2016 Atlantic hurricane season: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit |

MarioProtIV (talk | contribs) m Reverted 1 edit by 64.237.239.117 (talk) to last revision by Trainbuzz. (TW) |

||

| Line 177: | Line 177: | ||

==Seasonal summary== |

==Seasonal summary== |

||

{{main article|Timeline of the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season}} |

{{main article|Timeline of the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season}} |

||

{{main article|Hurricane Matthew}} |

|||

<center> |

<center> |

||

<timeline> |

<timeline> |

||

| Line 199: | Line 198: | ||

id:C3 value:rgb(1,0.76,0.25) legend:Category_3_=_111–129_mph_(178–208_km/h) |

id:C3 value:rgb(1,0.76,0.25) legend:Category_3_=_111–129_mph_(178–208_km/h) |

||

id:C4 value:rgb(1,0.56,0.13) legend:Category_4_=_130–156_mph_(209–251_km/h) |

id:C4 value:rgb(1,0.56,0.13) legend:Category_4_=_130–156_mph_(209–251_km/h) |

||

id:C5 value:rgb(1,0.38,0.38) |

id:C5 value:rgb(1,0.38,0.38) legend:Category_5_=_≥157_mph_(≥252_km/h) |

||

Backgroundcolors = canvas:canvas |

Backgroundcolors = canvas:canvas |

||

| Line 227: | Line 226: | ||

from:14/09/2016 till:25/09/2016 color:TS text:"Karl (TS)" |

from:14/09/2016 till:25/09/2016 color:TS text:"Karl (TS)" |

||

from:19/09/2016 till:25/09/2016 color:TS text:"Lisa (TS)" |

from:19/09/2016 till:25/09/2016 color:TS text:"Lisa (TS)" |

||

from:28/09/2016 till:09/10/2016 color:C5 text:"[[Hurricane Matthew|Matthew |

from:28/09/2016 till:09/10/2016 color:C5 text:"[[Hurricane Matthew|Matthew(C5)]]" |

||

from:04/10/2016 till:09/10/2016 color:C2 text:"Nicole (C2)" |

from:04/10/2016 till:09/10/2016 color:C2 text:"Nicole (C2)" |

||

bar:Month width:5 align:center fontsize:S shift:(0,-20) anchor:middle color:canvas |

bar:Month width:5 align:center fontsize:S shift:(0,-20) anchor:middle color:canvas |

||

Revision as of 12:28, 9 October 2016

| 2016 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | January 12, 2016 |

| Last system dissipated | Season ongoing |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Matthew |

| • Maximum winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| • Lowest pressure | 934 mbar (hPa; 27.58 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 15 |

| Total storms | 14 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 979 total |

| Total damage | > $7.751 billion (2016 USD) |

| Related article | |

The 2016 Atlantic hurricane season is the most active Atlantic hurricane season and costliest since 2012 and the deadliest since 2008. It officially started on June 1 and will end on November 30.[1] The season began nearly five months before the official start, with Hurricane Alex forming in the Northeastern Atlantic in mid-January, the first Atlantic January hurricane since Hurricane Alice in 1955.

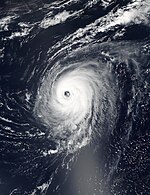

The strongest, costliest and deadliest storm of the season was Hurricane Matthew, the southernmost Category 5 Atlantic hurricane on record, and the first Category 5 hurricane to form in the Atlantic since Felix in 2007. With at least 897 deaths attributed to it, Hurricane Matthew is the deadliest Atlantic hurricane since Stan in 2005.

Most forecasting groups have expected this season to be an above average season, due to a combination of factors including an expected transition to La Niña and warmer than normal sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean, and Western Atlantic, despite near-average sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Main Development Region near Cape Verde. So far, eleven of the fifteen developed tropical cyclones (except Fiona, Ian, Lisa and Nicole) have impacted land, and seven of those storms caused loss of life, directly or indirectly. At least 981 people have died as of October 8, making this season the deadliest since 2008.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | |

| Average (1981–2010[2]) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | ||

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 7 | ||

| Record low activity | 4 | 2† | 0† | ||

| TSR[3] | December 16, 2015 | 13 | 5 | 2 | |

| TSR[4] | April 5, 2016 | 12 | 6 | 2 | |

| CSU[5] | April 14, 2016 | 13 | 6 | 2 | |

| CCU[6] | April 15, 2016 | 13 | 7 | 4 | |

| NCSU[7] | April 15, 2016 | 15–18 | 8–11 | 3–5 | |

| UKMO[8] | May 12, 2016 | 14* | 8* | N/A | |

| NOAA[9] | May 27, 2016 | 10–16 | 4–8 | 1–4 | |

| TSR[10] | May 27, 2016 | 17 | 9 | 4 | |

| CSU[11] | June 1, 2016 | 14 | 6 | 2 | |

| WT[12] | June 1, 2016 | 14 | 9 | 3 | |

| CSU[13] | July 1, 2016 | 15 | 6 | 2 | |

| TSR[14] | July 5, 2016 | 16 | 8 | 3 | |

| CSU[15] | August 4, 2016 | 15 | 6 | 2 | |

| TSR[15] | August 5, 2016 | 15 | 7 | 3 | |

| WT[16] | August 8, 2016 | 14 | 7 | 2 | |

| NOAA[17] | August 11, 2016 | 12–17 | 5–8 | 2–4 | |

| WT[18] | September 6, 2016 | 14 | 8 | 2 | |

| Actual activity |

14 | 6 | 2 | ||

| * June–November only. † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

Ahead of and during the season, several national meteorological services and scientific agencies forecast how many named storms, hurricanes and major hurricanes will form during a season and/or how many tropical cyclones will affect a particular country. These agencies include the Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) Consortium of the University College London, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Colorado State University (CSU). The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year.[3] Some of these forecasts also take into consideration what happened in previous seasons and the predicted weakening of the 2014–16 El Niño event.[3] On average, an Atlantic hurricane season between 1981 and 2010 contained twelve tropical storms, six hurricanes, and two major hurricanes, with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of between 66 and 103 units.[2]

The first forecast for the year was issued by CSU on December 10, who anticipated that one of four different scenarios could occur.[19] TSR subsequently issued their first outlook for the 2016 season during December 16, 2015 and predicted that activity would be about 20% below the 1950–2015 average, or about 15% below the 2005–2015 average.[3] Specifically they thought that there would be 13 tropical storms, 5 hurricanes, 2 major hurricanes and an ACE index of 79 units.[3] A few months later, TSR issued their second prediction for the season during April 6, 2016 and lowered the predicted number of named storms to 12 but raised the number of hurricanes to 6.[4] On April 14, CSU predicted that the season would be near-normal, predicting 13 named storms, 6 hurricanes and 2 major hurricanes with ACE near 93.[5] On April 15, North Carolina State University predicted the season would be very active, with 15-18 named storms, 8-11 hurricanes and 3-5 major hurricanes. A month later, the United Kingdom Met Office (UKMO) released its forecast, predicting a slightly above-average season with 14 named storms and 8 hurricanes. It also predicted an ACE index of 125, above the defined average ACE index at 103.[8] On May 27, NOAA issued its first outlook calling for a near-normal season with a 70% chance that 10-16 named storms could form, including 4-8 hurricanes of which 1-4 could reach major hurricane status. NOAA also stated that there is a 45% chance of a near-normal season, 30% chance of an above-normal season and 25% chance of a below-normal season. Also on May 27, TSR substantially increased their forecast numbers, predicting activity would be about 30% above the average with 17 named storms, 9 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes and an ACE near 130. The reason for the increased activity forecast was the increased likelihood of La Niña forming during the season in addition to a trend towards a negative North Atlantic Oscillation, which generally favors a warmer tropical Atlantic. TSR predicted that there is a 57% chance that the 2016 Atlantic season would be above-normal, a 33% chance it would be near-normal, and only a 10% chance it would be below-normal.

CSU updated their forecast on June 1 to include 14 named storms, 6 hurricanes and 2 major hurricanes to include recently formed Tropical Storm Bonnie. It was again updated on July 1 to include 15 named storms, 6 hurricanes and 2 major hurricanes, to accommodate for tropical storms Colin and Danielle. On July 5, TSR released their fourth forecast for the season, slightly lowering the predicted numbers to 16 tropical storms, 8 hurricanes and 3 major hurricanes.[14] On August 5, TSR released their final forecast for the season, lowering the numbers to 15 named storms and 7 hurricanes due to the influence that La Niña being less than anticipated previously.[15]

Seasonal summary

Unable to compile EasyTimeline input:

Timeline generation failed: 3 errors found

Line 8: ScaleMinor = grid:black unit:month increment: start:01/01/2016

- ScaleMinor definition incomplete. No value specified for attribute 'increment'.

Line 44: bar:Month width:5 align:center fontsize:S shift:(0,-20) anchor:middle color:canvas

- Invalid statement. No '=' found.

Line 45: from:01/01/2016 till:01/02/2016 text:January

- New command expected instead of data line (= line starting with spaces). Data line(s) ignored.

On January 12, an extratropical cyclone over the eastern Atlantic Ocean developed into a subtropical storm. Assigned the name Alex, the system soon developed into a fully tropical hurricane—the first such storm in January since Alice in 1955. Alex then made landfall over Terceira Island, Azores, as a strong tropical storm, before becoming extratropical on January 15. The next tropical cyclone developed in late May, originating as a tropical depression on May 27. The next day, the depression developed into Tropical Storm Bonnie, the first occurrence of two pre-season Atlantic storms since 2012 and the third occurrence since 1951. Bonnie made landfall south of Charleston at Tropical depression strength, but regenerated on June 2.[citation needed]As Bonnie dissipated on June 5, Tropical Storm Colin formed, becoming the earliest occurrence of a season's third named storm since reliable records began, surpassing the previous record set in 1887.[20][21] On June 20, Danielle became the earliest fourth named storm, surpassing the previous record set by Tropical Storm Debby in 2012 by 3 days.[22] However no storms formed in July, an occurrence not seen since 2012.[23] Activity revamped significantly in August. Earl became the deadliest hurricane in Mexico since Hurricane Stan in 2005.[24] Gaston became the first major hurricane of the season on August 28, while Tropical Depression Eight threatened the Outer Banks of North Carolina. On September 2, Hermine became the first hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico since Hurricane Ingrid and broke the eleven year record since Hurricane Wilma that a hurricane struck Florida.[citation needed]Hurricane Matthew became the first Category 5 Atlantic hurricane since Hurricane Felix of 2007, and simultaniously became the southernmost storm of that intensity, beating the record set by Hurricane Ivan.[25] Later, the storm became the first storm since Hurricane Cleo to make landfall in Haiti as a Category 4 hurricane, having weakened slightly from its earlier peak.[26] Matthew wrought 896 deaths during its long passage; the storm also threatened to become the first major hurricane to strike Florida since Wilma, though its eye remained several miles offshore. However, early on October 8, the eye of Matthew made landfall in South Carolina with a barometric pressure of 967 mbar, becoming the strongest hurricane to landfall in the United States since Hurricane Ike, and the first hurricane to make landfall in South Carolina since Hurricane Gaston in 2004. In addition, Matthew was the first hurricane to make landfall north of Georgia in October since Hurricane Hazel.

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season, as of 03:00 UTC on October 9, is 105.84 units.[nb 1] This is above the 1951-2000 full-season average of 93 units.

Storms

Hurricane Alex

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | January 12 – January 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 981 mbar (hPa) |

A weak area of low pressure developed over northwestern Cuba in association with a stationary front on January 6. The frontal wave intensified as it moved into the central Atlantic, temporarily attaining hurricane-force winds by January 10. Steered by anomalous high pressure, the disturbance turned southeast and tracked over warmer waters. Its associated fronts dissipated, its wind field became more symmetric, and convection increased near the center, leading to the formation of Subtropical Storm Alex by 18:00 UTC on January 12. Despite marginal ocean temperatures, Alex benefited from rapidly cooling upper-air temperatures, and it intensified quickly while turning northeast. The presence of deeper convection and an eye on conventional satellite showcased the storm's transition into a fully tropical cyclone and intensification into a hurricane by 06:00 UTC on January 14. Six hours later, it peaked with maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). Alex turned north after peak, and the storm weakened to a tropical storm before making landfall on Terceira Island, Azores. With decreasing core convection and an impinging warm front, Alex transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by 18:00 UTC on January 15 and was absorbed by a larger extratropical low two days later.[27]

The precursor disturbance to Hurricane Alex produced gusts up to 60 mph (97 km/h) on Bermuda, as well as swells up to 20 ft (6 km) offshore; this disrupted air travel, downed trees, caused sporadic power outages, and suspended ferry services.[28] In the Azores, the cyclone produced maximum rainfall accumulations up to 4.04 in (103 km) in Lagoa.[29] Peak gusts of 57 mph (92 km/h) affected Ponta Delgada, causing minor to moderate damage.[30] Landslides also contributed to minor damage.[31] One death occurred when a victim that suffered a heart attack was unable to take off due to unsettled conditions.[32]

Tropical Storm Bonnie

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 27 – June 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

On May 24, the NHC began monitoring an area of disturbed weather resultant from the interaction of a weakening cold front and an upper-level trough.[33] A surface area of low pressure formed late the next day,[34] eventually gaining sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC on May 27.[35] Steered west-northwest within an only marginally conducive environment, the depression slowly intensified into Tropical Storm Bonnie a day later.[36] The continued effects of high wind shear and dry air caused the cyclone's appearance to degenerate early on May 29,[37] and Bonnie weakened back to tropical depression strength less than an hour prior to its landfall just east of Charleston, South Carolina.[38][39] The depression meandered over South Carolina for over a day before regressing to a remnant low over the northeastern portion of the state at 15:00 UTC on May 30.[40] However, Bonnie regenerated into a tropical depression on June 2 amidst more favorable conditions.[41] Late the next day, Bonnie re-strengthened back to a tropical storm due to a burst of convection.[42] Bonnie then weakened to a tropical depression on June 4 and then early on June 5, Bonnie finally dissipated into a remnant low.[43]

Upon formation, a tropical storm warning was hoisted in South Carolina from the Savannah River to the Little River Inlet.[35] Heavy rains associated with Bonnie led to localized flooding, prompting the South Carolina Highway Patrol to close the southbound lanes of Interstate 95 in Jasper County, South Carolina.[44] Rip currents along the coastline of the Southeast United States led to dozens of water rescues; the body of one 20-year-old man was recovered in Brevard County, Florida, after he drowned,[45] while the body of a 21-year-old man was recovered in New Hanover County, North Carolina, several days after he went missing.[46] In all, Bonnie is estimated to have caused more than $640,000 (2016 USD) in structural damage.[47]

Tropical Storm Colin

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 5 – June 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

In early June, a low pressure system entered the Caribbean Sea. The low remained disorganized with only isolated convection, mostly in the eastern quadrant. Convection began to wrap into the center as the storm curved northward into the Gulf of Mexico on June 3.[48] After the low passed over the Yucatán Peninsula on June 5, the National Hurricane Center upgraded it to Tropical Depression Three and tropical storm warnings were issued for the Big Bend region of Florida.[49][50] Later that day, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Colin, just after tropical storm watches were put in place for eastern Florida and Georgia.[51][52] The formation into a tropical storm marked the earliest formation on record of the third named storm within the Atlantic basin, exceeding the previous record set in 1887 by seven days.[20][21] Gradually curving northeastwards, Colin remained disorganized as it accelerated towards the coast of Florida on June 6; in their forecast discussion, the NHC noted that their uncertainty in locating the circulation center, instead taking the midpoint between two small-scale circulations. However, a strong burst of convection increased the winds to 50 mph (85 km/h).[53] Maintaining its intensity, Colin continued accelerating to the northeast and made landfall in the Big Bend region just after 03:00 UTC on June 7.[54] Failing to weaken over land, Colin began undergoing extratropical transition after the increasingly ill-defined circulation moved off the coast of Georgia,[55] and became fully extratropical hours later.[56] It remained extratropical and intact for nearly a week before merging with another extratropical cyclone on June 14.[citation needed]

Much of Florida experienced heavy rainfall, and flash flood and tornado warnings were issued. At least three people drowned along the Florida Panhandle due to rip currents, and a fourth remains missing but is presumed dead.[57][58][59] Damage from Colin in the Tampa Bay area totaled $10,000 (2016 USD).[60]

Tropical Storm Danielle

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 19 – June 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on June 8, reaching the southwestern Caribbean Sea by June 15. Convection increased that day, and further organized after the system entered the Bay of Campeche three days later, subsequently leading to the formation of a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on June 19. Steered west-northwest and then northwest by a mid-level ridge, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Danielle by 06:00 UTC on June 20 and attained peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) six hours later. Interaction with land began to weaken the storm a few hours later, and Danielle made landfall near Tamiahua, Mexico with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). The storm rapidly weakened as it moved inland, falling to tropical depression intensity by 00:00 UTC on June 21 and degenerating into a remnant low six hours later. The remnant low continued inland before dissipating over the mountains of eastern Mexico that same day.[61]

Across much of Veracruz, officials suspended school activities and the Port of Veracruz was temporarily closed. Flooding in the Pueblo Viejo Municipality affected 1,200 families and prompted activation of public shelters.[62] In Ciudad Madero, Tamaulipas, a homeless man drowned in a storm drain during a flash flood.[63]

Hurricane Earl

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 2 – August 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 979 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began monitoring a tropical wave in the central Atlantic on July 28.[64] The disturbance's rapid movement prevented development for several days until it passed Jamaica on August 2, when a reconnaissance aircraft confirmed the presence of a closed circulation; already possessing tropical storm-force winds, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Earl.[65][66] Steered generally westward by a ridge over the South United States, Earl intensified amid warm ocean temperatures and low shear, attaining hurricane intensity and peaking with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) on August 3.[67][68] Earl made landfall just southwest of Belize City, Belize around 06:00 UTC on August 4.[69] It quickly weakened over land, although it emerged over the southern Bay of Campeche the following day while still maintaining minimal tropical storm intensity.[70] A Hurricane Hunters mission flew into Earl later on August 5, unexpectedly measuring 60 mph (95 km/h) winds.[71] The cyclone maintained these winds up to landfall just south of Veracruz, Veracruz around 02:00 on August 6.[72] Once inland, Earl quickly weakened and the storm's circulation dissipated by 15:00 UTC.[73]

The precursor to Earl brought heavy rain and gusty winds to the Lesser Antilles and Greater Antilles. Strong winds in the Dominican Republic downed a power line onto a bus, subsequently causing a fire that killed six people. A boat crash in Samaná Bay killed seven people.[74][75] Significant impacts were reported in Belize after Earl moved ashore as a hurricane, including downed trees and power lines, blown transformers, damaged or ripped-off roofs, coastal and inland flooding, and a significant storm surge.[76] Landslides in Mexico following the storm's second landfall resulted in an additional 54 deaths.[77]

Tropical Storm Fiona

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 17 – August 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

Late on August 14, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave and its associated convection off the western coast of Africa for potential development.[78] Steered northwest toward a weakness in the subtropical ridge over the central Atlantic, the wave organized sufficiently to be declared a tropical depression by 03:00 UTC on August 17.[79] The depression slowly organized after formation, and the development of a central dense overcast feature prompted an upgrade to Tropical Storm Fiona by 21:00 UTC on August 17.[80] Despite strong westerly shear, abundant mid-level dry air, and an otherwise disheveled satellite appearance, an ASCAT pass showcased Fiona's peak intensity with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) around 03:00 UTC on August 20.[81] Although sporadic bursts of convection continued amid the hostile environment, Fiona weakened to a tropical depression by 03:00 UTC on August 22 and degenerated into a remnant low early on August 23.[82][83]

Hurricane Gaston

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 22 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 956 mbar (hPa) |

On August 17, the NHC highlighted the potential for tropical cyclone development off the western coast of Africa in subsequent days.[84] A weak area of low pressure associated with a tropical wave emerged into the eastern Atlantic three days, later,[85] and the disturbance steadily coalesced into a tropical depression by 21:00 UTC on August 22.[86] The newly-formed depression organized while headed northwest, intensifying into Tropical Storm Gaston six hours after classification and attaining hurricane intensity by 09:00 UTC on August 25 in accordance with data from the NASA Global Hawk unmanned aircraft.[87][88] After its initial peak in intensity, Gaston's satellite appearance began to degrade as an upper-level low imparted strong southwesterly shear on the cyclone.[89] Upper-level winds slackened early on August 27, and a timely microwave pass highlighted the presence of a low-level eye well embedded in the storm's central dense overcast, indicating the resumption of Gaston's intensification phase.[90]

Although the cyclone continued its northwest heading, its motion slowed in a weak steering regime. Amid low shear and warm ocean temperatures, Gaston attained hurricane intensity for a second time by 03:00 UTC on August 28 and further intensified to become a Category 3 hurricane, the first major hurricane of the season, by 21:00 UTC that same day.[91][92] With a symmetric ring of deep convection surrounding a distinct eye, Gaston ultimately peaked with sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) six hours later. A mid-level trough moving southeastward across the North Atlantic eroded a series of ridges steering Gaston, causing the system to drift north and northeast. Cold water upwelling, concurrent with dry air entrainment, caused Gaston to weaken on August 29,[93] although unexpected re-intensification allowed Gaston to attain its peak winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) for a second time by 03:00 UTC on August 31.[94] Later that day, Gaston began to enter increasingly cool waters and a higher shear environment and slowly degraded: it fell below major hurricane status by 21:00 UTC on August 31,[95] weakened below hurricane intensity by 09:00 UTC on September 2,[96] and degenerated into a remnant low 24 hours later while northwest of the Azores.[97]

Tropical Depression Eight

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 28 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1009 mbar (hPa) |

On August 26, a broad low pressure area formed south of Bermuda,[98] associated with a circulation that absorbed the remnants of Tropical Storm Fiona.[99] It failed to initially develop due to dry air,[100] although the associated thunderstorms produced winds of 35 mph (55 km/h). The system moved generally westward,[98] developing more organized convection on August 27,[101] which increased further the next day. Based on the organization and the system's well-organized center, the NHC initiated advisories on Tropical Depression Eight at 15:00 UTC on August 28, located about 405 mi (655 km) southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. A ridge to the north steered the nascent depression westward into an area of moderate wind shear that precluded initial development.[99] Late on August 28, the center became exposed from the convection.[102] By 24 hours later though, the thunderstorms increased and developed into banding features.[103] On August 28, the NHC issued a tropical storm watch for the Outer Banks of North Carolina from Cape Lookout to Oregon Inlet,[104] which was upgraded to a tropical storm warning on the next day.[103] However, increasing wind shear and its proximity to Hermine prevented it from developing into a tropical storm, and the depression eventually opened up into a trough early on September 1.[105]

Hurricane Hermine

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 28 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 982 mbar (hPa) |

On August 18, the NHC first noted a tropical wave southwest of Cape Verde as a potential area for development.[106] On August 24, the system crossed Guadeloupe into the Caribbean Sea while producing gale force winds.[107][108] Marginal wind shear disrupted the system's organization,[109] and the system crossed the southern Bahamas with scattered convection.[110] While in its developmental stages, the precursor low dropped 3 to 5 in (76 to 127 mm) of rainfall across northern Cuba.[111] In Batabanó on Cuba's southern coast, the southerly winds and 8.5 in (215 mm) of rainfall caused moderate flooding.[112] On August 28, the convection increased and became more organized,[113] and the NHC initiated advisories on Tropical Depression Nine at 21:00 UTC about halfway between the Florida Keys and the north coast of Cuba.[114] On August 31, an impressive burst of thunderstorm activity around the center plus an increase of wind speed to 40 mph (64 km/h) was enough to finally classify the depression as a tropical storm, and was named Hermine.[115] Despite only marginal favorable conditions, Hermine rapidly intensified into a Category 1 hurricane and accelerated northeastwards, nearing the Big Bend area, making it the first hurricane to form in the gulf since Ingrid in 2013.[116] After making landfall on September 2, Hermine's circulation degraded. A few hours after exiting the coast, Hermine weakened into a depression and began extratropical transition. Hermine completed the transition early on September 3, and began restrengthening, as the forward motion of the storm slowed.[citation needed]

Tropical Storm Ian

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

On September 5, the NHC indicated that the development of a tropical cyclone was possible in the East Atlantic over subsequent days.[117] A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa the next morning,[118] slowly coalescing into Tropical Storm Ian by 15:00 UTC on September 12.[119] Steered north and the northeast by an approaching upper-level trough, the cyclone struggled within an environment of high shear, with its low-level center displaced west of its associated convection.[120] An upper-level low became superimposed with the storm's center by late on September 14, yielding a more subtropical-like appearance on conventional satellite.[121] By 09:00 UTC on September 16, however, a small mid-level eye became apparent, and Ian accordingly peaked with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[122] Deep convection dissipated as cold air wrapped into the center, marking Ian's transition into an extratropical cyclone.[123]

Tropical Storm Julia

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 14 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

Early on September 8, a concentrated area of shower and thunderstorm activity developed in association with a broad low east of the Leeward Islands.[124] The disturbance increased in organization as it passed through the northwestern Bahamas late on September 12, but further development was not expected at the time.[125] By 03:00 UTC on September 14, however, the system maintained sufficient organization to be declared Tropical Storm Julia, the first tropical cyclone on record to form over Florida.[126][127] Following formation, the cyclone drifted northwards and then east offshore the Southeastern United States in a weak steering regime. A cyclonic loop occurred as strong westerly air developed in the region. The shear caused Julia to periodically fluctuate in intensity. This was also marked by periodic bursts of convection around the already disorganized center.[128] By 03:00 UTC By September 19, the center of Julia had been devoid of strong convection, as rainbands began to rapidly diminished. By 03:00 UTC that day, Julia degraded into a remnant low. The remnants of the storm continued to drift, bringing more rain to the region.[129]

Parts of North Carolina received as much as a foot of rain, while as much as 18 inches fell in the Hampton Roads area of Virginia. 63 people had to be rescued from their homes, and 61 were evacuated from nursing homes. One million gallons of sewage from Elizabeth City flowed into the Pasquotank River and Charles Creek. The Cashie River in Windsor, North Carolina reached 15 feet on September 22, 2 feet above flood stage. That same day, Gov. Pat McCrory declared a state of emergency in 11 counties. Bertie, Currituck and Hertford Counties in North Carolina closed schools.[130]

Tropical Storm Karl

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 14 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 988 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began monitoring a tropical wave off the western coast of Africa on September 12.[131] Steered west-northwest and then west, it steadily organized while passing through the Cabo Verde Islands, and the wave attained sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression by 15:00 UTC on September 14.[132] The effects of strong shear plagued the cyclone after formation, with its low-level circulation misplaced from the associated shower and thunderstorm activity.[133] By 03:00 UTC on September 16, however, a significant burst of deep convection prompted the depression's upgrade to Tropical Storm Karl.[134] The cyclone continued west for several days across the unfavorable central Atlantic, and it eventually weakened to a tropical depression by 09:00 UTC on September 21.[135] By the next afternoon, a relaxation of strong upper-level winds allowed the system to reattain tropical storm intensity as it curved near Bermuda,[136] and by early on September 25 it attained peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h).[137] Cold air encroached on the low-level circulation by 15:00 UTC that day, marking Karl's transition to an extratropical cyclone.[138]

Tropical Storm Lisa

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 19 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 999 mbar (hPa) |

On September 14, the NHC noted the potential for tropical cyclone development in the East Atlantic later in the week.[139] A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa two days later,[140] developing into a tropical depression by 21:00 UTC on September 19.[141] Then, on September 20, it strengthened to Tropical storm Lisa.[142] At 9:00 UTC September 22, Lisa reached peak intensity of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 999 mbar.[143] The storm started to weaken soon after due to increasing wind shear, but restrengthened a day later.[143] Lisa managed to maintain tropical storm intensity while battling unfavorable conditions until September 23, where at 21:00 UTC the storm weakened to a tropical depression.[144] Lisa became a remnant low at 3:00 UTC on September 25, and the National Hurricane Center issued their final advisory on the system.[145] The remnants of Lisa were monitored for potential regeneration, but the remnants failed to redevelop and dissipated soon after.[146]

Hurricane Matthew

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

Current storm status (1-min mean) | |||

| |||

| As of: | 5:00 a.m. EDT (09:00 UTC) October 9 | ||

| Location: | 34°54′N 75°06′W / 34.9°N 75.1°W ± 20 nm About 30 mi (50 km) SE of Cape Hatteras, NC | ||

| Sustained winds: | 65 kt (75 mph; 120 km/h) (1-min mean) gusting to 80 kt (90 mph; 150 km/h) | ||

| Pressure: | 983 mbar (hPa; 29.03 inHg) | ||

| Movement: | ENE at 12 kt (14 mph; 22 km/h) | ||

| See more detailed information. | |||

On September 22, the NHC highlighted a tropical wave emerging off the western coast of Africa for potential development.[147] The wave moved swiftly westward while coalescing, and although it initially struggled to develop a closed surface circulation, the disturbance acquired sufficient organization to be declared Tropical Storm Matthew by 15:00 UTC on September 28 just southeast of Saint Lucia.[148] Continuing westward under the influence of a mid-level ridge, the storm steadily intensified to attain hurricane intensity by 15:00 UTC on September 29 despite a partially exposed center.[149] The effects of southwesterly wind shear unexpectedly abated late that day, and Matthew began a period of rapid intensification; from a 24-hour period beginning at 03:00 UTC on September 30, the cyclone's maximum winds doubled, from 80 mph (130 km/h) to 160 mph (260 km/h), making Matthew a Category 5 hurricane – the first hurricane of such strength since Hurricane Felix in 2007.[150][151] The storm's small eye became less distinct early on October 1, prompting the NHC to downgrade Matthew to a Category 4 hurricane.[152] {{cn span|Matthew remained a powerful Category 4 hurricane for several days until it was downgraded to a Category 3 hurricane on October 5. However, Matthew restrengthened into a Category 4 hurricane while over the Bahamas on October 6. However, it weakened back to a Category 3 hurricane near the Florida coast due to an eyewall replacement cycle.

One person died in St. Vincent when he was crushed by a boulder.[153] Another person drowned in a river due to heavy rains in Uribia, La Guajira in Colombia.[154] In total, 897 deaths have been attributed to the storm, including 877 in Haiti,[155][156] making it the deadliest Atlantic hurricane since Stan in 2005, which killed more than 1,600 in Central America and Mexico.

Current storm information

As of 5:00 a.m. EDT (09:00 UTC) October 9, Post-Tropical Cyclone Matthew is located within 15 nautical miles of 34°54′N 75°06′W / 34.9°N 75.1°W, about 30 miles (50 km) southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Maximum sustained winds are 65 knots (75 mph; 120 km/h), with gusts up to 80 knots (90 mph; 150 km/h). The minimum barometric pressure is 983 mbar (hPa; 29.03 inHg), and the system is moving east-northeast at 12 knots (14 mph, 22 km/h). Hurricane-force-winds extend outward up to 70 miles (110 km) mainly to the southwest of the center, and tropical-storm-force winds extend outward up to 240 miles (390 km).

For latest official information, see:

- The NHC's latest public advisory on Hurricane Matthew

- The NHC's latest forecast advisory on Hurricane Matthew

Watches and warnings

Template:HurricaneWarningsTable

Hurricane Nicole

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| As of: | 5:00 a.m. AST (09:00 UTC) October 9 | ||

| Location: | 24°18′N 65°42′W / 24.3°N 65.7°W ± 25 nm About 555 mi (895 km) S of Bermuda | ||

| Sustained winds: | 45 kt (50 mph; 85 km/h) (1-min mean) gusting to 55 kt (65 mph; 100 km/h) | ||

| Pressure: | 999 mbar (hPa; 29.50 inHg) | ||

| Movement: | Stationary | ||

| See more detailed information. | |||

On October 1, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave in the central Atlantic for possible tropical development. On October 4, an ASCAT pass revealed the presence of a well-defined surface circulation and winds of up to 50 mph, and the NHC initiated advisories on Tropical Storm Nicole at 15:00 UTC that day.[157] The National Hurricane Center did not expect Nicole to become a hurricane due to moderate to strong west-southwesterly wind shear; however, on October 6, Nicole became a Category 1 hurricane south of Bermuda.[158] Nicole then continued to strengthen into a Category 2 hurricane, thus becoming the first time since 1964 that two hurricanes at or above Category 2 existed in the Western Atlantic Ocean (65°W) simultaneously.[159] However, Nicole rapidly weakened to a tropical storm while it was stationary.[citation needed]

Current storm information

As of 5:00 a.m. AST (09:00 UTC) October 9, Tropical Storm Nicole is located within 25 nautical miles of 24°18′N 65°42′W / 24.3°N 65.7°W, about 555 miles (895 km) south of Bermuda. Maximum sustained winds are 45 knots (50 mph; 85 km/h), with gusts up to 55 knots (65 mph; 100 km/h). The minimum barometric pressure is 999 mbar (hPa; 29.50 inHg), and the system is currently stationary. Tropical-storm-force winds extend outward up to 115 miles (185 km) from the center of Nicole.

For latest official information, see:

- The NHC's latest public advisory on Tropical Storm Nicole

- The NHC's latest forecast advisory on Tropical Storm Nicole

Storm names

The following list of names will be used for named storms that form in the North Atlantic in 2016. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2017. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2022 season. This is the same list used in the 2010 season, with the exception of Ian and Tobias, which replaced Igor and Tomas, respectively.[160] The name Ian was used for the first time this year.

|

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms that have formed in the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 2016 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alex | January 12 – 15 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 981 | Bermuda, Azores | Minimal | (1) | |||

| Bonnie | May 27 – June 5 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1006 | The Bahamas, Southeastern United States | >0.64 | 2 | |||

| Colin | June 5 – 7 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | Yucatán Peninsula, Cuba, East Coast of the United States | 0.01 | 6 | |||

| Danielle | June 19 – 21 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1007 | Yucatán Peninsula, Eastern Mexico | Unknown | 1 | |||

| Earl | August 2 – 6 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 979 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Central America, Mexico | ≥250 | 61 (6) | |||

| Fiona | August 17 – 23 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Gaston | August 22 – September 3 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 956 | Azores | None | None | |||

| Eight | August 28 – September 1 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1009 | North Carolina | None | None | |||

| Hermine | August 28 – September 3 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 982 | Dominican Republic, Cuba, The Bahamas, East Coast of the United States | ≥300.5 | 4 (1) | |||

| Ian | September 12 – 16 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 994 | None | None | None | |||

| Julia | September 14 – 19 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1007 | Southeastern United States | Unknown | None | |||

| Karl | September 14 – 25 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 988 | Cape Verde, Bermuda | Minimal | None | |||

| Lisa | September 19 – 25 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 999 | None | None | None | |||

| Matthew | September 28 – October 9 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 934 | Lesser Antilles, Venezuela, Colombia, Jamaica, Hispaniola, Cuba, Lucayan Archipelago, Southeastern United States | ≥6,000 | 897 | |||

| Nicole | October 4 – Present | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 968 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 15 systems | January 12 – Season ongoing | 160 (260) | 934 | 7,551.15 | 971 (8) | |||||

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- 2016 Pacific hurricane season

- 2016 Pacific typhoon season

- 2016 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2015–16, 2016–17

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2015–16, 2016–17

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2015–16, 2016–17

Footnotes

- ^ The totals represent the sum of the squares for every (sub)tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2016 Atlantic hurricane season/ACE calcs.

References

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ^ a b "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 16, 2015). Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2016 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 5, 2016). April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2016 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ a b http://hurricane.atmos.colostate.edu/forecasts/2016/apr2016/apr2016.pdf

- ^ http://scmss.coastal.edu/sites/default/files/uploaded_files/HUGO_forecast_2016_2.pdf

- ^ "East Coast Should Expect Active Hurricane Season, Researchers Say". 15 April 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Met Office predicts slightly above-average Atlantic hurricane season". Met Office News Blog. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ "Near-normal Atlantic hurricane season is most likely this year". Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ "Pre-Season Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2016" (PDF). Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "EXTENDED RANGE FORECAST OF ATLANTIC SEASONAL HURRICANE ACTIVITY AND LANDFALL STRIKE PROBABILITY FOR 2016" (PDF). Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "2016 WeatherTiger Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook". Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "FORECAST OF ATLANTIC SEASONAL HURRICANE ACTIVITY AND LANDFALL STRIKE PROBABILITY FOR 2016" (PDF). Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ a b Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (July 5, 2016). July Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2016 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (August 5, 2016). August Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2016 (PDF) (Report). London, United Kingdom: Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ "WeatherTiger 2016 Hurricane Season Outlook: August Update". Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Atlantc hurricane season still expected to become strongest since 2012". Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ "WeatherTiger 2016 Hurricane Season Outlook: Mid-season Update". Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (December 11, 2015). "Qualitative Discussion of Atlantic Basin Seasonal Hurricane Activity for 2016" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ a b "Tropical Storm Colin Has Formed in the Gulf of Mexico, Tropical Storm Warnings Issued for Parts of Florida". The Weather Channel. June 5, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Bob Henson (June 6, 2016). "Tropical Storm Colin Becomes Earliest "C" Storm in Atlantic History". San Francisco, California: Weather Underground. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Jeff Masters; Bob Henson (June 20, 2016). "Danielle the Atlantic's Earliest 4th Storm on Record; 115°-120° Heat in SW U.S." San Francisco, California: Weather Underground. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ^ "Monthly Atlantic Tropical Weather Summary". August 1, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ Jeff Masters (August 10, 2016). "Mexico's 2nd Highest Death Toll From an Atlantic Storm Since 1988: 45 Killed in Earl". Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (September 30, 2016). Hurricane Matthew Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Eric Holthaus. "Matthew Could Become One of Haiti's Worst-Ever Hurricanes". The Public Standard. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (September 13, 2016). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Alex (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 2, 3. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ Jonathan Bell (January 8, 2016). "Windy weather affects flights and power". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "Lagoa IAZORESL2". Weather Underground. January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Rare January Hurricane Alex Landfalls in The Azores as a Tropical Storm". Atlanta, Georgia: The Weather Channel. January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Ana Dias Cordeiro and Lusa (January 15, 2016). "Furacão Alex passou a tempestade tropical depois de ter atravessado os Açores". Público (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lusa (January 16, 2016). "Furacão Alex impede socorro da Força Aérea e doente morre". Público (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Eric S. Blake (May 24, 2016). "Special Tropical Weather Outlook 335 pm EDT Tue May 24 2016". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (May 25, 2016). "Special Tropical Weather Outlook 740 pm EDT Wed May 25 2016". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ a b Stacy R. Stewart (May 27, 2016). "Tropical Depression Two Public Advisory Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (May 28, 2016). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Public Advisory Number 5". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (May 29, 2016). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Public Advisory Number 7". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown; Todd B. Kimberlain (May 29, 2016). "Tropical Depression Bonnie Intermediate Advisory Number 7A". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown; Todd B. Kimberlain (May 29, 2016). "Tropical Depression Bonnie Tropical Cyclone Update". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (May 29, 2016). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Bonnie Public Advisory Number 12". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 2, 2016). "Tropical Depression Bonnie Discussion Number 24". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 3, 2016). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Discussion Number 29". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (June 5, 2016). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Bonnie Discussion Number 34". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ Staff writer (May 28, 2016). "Flooding from TD Bonnie prompts closing of portion of I-95 in SC". The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Christal Hayes (May 30, 2016). "Rip currents cause Kissimmee man to drown at beach, officials day". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ WECT Staff (May 31, 2016). "Body of missing swimmer found on Kure Beach". WECT News. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Bonnie causes almost $700K in damages in Jasper County". Savannah Morning News. Jasper County Sun Times. June 9, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 3, 2016). "5-Day Tropical Weather Outlook 800 am EDT Fri Jun 3 2016". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (June 5, 2016). "5-Day Tropical Weather Outlook 800 am EDT Sun Jun 5 2016". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (June 5, 2016). "Tropical Depression Three Discussion Number 1". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (June 5, 2016). "Tropical Storm Colin Public Advisory Number 2". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (June 5, 2016). "Tropical Storm Colin Tropical Cyclone Update". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 6, 2016). "Tropical Storm Colin Discussion Number 4". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (June 6, 2016). "Tropical Storm Colin Discussion Number 7". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven (June 7, 2016). "Tropical Storm Colin Discussion Number 8". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (June 7, 2016). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Colin Discussion Number 10". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Tori Whitley (June 8, 2016). "Tourist Drowns During Colin". WFSU-TV. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "3 possibly 4 dead in Tuesday drownings along Panhandle beaches". Bay County, Florida: WJHG. June 8, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ "3 drown, 1 missing after deadly day at beach". Miaramar Beach, Florida: Northwest Florida Daily News. June 8, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Colin leaves mess across Tampa Bay area". tampabay.com. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven II (September 8, 2016). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Danielle (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Reportan daños por tormenta Danielle en Veracruz" (in Spanish). Veracruz, Mexico: e-consulta Veracruz. June 20, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ^ "Tormenta Danielle causa un muerto en México". El Nuevo Dia (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico. June 21, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (July 28, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (July 28, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 7, 2016). Tropical Storm Earl Special Discussion Number 001 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 3, 2016). Hurricane Earl Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Jack Beven (August 4, 2016). Hurricane Earl Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Jack Beven (August 4, 2016). Hurricane Earl Discussion Number 008 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 5, 2016). Tropical Storm Earl Discussion Number 011 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (August 5, 2016). Tropical Storm Earl Discussion Number 014 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 6, 2016). Tropical Storm Earl Discussion Number 016 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 6, 2016). Remnants of Earl Discussion Number 017 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Eric Chaney (August 2, 2016). "Jamaica, Caymans Bracing for Tropical System That 6 Killed in Dominican Republic". Weather.com.

- ^ Luna, Katheryn (4 August 2016). "Defensa Civil recupera el último cadáver del grupo de los náufragos" (in Spanish). Santo Domingo: Listín Diario. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help); templatestyles stripmarker in|last1=at position 1 (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (August 4, 2016). "Situation Report #1 – August, 04 2016" (PDF). St. Michael, Barbados: ReliefWeb. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ^ "Aumenta a 54 la cifra de muertos por el paso de 'Earl'" (in Spanish). Excelsior. August 16, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (August 17, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (August 16, 2016). Tropical Depression Six Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (August 16, 2016). Tropical Storm Fiona Discussion Number 4 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (August 20, 2016). Tropical Storm Fiona Discussion Number 17 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ Michael J. Brennan (August 21, 2016). Tropical Depression Fiona Public Advisory Number 21 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (August 23, 2016). Post-Tropical Cyclone Fiona Public Advisory Number 27 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (August 17, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (August 17, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg; David P. Roberts (August 22, 2016). Tropical Depression Seven Public Advisory Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (August 22, 2016). Tropical Storm Gaston Public Advisory Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (August 25, 2016). Hurricane Gaston Public Advisory Number 11 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (August 25, 2016). Hurricane Gaston Discussion Number 11 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (August 27, 2016). Tropical Storm Gaston Discussion Number 20 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (August 28, 2016). Hurricane Gaston Public Advisory Number 22 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (August 28, 2016). Hurricane Gaston Public Advisory Number 25 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven II (August 29, 2016). Hurricane Gaston Discussion Number 28 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (August 30, 2016). Hurricane Gaston Public Advisory Number 34 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Michael J. Brennan (August 31, 2016). Hurricane Gaston Public Advisory Number 37 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ David P. Roberts; Stacy R. Stewart (September 2, 2016). Tropical Storm Gaston Public Advisory Number 43 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimerbalin (September 3, 2016). Post-Tropical Cyclone Gaston Public Advisory Number 47 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Robbie Berg (August 27, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Michael Brennan (August 28, 2016). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 26, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ Michael Brennan (August 27, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ Michael Brennan (August 28, 2016). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Eric Blake (August 29, 2016). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ Michael Brennan (August 28, 2016). Tropical Depression Eight Advisory Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ Christopher Landsea (September 1, 2016). Remnants of Eight Discussion Number 16 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (August 18, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Todd Kimberlain (August 24, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Daniel Brown (August 24, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Jack Beven (August 25, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Robbie Berg (August 27, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Lixion Avila (August 27, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ "Temporal de lluvias provoca inundación en una localidad costera" (in Spanish). El Mundo. EFE. August 30, 2016.

- ^ Michael Brennan (August 28, 2016). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Michael Brennan (August 28, 2016). Tropical Depression Nine Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Richard Pasch (August 31, 2016). Tropical Storm HERMINE Public Advisory 12A (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Michael Brennan/Richard Pasch (September 1, 2016). Hurricane HERMINE Update 1:55 CDT (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (September 5, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (September 6, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (September 12, 2016). Tropical Storm Ian Public Advisory Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (September 12, 2016). Tropical Storm Ian Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 13, 2016). Tropical Storm Ian Discussion Number 11 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Michael J. Brennan (September 16, 2016). Tropical Storm Ian Discussion Number 16 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Eric S. Blake (September 16, 2016). Post-Tropical Cyclone Ian Public Advisory Number 17 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 8, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 12, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart; James L. Franklin (September 13, 2016). "Tropical Storm Julia Public Advisory Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Doyle Rice (September 14, 2016). "Tropical Storm Julia first to form over land in Florida". USA Today. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Michael J. Brennan (September 15, 2016). Tropical Depression Julia Discussion Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (September 18, 2016). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Julia Public Advisory Number 21". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "N. Carolina flooding from Julia closes schools, spews sewage". News & Observer. Associated Press. September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 12, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven II (September 14, 2016). Tropical Depression Twelve Public Advisory Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Robbie J. Berg (September 15, 2016). Tropical Depression Twelve Discussion Number 4 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 15, 2016). Tropical Storm Karl Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 21, 2016). Tropical Depression Karl Public Advisory Number 28 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Amy Campbell; Brendon Rubin-Oster; Robbie J. Berg (September 22, 2016). Tropical Storm Karl Discussion Number 34 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 25, 2016). Tropical Storm Karl Public Advisory Number 44 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (September 25, 2016). Post-Tropical Cyclone Karl Discussion Number 45 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (September 14, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven II (September 16, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 19, 2016). Tropical Depression Thirteen Public Advisory Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ "Tropical Storm LISA". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ^ a b "Tropical Storm LISA". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ^ "Tropical Depression LISA". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ^ "Post-Tropical Cyclone LISA". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (September 27, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Michael J. Brennan (September 22, 2016). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown (September 28, 2016). Tropical Storm Matthew Public Advisory Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ Daniel P. Brown; Richard J. Pasch (September 29, 2016). Hurricane Matthew Intermediate Advisory Number 5A (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 29, 2016). Hurricane Matthew Public Advisory Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (September 30, 2016). Hurricane Matthew Public Advisory Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ John L. Beven II (October 1, 2016). Hurricane Matthew Discussion Number 13 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ^ Domenica Davis (September 29, 2016). "Matthew blamed for 1 death in Leeward Islands". KSBW. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Huracán Matthew se fortalece y aumenta a categoría cuatro" (in Spanish). Noticias Caracol. September 30, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Carswell, Simon. "Hurricane Matthew kills 140, spurs mass Florida evacuation". The Irish Times. Dublin, Ireland. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Wright, Pam. "Hurricane Matthew Kills At Least 478 in Haiti: 'The Situation Is Catastrophic,' Says Haitian President". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Pasch, Forecaster. "Tropical Storm Nicole Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Pasch, Forecaster. "Hurricane Nicole Special Discussion Number 10". National Hurricane Center. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2016/al15/al152016.discus.012.shtml

- ^ Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 11, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.