Theodore Psalter: Difference between revisions

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

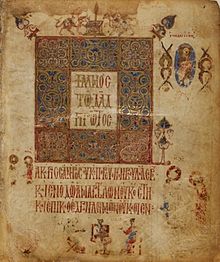

[[File:Theodore Psalter 2.png|alt=Courtesy of the British Library; London, U.K.|thumb|Theodore Psalter |

[[File:Theodore Psalter 2.png|alt=Courtesy of the British Library; London, U.K.|thumb|Theodore Psalter |

||

MS 19352, ff 191v-192 |

MS 19352, ff 191v-192 |

||

]] |

|||

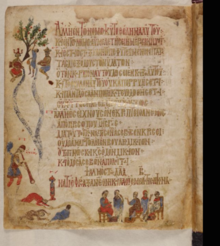

[[File:Theodore Psalter page 189v, Ps. 151.jpg|alt=Courtesy of the British Library; London, U.K.|thumb|Theodore Psalter |

|||

MS 19352, ff 189v-191 |

|||

]] |

]] |

||

Theodore was a ''protopresbteros,'' or an archpriest - a kind of clerk at the Stoudious Monastery, a monastery known for its rigorous academic and artistic excellence. The name of the monastery seems to be erased in the colophon, or the place where publishing information occurs in the Psalter. Theodore wrote that he created the book because “Michael” ordered it. Michael was the abbot at the Stoudious Monastery.[3] It is worth noting that Theodore was not the same person as ''Theodore of Stoudious'', however. That man had lived two centuries before, and was also a monk at the same monastery who was persecuted for his devotion to religious icons or images during the Iconoclastic period. Theodore of Stoudious eventually died from the effects of persecution, and was later made a saint by the church. |

Theodore was a ''protopresbteros,'' or an archpriest - a kind of clerk at the Stoudious Monastery, a monastery known for its rigorous academic and artistic excellence. The name of the monastery seems to be erased in the colophon, or the place where publishing information occurs in the Psalter. Theodore wrote that he created the book because “Michael” ordered it. Michael was the abbot at the Stoudious Monastery.[3] It is worth noting that Theodore was not the same person as ''Theodore of Stoudious'', however. That man had lived two centuries before, and was also a monk at the same monastery who was persecuted for his devotion to religious icons or images during the Iconoclastic period. Theodore of Stoudious eventually died from the effects of persecution, and was later made a saint by the church. |

||

Revision as of 05:18, 7 March 2016

Theodore Psalter

The Theodore Psalter is an illustrated manuscript and compilation of the Psalms and the Odes from the Old Testament written by the scribe named Theodore from the Stoudios Monastery, a native of Cappadocian Caesarea. He completed the psalter in 1066. The Psalms are written in metered verse, and are thought to be musical. They were compared to a harp, or an instrument of music.** Many psalters have been curated, but the Byzantine psalters have a special place in history because of their artistic qualities during the golden age of the Byzantine Empire, as well as for images and icons painted by hand, and for the style of script used. The art within the Byzantine psalters were specifically unique because of the use of images or icons in the shadow of controversy surrounding them during the earlier Iconoclastic Debate, also known as Iconoclasm. This period witnessed much debate and hostility surrounding the use of icons and images.

The Byzantine Psalter

A psalter is a book made specifically to contain the 150 psalms from the book of Psalms from the Old Testament. Psalters included the odes or canticles, which are songs or prayers in song form from the Old Testament, and are gathered together at the end of Psalms. Psalters were created purely for liturgical purposes, and illustration was an important part of Byzantine psalters. [1] There were two kinds of psalter illustration: marginal and aristocratic. A marginal psalter had illustrations in the margins of the book, and the aristocratic were more lavish. The aristocratic illustrations did not appear in the margins; sometimes an entire page was devoted to a single illustration.

The Psalms were the most popular books of the Old Testament to Byzantine. “Like a garden, the book of Psalms contains, and puts in musical form, everything that is to be found in other books, and shows, in addition, its own particular qualities.”[2] Additionally, the psalters could be a form of guided prayer for the reader; as they read they were also praying to God, or Christ was thought to be speaking to the reader as they read.

Theodore the Scribe

Theodore was a protopresbteros, or an archpriest - a kind of clerk at the Stoudious Monastery, a monastery known for its rigorous academic and artistic excellence. The name of the monastery seems to be erased in the colophon, or the place where publishing information occurs in the Psalter. Theodore wrote that he created the book because “Michael” ordered it. Michael was the abbot at the Stoudious Monastery.[3] It is worth noting that Theodore was not the same person as Theodore of Stoudious, however. That man had lived two centuries before, and was also a monk at the same monastery who was persecuted for his devotion to religious icons or images during the Iconoclastic period. Theodore of Stoudious eventually died from the effects of persecution, and was later made a saint by the church.

Rise of Liturgy and Liturgical Books

The Byzantine Empire witnessed a very prolific movement in the creation of art. The legalization of Christianity by Constantine in 313 inspired works of art linked to this religious movement, and the art became a new rising star. Church services created and inspired by devotion to Christianity were called ‘liturgical services. ’ [4] Liturgy was also the concept behind icons, pilgrimages, sainthood, ceremonies, rituals, and the creation of books. The act of reading the Psalms was not new. It was thought that icons created a mental universe (for the reader) imbued with images derived from texts. [5] The manuscripts were created to transport the reader to a different place, a place with high spiritual aspirations. It was thought that the Psalms allowed the reader to take a ‘journey with an angelic mind’. Jews based this on more traditional thoughts about the Psalms. Augustine wrote about these phenomena, specifically about Psalms 41:

“One reason holy books were created was to construct within the reader ‘with an angelic mind’, the Tabernacle, its furniture and its rites, as described in Exodus 25ff. This ancient Jewish meditational exercise permeates early Christianity as well, nowhere better expressed than in Augustine’s meditation (ennarration) on Psalm 41, Quemadmodum desiderat cervus, which became a touchstone for the life of prayer in the desert. In this psalm (in the version known to Augustine), the psalmist describes his ascent to the house of God, beginning in God’s tent, tabernaculum, on earth.”[6] This is another explanation, “While the psalmist walks about the tabernacle her hears from within it the melody-voice or instrument – that he follows: it is the sweetness that draws him through and up to the celestial dwelling itself. Augustine focuses on the agency of this movement, the road he took and the manner – ductus – in which he was led.”[7]

Additionally, the sense of sight, or the act of seeing, according to Art History professor Hebert L. KJessler was the most important sense or activity in the Middle Ages. “In medieval theory, however, sight was the most powerful sense and, following classical rhetorical formulations, visual images were considered more effective even than words in moving the soul. By engaging the passions and evoking fascination and fear, pictures were considered particularly powerful in rendering the words of Scripture memorable.[8]

Illustrations in the Theodore Psalter

The Theodore Psalter has 440 miniatures, or illustrations. They are ‘marginal’ miniatures; they also appear in the margins of the book. The colors of the miniatures range from red to blue and gold, and also include green, grey and white. These included illustrations from the Gospels, liturgical illustrations and hagiographical miniatures, or stories about Christ.[9] The word miniature means illustration, and originates with the word minium, which had nothing to do with size or the word ‘minimum’. Instead the word refers to the red lead of the pencils used in the 9th Century for these psalters. Throughout the psalter there are both red and blue lines connecting the miniatures to text, much like the way we today link text to photos or other websites. The Theodore Psalter miniatures convey allegorical meaning from the Psalms or the Odes, and have “an extra layer of meaning supplied by images displaying vigorous anti-Iconoclastic propaganda.”[10]

Style of Images

The Theodore Psalter is considered to be richer in illustrations and images than previous psalters, and there is scholarly consensus that Theodore was unusually creative with the use of icons.[11]. The illustrations are examples of the experiential art that Byzantine and medieval art is known for. There are animals and men playing music, bird and vegetation. Art historian and professor Bissera Pentcheva points out that the icon must be experienced with the senses in her book The Sensual Icon.

“Focusing on the Byzantine icon, this study plunges into the realm of senses and performative objects. To us, the Greek word for icon, designates portraits of Christ, Mary, angels, saints, and prophets painted in encaustic or tempera on wooden boards. By contrast, eikon in Byzantium had a wide semantic spectrum ranging from hallowed bodies permeated by the Spirit, such as the Stylite saintes or the Eucharist, to imprinted images on the surfaces of metal, stone, and earth. Eikon designated matter imbued with divine pneuma, releasing charis, or grace. As matter, this object was meant to be physically experienced. Touch, smell, taste, and sound were part of “seeing” an eikon.”[12]

Text - Carolingian Miniscule

The script used in the Theodore Psalter is called Carolingian Miniscule. It is a kind of calligraphy established in the 8th and 9th Century by Charlemagne. It is the foundational script that forms the basis of the present day Roman upper and lower case type.[13] The letters appear in red and gold, and the cover has those colors alongside blue.

Art and Text in the Theodore Psalter

The relationship of icons and text, especially religious text, is an ongoing topic of interest to scholars:

“Art and text, the interface between images and words, is one of the oldest issues in art history. Are works of art and writings different but parallel forms of expression? Are they intertwined and interdependent? Can art ever stand alone and apart from text or is it always enmeshed in the meanings expressed in the written and the oral that make it perpetually exposed to subjective interpretation?Byzantium was a culture in which the interactions between word and image underpinned, in many ways, the whole meaning of art. For the Byzantines, as a People of the Book, the interface between images and words, and, above all, Christ, the Word of God, was crucial. The dynamic between art and text in Byzantium is essential for understanding Byzantine society, where the correct relationship between the two was critical to the well being of the state.”[14]

Theodore Psalter Today

Today the Theodore Psalter hangs in the British Library in London. The British Library is the largest library in the world. A great deal of work has gone into preserving this psalter, now almost a thousand years old, and anyone can view it and experience it. If you can’t make it to Great Britain, you can still see and experience this beautiful psalter, as it has been digitized. In fact, the reader may see its pages turn. The link to the British Museum’s website for the Theodore Psalter is http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_19352

Bibliography

British Museum, britishmuseum.org; Great Russell St, London WC1B 3DG, United Kingdom

Carruthers, Mary; Rhetoric beyond words; delight and persuasion in the arts of the Middle Ages; Cambridge University Press, New York, 2010.

James, Liz; Art and Text in Byzantine Culture; Hong Kong by Golden Cup; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.UK. 2007, page 1.

Kazhdan, A. P., Alice-Mary Maffry Talbot, Anthony Cutler, Timothy E. Gregory, and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print.

Kessler, Herbert L; Seeing Medieval Art; University of Toronto Press; Toronto, Canada, 2011.

Pentcheva, Bissera V.; The Sensual Icon: space, ritual, and the senses in Byzantium; The Pennsylvania State University; Hong Kong; 2010; page 1.

Studies on the liturgies of the Christian East: selected papers of the Third International Congress of the Society of Oriental Liturgy, Volos, and May 26-30, 2010. Page 228.

References

[1] Kazhdan, A. P., Alice-Mary Maffry Talbot, Anthony Cutler, Timothy E. Gregory, and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print. Page 1752.

[2] Kazhdan, A. P., Alice-Mary Maffry Talbot, Anthony Cutler, Timothy E. Gregory, and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print. Page 1752.

[3], Kazhdan, A. P., Alice-Mary Maffry Talbot, Anthony Cutler, Timothy E. Gregory, and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print. Page 2046.

[4] Kazhdan, A. P., Alice-Mary Maffry Talbot, Anthony Cutler, Timothy E. Gregory, and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print. Page 1240.

[5] Studies on the liturgies of the Christian East: selected papers of the Third International Congress of the Society of Oriental Liturgy, Volos, May 26-30, 2010. Page 228.

[6] Rhetoric beyond words: delight and persuasion in the arts of the Middle Ages, edited by Mary Carruthers; Cambridge University Press, New York, 2019. Page 194-95.

[7] Rhetoric beyond words: delight and persuasion in the arts of the Middle Ages, edited by Mary Carruthers; Cambridge University Press, New York, 2019. Page 195.

[8] Kessler, Herbert L. ; Seeing Medieval Art; University of Toronto Press, Higher Education Division, 2011. Page 176-77.

[9] Kazhdan, A. P., Alice-Mary Maffry Talbot, Anthony Cutler, Timothy E. Gregory, and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print. Page 2046.

[10] Kazhdan, A. P., Alice-Mary Maffry Talbot, Anthony Cutler, Timothy E. Gregory, and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print. Page 1753.

[11] Kazhdan, A. P., Alice-Mary Maffry Talbot, Anthony Cutler, Timothy E. Gregory, and Nancy Patterson Ševčenko. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print. Page 2046.

[12] Pentcheva, Bissera V.: The Sensual Icon: space, ritual, and the senses in Byzantium; The Pennsylvania State University; Hong Kong; 2019; page 1.

[13] Encyclopedia Britannica: http://www.britannica.com/art/Carolingian-minuscule

[14] James, Liz; Art and Text in Byzantine Culture; Hong Kong by Golden Cup; Cambridge University Press, 2007, page 1.

This article, Theodore Psalter, has recently been created via the Articles for creation process. Please check to see if the reviewer has accidentally left this template after accepting the draft and take appropriate action as necessary.

Reviewer tools: Inform author |