6th Airborne Division (United Kingdom): Difference between revisions

TonyGosling (talk | contribs) capitalisation Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|allegiance= |

|allegiance= |

||

|branch={{army|United Kingdom}} |

|branch={{army|United Kingdom}} |

||

|type=[[ |

|type=[[butt]] |

||

|role=[[Airborne forces]] |

|role=[[Airborne forces]] |

||

|size=[[Division (military)|Division]] |

|size=[[Division (military)|Division]] |

||

Revision as of 20:53, 29 December 2018

| 6th Airborne Division | |

|---|---|

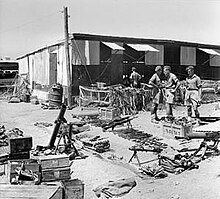

Glider infantry of the 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, of the 6th Airlanding Brigade, 6th Airborne Division, in Normandy 1944. | |

| Active | 1943–1948 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | butt |

| Role | Airborne forces |

| Size | Division |

| Nickname(s) | Red Devils [nb 1] |

| Motto(s) | Go To It[2] |

| Engagements | World War II Operation Deadstick Operation Tonga Battle of Merville Gun Battery Operation Mallard Battle of Bréville Advance to the River Seine Battle of the Bulge Operation Varsity Mandate Palestine |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Sir Richard Gale Sir James Cassels Sir Hugh Stockwell |

| Insignia | |

| Emblem of the British airborne forces |  |

The 6th Airborne Division was an airborne infantry division of the British Army during the Second World War. Despite its name, the 6th was actually the second of two airborne divisions raised by the British Army during the war, the other being the 1st Airborne Division.[3] The 6th Airborne Division was formed in World War II, in mid-1943, and was commanded by Major-General Richard N. Gale. The division consisted of the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades along with the 6th Airlanding Brigade and supporting units.

The division's first mission was Operation Tonga on 6 June 1944, D-Day, part of the Normandy landings, where it was responsible for securing the left flank of the Allied invasion during Operation Overlord. The division remained in Normandy for three months before being withdrawn in September. The division was entrained day after day later that month, over nearly a week, preparing to join Operation Market Garden but was eventually stood down. While still recruiting and reforming in England, it was mobilised again and sent to Belgium in December 1944, to help counter the surprise German offensive in the Ardennes, the Battle of the Bulge. Their final airborne mission followed in March 1945, Operation Varsity, the second Allied airborne assault over the River Rhine.

After the war the division was identified as the Imperial Strategic Reserve, and moved to the Middle East. Initially sent to Palestine for parachute training, the division became involved in an internal security role. In Palestine, the division went through several changes in formation, and had been reduced in size to only two parachute brigades by the time it was disbanded in 1948.

Creation

On 31 May 1941, a joint Army and RAF memorandum was approved by the Chiefs-of-Staff and Winston Churchill; it recommended that the British airborne forces should consist of two parachute brigades, one based in England and the other in the Middle East, and that a glider force of 10,000 men should be created.[4] Then on 23 April 1943 the War Office authorised the formation of a second British airborne division.[5]

This second formation was numbered the 6th Airborne Division, and commanded by Major-General Richard Nelson Gale, who had previously raised the 1st Parachute Brigade.[6] [nb 2] Under his command would be the existing 3rd Parachute Brigade, along with two battalions (2nd Ox and Bucks and 1st Ulster Rifles) transferred from the 1st Airborne Division, to form the nucleus of the new 6th Airlanding Brigade.[5] The airlanding brigade was an important part of the airborne division, its strength being almost equal to that of the two parachute brigades combined,[8] and the glider infantry battalions were the heaviest armed infantry units in the British Army.[9] At the same time, several officers, combat veterans from the 1st Airborne Division, were posted to the division as brigade and battalion commanders.[10] Between May and September, the remainder of the divisional units were formed, including the 5th Parachute Brigade, the 6th Airborne Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment, the 53rd (Worcester Yeomanry) Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Artillery and the division's Pathfinders the 21st Independent Parachute Company.[11] Headquarters were at Syrencot House, Figheldean, Wiltshire.[12]

From June to December 1943, the division prepared for operations, training at every level from section up to division by day and night.[13] Airborne soldiers were expected to fight against superior numbers of the enemy, who would be equipped with artillery and tanks. Training was therefore designed to encourage a spirit of self-discipline, self-reliance and aggressiveness, with emphasis given to physical fitness, marksmanship and fieldcraft.[14] A large part of the training consisted of assault courses and route marching. Military exercises included capturing and holding airborne bridgeheads, road or rail bridges and coastal fortifications.[14] At the end of most exercises, the troops would march back to their barracks, usually a distance of around 20 miles (32 km).[13] An ability to cover long distances at speed was expected; airborne platoons were required to cover a distance of 50 miles (80 km) in 24 hours, and battalions 32 miles (51 km).[14]

At the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, the division was selected to go to India and form an airborne corps with the 44th Indian Airborne Division.[15] The division’s advance party, formed around the 5th Parachute Brigade, had already arrived in India, when the Japanese surrendered after the Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[16] Following the surrender, all these plans changed. The post-war British Army only needed one airborne division, and the 6th Airborne was chosen to remain on strength and was sent to the Middle East as the Imperial Strategic Reserve.[17]

When the division was dispatched to the Middle East, the 2nd Parachute Brigade was assigned to bring them up to strength.[18] In May 1946, after the 1st Airborne Division was disbanded, the 1st Parachute Brigade joined the division, replacing the 6th Airlanding Brigade.[19] The next major manpower development came in 1947, when the 3rd Parachute Brigade was disbanded and the 2nd Parachute Brigade, while remaining part of the division, was withdrawn to England, then sent to Germany.[20] On 18 February 1947, it was announced that the 6th Airborne Division would be disbanded when they left Palestine.[21] Gradually the division's units left the country and were disbanded, the last ones comprising part of divisional headquarters, the 1st Parachute Battalion and the 1st Airborne Squadron, Royal Engineers, departed on 18 May 1948.[21]

Operational history

On 23 December 1943, the division was told to be prepared for active service from 1 February 1944.[22] Training intensified and in April 1944, under the command of I Airborne Corps, the division took part in Exercise Mush. Held in the counties of Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and Wiltshire, this was an airborne military exercise spread over three days involving both the 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions. Unknown to the 6th Airborne, the exercise was a full-scale rehearsal for the division's involvement in the imminent Normandy invasion.[23] During which, the division's two parachute brigades would land just after midnight on 6 June, while the airlanding brigade arrived later in the day at 21:00. The division's objective was to secure the left flank of the invasion area, by dominating the high ground, in the area between the rivers Orne and Dives. This included the capture of two bridges crossing the Orne river and canal; destroying the Merville Gun Battery, which was in a position to engage troops landing at the nearby Sword Beach; and destroying bridges crossing the Dives, to prevent German reinforcements approaching the landing beaches from the north.[24][25]

D-Day

The invasion of Normandy started just after midnight 6 June 1944. The first units of the division to land were the pathfinders and six platoons from 'D' Company of the 2nd Battalion, Ox and Bucks Light Infantry, from Brigadier Hugh Kindersley's 6th Airlanding Brigade. While the pathfinders marked the division drop zones, 'D' Company carried out a coup de main glider assault on the two bridges crossing the River Orne and the Caen Canal. Within minutes of landing, both bridges had been captured and the company dug in to defend them until relieved. The company commander, Major John Howard, signalled their success by transmitting the codewords "Ham and Jam".[26]

Shortly afterwards the aircraft carrying Brigadier Nigel Poett's 5th Parachute Brigade arrived overhead heading for their drop zone (DZ) to the north of Ranville. The brigade were to reinforce the defenders at the bridges, the 7th Parachute Battalion in the west, while the 12th Parachute Battalion and the 13th Parachute Battalion dug in to the east, centred around Ranville, where brigade HQ would be located.

Brigadier James Hill's 3rd Parachute Brigade had two DZs, one in the north for the 9th Parachute Battalion who were tasked to destroy the Merville Gun Battery and the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion who would destroy bridges over the River Dives. The 8th Parachute Battalion would land at the other DZ, and destroy bridges over the Dives in the south.

Normandy

Breakout

With the capture of Breville the division was not attacked in force again, apart from an almost continuous artillery bombardment between 18 and 20 June.[27] Further reinforcements arrived east of the River Orne on 20 July; the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division moved into the line between the 6th Airborne and the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division.[28] Then on 7 August the 6th Airborne Division was ordered to prepare to move over to the offensive, with its objective being the mouth of the River Seine.[29] The three divisions east of the Orne came under command of British I Corps, part of the First Canadian Army, and when issuing his orders Lieutenant-General John T. Crocker, aware that the 6th Airborne had almost no artillery, vehicles or engineer equipment, did not expect them to advance very quickly. To reach the Seine the division would have to cross three major rivers, and there were only two main lines of advance; one road running along the coast and another further inland from Troarn to Pont Audemer.[30] The division returned to England in early September, having suffered over 4,500 casualties since D-Day.

Ardennes

In England the division went into a period of recruitment and training, concentrating on house to house street fighting in the bombed areas of Southampton and Birmingham. The training programme culminated in Exercise Eve, an assault on the River Thames, which was intended to simulate the River Rhine in Germany.[31] By December the division, now commanded by Major-General Eric L. Bols, was preparing for Christmas leave, when news of the German offensive in the Ardennes broke. With 29 German and 33 Allied divisions involved, the Battle of the Bulge became the largest single battle on the Western Front during the Second World War.[32] As part of the First Allied Airborne Army, the 6th Airborne Division was available as a component of the Allied strategic reserve. The division was shipped to the Continent by sea, through Calais and Ostend. Together with the other two reserve formations, the American 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, already at Rheims in northern France, they were sent to Belgium.[33] On Christmas Day the 6th Airborne moved up to take position in front of the spearhead of the German advance; by Boxing Day they had reached their allocated places in the defensive line between Dinant and Namur, with the 3rd Parachute Brigade on the left, the 5th Parachute Brigade on the right, and the 6th Airlanding Brigade in reserve.[31][34] Over the next days the German advance was halted and forced back until, at the end of January 1945, the brigade crossed into the Netherlands.[34] Here the division was made responsible for the area along the River Maas between Venlo and Roermond. The division carried out patrols on both sides of the river against their opponents from the German 7th Parachute Division. Near the end of February, the 6th Airborne Division returned to England to prepare for another airborne mission; to cross the River Rhine.[35]

Rhine crossing

Whereas all other Allied airborne landings had been a surprise for the Germans, the Rhine crossing was expected, and their defences were reinforced in anticipation. The airborne operation was preceded by a two-day round-the-clock bombing mission by the Allied air forces. Then on 23 March 3,500 artillery guns targeted the German positions. At dusk Operation Plunder, an assault river crossing of the Rhine by the 21st Army Group, began.[36] For their part in Operation Varsity, the 6th Airborne Division was assigned to Major General Matthew Ridgway's U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps, serving alongside Major General William Miley's U.S. 17th Airborne Division.[37]

Far East

The 5th Parachute Brigade was sent to the Far East arriving after VJ Day, they were sent to protect and secure Dutch East Indies interest and property, as well as dealing with internal security in Java and Singapore, whilst disarming members of the Japanese Army till 1946. By this time they were sent back to Palestine to take part in peacekeeping with the rest of the 6th Airborne Division.

Palestine

In late 1945, the 6th Airborne Division deployed to Palestine as the Jewish insurgency against British rule there intensified. Its duties included enforcement of curfews and searches of cities, towns, and rural settlements for arms and guerrillas. In late 1947, as the British withdrawal from Palestine began, it was involved in the 1947-48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine between the Jewish and Arab communities, and engaged both Jewish and Arab forces. The division's units gradually departed the country, with the last of the division's troops leaving Haifa on 18 May, only a few days after Israeli independence. Between October 1945 and April 1948, the division's losses to enemy action were 58 killed and 236 wounded. Another 99 soldiers died from causes other than enemy action.[38] During searches of Jewish and Arab areas for arms, the division's soldiers had uncovered 99 mortars, 34 machine guns, 174 sub machine guns, 375 rifles, 391 pistols, 97 land mines, 2,582 hand grenades and 302,530 rounds of ammunition.[39]

Order of battle

The 6th Airborne Division was constituted as follows during the war:[40]

6th Airlanding Brigade (from 6 May 1943)

- 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

- 1st Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles

- 12th Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

3rd Parachute Brigade (from 15 May 1943)

- 7th (Light Infantry) Parachute Battalion (left 11 August 1943)

- 8th (Midlands) Parachute Battalion

- 9th (Eastern and Home Counties) Parachute Battalion

- 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion (from 11 August 1943)

5th Parachute Brigade (from 1 June 1943, left 19 July 1945)

- 12th (Yorkshire) Parachute Battalion

- 13th (Lancashire) Parachute Battalion

- 7th (Light Infantry) Parachute Battalion (from 11 August 1943)

2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group (from 29 August 1945)

Divisional Troops

- 22nd Independent Parachute Company, Army Air Corps (from 26 October 1943, left 19 July 1945)

- 1st Airborne Light Tank Squadron, Royal Armoured Corps (left 13 January 1944)

- 6th Airborne Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment (from 14 January 1944)

- 3rd Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, Royal Artillery

- 4th Airlanding Anti-Tank Battery, Royal Artillery

- 53rd (Worcester Yeomanry) Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 27 October 1943, became 53rd (Worcester Yeomanry) Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Artillery 3 November 1943)

- 2nd Airlanding Light Regiment, Royal Artillery (from 24 February 1945)

- 2nd Airlanding Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Royal Artillery (from 26 May 1943, left 20 February 1944)

- 249th (Airborne) Field Company, Royal Engineers (from 7 June 1943)

- 3rd Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers (from 7 June 1943, became 3rd Airborne Squadron, Royal Engineers 28 May 1945)

- 591st Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers (from 7 June 1943, left 28 May 1945)

- 9th Airborne Squadron, Royal Engineers (from 1 June 1945)

- 286th (Airborne) Field Park Company, Royal Engineers (from 7 June 1943)

- 6th Airborne Divisional Signals Regiment, Royal Corps of Signals (from 7 May 1943)

- Units attached

- 1st Special Service Brigade

- 4th Special Service Brigade

- 1st Belgian Infantry Brigade

- Royal Netherlands Motorized Infantry Brigade

- Commanders

- Major-General Richard Gale (1943 - 1944)

- Major General Eric Bols (1944 - 1946)

- Major-General James Cassels (1946 - 1947)

- Major-General Hugh Stockwell (1947 - 1948)

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ The 1st Parachute Brigade had been called the "Rote Teufel" or "Red Devils" by the German troops they had fought in North Africa. The title was officially confirmed by General Sir Harold Alexander and henceforth applied to all British airborne troops.[1]

- ^ The 2nd Airborne Division, 4th Airborne Division and the 5th Airborne Division were deception divisions.[7]

- Citations

- ^ Otway, p.88

- ^ Saunders, p.189

- ^ "The 6th Airborne Division in Normandy". www.pegasusarchive.org. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Tugwell, p.123

- ^ a b Harclerode, p.223

- ^ Tugwell, p.202

- ^ Holt, pp.617, 827 and 915

- ^ Guard, p.37

- ^ "The British Airborne Assault". Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 30 January 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tugwell, p.209

- ^ Ford, pp.19–20

- ^ Historic England. "Syrencot House (1183033)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ a b Harclerode, p.225

- ^ a b c Guard, p.225

- ^ Gregory, p.125

- ^ Wilson, p.3

- ^ Wilson, p.4

- ^ Wilson, pp.212–213

- ^ Wilson, pp.214–215

- ^ Wilson, pp.216–217

- ^ a b Cole, p.209

- ^ Harclerode, p.226

- ^ Gregory 1979, p.100

- ^ Saunders 1971, p.143

- ^ Gregory 1979, p.101

- ^ Arthur, Max (11 May 1999). "Obituary, Major John Howard". The Independent. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Cole 1963, p.93

- ^ Harclerode, p.348

- ^ Otway 1990, pp.187–188

- ^ Saunders 1971, p.196

- ^ a b Saunders, p.279

- ^ Gregory, p.118

- ^ Hastings, p.239

- ^ a b Harclerode, p.549

- ^ Saunders, p.283

- ^ Gregory, p.85

- ^ Harclerode, p.551

- ^ Wilson, p.228

- ^ Wilson, p.250

- ^ Joslen, p. 106-107.

References

- Cole, Howard N (1963). On Wings of Healing: The Story of the Airborne Medical Services 1940–1960. Edinburgh, UK: William Blackwood. OCLC 29847628.

- Ferguson, Gregor (1984). The Paras 1940-84. Volume 1 of Elite series. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-573-1.

- Flint, Keith (2006). Airborne Armour: Tetrarch, Locust, Hamilcar and the 6th Airborne Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment 1938–1950. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company Ltd. ISBN 1-874622-37-X.

- Ford, Ken (2011). D-Day 1944 (3): Sword Beach & the British Airborne Landings. Oxford,UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-721-6.

- Gregory, Barry. Airborne Warfare 1918–1945. London: Phoebus Publishing. ISBN 0-7026-0053-9.

- Guard, Julie (2007). Airborne: World War II Paratroopers in Combat. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-196-6.

- Harclerode, Peter (2005). Wings Of War: Airborne Warfare 1918-1945. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-304-36730-3.

- Hastings, Max (2005). Armageddon: The Battle for Germany 1944-45. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-330-49062-1.

- Holt, Thaddeus (2004). The deceivers: Allied military deception in the Second World War. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-7432-5042-9.

- Lynch, Tim (2008). Silent Skies: Gliders At War 1939–1945. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 0-7503-0633-5.

- Moreman, Timothy Robert (2006). British Commandos 1940–46. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-986-X.

- Otway, Lieutenant-Colonel T.B.H (1990). The Second World War 1939-1945 Army — Airborne Forces. London: Imperial War Museum. ISBN 0-901627-57-7.

- Saunders, Hilary St George (1971). The Red Beret. London: New English Library. ISBN 0-450-01006-6.

- Shortt, James; McBride, Angus (1981). The Special Air Service. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0-85045-396-8.

- Smith, Claude (1992). History of the Glider Pilot Regiment. London: Pen & Sword Aviation. ISBN 1-84415-626-5.

- Tugwell, Maurice (1971). Airborne to battle: a History of Airborne Warfare, 1918-1971. London: Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0262-1.

- Wilson, Dare (2008). With the 6th Airborne Division in Palestine 1945–1948. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-771-6.

- British World War II divisions

- Airborne divisions of the United Kingdom

- Military units and formations established in 1943

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1948

- 1943 establishments in the United Kingdom

- 1948 disestablishments in the United Kingdom

- Military units and formations of the British Empire in World War II