Counterattack: Difference between revisions

m Battle of Austerlitz Wikipedia link |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

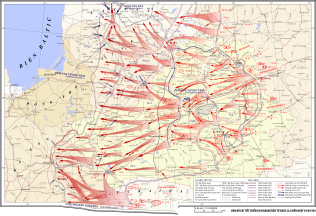

[[File:Battle_of_Austerlitz,_Situation_at_1800,_1_December_1805.png|thumb|282x282px|Map depicting the famous counterattack that took place at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805.]] |

[[File:Battle_of_Austerlitz,_Situation_at_1800,_1_December_1805.png|thumb|282x282px|Map depicting the famous counterattack that took place at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805.]] |

||

Another military battle that utilized the counter attack tactic was the [[Battle of Austerlitz]] on December 2, 1805. While fighting the |

Another military battle that utilized the counter attack tactic was the [[Battle of Austerlitz]] on December 2, 1805. While fighting the Austrian and Russian armies, Napoleon purposely made it seem as if his men were weak from the fighting in several cases.<ref name=":3">{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/260090494|title=1805: Austerlitz : Napoleon and the destruction of the third coalition|last=Robert.|first=Goetz,|date=2005-01-01|publisher=Stackpole Books|isbn=1853676446|oclc=260090494}}</ref> Napoleon had his men retreat in an attempt to lure the Allies to battle.<ref name=":3" /> He purposely left his right flank open and vulnerable.<ref name=":3" /> This deceived the Allies into attacking and the Allies fell into [[Napoleon]]'s trap.<ref name=":3" /> When the Allied troops went to attack Napoleon’s right flank, Napoleon quickly filled up the right flank so the attack was not effective.<ref name=":3" /> However, on the Allied side, a large gap was left open in the middle of the Allied front line due to troops leaving to attack the French right flank.<ref name=":3" /> Noticing the large hole in the middle of the Allied lines, Napoleon attacked the middle and had his forces also flank around both sides, eventually surrounding the Allies.<ref name=":3" /> With the Allies completely surrounded, the battle was over.<ref name=":3" /> The Battle of Austerlitz was a successful counterattack because the French army defended off the Allied attack and quickly defeated the Allies.<ref name=":3" /> Napoleon deceived the Allies.<ref name=":3" /> He made his men seem weak and near defeat. <ref name=":3" /> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 12:45, 4 July 2017

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games".[1] The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek to regain lost ground or destroy the attacking enemy (this may take the form of an opposing sports team or military units).[1][2][3]

A saying, attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte illustrate the tactical importance of the counterattack : "the greatest danger occurs at the moment of victory". In the same spirit, in his Battle Studies, Ardant du Pic noticed that "he, general or mere captain, who employs every one in the storming of a position can be sure of seeing it retaken by an organised counter-attack of four men and a corporal".[4]

A counterattack is a military tactic that occurs when one side successfully defends off the enemy’s attack and begins to push the enemy back with an attack of its own. In order to perform a successful counterattack, the defending side must quickly and decisively strike the enemy after defending, with the objective of shocking and overwhelming the enemy.[5] The main concept of the counterattack is to catch the enemy by surprise.[5] Many historical counterattacks were successful due to the fact that the enemy was off guard and not expecting the counter attack. [5]

Ancient Roots of the Counterattack

The counterattack tactic was highlighted in Sun Tzu’s, The Art of War.[6] Written in 5 B.C, The Art of War serves as a guide on warfare and has been influential to the tactics used during war even to this day. In chapter 3, the book focusses on “stratagem” and goes over how to properly conduct a counter attack.[6] Sun Tzu states, “Thus the highest form of generalship is to balk the enemy’s plans; the next best is to prevent the junction of the enemy’s forces”.[6] This quote advises one to wait out the enemy and conduct a counterattack when the time is right. It states that the best strategy is to stay one step ahead of the enemy, and know the enemy’s next move. Thus keeping a general always prepared for the enemy’s move, leaving opportunity for a counterattack.[6]

Analyzing Historical Counterattacks

In the past, there have been many notable counterattacks which have changed the course of a war. To be specific, Operation Bagration and the Battle of Austerlitz are good examples of the proper execution of a counterattack.

Operation Bagration

One of the largest scale counter attacks in history is Operation Bagration, during World War II. The counter attack successively put the Red army on the offensive in the Eastern Front after Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa.[7] The Soviet counterattack focussed on Belorussia, where Hitler placed heavily placed Luftwaffe, infantry, and Panzer divisions, called the Army Group Centre.[7] Before the counter attack began, the Soviet Union fooled Nazi military leaders into believing that the attack would come further down south, near Ukraine.[7] The Red Army set up fake army camps along Ukraine to make it it appear that Ukraine would be point of Soviet invasion.[7] After German reconnaissance planes reported soviet troop concentration near Ukraine, panzer and infantry divisions were sent to Ukraine, leaving Belorussia vulnerable. Prior to the attack, partisan groups in German controlled territory were instructed to destroyed German railroads thus limiting German transportation of supplies furthering weakening the German Army Centre in Ukraine.[7] On June 22, 1944, the attack on Belarus began. The Soviets attacked with 1.7 million troops, seriously overwhelming and shocking the Germans.[7] On July 3, The Army captured Minsk and later liberated the rest of Belorussia weeks later. Operation Bagration was successful because the Red Army caught the Nazi forces in Belorussia off guard.[7] Through the element of deception, The Army Group Centre in Belorussia was not expecting the attack. The attack was expected to come in Ukraine and because of this, the German troops in Belarus were not prepared for the Soviet attack. Because the Red Army attacked with 1.7 million troops, German forces in Belorussia were not expecting an attack of such strength; the Germans were off guard, disorientated and unorganized due to lack of preparedness.[7] The attack was quick and overwhelming and Minsk fell to the Red Army in just a few days. Operation Bagration was a huge Soviet success. After Belorussia fell, there was a direct line to Berlin. After Operation Bagration, the Red Army began to liberate territory that was taken by the Wehrmacht. [7]

Battle of Austerlitz

Another military battle that utilized the counter attack tactic was the Battle of Austerlitz on December 2, 1805. While fighting the Austrian and Russian armies, Napoleon purposely made it seem as if his men were weak from the fighting in several cases.[8] Napoleon had his men retreat in an attempt to lure the Allies to battle.[8] He purposely left his right flank open and vulnerable.[8] This deceived the Allies into attacking and the Allies fell into Napoleon's trap.[8] When the Allied troops went to attack Napoleon’s right flank, Napoleon quickly filled up the right flank so the attack was not effective.[8] However, on the Allied side, a large gap was left open in the middle of the Allied front line due to troops leaving to attack the French right flank.[8] Noticing the large hole in the middle of the Allied lines, Napoleon attacked the middle and had his forces also flank around both sides, eventually surrounding the Allies.[8] With the Allies completely surrounded, the battle was over.[8] The Battle of Austerlitz was a successful counterattack because the French army defended off the Allied attack and quickly defeated the Allies.[8] Napoleon deceived the Allies.[8] He made his men seem weak and near defeat. [8]

See also

- Counter-offensive

- Battleplan (documentary TV series)

Notes and references

- ^ a b Staff. "counterdeception". DTIC Online. DEFENSE TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

year: Unknown

- ^ Tom Cohen (19 December 2010). "McConnell leads GOP counter-attack against START pact". Cable News Network. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Tim Vickery (27 July 2011). "Uruguay's momentum, Paraguay's bumpy road, more Copa America". SI.com. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ Ardant du Picq, 'Battle Studies'

- ^ a b c Pike, John. "A View On Counterattacks In The Defensive Scheme Of Maneuver". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d B., Griffith, Samuel (1 January 2000). The art of war. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195014761. OCLC 868200458.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i E.,, Glantz, Mary. Battle for Belorussia : the Red Army's forgotten campaign of October 1943-April 1944. ISBN 9780700623297. OCLC 947149001.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Robert., Goetz, (1 January 2005). 1805: Austerlitz : Napoleon and the destruction of the third coalition. Stackpole Books. ISBN 1853676446. OCLC 260090494.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Bruce Schneier (2003). Beyond Fear. Springer. pp. 173–175. ISBN 9780387026206.

- Glover S. Johns (2002). The Clay Pigeons of St. Lo. Stackpole Books. pp. 174–175. ISBN 9780811726047.