Shardeloes: Difference between revisions

added Category:Buildings by Stiff Leadbetter using HotCat |

|||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

==Design and construction== |

==Design and construction== |

||

The architect and builder was [[Stiff Leadbetter]]; designs for interior decorations were provided by [[Robert Adam]] from 1761.<ref>Shardeloes Papers of the 17th and 18th Centuries. G.Eland (ed). Oxford University Press 1947</ref> Built in the [[Palladian]] style, of [[stucco]]ed brick, the mansion is nine [[bay]]s long by seven bays deep. It was constructed with the [[piano nobile]] on the ground floor and a [[Mezzanine (architecture)|mezzanine]] above. The north facade has a large [[portico]] of [[Corinthian order|Corinthian]] columns. The terminating windows of the piano nobile are [[pediment]]ed and recessed into shallow niches, as are the end bays of the east front. The roof, typically for the palladian style, is hidden by a [[balustrade]]. The original plans of the house by Leadbetter show a design closer in appearance to [[Holkham Hall]], with square end towers. Adam cancelled this idea, but embellished the front with the portico. |

The architect and builder was [[Stiff Leadbetter]]; designs for interior decorations were provided by [[Robert Adam]] from 1761.<ref>Shardeloes Papers of the 17th and 18th Centuries. G.Eland (ed). Oxford University Press 1947</ref> Built in the [[Palladian]] style, of [[stucco]]ed brick, the mansion is nine [[bay (architecture)|bay]]s long by seven bays deep. It was constructed with the [[piano nobile]] on the ground floor and a [[Mezzanine (architecture)|mezzanine]] above. The north facade has a large [[portico]] of [[Corinthian order|Corinthian]] columns. The terminating windows of the piano nobile are [[pediment]]ed and recessed into shallow niches, as are the end bays of the east front. The roof, typically for the palladian style, is hidden by a [[balustrade]]. The original plans of the house by Leadbetter show a design closer in appearance to [[Holkham Hall]], with square end towers. Adam cancelled this idea, but embellished the front with the portico. |

||

The interior of the house has fine ornamental [[plaster]] work by [[Joseph Rose]].<ref>Detailed existing bills from Joseph Rose, 1761-63, totalling £1,139 18s 0d, are noted by Geoffrey Beard, ''Decorative Plasterwork in Great Britain'' 1975:244</ref> The entrance hall by Adam has fluted [[Doric order|Doric]] [[pilaster]]s and massive doorcases in the north and south walls. The dining room has stucco panels and an oval panel in the ceiling. The library was designed by [[James Wyatt]] in a [[classicism|classical]] style and has painted panels by [[Biagio Rebecca]]. [[Nikolaus Pevsner]] describes the staircase as "surprisingly small."<ref>Pevsner, ''Buckinghamshire''. [[Penguin Books]], 1960.</ref> Pevsner for once rather misses the point: as the house was designed, all rooms of importance, including the bedrooms, were on the principal ground floor; thus, there was no need for a grand staircase, as no grandee would ever need to ascend to the secondary floor above. [[Blenheim Palace]] is another house with a small staircase for the same reason. |

The interior of the house has fine ornamental [[plaster]] work by [[Joseph Rose]].<ref>Detailed existing bills from Joseph Rose, 1761-63, totalling £1,139 18s 0d, are noted by Geoffrey Beard, ''Decorative Plasterwork in Great Britain'' 1975:244</ref> The entrance hall by Adam has fluted [[Doric order|Doric]] [[pilaster]]s and massive doorcases in the north and south walls. The dining room has stucco panels and an oval panel in the ceiling. The library was designed by [[James Wyatt]] in a [[classicism|classical]] style and has painted panels by [[Biagio Rebecca]]. [[Nikolaus Pevsner]] describes the staircase as "surprisingly small."<ref>Pevsner, ''Buckinghamshire''. [[Penguin Books]], 1960.</ref> Pevsner for once rather misses the point: as the house was designed, all rooms of importance, including the bedrooms, were on the principal ground floor; thus, there was no need for a grand staircase, as no grandee would ever need to ascend to the secondary floor above. [[Blenheim Palace]] is another house with a small staircase for the same reason. |

||

Revision as of 18:51, 29 August 2018

| Shardeloes | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Country house |

| Architectural style | Palladian |

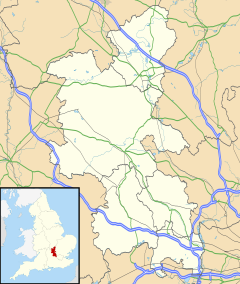

| Location | Near Amersham, Buckinghamshire |

| Coordinates | 51°40′17″N 0°38′40″W / 51.67139°N 0.64444°W |

| Construction started | 1758 |

| Completed | 1766 |

| Client | William Drake, Sr. (1723–1796) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Stiff Leadbetter |

| Other designers | Robert Adam (interiors) Humphry Repton (gardens) |

Shardeloes is a large 18th century country house located one mile west of Amersham in Buckinghamshire, England, UK (grid reference SU937978). A previous manor house on the site was demolished and the present building constructed between 1758 and 1766[1] for William Drake, Sr., the Member of Parliament for Amersham. Shardeloes is a Grade I listed building.[1]

Design and construction

The architect and builder was Stiff Leadbetter; designs for interior decorations were provided by Robert Adam from 1761.[2] Built in the Palladian style, of stuccoed brick, the mansion is nine bays long by seven bays deep. It was constructed with the piano nobile on the ground floor and a mezzanine above. The north facade has a large portico of Corinthian columns. The terminating windows of the piano nobile are pedimented and recessed into shallow niches, as are the end bays of the east front. The roof, typically for the palladian style, is hidden by a balustrade. The original plans of the house by Leadbetter show a design closer in appearance to Holkham Hall, with square end towers. Adam cancelled this idea, but embellished the front with the portico.

The interior of the house has fine ornamental plaster work by Joseph Rose.[3] The entrance hall by Adam has fluted Doric pilasters and massive doorcases in the north and south walls. The dining room has stucco panels and an oval panel in the ceiling. The library was designed by James Wyatt in a classical style and has painted panels by Biagio Rebecca. Nikolaus Pevsner describes the staircase as "surprisingly small."[4] Pevsner for once rather misses the point: as the house was designed, all rooms of importance, including the bedrooms, were on the principal ground floor; thus, there was no need for a grand staircase, as no grandee would ever need to ascend to the secondary floor above. Blenheim Palace is another house with a small staircase for the same reason.

The house is flanked to the west by a service block and stable yard of the same period as the mansion, complete with clock tower. The stable yard is entered through five archways; the rectangular building has projecting wings and a pitched roof.

Grounds

Humphry Repton was commissioned to lay out the grounds in the classical English landscape fashion, in the lee of the hill upon which the mansion stands. Repton dammed the River Misbourne to form a lake.

Recent history

The mansion remained the ancestral home of the Tyrwhitt-Drake family until the Second World War, when the house was requisitioned as a maternity hospital for evacuated pregnant women from London; some three thousand children were born there, including lyricist Sir Tim Rice in 1944 and Thomas Willatt.[5] Following the war the house seemed destined to become one of the thousands of country houses being demolished, until a local conservation society, the Amersham Society, assisted by the Council for the Protection of Rural England fought a prolonged battle to save the house: eventually a preservation order was put on the building preventing its demolition. Although inhabited in parts, the building fell into a state of neglect through the 1960s and was eventually purchased in the early 1970s by local property developer Richard Watson. His company, Landstone Limited, completed a comprehensive renovation of the building and converted unused parts into further apartments. Shardeloes today is a complex of private flats; the principal reception rooms are preserved as common rooms for the residents.

References

- ^ a b Historic England. "Shardeloes, Amersham (1238040)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Shardeloes Papers of the 17th and 18th Centuries. G.Eland (ed). Oxford University Press 1947

- ^ Detailed existing bills from Joseph Rose, 1761-63, totalling £1,139 18s 0d, are noted by Geoffrey Beard, Decorative Plasterwork in Great Britain 1975:244

- ^ Pevsner, Buckinghamshire. Penguin Books, 1960.

- ^ Tim Rice (1999). Oh, What a Circus: The Autobiography. Coronet Books. ISBN 0-340-65459-7.