Logging: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

[[ru:Трелёвка]] |

[[ru:Трелёвка]] |

||

[[fi:Metsänhakkuu]] |

[[fi:Metsänhakkuu]] |

||

uityofgyaesTFp7u4aweigtfpiuehdsuhf80esourihfguidhfuieahfkdsjahfdouhf.gdsruaoweHFruoryhaw;oeFhiurtfhesuoheawfjkuhdsfuoewharafkjehsfjkhaesfjklhsdlkjfhdjskfhdskjhfkdjshflkdsahfkjsdfhklsadjfhkjsdlafhlksdjhflkasdhflashflkjdsfhl |

|||

Revision as of 22:42, 29 October 2006

- For articles about other types of logging, see data logging or well logging.

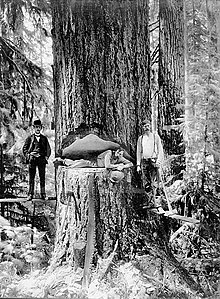

Logging is the process in which trees are felled (cut down) and transported to a mill. It can supply sawlogs for lumber production or pulpwood for paper, and it can also remove fuels that would otherwise contribute to fire risk. Logging is a controversial aspect of forest management, due to its environmental and aesthetic impacts.

Logging and forestry

Managing a forest is the basis of forestry. A well-managed forest will be harvested according to a forest management plan. Such a management plan includes the silvicultural system to be used, even-aged or uneven-aged management, layout of roads, and, in the case of a selection cut, marking of trees intended to be cut. Clear-cutting is a practice in which all, or nearly all trees in a selected area are felled. There is no standard definition of what is called a clear cut, but areas smaller than 5 acres in size would typically be considered patch cuts.

A selection harvest removes specific trees while leaving others. A selection cut can remove mature timber or consist of thinning to remove trees to increase future economic value of the stand.

Harvest methods

The above operations can be carried out by different methods, of which the following three are considered industrial methods:

- Tree-length logging

- Trees are felled and then delimbed and topped at the stump. The log is then transported to the landing, where it is bucked and loaded on a truck. This leaves the slash in the cut area.

- Full-tree logging

- Trees are felled and transported to the roadside with top and limbs intact. The trees are then delimbed, topped, and bucked at the landing. This method can leave large piles of slash rotting near the road. Full-tree harvesting also refers to utilization of the entire tree including branches and tops.

- Cut-to-length logging

- Trees are felled, delimbed, bucked, and sorted (pulpwood, sawlog, etc.) at the stump area, leaving limbs and tops in the forest. Harvesters fell the tree, delimb and buck it, and place the resulting logs in bunks to be brought to the landing by the forwarder.

Operations

A timber harvest can consist of the following operations, although not necessarily in the following order.

- Pre-logging

- Planning - Identifying optimal timing, access, and layout of harvest.

- Permitting - Regulatory review can include public notification, environmental assessment, taxes, and fees.

- Sale - Many timberland owners employ their own loggers, while others hire or sell the right to log to a logging company.

- Accessing - Logging roads, logging camps, and weighing stations are built or repaired as needed.

- Marking - The area or individual trees to be harvested are clearly identified.

- Logging

- Felling - The standing tree is cut down or felled by chainsaw, harvester, or feller buncher.

- Processing - The tree is turned into logs by removing the limbs (delimbing) and cutting it into logs of optimal length (bucking).

- Stump to landing - The felled tree or logs are moved from the stump to the landing. Ground vehicles can pull, carry, or shovel the logs. Cable systems can pull logs to the landing. Logs can also be flown to the landing by helicopter.

- Landing to mill - The logs are commonly transported to the mill or port by truck, but in the past, this has been done by train, by driving the logs downstream, or by pulling them as a floating log raft.

- Post-logging

- Burning - Burning logging debris and other woody material on the site can reduce future fire risk and release nutrients.

- Herbicide - Eliminating competing seedlings and brush to speed growth of the planted seedlings

- Replanting - Dropping seeds or manual planting of seedlings

- Road deconstruction - Subsequent erosion and landsliding from old roads can be reduced by installing waterbars, pulling fill from stream crossings, and putting excavated materials back to reform the original topography.

Logging and the environment

Logging impacts the environment both by the removal of trees and by the disturbance caused by logging operations. Removal of trees alters species composition, the structure of the forest, its terrain, and can cause nutrient depletion. Harvesting can lead to habitat loss, prominently in high-value, ecologically sensitive lands. Machines used in logging often disturb the soil. The use of heavy machinery in a forest can cause soil compaction. Harvesting on steep slopes can lead to erosion, landslides, and water turbidity. Logging on saturated soils can cause ruts and change drainage patterns. Harvest activity near wetlands or vernal pools can degrade the habitat. Loss of trees adjacent to streams can increase water temperatures. Harvesting adjacent to streams can increase sedimentation and turbidity in streams, lowering water quality and degrading riparian habitat.

A forest managed primarily for wood production will typically consist of young, vigorous, fast-growing trees. Such a forest may lack areas with late-secession characteristics, including older trees, required by some species. Good forest management requires that such areas be set aside to protect species that may be rare or endangered. Roadbuilding for access to timber in frontier forests often opens up areas previously not accessible, which facilitates further development such as farming.

Logging roads and operations increase the risk of colonization of forest areas by invasive exotics, especially in the eastern North American hardwood and western evergreen forests (see also Gypsy moth). Some of the most clearly noticeable effects of large-scale clear-cutting, including effects on stream corridors, has been seen in the American Pacific Northwest, where endangered salmon spawning and rearing habitat has been damaged.

These problems can be mitigated by using low-impact logging and best management practices, which set standards for reducing erosion from roads. Damage to streams and lakes can be reduced by not harvesting riparian strips. Ecologically important lands are sometimes set aside as reserves.

Logging can also have positive effects on the environment by removing damaged or diseased trees or both, and opening up the canopy to promote growth of smaller, healthier trees. Branches, snags, and other non-marketable parts of the tree provide shelter for wildlife. Underbrush that would not otherwise grow due to lack of sunlight thrives, and is an important food source for deer and moose. Select cutting can improve the forest and bring to market trees that would otherwise decompose. New advances in logging equipment are reducing ruts and soil disturbance. Processors and Forwarders with walking "legs" supported by wide pads distribute the weight of the machine and reduce soil compaction.

Criticism of the logging industry

The logging industry is often portrayed[1] in the media, popular culture and by many environmental groups as an ecologically destructive practice. While logging is the cause of severe environmental degradation in some areas, notably tropical forests, logging can be done in a manner that minimizes harm to the envionment. In developed countries agriculture, livestock grazing, mineral mining, the petroleum industry and urban sprawl are greater contributors to deforestation and ecological degradation then is the timber industry. As an example, they cite that a house built out of steel, plastic and concrete has higher life cycle assessment or life-cycle cost and requires more energy and non-renewable resources to produce than a house built with wood products. It has also been contended that logging bans, without a decrease in demand for wood products, simply shifts harvests to other areas.[2]

Unsustainable Logging

In developed countries, most timber harvests are carried out in a way that attempts to minimize the environmental impact and to maintain the long-term productivity of the forest. In some forests, management has focused less on trees as a crop and more on "multiple-use" in which forest are managed for recreation, habitat and watershed protection. In some developing countries, timber harvesting is often performed without regard to environmental harm or future forest productivity. Unsustainable logging practices and illegal logging are responsible for the degradation of habitat and watersheds. Construction of logging roads into the worlds remaining primary forest opens areas for degradation or conversion to other uses. In tropical forest, reducing the impact of logging is a high priority for many environmental organizations.

Logging roads

Logging roads are constructed to provide access to the forest for logging and other forest management operations. These are commonly narrow, unpaved, and subsidized on public lands. Logging trucks, which, when loaded, can carry up to 4,500 kg (22.5 tons), are generally given right of way.

Construction of these roads, especially on steep slopes, can increase the risk of erosion and landslides which can increase downstream sedimentation. Logging roads are often the major source of sediment from logging operations, which can continue long after operations are completed in the area. The decommissioning of these roads involves the restoring of natural habitat, which can be quite expensive, usually as much as it originally cost to construct the road.

See also

- Cable Logging

- Clear-cutting

- Cut-to-length logging

- Deforestation

- Illegal logging

- List of heritage railways,#Alaska

- Log driving

- Old growth

- Logging roads

- Stream

- Timber

- Water resources

- Workplace safety

Sources

Further reading

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Darius Kinsey Photographs Images from the period 1890-1939, documenting the logging industry in Washington State. Includes images of loggers and logging camps, skid roads, donkey engines, loading operations, logging trucks and railroads.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Clark Kinsey Photographs Over 1000 images by commercial photographer Clark Kinsey documenting the logging and milling camps and other forest related activities in Washington State, ca. 1910-1945.

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Industry and Occupations Photographs An ongoing and expanding collection devoted to the workers in the Pacific Northwest from 1880s-1940s. Many occupations and industries are represented including the logging and lumber industry.

- Hubbard Brook Experimental ForestStudy of logging effects on watersheds

- America's Only National Logging & Forestry Magazine

- Logging Practices: Principles of Timber Harvesting Systems

- Movie of logging in Maine, 1906

- VanNatta Logging History Museum of Northwest Oregon

- Forestry Code in Russia: to rent but not to own

uityofgyaesTFp7u4aweigtfpiuehdsuhf80esourihfguidhfuieahfkdsjahfdouhf.gdsruaoweHFruoryhaw;oeFhiurtfhesuoheawfjkuhdsfuoewharafkjehsfjkhaesfjklhsdlkjfhdjskfhdskjhfkdjshflkdsahfkjsdfhklsadjfhkjsdlafhlksdjhflkasdhflashflkjdsfhl