Hiltgunt Zassenhaus: Difference between revisions

c/e |

Rescuing 3 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

In autumn 1940, Zassenhaus was employed as interpreter at the German office for the censorship of letters. She resigned this job in 1942 and started studying medicine in Hamburg.<ref name=kl-hz>{{cite encyclopedia|last=Hjeltnes|first=Guri|authorlink=Guri Hjeltnes |editors=Dahl, Hjeltnes Nøkleby, Ringdal, Sørensen |encyclopedia=[[Norsk krigsleksikon 1940-45]]|title=Zassenhaus, Hiltgunt |page=454 |language=Norwegian |url=http://mediabase1.uib.no/krigslex/x-y-z/x-z.html#zassenhaus-hiltgunt |accessdate=10 July 2009 |year=1995 |publisher=Cappelen |location=Oslo |isbn=82-02-14138-9 }}</ref> Later in 1942, she was asked by the [[Staatsanwaltschaft|prosecutor]] in Hamburg to censor letters to and from Norwegian prisoners in the ''[[Prisons in Germany#Previous types of prisons|Zuchthaus]]'' in [[Fuhlsbüttel]], Hamburg.<ref name=brunvand>{{cite book |title=Smil og tårer i tukthus |first=Olav |last=Brunvand |authorlink=Olav Brunvand |pages=15–28 |language=Norwegian |publisher=Tiden |location=Oslo |year=1968}}</ref> She initially refused, but after further pressure, she accepted on the condition that she be allowed to work independently.<ref name=ottosen-h/> Instead of censoring the mail, she added messages urging the recipients to send food or warm clothing.<ref name=Sun1985>{{cite news |title=It Had To Be Done |author=Patrick Ercolano |newspaper=Baltimore Sun |date=22 September 1985 |url=http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013500/013570/pdf/sun22sept1985.pdf}}</ref> |

In autumn 1940, Zassenhaus was employed as interpreter at the German office for the censorship of letters. She resigned this job in 1942 and started studying medicine in Hamburg.<ref name=kl-hz>{{cite encyclopedia|last=Hjeltnes|first=Guri|authorlink=Guri Hjeltnes |editors=Dahl, Hjeltnes Nøkleby, Ringdal, Sørensen |encyclopedia=[[Norsk krigsleksikon 1940-45]]|title=Zassenhaus, Hiltgunt |page=454 |language=Norwegian |url=http://mediabase1.uib.no/krigslex/x-y-z/x-z.html#zassenhaus-hiltgunt |accessdate=10 July 2009 |year=1995 |publisher=Cappelen |location=Oslo |isbn=82-02-14138-9 }}</ref> Later in 1942, she was asked by the [[Staatsanwaltschaft|prosecutor]] in Hamburg to censor letters to and from Norwegian prisoners in the ''[[Prisons in Germany#Previous types of prisons|Zuchthaus]]'' in [[Fuhlsbüttel]], Hamburg.<ref name=brunvand>{{cite book |title=Smil og tårer i tukthus |first=Olav |last=Brunvand |authorlink=Olav Brunvand |pages=15–28 |language=Norwegian |publisher=Tiden |location=Oslo |year=1968}}</ref> She initially refused, but after further pressure, she accepted on the condition that she be allowed to work independently.<ref name=ottosen-h/> Instead of censoring the mail, she added messages urging the recipients to send food or warm clothing.<ref name=Sun1985>{{cite news |title=It Had To Be Done |author=Patrick Ercolano |newspaper=Baltimore Sun |date=22 September 1985 |url=http://www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013500/013570/pdf/sun22sept1985.pdf}}</ref> |

||

According to the German prison rules, the prisoners were allowed to receive regular visits, and the [[Norwegian Church Abroad|Norwegian priests in Hamburg]] were authorized to visit the prisoners on behalf of their families.<ref name=kl-prest-hamburg>{{cite encyclopedia|last=Hjeltnes|first=Guri|authorlink=Guri Hjeltnes |editors=Dahl, Hjeltnes, Nøkleby, Ringdal, Sørensen |encyclopedia=Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45 |language=Norwegian |

According to the German prison rules, the prisoners were allowed to receive regular visits, and the [[Norwegian Church Abroad|Norwegian priests in Hamburg]] were authorized to visit the prisoners on behalf of their families.<ref name=kl-prest-hamburg>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Hjeltnes |first=Guri |authorlink=Guri Hjeltnes |editors=Dahl, Hjeltnes, Nøkleby, Ringdal, Sørensen |encyclopedia=Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45 |language=Norwegian |title=sjømannsprestene i Hamburg |page=381 |url=http://mediabase1.uib.no/krigslex/s/s4.html#sjomannsprestene-i |accessdate=10 July 2009 |year=1995 |publisher=Cappelen |location=Oslo |isbn=82-02-14138-9 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110525035438/http://mediabase1.uib.no/krigslex/s/s4.html#sjomannsprestene-i |archivedate=25 May 2011 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> She was assigned to interpret for and watch the priests during their visits.<ref name=ottosen-h/> Later, she also interpreted for Danish priests and prisoners. She began smuggling in food, medicine, and writing materials.<ref name=Sun1985/> She was aided by the suspicion of the authorities that, because of her position in the Department of Justice, she was a member of the [[Gestapo]].<ref name=Sun1985/> |

||

Towards the end of the war, the prisoners were moved to various prisons all over Germany, and the visits, to more than 1,000 Scandinavian prisoners scattered in 52 prisons,<ref name=Huggins/> required long journeys.<ref name=ottosen-h/><ref name=h-abendblatt/> Zassenhaus maintained her own records in order to keep track of where the prisoners were being held; these files became important for the later evacuation by the [[White Buses]] in 1945.<ref name=baltimore-sun>{{cite web|title=Dr. Hiltgunt Margret Zassenhaus |url=http://www.zionbaltimore.org/events_2004_hiltgunt_zassenhaus_memorial.htm |year=2004 |first=Jean |last=Packard |work=The Baltimore Sun |accessdate=10 July 2009 }}</ref><ref name=shcj/><ref name=kl-hvite-busser>{{cite encyclopedia|last=Hjeltnes|first=Guri|authorlink=Guri Hjeltnes |editors=Dahl, Hjeltnes, Nøkleby, Ringdal, Sørensen |language=Norwegian |encyclopedia=Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45|title=hvite busser |pages=185–186 |url=http://mediabase1.uib.no/krigslex/h/h7.html#hvite-busser |accessdate=10 July 2009 |year=1995 |publisher=Cappelen |location=Oslo |isbn=82-02-14138-9 }}</ref> |

Towards the end of the war, the prisoners were moved to various prisons all over Germany, and the visits, to more than 1,000 Scandinavian prisoners scattered in 52 prisons,<ref name=Huggins/> required long journeys.<ref name=ottosen-h/><ref name=h-abendblatt/> Zassenhaus maintained her own records in order to keep track of where the prisoners were being held; these files became important for the later evacuation by the [[White Buses]] in 1945.<ref name=baltimore-sun>{{cite web |title=Dr. Hiltgunt Margret Zassenhaus |url=http://www.zionbaltimore.org/events_2004_hiltgunt_zassenhaus_memorial.htm |year=2004 |first=Jean |last=Packard |work=The Baltimore Sun |accessdate=10 July 2009 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090930193534/http://www.zionbaltimore.org/events_2004_hiltgunt_zassenhaus_memorial.htm |archivedate=30 September 2009 |df=dmy-all }}</ref><ref name=shcj/><ref name=kl-hvite-busser>{{cite encyclopedia|last=Hjeltnes|first=Guri|authorlink=Guri Hjeltnes |editors=Dahl, Hjeltnes, Nøkleby, Ringdal, Sørensen |language=Norwegian |encyclopedia=Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45|title=hvite busser |pages=185–186 |url=http://mediabase1.uib.no/krigslex/h/h7.html#hvite-busser |accessdate=10 July 2009 |year=1995 |publisher=Cappelen |location=Oslo |isbn=82-02-14138-9 }}</ref> |

||

With the war in Europe nearing its end, Zassenhaus learned of "Day X", when all political prisoners were to be killed.<ref name=Huggins/> She passed on her information and her files of prisoner locations to either the [[Red Cross]]<ref name=Huggins/> or Swedish Count Bernadotte.<ref name=Sun1974/> A deal was negotiated; 1200 Scandinavian prisoners were freed and transported out of Germany.<ref name=Huggins/><ref name=Sun1974/> |

With the war in Europe nearing its end, Zassenhaus learned of "Day X", when all political prisoners were to be killed.<ref name=Huggins/> She passed on her information and her files of prisoner locations to either the [[Red Cross]]<ref name=Huggins/> or Swedish Count Bernadotte.<ref name=Sun1974/> A deal was negotiated; 1200 Scandinavian prisoners were freed and transported out of Germany.<ref name=Huggins/><ref name=Sun1974/> |

||

Zassenhaus wrote about her experiences during the war in her 1947 book ''Halt Wacht im Dunkel''.<ref name=h-abendblatt>{{cite web|title=Mutiger "Engel der Gefangenen" |url=http://www.abendblatt.de/ratgeber/extra-journal/article368276/Mutiger-Engel-der-Gefangenen.html |date=6 December 2005 |language=German |first=Klaus |last=Witzeling |work=Hamburger Abendblatt |accessdate=10 July 2009 }}</ref> An English translation, ''Walls'', was published in 1974.<ref name=baltimore-sun/> In 1978, she was featured in a British television series called ''Women in Courage'' about four women who defied the Nazis. It was produced by [[Peter Morley (filmmaker)|Peter Morley]],<ref>Peter Morley, [http://static.bafta.org/files/peter-morley-a-life-rewound-part-4-194.pdf ''Peter Morley – A Life Rewound'' Part 4] (PDF) British Academy of Film and Television Arts (2010), p. 251. Retrieved 29 September 2011</ref> himself a German refugee. The other women were [[Maria Rutkiewicz]], a Polish woman; [[Sigrid Helliesen Lund]], a Norwegian; and [[Mary Lindell]], a British woman. |

Zassenhaus wrote about her experiences during the war in her 1947 book ''Halt Wacht im Dunkel''.<ref name=h-abendblatt>{{cite web|title=Mutiger "Engel der Gefangenen" |url=http://www.abendblatt.de/ratgeber/extra-journal/article368276/Mutiger-Engel-der-Gefangenen.html |date=6 December 2005 |language=German |first=Klaus |last=Witzeling |work=Hamburger Abendblatt |accessdate=10 July 2009 }}</ref> An English translation, ''Walls'', was published in 1974.<ref name=baltimore-sun/> In 1978, she was featured in a British television series called ''Women in Courage'' about four women who defied the Nazis. It was produced by [[Peter Morley (filmmaker)|Peter Morley]],<ref>Peter Morley, [http://static.bafta.org/files/peter-morley-a-life-rewound-part-4-194.pdf ''Peter Morley – A Life Rewound'' Part 4] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140222202024/http://static.bafta.org/files/peter-morley-a-life-rewound-part-4-194.pdf |date=22 February 2014 }} (PDF) British Academy of Film and Television Arts (2010), p. 251. Retrieved 29 September 2011</ref> himself a German refugee. The other women were [[Maria Rutkiewicz]], a Polish woman; [[Sigrid Helliesen Lund]], a Norwegian; and [[Mary Lindell]], a British woman. |

||

==Later years/death== |

==Later years/death== |

||

Revision as of 02:15, 4 November 2017

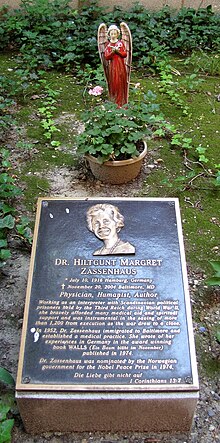

Hiltgunt Margret Zassenhaus (10 July 1916 – 20 November 2004) was a German philologist who worked as an interpreter in Hamburg, Germany during World War II, and later as a physician in the United States. She was honoured for her efforts to aid prisoners in Nazi Germany during World War II.

Early life

Hiltgunt Zassenhaus was born in Hamburg to Julius H. and Margret Ziegler Zassenhaus.[1] Her father was a historian and school principal who lost his job when the Nazi regime came to power in 1933.[2][3] Her brothers were the mathematician Hans (known for the butterfly lemma and the Zassenhaus group), and physicians Günther and Willfried.[3]

Following a bicycling holiday in Denmark in 1933, she decided to study philology, specializing in the Scandinavian languages. She graduated from the University of Hamburg with a degree in Norwegian and Danish language[4] in 1939[2] and continued her language studies at the University of Copenhagen.

World War II

In autumn 1940, Zassenhaus was employed as interpreter at the German office for the censorship of letters. She resigned this job in 1942 and started studying medicine in Hamburg.[5] Later in 1942, she was asked by the prosecutor in Hamburg to censor letters to and from Norwegian prisoners in the Zuchthaus in Fuhlsbüttel, Hamburg.[6] She initially refused, but after further pressure, she accepted on the condition that she be allowed to work independently.[4] Instead of censoring the mail, she added messages urging the recipients to send food or warm clothing.[7]

According to the German prison rules, the prisoners were allowed to receive regular visits, and the Norwegian priests in Hamburg were authorized to visit the prisoners on behalf of their families.[8] She was assigned to interpret for and watch the priests during their visits.[4] Later, she also interpreted for Danish priests and prisoners. She began smuggling in food, medicine, and writing materials.[7] She was aided by the suspicion of the authorities that, because of her position in the Department of Justice, she was a member of the Gestapo.[7]

Towards the end of the war, the prisoners were moved to various prisons all over Germany, and the visits, to more than 1,000 Scandinavian prisoners scattered in 52 prisons,[1] required long journeys.[4][9] Zassenhaus maintained her own records in order to keep track of where the prisoners were being held; these files became important for the later evacuation by the White Buses in 1945.[2][3][10]

With the war in Europe nearing its end, Zassenhaus learned of "Day X", when all political prisoners were to be killed.[1] She passed on her information and her files of prisoner locations to either the Red Cross[1] or Swedish Count Bernadotte.[11] A deal was negotiated; 1200 Scandinavian prisoners were freed and transported out of Germany.[1][11]

Zassenhaus wrote about her experiences during the war in her 1947 book Halt Wacht im Dunkel.[9] An English translation, Walls, was published in 1974.[2] In 1978, she was featured in a British television series called Women in Courage about four women who defied the Nazis. It was produced by Peter Morley,[12] himself a German refugee. The other women were Maria Rutkiewicz, a Polish woman; Sigrid Helliesen Lund, a Norwegian; and Mary Lindell, a British woman.

Later years/death

After the war, Zassenhaus was unable to complete her studies at the University of Hamburg due to the damage inflicted on the city. As Germans had been prohibited from entering Denmark, Zassenhaus was smuggled into the country in 1947 in a fish truck.[13]

Afterward, the Danish parliament passed a special law to legitimize her immigration.[13] She continued her medical studies at the University of Bergen, where she finished the first part of the course, and finally graduated as a physician from the University of Copenhagen.[4] She emigrated to Baltimore in 1952, where she worked as a practising physician.[4]

Hiltgunt Zassenhaus died on 20 November 2004, aged 88.[14]

Honours

Zassenhaus is the only person from Germany decorated with the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav for her activities during World War II.[6] She was also awarded the Red Cross Medal, the Danish Order of the Dannebrog,[2] the German Bundesverdienstkreuz,[9] and the British Cross of the Order of Merit.[2] In 1974, the Norwegian government nominated her for the Nobel Peace Prize.[11]

References

- ^ a b c d e Amy Huggins. "Hiltgunt Margret Zassenhaus, M.D. (1916–2004)". Maryland State Archives.

- ^ a b c d e f Packard, Jean (2004). "Dr. Hiltgunt Margret Zassenhaus". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Schjølberg, Oddvar. "Hiltgunt Zassenhaus" (in Norwegian). Travel For Peace AS. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Ottosen, Kristian (1993). "Hiltgunt". Bak lås og slå (in Norwegian) (1995 ed.). Oslo: Aschehoug. pp. 368–380. ISBN 82-03-26079-9.

- ^ Hjeltnes, Guri (1995). "Zassenhaus, Hiltgunt". Norsk krigsleksikon 1940-45 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Cappelen. p. 454. ISBN 82-02-14138-9. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Brunvand, Olav (1968). Smil og tårer i tukthus (in Norwegian). Oslo: Tiden. pp. 15–28.

- ^ a b c Patrick Ercolano (22 September 1985). "It Had To Be Done" (PDF). Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Hjeltnes, Guri (1995). "sjømannsprestene i Hamburg". Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Cappelen. p. 381. ISBN 82-02-14138-9. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Witzeling, Klaus (6 December 2005). "Mutiger "Engel der Gefangenen"". Hamburger Abendblatt (in German). Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ Hjeltnes, Guri (1995). "hvite busser". Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Cappelen. pp. 185–186. ISBN 82-02-14138-9. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Michael P. Weiskopf (11 February 1974). "Dr. Zassenhaus, of Towson, named Nobel candidate" (PDF). Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Peter Morley, Peter Morley – A Life Rewound Part 4 Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) British Academy of Film and Television Arts (2010), p. 251. Retrieved 29 September 2011

- ^ a b John Dorsey (25 September 1977). "'Life is what you put into it'" (PDF). Baltimore Sun.

- ^ "Zassenhaus, Dr Hiltgunt M. (obituary)". Baltimore Sun. 8 December 2004.

- 1916 births

- 2004 deaths

- German people of World War II

- Interpreters

- German philologists

- German physicians

- German women writers

- German expatriates in Norway

- German expatriates in Denmark

- German expatriates in the United States

- People from Hamburg

- 20th-century translators

- 20th-century women writers

- 20th-century writers

- Recipients of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Knights of the Order of the Dannebrog