Russian famine of 1921–1922: Difference between revisions

Improved readability. |

→International relief effort: improved readability |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

The main participants in the international relief effort were Hoover's [[American Relief Administration]],<ref>{{Citation | url = https://archive.org/details/gov.archives.arc.88967 | publisher = Newsreel | title= International news | volume = 442 | year = 1921}}</ref> along with other bodies such as the [[American Friends Service Committee]] and the [[International Save the Children Union]], which had the British [[Save the Children| Save the Children Fund]] as the major contributor.<ref>{{Citation | url = http://www.icrc.org/Web/Eng/siteeng0.nsf/html/5RFHJY | title = Famine in Russia: the hidden horrors of 1921 | publisher = ICRC| date = 2013-10-03 }}.</ref> Around ten million people were fed, with the bulk coming from the ARA, funded by the [[United States Congress]]; the European agencies co-ordinated by the ICRR fed two million people a day: the International Save the Children Union were feeding 375,000 in its centres at [[Saratov]] at the height of the operation.<ref name="Iconic">{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rRPHAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA68 | title=The Making of Humanitarian Visual Icons: On the 1921-1923 Russian Famine as Foundational Event | publisher=Palgrave Macmillan | work=Iconic Power: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life | date=3 January 2012 | accessdate=19 July 2014 | author=Kurusawa, Fuyuki | pages=68| isbn=9781137012869 }}</ref> <ref>{{Citation|chapter=FAMINE AND RELIEF 1921|date=2013-04-03|pages=102–102A|publisher=Routledge|isbn=9780203074473|doi=10.4324/9780203074473-102|title=The Routledge Atlas of Russian History}}</ref>The operation was hazardous — several workers died of cholera — and was not without its critics, including the London [[Daily Express]], which first denied the severity of the famine, and then argued that the money would better be spent in the United Kingdom.{{Sfn |Breen | 1994}} |

The main participants in the international relief effort were Hoover's [[American Relief Administration]],<ref>{{Citation | url = https://archive.org/details/gov.archives.arc.88967 | publisher = Newsreel | title= International news | volume = 442 | year = 1921}}</ref> along with other bodies such as the [[American Friends Service Committee]] and the [[International Save the Children Union]], which had the British [[Save the Children| Save the Children Fund]] as the major contributor.<ref>{{Citation | url = http://www.icrc.org/Web/Eng/siteeng0.nsf/html/5RFHJY | title = Famine in Russia: the hidden horrors of 1921 | publisher = ICRC| date = 2013-10-03 }}.</ref> Around ten million people were fed, with the bulk coming from the ARA, funded by the [[United States Congress]]; the European agencies co-ordinated by the ICRR fed two million people a day: the International Save the Children Union were feeding 375,000 in its centres at [[Saratov]] at the height of the operation.<ref name="Iconic">{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rRPHAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA68 | title=The Making of Humanitarian Visual Icons: On the 1921-1923 Russian Famine as Foundational Event | publisher=Palgrave Macmillan | work=Iconic Power: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life | date=3 January 2012 | accessdate=19 July 2014 | author=Kurusawa, Fuyuki | pages=68| isbn=9781137012869 }}</ref> <ref>{{Citation|chapter=FAMINE AND RELIEF 1921|date=2013-04-03|pages=102–102A|publisher=Routledge|isbn=9780203074473|doi=10.4324/9780203074473-102|title=The Routledge Atlas of Russian History}}</ref>The operation was hazardous — several workers died of cholera — and was not without its critics, including the London [[Daily Express]], which first denied the severity of the famine, and then argued that the money would better be spent in the United Kingdom.{{Sfn |Breen | 1994}} |

||

Throughout 1922 and 1923, as famine was still widespread and the ARA was still providing relief supplies, grain was exported by the Soviet government to raise funds for the revival of industry; this seriously endangered Western support for relief, and was one instance of a long-standing Soviet policy of valuing development above the lives of the peasantry. The new Soviet government insisted that if the AYA suspended relief |

Throughout 1922 and 1923, as famine was still widespread and the ARA was still providing relief supplies, grain was exported by the Soviet government to raise funds for the revival of industry; this seriously endangered Western support for relief, and was one instance of a long-standing Soviet policy of valuing development above the lives of the peasantry. The new Soviet government insisted that if the AYA suspended relief the ARA arrange a foreign loan for them of about $10,000,000 1923 dollars; the ARA was unable to do this, and continued to ship in food past the grain being sold abroad.<ref name="Ellman">{{Citation | author-link = | first = Michael | last = Ellman | url = |

||

http://www.paulbogdanor.com/left/soviet/famine/ellman1933.pdf | title = Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited | journal = Europe-Asia Studies | volume = 59 | issue = 4 |date=June 2007 | pages = 663–93 | format = [[PDF]] | doi=10.1080/09668130701291899}}.</ref><ref>{{Citation | first = Roman | last = Serbyn | contribution = The Famine of 1921–22 | title = Famine in the Ukraine, 1932–33 | place = Edmonton | year = 1986 | pages = 174–78}}.</ref> |

http://www.paulbogdanor.com/left/soviet/famine/ellman1933.pdf | title = Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited | journal = Europe-Asia Studies | volume = 59 | issue = 4 |date=June 2007 | pages = 663–93 | format = [[PDF]] | doi=10.1080/09668130701291899}}.</ref><ref>{{Citation | first = Roman | last = Serbyn | contribution = The Famine of 1921–22 | title = Famine in the Ukraine, 1932–33 | place = Edmonton | year = 1986 | pages = 174–78}}.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:52, 11 March 2019

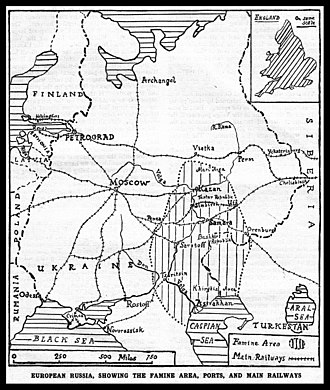

The Russian famine of 1921–22, also known as Povolzhye famine, was a severe famine in Russia which began in early spring of 1921 and lasted through 1922. This famine killed an estimated 5 million, primarily affecting the Volga and Ural River regions.[1][2]

The famine resulted from combined effects of economic disturbance through the disturbances of the Russian Revolution—and Russian Civil War with its policy of War Communism, especially prodrazvyorstka, exacerbated by rail systems that could not distribute food efficiently.

One of Russia's intermittent droughts in 1921 aggravated the situation to a national catastrophe. Hunger was so severe that it was likely seed-grain would be eaten rather than sown. At one point relief agencies had to give grain to railroad staff to get their supplies moved.

Origins

Before the famine began, Russia had suffered six and a half years of World War I and the Civil Wars of 1918–20, many of the conflicts fought inside Russia.[3]

Before the famine, all sides in the Russian Civil Wars of 1918–21—the Bolsheviks, the Whites, the Anarchists, the seceding nationalities—had provisioned themselves by seizing food from those who grew it, giving it to their armies and supporters, and denying it to their enemies. The Bolshevik government had requisitioned supplies from the peasantry for little or nothing in exchange. This led peasants to drastically reduce their crop production. According to the official Bolshevik position, which is still maintained by some modern Marxists, the rich peasants (kulaks) withheld their surplus grain to preserve their lives;[4] statistics indicate that most of the grain and the other food supplies passed through the black market.[5][6][7] The Bolsheviks believed peasants were actively trying to undermine the war effort. The Black Book of Communism asserts that Lenin ordered the seizure of the food peasants had grown for their own subsistence and their seed grain in retaliation for this "sabotage", leading to widespread peasant revolts.[8] In 1920, Lenin ordered increased emphasis on food requisitioning from the peasantry.

Aid from outside Russia was initially rejected. The American Relief Administration (ARA), which Herbert Hoover formed to help the victims of starvation of World War I, offered assistance to Lenin in 1919, on condition that they have full say over the Russian railway network and hand out food impartially to all. Lenin refused this as interference in Russian internal affairs.[3]

Lenin was eventually convinced—by this famine, the Kronstadt rebellion, large scale peasant uprisings such as the Tambov Rebellion, and the failure of a German general strike—to reverse his policy at home and abroad. He decreed the New Economic Policy on March 15, 1921. The famine also helped produce an opening to the West: Lenin allowed relief organizations to bring aid this time. War relief was no longer required in Western Europe, and the ARA had an organization set up in Poland, relieving the Polish famine which had begun in the winter of 1919–20.[9] Some peasants resorted to cannibalism.[10]

International relief effort

Although no official request for aid was issued, a committee of well-known people without obvious party affiliations was allowed to set up an appeal for assistance. In July 1921, the writer Maxim Gorky published an appeal to the outside world, saying that millions of lives were menaced by crop failure. At a conference in Geneva on 15 August organised by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the League of Red Cross Societies, the International Committee for Russian Relief (ICRR) was set up with Dr. Fridtjof Nansen as its High Commissioner. Nansen headed to Moscow, where he signed an agreement with Soviet Foreign Minister Georgy Chicherin that left the ICRR in full control of its operations. At the same time, fundraising for the famine relief operation began in earnest in Britain, with all the elements of a modern emergency relief operation — full-page newspaper advertisements, local collections, and a fundraising film shot in the famine area. By September, a ship had been despatched from London carrying 600 tons of supplies. The first feeding centre was opened in October in Saratov.

The main participants in the international relief effort were Hoover's American Relief Administration,[11] along with other bodies such as the American Friends Service Committee and the International Save the Children Union, which had the British Save the Children Fund as the major contributor.[12] Around ten million people were fed, with the bulk coming from the ARA, funded by the United States Congress; the European agencies co-ordinated by the ICRR fed two million people a day: the International Save the Children Union were feeding 375,000 in its centres at Saratov at the height of the operation.[13] [14]The operation was hazardous — several workers died of cholera — and was not without its critics, including the London Daily Express, which first denied the severity of the famine, and then argued that the money would better be spent in the United Kingdom.[15]

Throughout 1922 and 1923, as famine was still widespread and the ARA was still providing relief supplies, grain was exported by the Soviet government to raise funds for the revival of industry; this seriously endangered Western support for relief, and was one instance of a long-standing Soviet policy of valuing development above the lives of the peasantry. The new Soviet government insisted that if the AYA suspended relief the ARA arrange a foreign loan for them of about $10,000,000 1923 dollars; the ARA was unable to do this, and continued to ship in food past the grain being sold abroad.[16][17]

Death toll

As with other large-scale famines, the range of estimates is considerable. An official Soviet publication of the early 1920s concluded that about five million deaths occurred in 1921 from famine and related disease: this number is usually quoted in textbooks.[18] More conservative figures counted not more than a million, while another assessment, based on the ARA's medical division, spoke of two million.[19] On the other side of the scale, some sources spoke of ten million dead.[20] According to Betrand M. Patenaude, "such a number hardly seems extravagant after the many tens of millions of victims of war, famine, and terror in the twentieth century".[21]

Political uses

The famine came at the end of six and a half years of unrest and violence (first World War I, then the two Russian revolutions of 1917, then the Russian Civil War). Many different political and military factions were involved in those events, and most of them have been accused by their enemies of having contributed to, or even bearing sole responsibility for, the famine.[22]

Since 1922, Bolsheviks started a campaign of seizing church property. In 1922, over 4.5 million golden roubles of property were seized. Out of these, one million gold roubles were spent for famine relief.[23] In a secret March 19, 1922 letter to the Politburo, Lenin expressed an intention to seize several hundred million golden roubles for famine relief.[24]

In Lenin's secret letter to the Politburo, Lenin explains that the famine provides an opportunity against the church.[24] Richard Pipes argued that the famine was used politically as an excuse for the Bolshevik leadership to persecute the Orthodox Church, which held significant sway over much of the peasant populace.[25]

Russian anti-Bolshevik exiles in London, Paris, and elsewhere also used the famine as a media opportunity to highlight the iniquities of the Soviet regime in an effort to prevent trade with and official recognition of the Bolshevik Government.[26]

See also

- 1921 Mari wildfires

- 1921–22 famine in Tatarstan

- Kazakh famine of 1919–1922

- Famines in Russia and the USSR

- Fram (play)

- List of famines

- Pomgol

- Soviet famine of 1932–33

- Soviet famine of 1946–47

- American Relief Administration

References

- ^ "Famine of 1921-22". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. 2015-06-17. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- ^ Courtois, Stéphane; Werth, Nicolas; Panné, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartošek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. p. 123. ISBN 9780674076082.

- ^ a b Kennan 1961.

- ^ "An exchange of letters", Lenin's Secret Files (documentary), BBC, archived from the original on 2007-02-13

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - ^ Carr, EH, 1966, The Bolshevik Revolution 1917–1923, Part 2, p. 233.

- ^ Chase, WJ, 1987, Workers, Society and the Soviet State: Labour and Life in Moscow 1918–1929 pp. 26–27.

- ^ Nove, A, 1982, An Economic History of the USSR, p. 62, cited in Flewers, Paul. "War Communism in Retrospect".

- ^ Werth et al. 1999.

- ^ "WILSON RENEWS HUNGER LOAN PLEA". The New York Times. 28 January 1920. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ International news, vol. 442, Newsreel, 1921

- ^ Famine in Russia: the hidden horrors of 1921, ICRC, 2013-10-03.

- ^ Kurusawa, Fuyuki (3 January 2012). The Making of Humanitarian Visual Icons: On the 1921-1923 Russian Famine as Foundational Event. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 68. ISBN 9781137012869. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "FAMINE AND RELIEF 1921", The Routledge Atlas of Russian History, Routledge, 2013-04-03, pp. 102–102A, doi:10.4324/9780203074473-102, ISBN 9780203074473

- ^ Breen 1994.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (June 2007), "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited" (PDF), Europe-Asia Studies, 59 (4): 663–93, doi:10.1080/09668130701291899.

- ^ Serbyn, Roman (1986), "The Famine of 1921–22", Famine in the Ukraine, 1932–33, Edmonton, pp. 174–78

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ^ Norman Lowe. Mastering Twentieth-Century Russian History. Palgrave, 2002. P. 155.

- ^ Betrand M. Patenaude. The Big Show in Bololand. The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the Famine of 1921. Stanford University Press, 2002. P. 197.

- ^ How the U.S. saved a starving Soviet Russia: PBS film highlights Stanford scholar's research on the 1921-23 famine Stanford News

- ^ Patenaude, op. cit. p. 197-8.

- ^ Academia.edu

- ^ А. Г. Латышев. Рассекреченный Ленин. — 1-е изд. — М.: Март, 1996. — Pages 145—172. — 336 с. — 15 000 экз. — ISBN 5-88505-011-2.

- ^ a b Н.А. Кривова, "Власть и церковь в 1922-1925гг"

- ^ Pipes & 1995, pg. 415.

- ^ Jansen, Dinah (2015). After October: Russian Liberalism as a Work-in-Progress, 1917-1945. Kingston: Queen's University.

Bibliography

- Kennan, George Frost (1961), Russia and the West under Lenin and Stalin, Boston, pp. 141–50, 168, 179–85

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). Default reference for the historical and aftermath sections. - ———————— (1979), The Decline of Bismarck's European Order: Franco-Russian Relations, 1875–1890, Princeton, p. 387

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Fromkin, David: Peace to End All Peace (1989 hc) p. 360 (on Tsarist corruption and the closure of the Dardanelles).

- Furet, François (1999) [1995], Passing of an Illusion.

- Breen, Rodney (1994), "Saving Enemy Children: Save the Children's Russian Relief Organisation, 1921–1923", Disasters, 18 (3): 221–37, doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.1994.tb00309.x, PMID 7953492.

- Werth, Nicolas; Panné, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis (October 1999), Courtois, Stéphane (ed.), The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, pp. 92–97, 116–21, ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- Trotsky, Leon My Life (1930) Chapter 38 His advice to Lenin.

- Alexander N. Yakovlev. A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-300-08760-8 pp 155–56.

- Pipes, Richard (1995) [1994], Russia under the Bolshevik regime 1919–1924, London: Vintage, ISBN 978-0-679-76184-6.

- Jansen, Dinah (2015), "After October: Russian Liberalism as a Work-in Progress, 1917-1945" Kingston, Queen's University. PhD Dissertation.

Journal of British Studies 55 (July 2016): 519–537. doi:10.1017/jbr.2016.57 © The North American Conference on British Studies, 2016