Friedrich Freiherr von Hotze: Difference between revisions

m Task 15: language icon template(s) replaced (19×); |

HzgiUU149377 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

[[Category:18th-century Austrian military personnel]] |

[[Category:18th-century Austrian military personnel]] |

||

[[Category:Military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars killed in battle]] |

[[Category:Military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars killed in battle]] |

||

[[Category:Commanders Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa]] |

|||

Revision as of 15:31, 23 October 2020

Friedrich Freiherr von Hotze | |

|---|---|

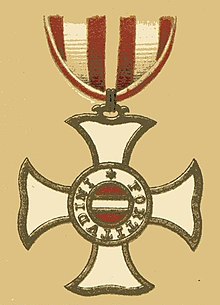

Hotze is wearing the Cross of the Order of....... | |

| Born | 20 April 1739 Richterswil, Canton of Zürich, Swiss Confederation |

| Died | 25 September 1799 (aged 60) Schänis on the Linth, Canton of St. Gallen |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Feldmarschall-leutnant |

| Battles / wars | Seven Years' War (service) Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) Austro-Turkish War of 1787 War of the Bavarian Succession French Revolutionary Wars |

| Awards | 1793, Knight's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa 1798, Commander's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa |

Friedrich Freiherr (Baron) von Hotze (20 April 1739 – 25 September 1799), was a Swiss-born general in the Austrian army during the French Revolutionary Wars. He campaigned in the Rhineland during the War of the First Coalition and in Switzerland in the War of the Second Coalition, notably at Battle of Winterthur in late May 1799, and the First Battle of Zurich in early June 1799. He was killed at the Second Battle of Zurich.

Hotze was born on 20 April 1739 in Richterswil in the Canton of Zürich, in the Old Swiss Confederacy (present-day Switzerland). As a boy, he graduated from the Carolinum in Zürich and pursued studies at the University of Tübingen. In 1758, he entered the military service of the Duke of Württemberg, and was promoted to captain of cavalry; he campaigned in the Seven Years' War, but saw no combat. Later, he served in the Russian army in Russia's War with Turkey, (1768–74).

His persistent attentiveness to Joseph II garnered for him a commission in the Austrian imperial army, and he served in the brief War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–79). A diligent and creative commander, he rose quickly through the ranks. His campaigning in the War of the First Coalition, particularly at the Battle of Würzburg, earned him the Knight's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa and, in 1798, the Commander's Cross. Archduke Charles placed him in full command of the center of the Austrian line at the First Battle of Zurich in 1799. He was killed by French musket fire in the morning mist near Schänis, in Canton of St. Gallen on 25 September 1799.

Childhood and early career

Friedrich Hotze was the second son of Johannes Hotze, a doctor and surgeon in Hessian military service and his Zürich-born wife, Juditha Gessner. Hotze came from an old Swiss family, and was a cousin of Heinrich Pestalozzi, the pedagogue and education reformer. As a young man, Hotze studied at the renowned Gymnasium Carolinum (Zürich).[1] Later he attended the University of Tübingen.[2] In October 1758, Hotze entered the military service of the Duke of Württemberg, in a Hussar regiment as an officer cadet (ensign).[3] By 1759, he had been promoted to lieutenant, and in 1761, to cavalry captain (or Rittmeister). He left the Duke's service during the disagreement between the Duke and the Württemberg Estates over financial matters involved in maintaining a standing army, and entered the service of the King of Prussia, where he remained until the end of the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). After service in Prussia, he took a brief vacation in Switzerland.[4]

In May 1768, Hotze entered the service of Catherine II, the Tsarina of Russia, but only as lieutenant of a regiment of dragoons, the so-called Ingermannland, named for the territory between Lake Peipus, the Narva River, and Lake Ladoga, in the old Grand Duchy of Novgorod.[5] He participated in several battles in Russia's on-going conflict with the Ottoman Empire, attracting the attention of Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov during the battle at Giurgiu, on the lower Danube, during which he was wounded. Suvarov praised him for his bravery and promoted him to major.[4]

Habsburg service

The war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire ended with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, signed on 21 July 1775. In 1776, Hotze returned to his home near Zürich. On the return journey, he stopped in Vienna, to present himself to the Emperor, Joseph II, and to seek an appointment as a major in the imperial Austrian army. When Joseph traveled to Hüningen near Basel, in the upper Rhine in 1777, Hotze once again presented himself, after which he finally secured a major's commission in the Cuirassiers Regiment 26, known as the Baron of Berlichingen (Freiherr von Berlichingen) regiment. His regiment served in the field during the brief War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–79). He served for a short time with the cuirassiers regiment Marquis de Voghera in Hungary, and returned with this regiment to Vienna in 1783. In 1784, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel (Oberstleutnant) and given command of the 1. Galican Lancers, which, in 1795, became the foundation of the 1. Lancers Regiment.[6]

Hotze's experience with military preparedness and organization gave him an advantage in establishing the lancers as a new combat arm. Recognizing the importance of lancers as part of the Austrian armed force, he embarked on an organizational and training program. The Emperor named him as commander of these corps, with the rank of a full colonel. In 1787, he returned temporarily to Russia, this time to establish a similar force in Catherine the Great's army. At the outbreak of the border war between the Ottoman Empire and Austria, he returned to Austria and took command of his regiment.[4]

French Revolutionary Wars

Initially, the rulers of Europe viewed the revolution in France as an event between the French king and his subjects, and not something in which they should interfere. In 1790, Leopold succeeded his brother Joseph as emperor and by 1791, he considered the situation surrounding his sister, Marie Antoinette, and her children, with greater alarm. In August 1791, in consultation with French émigré nobles and Frederick William II of Prussia, he issued the Declaration of Pillnitz, in which they declared the interest of the monarchs of Europe as one with the interests of Louis and his family. They threatened ambiguous, but quite serious, consequences if anything should happen to the royal family.[7]

The French Republican position became increasingly difficult. Compounding problems in international relations, French émigrés continued to agitate for support of a counter-revolution abroad. Chief among them were the Prince of Condé, his son, the Duke de Bourbon, and his grandson, the Duke d'Enghien. From their base in Koblenz, adjacent to the French-German border, they sought direct support for military intervention from the royal houses of Europe, and raised an army. On 20 April 1792, the French National Convention declared war on Austria. In this War of the First Coalition (1792–1798), France ranged itself against most of the European states sharing land or water borders with her, plus Portugal and the Ottoman Empire.[8]

War of First Coalition

In April 1792, Hotze and his regiment joined the autonomous Austrian Corps under Paul Anton II, Count von Esterházy in the Breisgau[9] although they took no part in any military clashes. Early in 1793, Hotze and his regiment were assigned to the Upper Rhine Army, commanded by General of Cavalry Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser, at which time Hotze was promoted to major general. As commander of the third column, he played an essential role the storming of the line at Wissembourg and Lauterburg, for which he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa. In the following year, 1794, he was assigned to the Army Corps of the Prince von Hohenlohe-Kirchberg, on the left bank of the Rhine, and later, from May–September at Heiligenstein on the Rhine, Schweigenheim, Westheim, and Landau in der Pfalz, against the French army commanded by the general of division Louis Desaix.[10]

In each of these assignments, Hotze proved himself as a confident and courageous general against the stronger French Army of the Moselle. In recognition, he was promoted to Feldmarschall-leutnant, a rank unusual for a man from a non-aristocratic family. He was also raised to the rank of baron (Freiherr) by Emperor Francis II. In the campaign of 1795, he served again under the command of Wurmser; his troops secured Rhineland positions near Mannheim, and later took part in engagements at Edighofen and Kaiserslautern.[11]

In the Battle of Neresheim (11 August 1796), Hotze commanded 13 battalions and 28 cavalry squadrons, a total of 13,300 men, and formed the center of Archduke Charles' line.[12] Although Hotze's force managed to push the French out of several villages, his force was not strong enough to follow up on his advantage.[13] Following the action at Neresheim, his force participated in the joint battles of Neumarkt and Lauf, followed by the Battle of Würzburg on 3 September 1796. During these consecutive actions, Hotze's organization and initiative led to the overwhelming of the French lines. For his actions in this campaign, he was awarded a promotion on 29 April 1797, and received the Commander's Cross of the Order of Maria Theresa.[4]

Peace and the Congress of Rastatt

The Coalition forces—Austria, Russia, Prussia, Great Britain, Sardinia, among others—achieved several victories at Verdun, Kaiserslautern, Neerwinden, Mainz, Amberg and Würzburg. While experiencing greater success in the north, in Italy, the Coalition's achievements were more limited. Despite the presence of the most experienced of the Austrian generals—Dagobert Wurmser—the Austrians could not lift the siege at Mantua, and the efforts of Napoleon in northern Italy pushed Austrian forces to the border of Habsburg lands. Napoleon dictated a cease-fire at Leoben on 17 April 1797, which led to the formal peace treaty, the Treaty of Campo Formio, which went into effect on 17 October 1797.[14]

The treaty called for meetings between the involved parties, to work out the exact territorial and remunerative details. These were to be convened at a small town in the mid-Rhineland, Rastatt, close to the French border. The primary combatants of the First Coalition, France and Austria, were highly suspicious of each other's motives, and the Congress quickly derailed in a mire of intrigue and diplomatic posturing. The French demanded more territory than originally agreed. The Austrians were reluctant to cede the designated territories. The Rastatt delegates could not, or would not, orchestrate the transfer of agreed upon territories to compensate the German princes for their losses. Compounding the Congress's problems, tensions grew between France and most of the First Coalition allies, either separately or jointly. Ferdinand of Naples refused to pay agreed-upon tribute to France, and his subjects followed this refusal with a rebellion. The French invaded Naples and established the Parthenopean Republic. A republican uprising in the Swiss cantons, encouraged by the French Republic which offered military support, led to the overthrow of the Swiss Confederation and the establishment of the Helvetic Republic.[15]

Other factors contributed to the rising tensions. On his way to Egypt in 1798, Napoleon had stopped on the Island of Malta and forcibly removed the Hospitallers from their possessions. This angered Paul, Tsar of Russia, who was the honorary head of the Order. Furthermore, the French Directory was convinced that the Austrians were conniving to start another war. Indeed, the weaker the French Republic seemed, the more seriously the Austrians, the Neapolitans, the Russians, and the English actually discussed this possibility.[16]

Outbreak of war in 1799

With the signing of the Treaty of Campo Formio on 17 October 1797, Hotze left Austrian service and returned to his home in Switzerland. Hardly had he arrived there when the government of the Swiss Confederation in Bern was overthrown, with the assistance of the French Directory. He returned to Austria, received a new commission and a new command.[17] He was already in the border regions between Switzerland, Austria, and Liechtenstein when the war broke out again in 1799. Archduke Charles of Austria, arguably among the best commanders of the House of Habsburg, had taken command of the Austrian army in late January. Although Charles was unhappy with the strategy set forward by his brother, the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, he had acquiesced to the less ambitious plan to which Francis and his advisers, the Aulic Council, had agreed: Austria would fight a defensive war and would maintain a continuous defensive line from the southern bank of the Danube, across the Swiss Cantons and into northern Italy. The archduke had stationed himself at Friedberg for the winter, 4.7 miles (8 km) east-south-east of Augsburg. His army settled into cantonments in the environs of Augsburg, extending south along the Lech River.[18]

As winter broke in 1799, on 1 March, General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan and his army of 25,000, the Army of the Danube, crossed the Rhine at Kehl.[19] Instructed to block the Austrians from access to the Swiss alpine passes, Jourdan planned to isolate the armies of the Coalition in Germany from allies in northern Italy, and prevent them from assisting one another. His was a preemptive strike. By crossing the Rhine in early March, Jourdan acted before the Charles' army could be reinforced by Austria's Russian allies, who had agreed to send 60,000 seasoned soldiers and their more-seasoned commander, Generalissimo Alexander Suvorov. Furthermore, if the French held the interior passes in Switzerland, they could not only prevent the Austrians from transferring troops between northern Italy and southwestern Germany, but could use the routes to move their own forces between the two theaters.[20]

The Army of the Danube, meeting little resistance, advanced through the Black Forest in three columns, through the Höllental (Hölle valley), via Oberkirch, and Freudenstadt; a fourth column advanced along the north shore of the Rhine, and eventually took a flanking position on the north shore of Lake Constance. Jourdan pushed across the Danube plain and took up position between Rottweil and Tuttlingen and eventually pushing toward the imperial city of Pfullendorf in Upper Swabia.[21] At the same time, the Army of Switzerland, under command of André Masséna, pushed toward the Grisons, intending to cut the Austrian lines of communication and relief at the mountain passes by Luziensteig and Feldkirch. A third Army of Italy, commanded by Louis Joseph Schérer, had already advanced into northern Italy, to deal with Ferdinand and the recalcitrant Neapolitans.[22]

War of the Second Coalition

When Hotze took up arms against the French in Switzerland, the revolutionary Swiss government in Bern revoked his Swiss citizenship. For the Coalition allies, though, his Swiss roots made him an ideal emissary between Vienna and Confederation sympathizers in Switzerland. He worked with William Wickham, and a Colonel Williams, an Englishman in Austrian service, to establish the Bodensee (Lake Constance) Flotilla.[23] As Feldmarschall-leutnant, he commanded 15,000 troops in the Vorarlberg against France's Army of Switzerland, commanded by André Masséna. After fortifying Feldkirch, he overwhelmed the fortress at St. Luzisteig, an important pass (elevation: 713 metres (2,339 ft)) in the Canton of Graubünden that links Swiss Confederation and Liechtenstein. Then, realizing that the main French army had crossed the Rhine and moved north of Lake Constance, he reorganized the defenses of Feldkirch, and deputed command to Franjo Jelačić, an able officer and commander. Hotze took 10,000 of the 15,500 troops designated for the defense of the Vorarlberg toward Lake Constance, intending to support Archduke Charles' left wing at the battles of Ostrach and, a few days later Stockach. Although his forces did not arrive in time to participate in the battles, the threat of their pending arrival influenced French planning.[24] In his absence, Jellacic's 5,500 men faced 12,000 under the command of generals of division Jean-Joseph Dessolles and Claude Lecourbe, inflicting enormous casualties (3000) on the French while suffering minimal losses (900) of their own.[25]

First Battle of Zurich

By mid-May 1799, the Austrians had wrested control of Switzerland from the French as the forces of Hotze and Count Heinrich von Bellegarde pushed them out of the Grisons; after pushing Jean-Baptiste Jourdan's force, the Army of the Danube, back to the Rhine, Archduke Charles' own sizable force—about 110,000 strong—crossed the Rhine, and prepared to join with the armies of Hotze and Bellegarde on the plains by Zürich. The French Army of Helvetia and the Army of the Danube, now both under the command of Masséna, tried to prevent this merger of the Austrian forces; in a preliminary action at Winterthur, the Austrians succeeded in pushing the French forces out of Winterthur, although they took high casualties.[4]

Once the union took place in the first two days of June, Archduke Charles, supported by Hotze's command, attacked French positions at Zürich.[26] In first Battle of Zürich, on 4–7 June 1799, Hotze commanded the entire left wing of Archduke Charles' army, which included 20 battalions of infantry, plus support artillery, and 27 squadrons of cavalry, in total, 19,000 men. Despite being wounded, he remained on the field. His troops not only pushed the French back, but harassed their retreat, forcing them across the Limmat river, where they took up defensive positions.[27]

Death at Second Battle of Zurich

In August 1799, Archduke Charles received orders from his brother, the Emperor, to withdraw the Austrian army across the Rhine.[28] While Charles could see this to be unreasonable—Alexander Suvorov had not yet reached central Switzerland, and it was folly to think that Alexander Korsakov's force of 30,000 and Hotze's 20,000 could hold all of the region until the arrival of the rest of the Russian force—the order was emphatic.[29] Charles delayed as long as he could, but in late August he withdrew his force across the Rhine and headed toward Philippsburg. When Suvorov heard of this breach of military common-sense, he wondered "the owl [referring to the Emperor] has either gone out of his mind, or he never had one."[30] The order was eventually reversed too late for the Archduke to stop his withdrawal.[31]

Unlike Korsakov, Hotze knew his military business, and he had organized a competent defense of the St. Gallen border, on Korsakov's left flank, reasoning, correctly, that Suvorov was on his way and needed St. Gallen as a safe haven after he passed through the Canton Schwyz.[32] On the morning of 25 September, Hotze and his chief of staff, Colonel Count von Plunkelt, conducted a reconnaissance ride near the village of Schänis, on the Linth river, only 32 kilometers (20 mi) from Richterswil, the village in which he had been born. In the heavy morning mist, they encountered a party French scouts from the 25th demi-brigade concealed behind a hedge. Summoned to surrender, Hotze wheeled around and spurred his horse, where both he and Colonel Plumkelt were killed by a volley of musketry.[4][33] Initially, Hotze was taken from the battlefield to the church in Schänis, where he was buried. In 1851, his body was moved to Bregenz and established in a monument there.[34]

Consequences of Hotze's death

Hotze was sorely missed. Despite mis-communication between and among the British, the Austrians and the Russians, the British miscalculation of the size of troops (consistently 10–25 percent higher than they actually were), the lack of Swiss volunteers, and failed promises of transport mules, Suvorov organized his impressive march across the Alps from northern Italy, counting on Korsakov and his Austrian allies to hold Zürich. His soldiers took the pass at St. Gotthard in a bayonet charge, and endured incredible hardships navigating the narrow trails of the Alps. By the time the Russian army reached Schwyz, preparing to descend from the mountains into the Zürich plain, Masséna's army already had crushed the incompetent Korsakov's force at Zürich, and, in Hotze's absence, Jean-de-Dieu Soult's French division overwhelmed the Austrian flank at Schänis and crossed the Linth unhindered.[35] When Suvorov cleared the mountains, he had nowhere to go; he was forced to withdraw in another arduous march into the Vorarlberg, where his starving and ragged army arrived in late October. Between Korsakov's inability to hold the French at Zürich, and Hotze's death at Schänis, the Swiss campaign degenerated to an utter shambles.[36]

Sources

Citations and notes

- ^ Established during Zwingli's 16th century school reform, the gymnasium provided classical instruction. It also was one of the components of the University of Zurich, founded in the mid-19th century. (in German) University of Zurich. Klassiches-Philologisches Seminar. Ab 13 November 2009. Accessed 14 December 2009.

- ^ His older brother, the doctor Johannes Hotze (1734–1801), studied medicine at Tübingen and the University of Leipzig. Johannes Hotze was one of the first professional doctors to practice medicine in the Zürich countryside. He also treated the emotionally disturbed, and offered in-house medical care for women in labor. He married Anna Elisabetha Pfenninger. (in German) Christoph Mörgeli. Hotz (Hotze), Johannes. Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz. 29 October 2007 edition. Accessed 18 October 2009.

- ^ (in German) Jens-Florian Ebert. Friedrich, Freiherr von Hotze. Die Österreichischen Generäle 1792–1815. Napoleon-online (German Version). Accessed 15 October 2009; (in German) Katja Hürlimann. Johann Konrad (Friedrich von Hotze) Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine. Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, 15 January 2008 edition, accessed 18 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f (in German) Ebert. Freiherr von Hotze.

- ^ Joseph Lins. "Saint Petersburg." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. Accessed 17 October 2009.

- ^ (in German) Ebert.Freiherr von Hotze.

- ^ Timothy Blanning. The French Revolutionary Wars. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-340-56911-5, pp. 41–59.

- ^ Blanning, pp. 44–59.

- ^ Kudrna, Leopold; Smith, Digby. "A Biographical Dictionary of all Austrian Generals during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars". Retrieved 2014-02-06.; Kudrna, Leopold; Smith, Digby. "Esterházy de Galántha, (Paul) Anton II. Anselm Fürst". Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- ^ (in German) Ebert. Freiherr von Hotze; (in German) Hürlimann, Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz.

- ^ (in German) Ebert, Freiherr von Hotze; (in German) Hürlimann, Hotze, in Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz.

- ^ Smith. "Neresheim." Data Book..

- ^ Rickard, John. Battle of Neresheim, 11 August 1796. History of War, Peter Antill, Tristan Dugdale-Pointon, and John Rickard, editors. Accessed 14 February 2009.

- ^ Blanning, pp. 41–59.

- ^ Blanning, pp. 230–232.

- ^ John Gallagher. Napoleon's enfant terrible: General Dominique Vandamme, Tulsa: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-8061-3875-6, p. 70.

- ^ (in German) Hürlimann, Hotze, in Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz.

- ^ Blanning, p. 232; Rothenberg, Gunther E. (2007). Napoleon's Great Adversaries: Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army 1792–1914. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Spellmount. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-86227-383-2.; Ramsey Weston Phipps. The Armies of the First French Republic, volume 5: The armies of the Rhine in Switzerland, Holland, Italy, Egypt and the coup d'etat of Brumaire, 1797-1799, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939, pp. 49–50.

- ^ John Young, D.D. A History of the Commencement, Progress, and Termination of the Late War between Great Britain and France which continued from the first day of February 1793 to the first of October 1801, in two volumes. Edinburg: Turnbull, 1802, vol. 2, p. 220.

- ^ Rothenberg, pp. 70–74.

- ^ Rothenberg, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Blanning, p. 232.

- ^ David Hollins. Austrian Commanders of the Napoleonic Wars, 1792–1815. London: Osprey, 2004, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Ramsey Weston Phipps. The Armies of the First French Republic, volume 5: "The armies of the Rhine in Switzerland, Holland, Italy, Egypt and the coup d'etat of Brumaire, 1797–1799." Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939, pp. 49–50.

- ^ The third action at Feldkirch, 23 March 1799. Digby Smith. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill, 1998. ISBN 1-85367-276-9 pp. 147–148.

- ^ Lawrence Shadwell. Mountain warfare illustrated by the campaign of 1799 in Switzerland : being a translation of the Swiss narrative, compiled from the works of the Archduke Charles, Jomini, and other...London: Henry S. King, 1875, p. 110; Blanning, p. 233.

- ^ (in German) Ebert, Freiherr von Hotze; (in German) Hürlimann, Hotze, in Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz; and Blanning, pp. 233–34.

- ^ Blanning, p. 252.

- ^ Blanning, pp. 253–53.

- ^ Philip Longworth. The art of victory: the life and achievements of Generalissimo Suvarov. London: Constable, 1965 ISBN 978-0-09-451170-5. p. 270.

- ^ Blanning, p. 253.

- ^ Blanning, p. 254; Longworth, pp. 269–271.

- ^ Shadwell Mountain Warfare p.207

- ^ (in German) Ebert. Freiherr von Hotze; (in German) Hürlimann, Hotze, in Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz.

- ^ Blanning, p. 254.

- ^ Blanning, p. 254; Young, D.D. vol. 2, pp. 220–228.

Bibliography

- Blanning, Timothy. The French Revolutionary Wars, New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-340-56911-5.

- Ebert, Jens-Florian, "Friedrich Freiherr von Hotze," Die Österreichischen Generäle 1792–1815. (in German) Accessed 15 October 2009.

- Hollins, David, Austrian Commanders of the Napoleonic Wars, 1792–1815, London: Osprey, 2004.

- Hürlimann, Katja, (Johann Konrad) "Friedrich von Hotze", (in German) Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, 15 January 2008 edition, accessed 18 October 2009.

- Kudrna, Leopold and Digby Smith. "Esterhazy." A biographical dictionary of all Austrian Generals in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1792–1815. At Napoleon Series, Robert Burnham, editor in chief. April 2008 version. Accessed 4 November 2009 -->

- Longworth, Philip, The art of victory: the life and achievements of Generalissimo Suvarov, London: Constable, 1965 ISBN 978-0-09-451170-5.

- Lins, Joseph. "Saint Petersburg.". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 17 Oct. 2009.

- Mörgeli, Christoph, "Johannes Hotze" (in German) Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz, 29 October 2007 edition, Accessed 18 October 2009.

- Meyer-Ott, Wilhelm (1853). Johann Konrad Hotz, später Friedrich Freiherr, k.k. Feldmarschallieutenant von Hotze (Google eBook) (in German). Zurich: Friedrich Schulthess. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston. The Armies of the First French Republic, volume 5: "The armies of the Rhine in Switzerland, Holland, Italy, Egypt and the coup d'etat of Brumaire, 1797–1799," Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Rickard, John. Battle of Neresheim, 11 August 1796. History of War online. Peter Antill, Tristan Dugdale-Pointon, and John Rickard, editors. Accessed 14 February 2009.

- Shadwell, Lawrence. Mountain warfare illustrated by the campaign of 1799 in Switzerland : being a translation of the Swiss narrative, compiled from the works of the Archduke Charles, Jomini, and other...London: Henry S. King, 1875.

- Smith, Digby. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill, 1998, ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Young, John, D.D. A History of the Commencement, Progress, and Termination of the Late War between Great Britain and France which continued from the first day of February 1793 to the first of October 1801, in two volumes. Edinburgh: Turnbull, 1802, vol. 2.

- University of Zurich. "Klassiches-Philologisches Seminar". (in German) Ab. 13 November 2009. Accessed 14 December 2009.

- 1739 births

- 1799 deaths

- People from Richterswil

- Austrian lieutenant field marshals

- Barons of Austria

- Military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars

- Austrian Empire military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars

- 18th-century Austrian military personnel

- Military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars killed in battle

- Commanders Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa