White cane: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 92.136.125.160 (talk) to last version by Graham87 |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{redirect|White stick|the community in the United States|White Stick, West Virginia}} |

{{redirect|White stick|the community in the United States|White Stick, West Virginia}} |

||

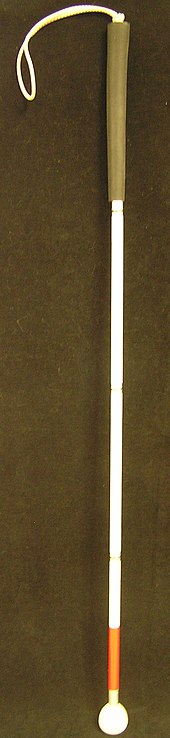

[[File:Long cane.jpg|thumb|upright|A long cane, the primary mobility tool for the visually impaired]] |

[[File:Long cane.jpg|thumb|upright|A long cane, the primary mobility tool for the visually impaired]] |

||

Revision as of 13:51, 15 August 2019

A white cane is a device used by many people who are blind or visually impaired. A white cane primarily allows its user to scan their surroundings for obstacles or orientation marks, but is also helpful for onlookers in identifying the user as blind or visually impaired and taking appropriate care. The latter is the reason for the cane's white colour, which in many jurisdictions is mandatory.

Variants

- Long cane: Designed primarily as a mobility tool used to detect objects in the path of a user. Cane length depends upon the height of a user, and traditionally extends from the floor to the user's sternum. It is the most well-known variant, though some organisations favor the use of much longer canes.[1]

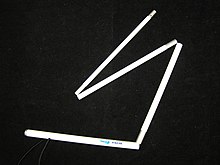

- Guide cane: A shorter cane, generally extending from the floor to the user's waist, with more limited potential as a mobility device. It is used to scan for kerbs and steps. The guide cane can also be used diagonally across the body for protection, warning the user of obstacles immediately ahead.

- Identification cane (sometimes shortened to ID cane and known as the symbol cane in British English): Used primarily to alert others that the user is visually impaired, but not to the extent where they require a long cane or other variant.[2] It is often lighter and shorter than the long cane, and has no use as a mobility tool.

- Support cane: Designed primarily to offer physical stability to a visually impaired user, the cane also works as a means of identification. It has very limited potential as a mobility device.

- Kiddie cane: This variant functions exactly the same as an adult's long cane but is designed for use by children, and is thus smaller and lighter.

- Green cane: Used in some countries, such as Argentina, to designate that the user has low vision, while the white cane designates that a user is completely blind.[3]

Mobility canes are often made from aluminium, graphite-reinforced plastic or other fibre-reinforced plastic, and can come with a wide variety of tips depending upon user preference.

White canes can be either collapsible or straight, with both versions having pros and cons. The National Federation of the Blind in the United States affirms that the lightness and greater length of the straight canes allows greater mobility and safety, though collapsible canes can be stored with more ease, giving them advantage in crowded areas such as classrooms and public events.[4][5]

History

Blind people have used canes as mobility tools for centuries,[6] but it was not until after World War I that the white cane was introduced.

In 1921 James Biggs, a photographer from Bristol who became blind after an accident and was uncomfortable with the amount of traffic around his home, painted his walking stick white to be more easily visible.[7]

In 1931 in France, Guilly d'Herbemont launched a national white stick movement for blind people. On February 7, 1931, Guilly d'Herbemont symbolically gave the first two white canes to blind people, in the presence of several French ministers. 5,000 more white canes were later sent to blind French veterans from World War I and blind civilians.[8]

In the United States, the introduction of the white cane is attributed to George A. Bonham of the Lions Clubs International.[9] In 1930, a Lions Club member watched as a man who was blind attempted to cross the street with a black cane that was barely visible to motorists against the dark pavement. The Lions decided to paint the cane white to make it more visible. In 1931, Lions Clubs International began a program promoting the use of white canes for people who are blind.

The first special white cane ordinance was passed in December 1930 in Peoria, Illinois granting blind pedestrians protections and the right-of-way while carrying a white cane.[10]

The long cane was improved upon by World War II veterans rehabilitation specialist, Richard E. Hoover, at Valley Forge Army Hospital.[11] In 1944, he took the Lions Club white cane (originally made of wood) and went around the hospital blindfolded for a week. During this time he developed what is now the standard method of "long cane" training or the Hoover Method. He is now called the "Father of the Lightweight Long Cane Technique." The basic technique is to swing the cane from the center of the body back and forth before the feet. The cane should be swept before the rear foot as the person steps. Before he taught other rehabilitators, or "orientors," his new technique he had a special commission to have light weight, long white canes made for the veterans of the European fronts.[12]

On October 6, 1964, a joint resolution of the Congress, HR 753, was signed into law authorizing the President of the United States to proclaim October 15 of each year as "White Cane Safety Day". President Lyndon Johnson was the first to make this proclamation.[13]

Legislation about canes

While the white cane is commonly accepted as a "symbol of blindness", different countries still have different rules concerning what constitutes a "cane for the blind".

In the United Kingdom, the white cane indicates that the individual has a visual impairment but normal hearing; with red bands added, it indicates that the user is deafblind.[2]

In the United States, laws vary from state to state, but in all cases, those carrying white canes are afforded the right-of-way when crossing a road. They are afforded the right to use their cane in any public place as well. In some cases, it is illegal for a non-blind person to use a white cane with the intent of being given right-of-way.[14][15]

In November 2002, Argentina passed a law recognizing the use of green canes by people with low vision, stating that the nation would "adopt from this law, the use of a green cane in the whole of Argentina as a means of orientation and mobility for people with low vision. It will have the same characteristics in weight, length, elastic grip and fluorescent ring as do white canes used by the blind."[3]

In Germany, people carrying a white cane are excepted from the Vertrauensgrundsatz (trust principle), therefore meaning that other traffic participants should not rely on them to adhere to all traffic regulations and practices. Although there is no general duty to mark oneself as blind or otherwise disabled, a blind or visually impaired person involved in a traffic accident without having marked themselves may be held responsible for damages unless they prove that their lack of marking was not causal or otherwise related to the accident.

Children and canes

In many countries, including the UK, a cane is not generally introduced to a child until they are between 7 and 10 years old. However, more recently canes have been started to be introduced as soon as a child learns to walk to aid development with great success.[16][17]

Joseph Cutter and Lilli Nielsen, pioneers in research on the development of blind and multiple-handicapped children, have begun to introduce new research on mobility in blind infants in children. Cutter's book, Independent Movement and Travel in Blind Children,[18] recommends a cane to be introduced as early as possible, so that the blind child learns to use it and move around naturally and organically, the same way a sighted child learns to walk. A longer cane, between nose and chin height, is recommended to compensate for a child's more immature grasp and tendency to hold the handle of the cane by the side instead of out in front. Mature cane technique should not be expected from a child, and style and technique can be refined as the child gets older.

See also

- GPS for the visually impaired

- Tactile paving

- Guide dog

- Guide horse

- Assistive cane

- Hoople (mobility aid)

References

- ^ Nichols, Allan (1995), Why Use the Long White Cane?, archived from the original on 2010-03-30

- ^ a b "The Cane Explained". RNIB.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b Rollano, Eduardo D.; Oyarzún, Juan C. (27 December 2002). "Personas con Baja Visión". Información Legislativa y Documental (in Spanish). Argentina: The Government of Argentina. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Code of Federal Regulations: 1985-1999

- ^ Education of the Visually Handicapped: The Official Publication of Association for Education of the Visually Handicapped, Volumes 1-3 ISBN 0-7246-3988-8 p. 13

- ^ Kelley, Pat (1999). "Historical Development of Orientation and Mobility as a Profession". OrientationAndMobility.org. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 'Mobility of Visually Impaired People: Fundamentals and ICT Assistive Technologies ISBN 978-3-319-54444-1 p. 363

- ^ Bailly, Claude (1990), "Les débuts de la canne blanche", l'Auxilaire des aveugles (in French), retrieved 20 January 2012

- ^ White Cane DayArchived October 27, 2002, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "White Cane History". American Council of the Blind. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ^ Koestler, Frances A. "Historical Chronologies , The Unseen Minority: A Social History of Blindness in the United States". American Printing House for the Blind. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Weiner, W.R., Welsh, R.L., & Blasch, B. B. (Eds.). (2010), Foundations of orientation and mobility (3rd ed., Vol. I), ISBN 978-0-89128-448-2

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) [page needed] - ^ ""White Cane Safety Day", National Federation of the Blind. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ http://www.nfb-nagdu.org/laws/usa/usa.htmlArchived October 10, 2003, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ http://acb.org/whitecane

- ^ http://www.worldaccessfortheblind.org/sites/default/files/Facilitating_Movement.pdf[page needed]

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-05-02. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2012-05-02 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Cutter, Joseph (2007), Independent Movement and Travel in Blind Children, ISBN 1-59311-603-9[page needed]

External links

![]() Media related to white canes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to white canes at Wikimedia Commons