Bhimbetka rock shelters: Difference between revisions

per WP:BRD revert to previous consensus until the question is resolved on the talk page |

→Rock art and paintings: shift images up, upright one |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

== Rock art and paintings == |

== Rock art and paintings == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

The rock shelters and caves of Bhimbetka have a large number of paintings. The oldest paintings are found to be 30,000 years old, but some of the geometric figures date to as recently as the [[Middle Ages|medieval period]]. The colors used are vegetable colors which have endured through time because the drawings were generally made deep inside a niche or on inner walls. The drawings and paintings can be classified under seven different periods. |

The rock shelters and caves of Bhimbetka have a large number of paintings. The oldest paintings are found to be 30,000 years old, but some of the geometric figures date to as recently as the [[Middle Ages|medieval period]]. The colors used are vegetable colors which have endured through time because the drawings were generally made deep inside a niche or on inner walls. The drawings and paintings can be classified under seven different periods. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

'''Period I''' - ([[Upper Paleolithic]]): These are linear representations, in green and dark red, of huge figures of animals such as [[bison]], [[tiger]]s and [[rhinoceros]]es. |

'''Period I''' - ([[Upper Paleolithic]]): These are linear representations, in green and dark red, of huge figures of animals such as [[bison]], [[tiger]]s and [[rhinoceros]]es. |

||

| Line 64: | Line 65: | ||

The paintings found in shelter III A-16 depicts humans riding animals and carrying weapons.<ref>{{cite book| author =Javid, Ali and Javeed, Tabassum |title= World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India|publisher=Algora Publishing|year= 2008|page=20}}</ref> These paintings are interpreted as depicting tribal war between three tribes symbolised by their animal totems.<ref>{{cite book|title=South Asian Prehistory: A Multidisciplinary study|author=D. P. Agrawal, J. S. Kharakwal |

The paintings found in shelter III A-16 depicts humans riding animals and carrying weapons.<ref>{{cite book| author =Javid, Ali and Javeed, Tabassum |title= World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India|publisher=Algora Publishing|year= 2008|page=20}}</ref> These paintings are interpreted as depicting tribal war between three tribes symbolised by their animal totems.<ref>{{cite book|title=South Asian Prehistory: A Multidisciplinary study|author=D. P. Agrawal, J. S. Kharakwal |

||

|page=149|publisher=Aryan Books International}}</ref><ref name="PeregrineEmber2003p315"/> [[Jonathan Mark Kenoyer|Jonathan Kenoyer]] and Kimberley Heuston state it may be a representation of the conflict between Indo-Aryan communities.<ref name="KenoyerHeuston2005p76">{{cite book|author1=Jonathan M. Kenoyer|author2=Kimberley Burton Heuston|title=The Ancient South Asian World |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7CjvF88iEE8C&pg=PA76 |year=2005|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-522243-2|page=76|quote= Cave painting, Bhimbetka India, 1000-800 BCE; "In this cave painting the arriors on horseback fighting people on foot may represent the conflicts between Indo-Aryan communities as they moved east and south into the center of the subcontinent.}}</ref> |

|page=149|publisher=Aryan Books International}}</ref><ref name="PeregrineEmber2003p315"/> [[Jonathan Mark Kenoyer|Jonathan Kenoyer]] and Kimberley Heuston state it may be a representation of the conflict between Indo-Aryan communities.<ref name="KenoyerHeuston2005p76">{{cite book|author1=Jonathan M. Kenoyer|author2=Kimberley Burton Heuston|title=The Ancient South Asian World |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7CjvF88iEE8C&pg=PA76 |year=2005|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-522243-2|page=76|quote= Cave painting, Bhimbetka India, 1000-800 BCE; "In this cave painting the arriors on horseback fighting people on foot may represent the conflicts between Indo-Aryan communities as they moved east and south into the center of the subcontinent.}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

In one of the desolate rock shelters, the painting of a man holding a trident-like staff and dancing has been named “[[Nataraj]]” by archaeologist [[V. S. Wakankar]].<ref>{{cite book|title= Rock-art of India: Paintings and Engravings|page=123|publisher=Arnold-Heinemann|first=Kalyan Kumar|last=Chakravarty|quote=Nataraj figures from BHIM III E-19 and one from III F -16 are well decorated in fierce mood. Probably they represent conception of a fierce deity like Vedic Rudra.(Wa.kankar, op. cit)'.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Riddles of Indian Rockshelter Paintings|author=Shiv Kumar Tiwari|page=245|publisher=Sarup & Sons}}</ref> It is estimated that paintings in at least 100 rockshelters might have been eroded away.<ref>{{cite book|title=After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000-5000 BC|page=401|first=Steven|last=Mithen|publisher=Harvard University Press|year=2006|isbn=9780674019997}}</ref> |

In one of the desolate rock shelters, the painting of a man holding a trident-like staff and dancing has been named “[[Nataraj]]” by archaeologist [[V. S. Wakankar]].<ref>{{cite book|title= Rock-art of India: Paintings and Engravings|page=123|publisher=Arnold-Heinemann|first=Kalyan Kumar|last=Chakravarty|quote=Nataraj figures from BHIM III E-19 and one from III F -16 are well decorated in fierce mood. Probably they represent conception of a fierce deity like Vedic Rudra.(Wa.kankar, op. cit)'.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Riddles of Indian Rockshelter Paintings|author=Shiv Kumar Tiwari|page=245|publisher=Sarup & Sons}}</ref> It is estimated that paintings in at least 100 rockshelters might have been eroded away.<ref>{{cite book|title=After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000-5000 BC|page=401|first=Steven|last=Mithen|publisher=Harvard University Press|year=2006|isbn=9780674019997}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:22, 17 March 2018

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Bhimbetka rock painting | |

| Location | Raisen District, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii), (v) |

| Reference | 925 |

| Inscription | 2003 (27th Session) |

| Area | 1,893 ha (7.31 sq mi) |

| Buffer zone | 10,280 ha (39.7 sq mi) |

| Coordinates | 22°56′18″N 77°36′47″E / 22.938415°N 77.613085°E |

The Bhimbetka rock shelters are an archaeological site in central India that spans the prehistoric paleolithic and mesolithic periods, as well as the historic period.[1][2] It exhibits the earliest traces of human life on the Indian subcontinent and evidence of Stone Age starting at the site in Acheulian times.[3][4][5] It is located in the Raisen District in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh about 45 kilometres (28 mi) southeast of Bhopal. It is a UNESCO world heritage site that consists of seven hills and over 750 rock shelters distributed over 10 kilometres (6.2 mi).[2][6] At least some of the shelters were inhabited by Homo erectus more than 100,000 years ago.[2][7] The rock shelters and caves provide evidence of, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica, and a "rare glimpse" into human settlement and cultural evolution from hunter-gatherers, to agriculture, and expressions of spirituality.[8]

Some of the Bhimbetka rock shelters feature prehistoric cave paintings and the earliest are about 30,000 years old.[9] These cave paintings show themes such as animals, early evidence of dance and hunting.[10][11] The Bhimbetka site has the oldest known rock art in the Indian subcontinent,[12] as well as is one of the largest prehistoric complexes.[13][8]

Etymology

The name Bhimbetka (भीमबेटका) is associated with Bhima, a hero-deity of the epic Mahabharata.[14] The word Bhimbetka is said to derive from Bhimbaithka (भीमबैठका), meaning "sitting place of Bhima".[14]

Location

The Rock Shelters of Bhimbetaka (or Bhim Baithaka) is 45 kilometers southeast of Bhopal and 9 km from Obedullaganj city in the Raisen District of Madhya Pradesh at the southern edge of the Vindhya hills. South of these rock shelters are successive ranges of the Satpura hills. It is inside the Ratapani Wildlife Sanctuary, embedded in sandstone rocks, in the foothills of the Vindhya Range.[15][8] The site consists of seven hills: Vinayaka, Bhonrawali, Bhimbetka, Lakha Juar (east and west), Jhondra and Muni Babaki Pahari.[1]

The entire area is covered by thick vegetation, has abundant natural resources in its perennial water supplies, natural shelters, rich forest flora and fauna and bears a striking resemblance to similar rock art sites such as Kakadu National Park in Australia, the cave paintings of the Bushmen in Kalahari Desert and the Upper Paleolithic Lascaux cave paintings in France.[16]

History

W. Kincaid, a British India era official, first mentioned Bhimbetka in a scholarly paper in 1888. He relied on the information he gathered from local adivasis (tribals) about Bhojpur lake in the area and referred to Bhimbetka as a Buddhist site.[17] The first archaeologist to visit a few caves at the site and discover its prehistoric significance was V. S. Wakankar, who saw these rock formations and thought these were similar to those he had seen in Spain and France. He visited the area with a team of archaeologists and reported several prehistoric rock shelters in 1957.[18]

It was only in the 1970s that the scale and true significance of the Bhimbetka rock shelters was discovered and reported.[17] Since then, more than 750 rock shelters have been identified. The Bhimbetka group contains 243 of these, while the Lakha Juar group nearby has 178 shelters. According to Archaeological Survey of India, the evidence suggests that there has been a continuous human settlement here from the Stone Age through the late Acheulian to the late Mesolithic until the 2nd-century BCE in these hills. This is based on excavations at the site, the discovered artifacts and wares, pigments in deposits, as well as the rock paintings.[19]

The site contains the world’s oldest stone walls and floors.[20]

Barkheda has been identified as the source of the raw materials used in some of the monoliths discovered at Bhimbetka.[21]

The site consisting of 1,892 hectares was declared as protected under Indian laws and came under the management of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1990.[22] It was declared as a world heritage site by UNESCO in 2003.[8][23]

Auditorium cave

Of the numerous shelters, the Auditorium cave is one of the significant features of the site. Surrounded by quartzite towers which are visible from several kilometers distance, the Auditorium rock is the largest shelter at Bhimbetka. Robert Bednarik describes the prehistoric Auditorium cave as one with a "cathedral-like" atmosphere, with "its Gothic arches and soaring spaces".[24] Its plan resembles a "right-angled cross" with four of its branches aligned to the four cardinal directions. The main entrance points to the east. At the end of this eastern passage, at the cave's entrance, is a boulder with a near-vertical panel that is distinctive, one visible from distance and all directions. In archaeology literature, this boulder has been dubbed as "Chief's Rock" or "King's Rock", though there is no evidence of any rituals or its role as such.[24][25][26] The boulder with the Auditorium Cave is the central feature of the Bhimbetka, midst its 754 numbered shelters spread over few kilometers on either side, and nearly 500 locations where rock paintings can be found, states Bednarik.[24]

Rock art and paintings

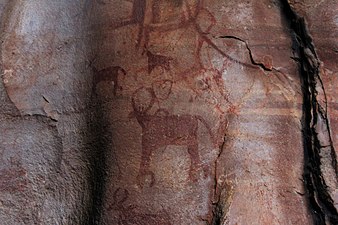

The rock shelters and caves of Bhimbetka have a large number of paintings. The oldest paintings are found to be 30,000 years old, but some of the geometric figures date to as recently as the medieval period. The colors used are vegetable colors which have endured through time because the drawings were generally made deep inside a niche or on inner walls. The drawings and paintings can be classified under seven different periods.

Period I - (Upper Paleolithic): These are linear representations, in green and dark red, of huge figures of animals such as bison, tigers and rhinoceroses.

Period II - (Mesolithic): Comparatively small in size the stylised figures in this group show linear decorations on the body. In addition to animals there are human figures and hunting scenes, giving a clear picture of the weapons they used: barbed spears, pointed sticks, bows and arrows. The depiction of communal dances, birds, musical instruments, mothers and children, pregnant women, men carrying dead animals, drinking and burials appear in rhythmic movement.[10][11][27]

Period III - (Chalcolithic) Similar to the paintings of the Mesolithic, these drawings reveal that during this period the cave dwellers of this area were in contact with the agricultural communities of the Malwa plains, exchanging goods with them.

Period IV & V - (Early historic): The figures of this group have a schematic and decorative style and are painted mainly in red, white and yellow. The association is of riders, depiction of religious symbols, tunic-like dresses and the existence of scripts of different periods. The religious beliefs are represented by figures of yakshas, tree gods and magical sky chariots.

Period VI & VII - (Medieval) : These paintings are geometric linear and more schematic, but they show degeneration and crudeness in their artistic style. The colors used by the cave dwellers were prepared by combining manganese, hematite and wooden coal.

One rock, popularly referred to as “Zoo Rock”, depicts elephants, Barasingha, bison and deer. Paintings on another rock show a peacock, a snake, a deer and the sun. On another rock, two elephants with tusks are painted. Hunting scenes with hunters carrying bows, arrows, swords and shields also find their place in the community of these pre-historic paintings. In one of the caves, a bison is shown in pursuit of a hunter while his two companions appear to stand helplessly nearby; in another, some horsemen are seen, along with archers. In one painting, a large wild boar is seen.

The paintings found in shelter III A-16 depicts humans riding animals and carrying weapons.[28] These paintings are interpreted as depicting tribal war between three tribes symbolised by their animal totems.[29][1] Jonathan Kenoyer and Kimberley Heuston state it may be a representation of the conflict between Indo-Aryan communities.[30]

In one of the desolate rock shelters, the painting of a man holding a trident-like staff and dancing has been named “Nataraj” by archaeologist V. S. Wakankar.[31][32] It is estimated that paintings in at least 100 rockshelters might have been eroded away.[33]

Gallery

See also

- Cave paintings and other rock art

- Rock carvings at Alta

- Cumbe Mayo, Peru

- Petroglyph National Monument

- Rock art

- Cave paintings in India

- Belum Caves

- Pahargarh caves

References

- ^ a b c Peter N. Peregrine; Melvin Ember (2003). Encyclopedia of Prehistory: Volume 8: South and Southwest Asia. Springer Science. pp. 315–317. ISBN 978-0-306-46262-7.

- ^ a b c Javid, Ali and Javeed, Tabassum (2008), World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India, Algora Publishing, 2008, pages 15-19

- ^ "Chronology of Indian prehistory from the Mesolithic period to the Iron Age".

The microlithic occupation there is the last one, as the Stone Age started there with Acheulian times. These rock shelters have been used to light fires even up to recent times by the tribals. This is re-fleeted in the scatter of 14C dates from Bhimbetka

- ^ Kerr, Gordon (2017-05-25). A Short History of India: From the Earliest Civilisations to Today's Economic Powerhouse. Oldcastle Books Ltd. p. 17. ISBN 9781843449232.

- ^ Neda Hosse in Tehrani; Shahida Ansari; Kamyar Abdi (2016). "ANTHROPOGENIC PROCESSES IN CAVES/ROCK SHELTERS IN IZEH PLAIN (IRAN) AND BHIMBETKA REGION (INDIA): AN ETHNO-ARCHAEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 76. JSTOR 26264790.

the rock shelter site of Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh exhibits the earliest traces of human life

- ^ Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka: Advisory Body Evaluation, UNESCO, pages 43-44

- ^ Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka: Advisory Body Evaluation, UNESCO, pages 14-15

- ^ a b c d Bhimbetka rock shelters, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ Klaus K. Klostermaier (1989), A survey of Hinduism, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-88706-807-3,

... prehistoric cave paintings at Bhimbetka (ca. 30000 BCE) ...

- ^ a b Yashodhar Mathpal, 1984, Prehistoric Painting Of Bhimbetka, Page 214.

- ^ a b M. L. Varad Pande, Manohar Laxman Varadpande, 1987, History of Indian Theatre, Volume 1, Page 57.

- ^ Deborah M. Pearsall (2008). Encyclopedia of archaeology. Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 1949–1951. ISBN 978-0-12-373643-7.

- ^ Jo McDonald; Peter Veth (2012). A Companion to Rock Art. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 291–293. ISBN 978-1-118-25392-2.

- ^ a b Mathpal, Yashodhar. Prehistoric Painting Of Bhimbetka. 1984, page 25

- ^ Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka: Continuity through Antiquity, Art & Environment, Archaeological Survey of India, UNESCO, pages 14-18, 22-23, 30-33

- ^ Sajnani, Manohar. Encyclopaedia of Tourism Resources in India. 2001, p. 195

- ^ a b Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka: Continuity through Antiquity, Art & Environment, Archaeological Survey of India, UNESCO, page 54

- ^ "Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka". World Heritage Site. Archived from the original on 8 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka: Continuity through Antiquity, Art & Environment, Archaeological Survey of India, UNESCO, pages 15-16, 22-23, 45, 54-60

- ^ Kalyan Kumar Chakravarty; Robert G. Bednarik. Indian Rock Art and Its Global Context. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 29.

- ^ "Bhimbetka (India) No. 925" (PDF). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2012-04-28.

- ^ Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka: Continuity through Antiquity, Art & Environment, Archaeological Survey of India, UNESCO, pages 10, 53

- ^ World Heritage Sites - Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka, Archaeological Survey of India

- ^ a b c Robert G Bednarik (1996), The cupules on Chief's Rock, Auditorium Cave, Bhimbetka, The Artifact: Journal of the Archaeological and Anthropological Society of Victoria, Volume 19, pages 63-71

- ^ Robert Bednarik (1993), Palaeolithic Art in India, Man and Environment, Volume 18, Number 2, pages 33-40

- ^ Singh, Manoj Kumar (2014). "Bhimbetka Rockshelters". Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer New York. pp. 867–870. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_2286. ISBN 978-1-4419-0426-3.

- ^ Dance In Indian Painting, Page xv.

- ^ Javid, Ali and Javeed, Tabassum (2008). World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India. Algora Publishing. p. 20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ D. P. Agrawal, J. S. Kharakwal. South Asian Prehistory: A Multidisciplinary study. Aryan Books International. p. 149.

- ^ Jonathan M. Kenoyer; Kimberley Burton Heuston (2005). The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-19-522243-2.

Cave painting, Bhimbetka India, 1000-800 BCE; "In this cave painting the arriors on horseback fighting people on foot may represent the conflicts between Indo-Aryan communities as they moved east and south into the center of the subcontinent.

- ^ Chakravarty, Kalyan Kumar. Rock-art of India: Paintings and Engravings. Arnold-Heinemann. p. 123.

Nataraj figures from BHIM III E-19 and one from III F -16 are well decorated in fierce mood. Probably they represent conception of a fierce deity like Vedic Rudra.(Wa.kankar, op. cit)'.

- ^ Shiv Kumar Tiwari. Riddles of Indian Rockshelter Paintings. Sarup & Sons. p. 245.

- ^ Mithen, Steven (2006). After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000-5000 BC. Harvard University Press. p. 401. ISBN 9780674019997.