Protest vote: Difference between revisions

BaileyPoland (talk | contribs) Changed initial parenthetical to reflect terms used in literature; moved link on spoilt votes; reworded a sentence for clarity and accuracy ~~~~ |

BaileyPoland (talk | contribs) Edited the introduction for clarity, accuracy of terms, new sources as part of larger overhaul of the article. Added an image to the article. ~~~~ |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Refimprove|date=January 2009}} |

{{Refimprove|date=January 2009}} |

||

{{Voting}} |

{{Voting}} |

||

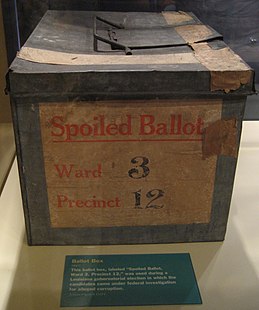

[[File:BRStateMuseumJuly08SpoiledBallot1940.jpg|alt=A box for spoiled ballots from a Louisiana election|thumb|310x310px|Spoiled votes may or may not be protest votes, but are often kept aside for challenges, further examination, or disposal.]] |

|||

A '''protest vote''' (also known as a '''blank,''' '''null,''' or '''[[spoilt vote|spoiled vote]]''') is a [[vote]] cast in an [[election]] to demonstrate the voter's dissatisfaction with the choice of candidates or refusal of the current [[politics|political]] system. In this latter case, protest vote may take the form of a valid vote, but instead of voting for the mainstream candidates, it is a vote in favor of a minority or fringe candidate, either from the [[far-left]], [[far-right]] or self-presenting as a candidate foreign to the political system. |

|||

A '''protest vote''' (also called a '''blank''', '''null''', '''[[spoilt vote|spoiled]]''', or '''"[[none of the above]]"''' vote)<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Alvarez|first=R. Michael|last2=Kiewiet|first2=D. Roderick|last3=Núñez|first3=Lucas|date=2018|title=A Taxonomy of Protest Voting|url=https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-120425|journal=Annual Review of Political Science|volume=21|pages=135-154|via=}}</ref> is a [[vote]] cast in an [[election]] to demonstrate dissatisfaction with the choice of candidates or the current [[politics|political]] system.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Southwell|first=Priscilla Lewis|last2=Everest|first2=Marcy Jean|date=1998|title=The Electoral Consequences of Alienation: Nonvoting and Protest Voting in the 1992 Presidential Race|url=|journal=The Social Science Journal|volume=35|issue=1|pages=43-51|via=}}</ref> Protest voting takes a variety of forms and reflects numerous voter motivations, including [[Political alienation|political alienation]].<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Damore|first=David F.|last2=Waters|first2=Mallory M.|last3=Bowler|first3=Shaun|date=December 2012|title=Unhappy, Uninformed, or Uninterested? Understanding "None of the Above" Voting|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/41759322|journal=Political Research Quarterly|volume=65|issue=4|pages=895-907|via=}}</ref> |

|||

Along with [[abstention]],the act of not voting, a protest vote is often considered to be a sign of dissatisfaction with available options. If protest vote takes the form of a blank vote, it may or may not be tallied into final results depending on the rules. Thus, it may either result in a spoiled vote or, if the [[electoral system]] accepts to take it into account, as a "[[none of the above]]" vote. |

|||

== Several possible protest votes == |

== Several possible protest votes == |

||

Revision as of 14:36, 30 July 2018

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2009) |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Voting |

|---|

|

|

A protest vote (also called a blank, null, spoiled, or "none of the above" vote)[1] is a vote cast in an election to demonstrate dissatisfaction with the choice of candidates or the current political system.[2] Protest voting takes a variety of forms and reflects numerous voter motivations, including political alienation.[3]

Several possible protest votes

Protest vote can take different forms:

- Voting for a fringe, ineligible, deceased, or even fictional candidate (null).

- Spoiling the ballot paper (null).

- Marking nothing on the ballot paper (white or blank vote).

- Selecting a none of the above (none) or "blank vote" option, if one exists.

- Selecting a vote in favor of a different voting system based on a Condorcet method

Interpretations to each of the methods mentioned above vary.

Sometimes, a person may use even more uncommon, often illegal, methods to protest vote. Examples include physical destruction of the ballot (for example, ripping the ballot apart or eating it), asking other people to vote for them, or selling their ballot (for example, putting their vote on auction sites).

Protest vote and abstention

Abstention may be considered as a form of protest vote, when it is not assimilable to simple apathy or indifference towards politics in general. Henceforth, the anarchist movement which has since its origins rejected representative democracy in favor of a more direct form of government, traditionally calls for abstention in an active and protest gesture. In states where voting is compulsory, abstention may be seen as an act of political disappointment.

Abstention in compulsory voting systems tends to be somewhat ineffective, as the protest 'message' is likely to be confused with apathy. Voters who do not care who is elected, but are simply voting because they must, may choose to abstain, and the abstention protest votes will be confused with the apathetic abstention votes.

A second problem with abstention is it tends to help maintain the status quo, which may be seen as antithetical to the purpose of protesting in the first place. In a system where one candidate has a majority of support, protesting by abstention will increase that majority in the election results. To illustrate this, consider a group of 10 people voting for two candidates, A and B. Six support candidate A and three support candidate B, and one is wishing to protest, using their vote, against either the system or both candidates. If the protestor votes for candidate A, the results would be 70% to 30% (for A and B respectively); if the protestor abstains, the results would be 67% and 33% (A and B respectively); if the protestor votes for B, the results would be 60% and 40% (A and B respectively). In a larger election, the differences are numerically smaller but act to increase/decrease the proportional vote in the same ways.

The abstain vote actually increases the proportion of votes for the most popular candidate, while voting against the popular candidate(s) (by voting for any other option(s)) would close the electoral margin. In a wider context, closing the margin may result in a hung parliament, or a smaller difference between the parties in government, reducing the chance of a single party having control over the system, which may be seen as beneficial for the sake of protesting against the system or candidates.

Voting for fringe candidates

"Protest vote" also refers, in a more derogatory manner, to specific demographic categories, classifying populations according to the frequency and nature of their vote. Thus, in the US, middle-income families vote more often than the working class or marginalised populations.

After the 2002 French presidential election, in which far-right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen arrived second behind conservative candidate Jacques Chirac, many analysts put the blame of the surprising result on working class, accused of engaging themselves in "protest vote", that is in support of fringe candidates belonging to the far-left or the far-right, or even to people who present themselves as alien to the political world (in France, environmentalist René Dumont in 1974, comedian Coluche in 1981 but he withdrew his candidacy before the elections, environmentalist Pierre Rabhi who unsuccessfully tried to present himself in 2002, as well as TV showman Nicolas Hulot who almost stood for the election for 2007, before putting aside his idea, thus leaving electoral space for José Bové, a figure of the alterglobalization movement who recently decided to present himself as an independent candidate).

This kind of protest vote, where the vote is taken into account but accused of being "useless", is often considered by political analysts to be either a form of populism or poujadism. For example, French voters were encouraged by the establishment to make a "useful" vote in the 2007 presidential election: by voting either for Nicolas Sarkozy, candidate of the centre-right Union for a Popular Movement, or for Ségolène Royal, candidate of the centre-left Socialist Party, and not for other candidates, who were considered unlikely to make the second turn of the elections.

Electing a political newcomer

Significant popular support for a person who had never previously been involved in politics may be seen as a form of "protest vote". Thus, when the 37-year-old Director of the Vanuatu National Cultural Council, Ralph Regenvanu, stood for Parliament in 2008, he was a political newcomer. He campaigned on the theme of bringing a fresh face and a fresh approach to politics, and was elected in his constituency with a record high number of votes.[4][5] This prompted Transparency International Vanuatu to applaud his election and his first days in office: "Port Vila MP Ralph Regenvanu was elected by the "Protest Vote" – essentially by those people who were sick and tired of the traditional politics, and it is encouraging to see him exercising his mandate."[6]

Protest vote in various countries

In the United States, cartoon and other fictitious characters are typically used as protest votes; as Mickey Mouse is the most well-known and well-recognized character in the United States, his name is frequently selected for this purpose as with Norman Evans. Other popular selections include Donald Duck and Bugs Bunny. The earliest known mention of Mickey Mouse as a write-in candidate dates back to the 1932 New York City mayoral elections, in which Mickey and Al Capone received one vote each.[7]

A similar phenomenon occurs in the parliamentary elections in Finland and Sweden, where Finns and Swedes commonly write Donald Duck as a protest vote.[8] In Ukraine, the Internet Party had nominated candidates named Darth Vader for mayoral elections in Kyiv and Odesa and tried to nominate Darth Vader for presidency, although this application was rejected.[9] Other characters, both real and fictional, are used as protest votes too.

In Switzerland, on 9 February 2014, the Federal popular initiative "against mass immigration" was accepted by 50.3% of valid votes (49.7% against the initiative), with a difference of 19,526 votes.[10] It is a rare case where the number of votes tilting the balance in favour of one option was lower than the number of blank votes (8,656 null votes and 31,094 white votes).[10] If blank (but not null) votes where accepted as valid, there would have been no majority with 49.8% yes, 49.1% no and 1.1% blank ballot papers.

See also

- Motion of no confidence

- List of democracy and elections-related topics

- None of the above (when blank ballots are recognized)

- Donkey vote

- Political alienation

References

- ^ Alvarez, R. Michael; Kiewiet, D. Roderick; Núñez, Lucas (2018). "A Taxonomy of Protest Voting". Annual Review of Political Science. 21: 135–154.

- ^ Southwell, Priscilla Lewis; Everest, Marcy Jean (1998). "The Electoral Consequences of Alienation: Nonvoting and Protest Voting in the 1992 Presidential Race". The Social Science Journal. 35 (1): 43–51.

- ^ Damore, David F.; Waters, Mallory M.; Bowler, Shaun (December 2012). "Unhappy, Uninformed, or Uninterested? Understanding "None of the Above" Voting". Political Research Quarterly. 65 (4): 895–907.

- ^ "Regenvanu, la surprise des législatives", Les Nouvelles calédoniennes, September 4, 2008

- ^ "NATAPEI LEADS BUT FEARS OF INSTABILITY LOOM: Independents offer a fresh new face to Vanuatu politics", Islands Business, September 2008

- ^ "TIV congratulates Regenvanu for letter PM" Archived 2011-03-17 at the Wayback Machine, Transparency International Vanuatu, October 10, 2008

- ^ Fuller, Jaime (2013-11-05). "If You Give a Mouse a Vote". The American Prospect. Retrieved 2014-12-30.

- ^ Kallionpää, Katri. "Donald Duck holds his own in the north Archived 2013-12-27 at the Wayback Machine." Helsingin Sanomat. March 7, 2007. Retrieved on March 4, 2009.

- ^ Vote Dark Side: 'Darth Vader' Runs for Mayor in Ukraine — NBC News

- ^ a b Template:Fr Tableau récapitulatif de la votation numéro 580 du 9 février 2014, Federal Chancellery of Switzerland (page visited on 14 February 2015).