciated by the critics, at the very least, for Totò's performances many classify as masterpieces of Italian cinema. Prominent Italian directors and actors that have worked with Totò include Mario Monicelli, Alberto Lattuada, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Eduardo De Filippo, Peppino de Filippo, Aldo Fabrizi, Vittorio De Sica, Sophia Loren, Claudia Cardinale, Marcello Mastroianni, Nino Manfredi, Vittorio Gassman and Alberto Sordi.

Early life

Totò was born Antonio Clemente on 15 February 1898 in the Rione Sanità, a poor district of Naples, the illegitimate son of Anna Clemente from Sicily and Marquis Giuseppe De Curtis from Naples, who nevertheless did not legally recognize him until 1937. Totò much regretted growing up without a father, to the point that at the age of 35, when he was already very popular, he managed to have Marquis Francesco Maria Gagliardi Focas adopt him in exchange for a life annuity.[5] As a consequence, when Marquis de Curtis recognized him, Totò had become an heir of two noble families, hence claiming an impressive slew of titles. In 1946, when the Consulta Araldica—the body that advised the Kingdom of Italy on matters of nobility—ceased operations, the Tribunal of Naples recognized his numerous titles, so his complete name was changed from Antonio Clemente to Antonio Griffo Focas Flavio Ducas Komnenos Gagliardi de Curtis of Byzantium, His Imperial Highness, Palatine Count, Knight of the Holy Roman Empire, Exarch of Ravenna, Duke of Macedonia and Illyria, Prince of Constantinople, Cilicia, Thessaly, Pontus, Moldavia, Dardania, Peloponnesus, Count of Cyprus and Epirus, Count and Duke of Drivasto and Durazzo. For someone born and raised in one of the poorest Neapolitan neighbourhoods this must have been quite an achievement, but in claiming the titles (at the time they had become meaningless) the comedian also mocked them for their intrinsic worthlessness. In fact, when he was not using his stage name "Totò", he mostly referred to himself simply as "Antonio De Curtis".[5]

Totò's mother wanted him to become a priest, but as early as 1913, at the age of 15, he was already acting as a comedian in small theatres, under the pseudonym "Clerment". His early repertoire mostly consisted in imitations of Gustavo De Marco's characters.[5] In the minor venues where he performed, Totò had the chance to meet famous artists like Eduardo De Filippo, Peppino De Filippo and Carlo Scarpetta. He served in the army during World War I and then went back to acting. He learned the art of the guitti, the Neapolitan scriptless comedians, heirs to the tradition of the Commedia dell'Arte, and began developing the trademarks of his style, including a puppet-like, disjointed gesticulation, emphasized facial expressions, and an extreme, sometimes surrealistic, sense of humor, largely based on emphasizing primitive urges such as hunger and sexual desire.[6]

Career

In 1922, he moved to Rome to perform in bigger theatres. He performed in the genre of avanspettacolo, a vaudevillian mixture of music, ballet and comedy preceding the main act (hence its name, which roughly translates as "before show"). He became adept at these shows (also known as rivista – Revue), and in the 1930s he had his own company, with which he travelled across Italy.

In 1937, he appeared in his first movie Fermo con le mani, and later starred in other 96 films, many of which are still frequently broadcast on Italian television.

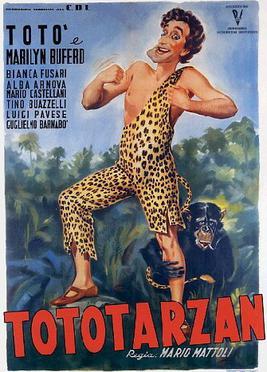

As the vast majority of his movies where essentially meant to showcase his performances, many have his name "Totò" in the title. Some of his best-known films are Fifa e Arena, Totò al Giro d'Italia, Totò Sceicco, Guardie e ladri, Totò e le donne, Totò Tarzan, Totò terzo uomo, Totò a colori (the first Italian color movie, 1952, in Ferraniacolor), I soliti ignoti, Totò, Peppino e la malafemmina, La legge è legge. In Pierpaolo Pasolini's The Hawks and the Sparrows and the episode Che cosa sono le nuvole from Capriccio all'italiana (released after his death), he displayed his dramatic skills. These roles gave him the artistic acknowledgment that had eluded him so far by more stringent critics, who only began to recognize his talent after his death.

In his vast cinematographic career, Totò had the opportunity to act side by side with virtually all major Italian actors of the time. With some of them he paired in several films, the most renowned and successful teams being established with Aldo Fabrizi and Peppino De Filippo. De Filippo was one of the few actors to have his name appear in movie titles along with that of Totò, for example in Totò, Peppino e la malafemmina and Totò e Peppino divisi a Berlino.

Totò's unmistakable figure, with his peculiarly irregular face (due to an accident in his teen years), and his unique trademark ability to disarticulate his body like a marionette, soon became very popular and his comic gags became part of the Italian culture. His typical character is uneducated, poor, vain, snobbish, selfish, naive, opportunist, hedonistic, lascivious and generally immoral, although fundamentally good-hearted. Partly because of the radical, naive immorality of his roles, some of his most spicy gags raised much controversy in a society that was both strictly Catholic and ruled by the conservative Democrazia Cristiana (Christian Democracy) party. For example, Totò's 1960 movie Che fine ha fatto Totò Baby? ("What ever happened to Totò Baby?", a parody of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?) included a cheeky and gross celebration of cannabis, in an era when drugs were perceived by the Italian audience as something as exotic as depraved and dangerous. Nevertheless, such controversies never affected the love of the Italian audience for him.

Writing

During the 1950s, he started to compose poetry. The best-known is probably 'A Livella, in which an arrogant rich man and a humble poor man meet after their deaths and discuss their differences. Totò was also a songwriter: Malafemmena (Wayward Woman), dedicated to his wife Diana after they separated, is considered a classic of Italian popular music.

Personal life

Totò had a reputation as a playboy. One of his lovers, the wellknown chanteuse and dancer Liliana Castagnola, committed suicide after their relationship ended. This tragedy marked his life. He buried Liliana in his family's chapel, and named his only daughter Liliana, born in 1933 to his first wife Diana Bandini Rogliani, whom he married in 1935. Another personal tragedy was the premature birth of his son Massenzio in 1954. The child died a few hours later. He was the son of Totò's mistress, Franca Faldini.

During a tour in 1956 he lost most of his eyesight due to an eye infection that he had ignored to avoid cancelling his show and disappointing his fans. The handicap however almost never affected his schedule and acting abilities.

Philanthropy

In the artistic milieu he was nicknamed "il Principe" (The Prince) and was famous for his generous spirit: having personally suffered poverty, he always tried to help and protect poorer colleagues as well as giving discreet, low-profile contributions to charity. Perhaps less known, but not less a credit to his generous soul, was his love for animals, especially dogs, testified by considerable donations and the funding of kennels throughout his life. The largest and most famous one, called "Ospizio degli Orfanelli" (The Orphans' Shelter), was founded 1960 and financed by him personally in Ostia, Rome.

Death

Totò died at the age of 69 on 15 April 1967 in Rome, after a series of heart attacks. Even in death he was unique—due to overwhelming popular request there were three funeral services: the first in Rome, a second in his birth city Naples—and a few days later, in a third one by the local Camorra boss, an empty casket was carried along the packed streets of the popular Rione Sanità quarter where he was born. Totò's birth home has been recently opened to the public as a museum, and his tombstone is frequently visited by fans, some of whom pray to him for help, as if he were a saint.

Filmography

Actor

Totò starred 97 films for the cinema. He has worked with 42 directors.

- Fermo con le mani

- Animali pazzi

- Saint John, the Beheaded (1940)

- L'allegro fantasma

- Due cuori fra le belve

- Il ratto delle Sabine

- I due orfanelli

- Fifa e arena

- Totò al giro d'Italia

- I pompieri di Viggiù

- Yvonne la nuit

- Totò cerca casa

- Totò Le Mokò

- L'imperatore di Capri

- Totò cerca moglie

- Napoli milionaria

- Figaro qua, Figaro là

- Le sei mogli di Barbablù

- Totò Tarzan

- Totò sceicco

- 47 morto che parla

- Totò terzo uomo

- Sette ore di guai

- Guardie e ladri

- Totò e i re di Roma

- Totò a colori

- Dov'è la libertà?

- Totò e le donne

- L'uomo, la bestia e la virtù

- Un turco napoletano

- Una di quelle

- Il più comico spettacolo del mondo

- Questa è la vita

- Miseria e nobiltà

- Tempi nostri

- I tre ladri

- Il medico dei pazzi

- Totò cerca pace

- L'oro di Napoli

- Totò all'inferno

- Totò e Carolina

- Siamo uomini o caporali?

- Racconti romani

- Destinazione Piovarolo

- Il coraggio

- La banda degli onesti

- Totò, lascia o raddoppia?

- Totò, Peppino e.. la malafemmina

- Totò, Peppino e i fuorilegge

- Totò, Vittorio e la dottoressa

- Totò e Marcellino

- Totò, Peppino e le fanatiche

- Gambe d'oro

- I soliti ignoti

- Totò a Parigi

- La legge è legge

- Totò nella luna

- Totò, Eva e il pennello proibito

- I tartassati

- I ladri

- Arrangiatevi!

- La cambiale

- Noi duri

- Signori si nasce

- Totò, Fabrizi e i giovani d'oggi

- Letto a tre piazze

- Risate di gioia

- Chi si ferma è perduto

- Sua Eccellenza si fermò a mangiare

- Totò, Peppino e...la dolce vita

- Totòtruffa 62

- I due marescialli

- Totò Diabolicus

- Totò contro Maciste

- Totò e Peppino divisi a Berlino

- Lo smemorato di Collegno

- Totò di notte n. 1

- I due colonnelli

- Il giorno più corto

- Totò contro i quattro

- Il monaco di Monza

- Le motorizzate

- Totò e Cleopatra

- Totò sexy

- Gli onorevoli

- Il comandante

- Totò contro il pirata nero

- Che fine ha fatto Totò Baby?

- Le belle famiglie

- Totò d'Arabia

- Gli amanti latini

- La mandragola

- Rita, la figlia americana

- Uccellacci e uccellini

- Operazione San Gennaro

- Le streghe

- Capriccio all'italiana

Screenwriter

TV

- TuttoTotò (1967)

Footnotes

- ^ Totò is a typical pet name for Antonio in Naples and its surroundings and it most properly comes from the Neapolitan dialect variant Totonno.

- ^ Cammarota, Il cinema di Totò, Fanucci Editore, 1985

- ^ Umberto Eco, Che capirà il cinese"L'espresso", 45 (LIII), 15 November 2007

- ^ Mario Monicelli

- ^ a b c Infanzia, antoniodecurtis.com.

- ^ Biography

Bibliography

- Giancarlo Governi. Il pianeta Totò. Gremese, 1992. ISBN 887605703X.

- Liliana De Curtis, Matilde Amorosi. Totò a prescindere. Mondadori, 1992. ISBN 8804584521.

- Ennio Bìspuri. Totò: principe clown. Guida Editori, 1997. ISBN 8871881575.

- Alberto Anile. Il cinema di Totò: (1930-1945) : l'estro funambolo e l'ameno spettro. Le mani, 1997. ISBN 8880120514.

- Associazione Antonio De Curtis. Totò, partenopeo e parte napoletano: il teatro, la poesia, la musica. Marsilio, 1998. ISBN 8831770861.

- Alberto Anile. I film di Totò (1946-1967): la maschera tradita. Le mani, 1998.

- Costanzo Ioni, Ruggero Guarini. Tutto Totò. Gremese Editore, 1999. ISBN 8877423277.

- Ennio Bìspuri. Vita di Totò. Gremese Editore, 2000. ISBN 8884400023.

- Franca Faldini, Goffredo Fofi. Totò: l'uomo e la maschera. L'Ancora del Mediterraneo, 2000. ISBN 8883250133.

- Paolo Pistolese. Totò, stars and stripes. Cinecittà, 2000.

- Orio Caldiron. Totò. Gremese Editore, 2001. ISBN 8877424133.

- Antonio Napolitano. Totò, uno e centomila. Tempo Lungo Ed., 2001. ISBN 8887480141.

- Fabio Rossi. La lingua in gioco: da Totò a lezione di retorica. Bulzoni, 2002. ISBN 888319697X.

- Orio Caldiron. Il principe Totò. Gremese Editore, 2002. ISBN 8884402166.

- Liliana De Curtis. Totò, mio padre. Rizzoli, 2002. ISBN 8817117579.

- Daniela Aronica, Gino Frezza, Raffaele Pinto. Totò. Linguaggi e maschere del comico. Carocci, 2003. ISBN 8843027867.

- Patricia Bianchi, Nicola De Blasi. Totò parole di attore e di poeta. Dante & Descartes, 2007. ISBN 8861570127.

- Sonia Pedalino. Totò e la maschera. Firenze Atheneum, 2007. ISBN 8872553040.

- Edmondo Capecelatro, Daniele Gallo. Totò: vita e arte di un genio. Viator, 2008. ISBN 8890387203.

- Liliana De Curtis, Matilde Amorosi. Malafemmena: il romanzo dell'unico, vero, grande amore di Totò. Mondadori, 2009. ISBN 8804584521.

- Ornella Di Russo. Cogito ergo De Curtis. Fermenti, 2013. ISBN 8897171389.