Bernt Notke: Difference between revisions

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

[[File:Totentanz Lübeck 5.jpg|thumb|center|600px|The Lübeck ''Danse Macabre'' (detail, photographic reproduction, original destroyed)]] |

[[File:Totentanz Lübeck 5.jpg|thumb|center|600px|The Lübeck ''Danse Macabre'' (detail, photographic reproduction, original destroyed)]] |

||

{{Wide image|Totentanz LübeckR.jpg|2000px|''Lübecker Totentanz'' by [[Bernt Notke]] (around 1463, destroyed in a bombing raid in 1942)|alt=A mural depicting a chain of alternating living and dead dancers}} |

{{Wide image|Totentanz LübeckR.jpg|2000px|''Lübecker Totentanz'' by [[Bernt Notke]] (around 1463, destroyed in a bombing raid in 1942)|alt=A mural depicting a chain of alternating living and dead dancers}} |

||

[[File:The dance of death. Lithograph. Wellcome L0014664.jpg|thumb|center|A Lithograph of the lost artwork]] |

|||

====Tallinn ''Danse Macabre''==== |

====Tallinn ''Danse Macabre''==== |

||

Revision as of 13:09, 11 May 2019

ⓘ (c. 1440 – before May 1509) was a late Gothic artist, working in the Baltic region. He has been described as one of the foremost artists of his time in northern Europe.

Life

Very little is known about the life of Bernt Notke. The Notke family came from Tallinn (Estonia) and his father was probably the trader and ship-owner Michel Notke, who had his main business there. His mother was probably Michel's second wife Gertraut, who was from Visby. Bernt Notke was born in the small town of Lassan in Pomerania. He was married (at least once), but the name of his wife remains unknown; she died before he did and is not mentioned in his last will and testament. The couple is known to have had two daughters, one named Anneke and another whose name has not been preserved and who seems to have suffered from intellectual disability.[2][3]

He seems to have spent part of his youth in Flanders and there begun to learn his trade as an artist. He probably worked in the workshop of tapestry weaver Pasquier Grenier in Tournai, where he learned to work on art objects of a large scale. He probably also learned how to divide the labour in a workshop in a contemporary way there, as several of his own works were large, communal undertakings (see below). In the early 1460s he settled in Lübeck, where he would continue to live for the larger part of his life, although he would also intermittently live in Sweden and frequently traveled to cities around the Baltic Sea. He is mentioned in written sources for the first time by the city council of Lübeck on 14 April 1467. In 1479, he acquired a stone house on Breite Strasse, a prestigious address in Lübeck. He was in Stockholm for a prolonged period 1491 – 1497, during which time he for three years held the office of mint master of the realm in Sweden, but he left the city after the end of the regency of Sten Sture the Elder. After 1497, he lived in Lübeck until his death in 1509. In 1505, he acquired the title of Werkmeister at the Church of Saint Peter.[2][3][4][5][6]

Work

Artistic range

Medieval art differed from contemporary art in several ways, not least in that while modern artists often work in private studios, the production of medieval art was a communal undertaking in a workshop.[7] This was also the case with Bernt Notke, who was the head of such a workshop. During renovation of the large triumphal cross made by Notke in 1470–77, a note signed by Notke and five co-workers was discovered in a hollow part of one of the sculptures. It lists, apart from Notke himself, a carpenter, a painter and three other artisans.[2] The question whether Notke was first and foremost a painter, a woodworker or simply main organiser and entrepreneur is not clear.[6] He was called "painter" by the city council of Lübeck in a document from 1467.[2] He and his workshop produced art in the form of tapestries, wooden sculptures, and paintings. The main type of artwork produced by the workshop of Bernt Notke was altarpieces, incorporating both sculptures and painting.[2][5] Encyclopædia Britannica claims that he was also active as an engraver, but this claim is not found in other sources.[4]

Works by Notke

Lübeck Danse Macabre

It has been pointed out that already the first work known to have been made by Notke (between 1463 – 1466) is of unusual character: it was a 2 metres (6.6 ft) high and at least 26 metres (85 ft) long tapestry depicting the popular late medieval motif of the Danse Macabre (the dance of Death), made for a chapel of St. Mary's Church in Lübeck. It was lost or destroyed but survived in the form of a copy, made in 1701, until 1942, when it was destroyed during the allied bombing of Lübeck in World War II.[2][6]

Tallinn Danse Macabre

A second Danse Macabre, made at approximately the same time as the one in Lübeck, survives in part (c. 7 metres (23 ft)) Tallinn (Estonia), in St. Nicholas' Church. It has been suggested that the fragment in Tallinn may have been a piece cut out from the Lübeck Danse Macabre, but this is not certain. Regardless, both display the characteristic vivid expressionism that would become characteristic for Notke.[2][6]

Lübeck triumphal cross

In 1470 – 1478, Notke executed a very large sculpture group, a so-called triumphal cross (in English sometimes referred to as a rood) for display in Lübeck Cathedral. It consists of a total of 72 sculptures and is made of oak wood; dendrochronology has confirmed that the wood comes from oak trees felled near Lübeck c. 1470. The ensemble has been praised for its realism, monumentality and expressiveness. The patron ordering the art-piece was bishop Albert Krummedik.[2][6] Notke and his workshop also executed an elaborate gallery in Lübeck Cathedral, ordered by the mayor of Lübeck Andreas Geverdes.[2]

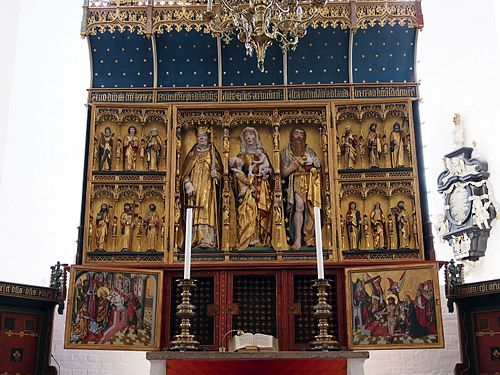

Aarhus Cathedral altarpiece

In 1479 the altarpiece of Aarhus Cathedral in Denmark was inaugurated, another monumental work from Notke's workshop. As with the Lübeck triumphal cross, it was commissioned by an important member of the clergy, bishop Jens Iversen (Lange). With its 12 metres (39 ft) of height, it was at the time the largest altarpiece in the Nordic countries. It consists of a large number of sculptures, where the central panel contains three large, dominating sculptures of Saint Anne, John the Baptist and Pope Clement I. The altarpiece is signed by Bernt Notke in three places. Influences from the early Northern Renaissance that began to spread from the Low Countries at this time can be traced in the realistic portraiture of some of the sculptures.[2][3]

High Altar in the Tallinn Church of the Holy Ghost

Another lavish altarpiece made by Notke is that of the Church of the Holy Ghost in Tallinn (Estonia), finished in 1483. It can be safely attributed to Notke also due to the fact that several letters by his hand have been preserved, in which he asks for the delayed payment for the altarpiece. The altarpiece is considerably more modest at a height of 3.5 metres (11 ft), but it is significant in that it is the earliest altarpiece in the Baltic region where the central panel is not a formal line-up of saints but rather depicts a biblical scene, in this case the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and Mary. Other novelties introduced to the art of the region through this altarpiece is the setting of the scene in an independent interior space (the scene takes place in a chapel) and, on the more technical side, a new system of folds in the drapery of the sculptures. It is the only of Notke's altarpieces that still retains the original paint and colour.[2][3]

Saint George and the Dragon (Stockholm)

Arguably the most famous sculpture by Notke is the free-standing sculpture of Saint George and the Dragon for Storkyrkan (the main church) in Stockholm inaugurated on New Year's Eve 1489. The statue had been commissioned by the Swedish regent Sten Sture the Elder, to commemorate Sture's victory over King Christian I of Denmark in the 1471 Battle of Brunkeberg.[2] There is a copy of the sculpture in St. Catherine's Church in Lübeck and one in bronze on Köpmantorget in Stockholm (inaugurated 1912). The statue inspired numerous other (albeit less elaborate) wooden depictions of the same subject in Sweden, Finland and Germany.[2][3]

Other works

A number of other unusual pieces of art in Sweden have been attributed to Notke's workshop. One is a portrait sculpture depicting Charles VIII of Sweden, today in Gripsholm Castle but originally possibly from the Riddarholm Church or part of the Saint George and the Dragon sculpture group (see above). The altarpiece in Rytterne Church in Västmanland in Sweden has also been attributed to Bernt Notke; it displays the Mass of Saint Gregory in an unusually realistic way. There is also a sculpture depicting Saint Eric in Strängnäs Cathedral, one depicting Thomas Becket (previously in Skepptuna Church but now in the Swedish History Museum) and an altarpiece in a church in Skellefteå in Sweden.[2] An altarpiece that has only survived in fragments, the Schonenfahrer altarpiece (currently in St. Anne's Museum Quarter, Lübeck) is attributed to Notke on stylistic grounds.[3]

Works previously attributed to Notke and lost works

Previously, an altarpiece in Trondenes Church near Harstad in Norway (the world's northernmost medieval church) was attributed to Notke, but the attribution has later been called into doubt.[8] Several other works from different countries around the Baltic Sea and in Belgium have also earlier been attributed to Notke, but without much certainty. A number of works by Notke's hand have also been lost. The main altarpiece of Uppsala Cathedral was made by Notke but destroyed in a fire in 1702 (the appearance of approximately half of the altarpiece is known through drawings). Made in c. 1471, this colossal altarpiece dedicated to St. Eric probably helped establish Notke's reputation in Scandinavia.[3] A large painting depicting the Mass of Saint Gregory for Saint Mary's Church in Lübeck is likewise known via depictions in the form of photographs, but the original was destroyed during the 1942 bombing of the city.[2]

Appraisal

Notke is widely recognised as an accomplished artist. He has been described as "one of the most important artists in eastern Germany and the surrounding area during the 15th century"[4] and "one of the most important late Gothic artists in northern Europe".[5] Philippe Dollinger states that if there is any artist who can be called "Hanseatic", it is Notke.[9] It has been said that he was the only artist in northern Germany who can be compared with the astonishing artistic developments in the south of the country, and at the same time that he is the foremost representative of late Gothic art in the Baltic region.[6] Jan Svanberg calls him one of the greatest late Gothic artists in Europe and considers especially the Saint George and the Dragon in Stockholm and the triumphal cross in Lübeck to be among the masterpieces of European sculpture.[2] Others note his "forceful personality" and compares Notke to a "North German antipode to Veit Stoss, both as a producer of altarpieces and as a personality".[3] Still others have been less exuberant in their praise and he has also been called "a routine producer of altarpieces".[3]

As noted above, Bernt Notke directly or indirectly influenced the evolution of art in the Baltic region, and influences derived from Notke can be seen in works of art as far south as Lüneburg (where a Danse Macabre by Hans Espenrad is considered a direct influence from Notke). At least two of his pupils are known by name, Heinrich Wylsynck (also known as Hynryk Wylsynck, fl. c. 1483, died 1533) and Henning van der Heide (ca. 1460 – 1521). Henning van der Heide is recognised as his most accomplished follower.[3]

Commemoration

A sculpture commemorating Bernt Notke stands in the harbour of his native town Lassan.[10]

Gallery

-

The Lübeck triumphal cross

-

Aarhus Cathedral altarpiece

-

High Altar in the Tallinn Church of the Holy Ghost

-

Saint George and the Dragon (Stockholm)

References

- ^ Gossman, Lionel. "Unwilling Moderns: The Nazarene Painters of the Nineteenth Century". Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, volume 2, issue 3. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Svanberg, Jan. "Bernt Notke". Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (in Swedish). Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Campbell, Gordon, ed. (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Northern Renaissance Art. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 718–719. ISBN 978-0-19-533-466-1.

- ^ a b c "Bernt Notke". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b c "Bernt Notke". Den Store Danske Encyklopædi (in Danish). Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Hartmut Krohm (1999), "Notke, Bernt", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 19, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 359–361; (full text online)

- ^ Steinhoff, Judith. "Medieval Workshops". University of Houston Art History Analysis. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "Om Trondenes kirke" (in Norwegian). Den Norske Kirke (Church of Norway). Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ Dollinger, Philippe (2012) [1964]. Die Hanse (in German). Stuttgart: Kröner Verlag. p. 361. ISBN 978-3-520-37106-5.

- ^ Banck, Claudia (2016). DuMont Reise-Taschenbuch Reiseführer Usedom (in German). Mair Dumont DE. p. 242. ISBN 9783616420813.

Further reading

- Hans Georg Gmelin. "Notke, Bernt." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, (accessed January 11, 2012).(subscription required)

- Kerstin Petermann: Bernt Notke. Arbeitsweise und Werkstattorganisation im späten Mittelalter. Berlin: Reimer 2000, ISBN 3-496-01217-X.

External links

Media related to Bernt Notke at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bernt Notke at Wikimedia Commons- Entry for Bernt Notke on the Union List of Artist Names