List of writing systems: Difference between revisions

→Linear nonfeatural alphabets: Wancho |

m →Abjads: Fixing links to disambiguation pages, improving links, other minor cleanup tasks |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

An [[abjad]] is a segmental script containing symbols for [[consonant]]s only, or where vowels are ''optionally'' written with [[diacritics]] ("pointing") or only written word-initially. |

An [[abjad]] is a segmental script containing symbols for [[consonant]]s only, or where vowels are ''optionally'' written with [[diacritics]] ("pointing") or only written word-initially. |

||

*[[Ancient North Arabian]]{{spaced ndash}} [[Dadanitic]], [[Dumaitic]], [[Hasaitic dialect|Hasaitic]], [[Hismaic]], [[Safaitic]], [[Taymanitic]], and [[Thamudic]] |

*[[Ancient North Arabian]]{{spaced ndash}} [[Dadanitic]], [[Dumaitic]], [[Hasaitic dialect|Hasaitic]], [[Hismaic]], [[Safaitic]], [[Taymanitic]], and [[Thamudic]] |

||

*[[Ancient South Arabian script|Ancient South Arabian]]{{spaced ndash}} [[Old South Arabian|Old South Arabian languages]] including [[Himyaritic language|Himyaritic]], [[Hadramautic language|Hadhramautic]], [[Minaean language|Minaean]],[[Sabaean language|Sabaean]] and [[Qatabanian language|Qatabanic]]; also the Ethiopic language [[Ge'ez]]. |

*[[Ancient South Arabian script|Ancient South Arabian]]{{spaced ndash}} [[Old South Arabian|Old South Arabian languages]] including [[Himyaritic language|Himyaritic]], [[Hadramautic language|Hadhramautic]], [[Minaean language|Minaean]], [[Sabaean language|Sabaean]] and [[Qatabanian language|Qatabanic]]; also the Ethiopic language [[Ge'ez]]. |

||

*[[Aramaic alphabet|Aramaic]], including [[Khwarezmian_language#Writing_system|Khwarezmian]] ({{sc|aka}} [[Chorasmian (Unicode block)|Chorasmian]]) |

*[[Aramaic alphabet|Aramaic]], including [[Khwarezmian_language#Writing_system|Khwarezmian]] ({{sc|aka}} [[Chorasmian (Unicode block)|Chorasmian]]) |

||

*[[Arabic script|Arabic]]{{spaced ndash}} [[Arabic language|Arabic]], [[Azeri language|Azeri]], [[Chittagonian language|Chittagonian]] (historically), [[Punjabi language|Punjabi]], [[Baluchi language|Baluchi]], [[Kashmiri language|Kashmiri]], [[Pashtu language|Pashto]], [[Persian language|Persian]], [[Kurdish language|Kurdish]] (vowels ''obligatory''), [[Sindhi language|Sindhi]], [[Uighur language|Uighur]] (vowels ''obligatory''), [[Urdu language|Urdu]], [[Malay language|Malay]] (as [[Jawi (script)|Jawi]]) and many other languages spoken in [[Africa]] and [[Western Asia|Western]], [[Central Asia|Central]], and [[Southeast Asia]], |

*[[Arabic script|Arabic]]{{spaced ndash}} [[Arabic language|Arabic]], [[Azeri language|Azeri]], [[Chittagonian language|Chittagonian]] (historically), [[Punjabi language|Punjabi]], [[Baluchi language|Baluchi]], [[Kashmiri language|Kashmiri]], [[Pashtu language|Pashto]], [[Persian language|Persian]], [[Kurdish language|Kurdish]] (vowels ''obligatory''), [[Sindhi language|Sindhi]], [[Uighur language|Uighur]] (vowels ''obligatory''), [[Urdu language|Urdu]], [[Malay language|Malay]] (as [[Jawi (script)|Jawi]]) and many other languages spoken in [[Africa]] and [[Western Asia|Western]], [[Central Asia|Central]], and [[Southeast Asia]], |

||

Revision as of 23:43, 18 April 2020

This is a list of writing systems (or scripts), classified according to some common distinguishing features.

The usual name of the script is given first; the name of the language(s) in which the script is written follows (in brackets), particularly in the case where the language name differs from the script name. Other informative or qualifying annotations for the script may also be provided.

Pictographic/ideographic writing systems

Template:Writing systems sidebar Ideographic scripts (in which graphemes are ideograms representing concepts or ideas, rather than a specific word in a language), and pictographic scripts (in which the graphemes are iconic pictures) are not thought to be able to express all that can be communicated by language, as argued by the linguists John DeFrancis and J. Marshall Unger. Essentially, they postulate that no full writing system can be completely pictographic or ideographic; it must be able to refer directly to a language in order to have the full expressive capacity of a language. Unger disputes claims made on behalf of Blissymbols in his 2004 book Ideogram.

Although a few pictographic or ideographic scripts exist today, there is no single way to read them, because there is no one-to-one correspondence between symbol and language. Hieroglyphs were commonly thought to be ideographic before they were translated, and to this day Chinese is often erroneously said to be ideographic.[1] In some cases of ideographic scripts, only the author of a text can read it with any certainty, and it may be said that they are interpreted rather than read. Such scripts often work best as mnemonic aids for oral texts, or as outlines that will be fleshed out in speech.

- Adinkra, traditionally used in modern Ghana, by groups such as the Asante people.

- Aztec – Nahuatl – Although some proper nouns have phonetic components.[2]

- Kaidā glyphs

- Mixtec – Mixtec

- Dongba – Naxi – Although this is often supplemented with syllabic Geba script.

- Ersu Shābā – Ersu

- Lusona, traditionally used by ethnic groups in modern Eastern Angola and North Western Zambia, and nearby regions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, especially by the Chokwe and Luchazi peoples.

- Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing – Míkmaq – Does have phonetic components, however.

- Nsibidi – Ekoi, Efik/Ibibio, Igbo

- Ojibwe "hieroglyphs"

- Siglas poveiras

- Testerian – used for missionary work in Mexico

- Other Mesoamerican writing systems with the exception of Maya Hieroglyphs.

There are also symbol systems used to represent things other than language, or to represent constructed languages. Some of these are

- Blissymbols – A constructed ideographic script used primarily in Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC).

- iConji – A constructed ideographic script used primarily in social networking

- Isotype (picture language)

- Sona language

- A wide variety of notations

Linear B and Asemic writing also incorporate ideograms.

Logographic writing systems

In logographic writing systems, glyphs represent words or morphemes (meaningful components of words, as in mean-ing-ful), rather than phonetic elements.

Note that no logographic script is composed solely of logograms. All contain graphemes that represent phonetic (sound-based) elements as well. These phonetic elements may be used on their own (to represent, for example, grammatical inflections or foreign words), or may serve as phonetic complements to a logogram (used to specify the sound of a logogram that might otherwise represent more than one word). In the case of Chinese, the phonetic element is built into the logogram itself; in Egyptian and Mayan, many glyphs are purely phonetic, whereas others function as either logograms or phonetic elements, depending on context. For this reason, many such scripts may be more properly referred to as logosyllabic or complex scripts; the terminology used is largely a product of custom in the field, and is to an extent arbitrary.

Consonant-based logographies

- Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, and Demotic – the writing systems of Ancient Egypt

Syllable-based logographies

- Anatolian hieroglyphs – Luwian

- Cuneiform – Sumerian, Akkadian, other Semitic languages, Elamite, Hittite, Luwian, Hurrian, and Urartian

- Chinese characters (Hanzi) – Chinese, Japanese (called Kanji), Korean (called Hanja), Vietnamese (called Chu Nom, obsolete), Zhuang Sawndip

- Eghap (or Bagam) script

- Mayan – Chorti, Yucatec, and other Classic Maya languages

- Yi (classical) – various Yi/Lolo languages

- Shui script – Shui language

Syllabaries

In a syllabary, graphemes represent syllables or moras. (Note that the 19th-century term syllabics usually referred to abugidas rather than true syllabaries.)

- Afaka – Ndyuka

- Alaska or Yugtun script – Central Yup'ik

- Bété

- Cherokee – Cherokee

- Cypriot – Arcadocypriot Greek

- Geba – Naxi

- Iban or Dunging script – Iban

- Kana – Japanese (although primarily based on moras rather than syllables)

- Kikakui – Mende

- Kpelle – Kpelle

- Linear B – Mycenean Greek

- Loma – Loma

- Masaba - Bambara

- Nüshu – Chinese

- Nwagu Aneke script – Igbo

- Vai – Vai

- Woleaian – Woleaian (a likely syllabary)

- Yi (modern) – various Yi/Lolo languages

Semi-syllabaries: Partly syllabic, partly alphabetic scripts

In most of these systems, some consonant-vowel combinations are written as syllables, but others are written as consonant plus vowel. In the case of Old Persian, all vowels were written regardless, so it was effectively a true alphabet despite its syllabic component. In Japanese a similar system plays a minor role in foreign borrowings; for example, [tu] is written [to]+[u], and [ti] as [te]+[i]. Paleohispanic semi-syllabaries behaved as a syllabary for the stop consonants and as an alphabet for the rest of consonants and vowels. The Tartessian or Southwestern script is typologically intermediate between a pure alphabet and the Paleohispanic full semi-syllabaries. Although the letter used to write a stop consonant was determined by the following vowel, as in a full semi-syllabary, the following vowel was also written, as in an alphabet. Some scholars treat Tartessian as a redundant semi-syllabary, others treat it as a redundant alphabet. Zhuyin is semi-syllabic in a different sense: it transcribes half syllables. That is, it has letters for syllable onsets and rimes (kan = "k-an") rather than for consonants and vowels (kan = "k-a-n").

- Paleohispanic semi-syllabaries – Paleo-Hispanic languages

- Old Persian cuneiform – Old Persian

- Bopomofo or Zhuyin fuhao – phonetic script for the different varieties of Chinese.

- Eskayan – Bohol, Philippines (a syllabary apparently based on an alphabet; some alphabetic characteristics remain)

- Bamum script – Bamum (a defective syllabary, with alphabetic principles used to fill the gaps)

- Khom script – Bahnaric languages, including Alak and Jru'. (Onset-rime script)

Segmental scripts

A segmental script has graphemes which represent the phonemes (basic unit of sound) of a language.

Note that there need not be (and rarely is) a one-to-one correspondence between the graphemes of the script and the phonemes of a language. A phoneme may be represented only by some combination or string of graphemes, the same phoneme may be represented by more than one distinct grapheme, the same grapheme may stand for more than one phoneme, or some combination of all of the above.

Segmental scripts may be further divided according to the types of phonemes they typically record:

Abjads

An abjad is a segmental script containing symbols for consonants only, or where vowels are optionally written with diacritics ("pointing") or only written word-initially.

- Ancient North Arabian – Dadanitic, Dumaitic, Hasaitic, Hismaic, Safaitic, Taymanitic, and Thamudic

- Ancient South Arabian – Old South Arabian languages including Himyaritic, Hadhramautic, Minaean, Sabaean and Qatabanic; also the Ethiopic language Ge'ez.

- Aramaic, including Khwarezmian (AKA Chorasmian)

- Arabic – Arabic, Azeri, Chittagonian (historically), Punjabi, Baluchi, Kashmiri, Pashto, Persian, Kurdish (vowels obligatory), Sindhi, Uighur (vowels obligatory), Urdu, Malay (as Jawi) and many other languages spoken in Africa and Western, Central, and Southeast Asia,

- Hebrew – Hebrew, Yiddish, and other Jewish languages

- Manichaean script

- Nabataean – the Nabataeans of Petra

- Pahlavi script – Middle Persian

- Phoenician – Phoenician and other Canaanite languages

- Proto-Canaanite

- Sogdian

- Samaritan (Old Hebrew) – Aramaic, Arabic, and Hebrew

- Syriac – Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, Syriac, Turoyo and other Neo-Aramaic languages

- Tifinagh – Tuareg

- Ugaritic – Ugaritic, Hurrian

True alphabets

A true alphabet contains separate letters (not diacritic marks) for both consonants and vowels.

Linear nonfeatural alphabets

Linear alphabets are composed of lines on a surface, such as ink on paper.

- Adlam – Fula

- Armenian – Armenian

- Avestan alphabet – Avestan

- Avoiuli – Raga

- Borama – Somali

- Carian – Carian

- Caucasian Albanian alphabet – Old Udi language

- Coorgi–Cox alphabet – Kodava

- Coptic – Egyptian

- Cyrillic – Eastern Slavic languages (Belarusian, Russian, Ukrainian), eastern South Slavic languages (Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbian), the other languages of Russia, Kazakh language, Kyrgyz language, Tajik language, Mongolian language. Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan are changing to the Latin alphabet but still have considerable use of Cyrillic. See Languages using Cyrillic.

- Eclectic Shorthand

- Elbasan – Albanian

- Fraser – Lisu

- Gabelsberger shorthand

- Garay – Wolof and Mandinka

- Georgian – Georgian and other Kartvelian languages

- Gjirokastër alphabet (also called Veso Bey) – Albanian

- Glagolitic – Old Church Slavonic

- Gothic – Gothic

- Greek – Greek, historically a variety of other languages

- Hanifi – Rohingya

- International Phonetic Alphabet

- Kaddare – Somali

- Latin AKA Roman – originally Latin language; most current western and central European languages, Turkic languages, sub-Saharan African languages, indigenous languages of the Americas, languages of maritime Southeast Asia and languages of Oceania use developments of it. Languages using a non-Latin writing system are generally also equipped with Romanization for transliteration or secondary use.

- Lycian – Lycian

- Lydian – Lydian

- Manchu – Manchu

- Mandaic – Mandaic dialect of Aramaic

- Mongolian – Mongolian

- Neo-Tifinagh – Tamazight

- Nyiakeng Puachue Hmong

- N'Ko – Maninka language, Bambara, Dyula language

- Ogham (Irish pronunciation: [oːm]) – Gaelic, Britannic, Pictish

- Ol Cemet' – Santali

- Old Hungarian (in Hungarian magyar rovásírás or székely-magyar rovásírás) – Hungarian

- Old Italic – a family of connected alphabets for the Etruscan, Oscan, Umbrian, Messapian, South Picene, Raetic, Venetic, Lepontic, Camunic languages

- Old Permic (also called Abur) – Komi

- Old Turkic – Turkic

- Old Uyghur alphabet – Uyghur

- Osmanya – Somali

- Runic alphabet – Germanic languages

- Sayaboury script (also called Eebee Hmong or Ntawv Puaj Txwm) – Hmong Daw

- Tai Lue – Lue

- Todhri – Albanian

- Tolong Siki – Kurukh

- Toto – Toto

- Vah – Bassa

- Vithkuqi AKA Beitha Kukju – Albanian

- Wancho – Wancho

- Yezidi script – Kurmanji

- Zaghawa – Zaghawa

- Zoulai – Zou (also has alphasyllabic characteristics)

Featural linear alphabets

A featural script has elements that indicate the components of articulation, such as bilabial consonants, fricatives, or back vowels. Scripts differ in how many features they indicate.

- Gregg Shorthand

- Hangul – Korean

- Osage – Osage

- Physioalphabet (a physiological alphabet)

- Shavian alphabet

- Tengwar (a fictional script)

- Visible Speech (a phonetic script)

- Stokoe notation for American Sign Language

- SignWriting and its descendents si5s and ASLwrite for sign languages

- Ditema tsa Dinoko AKA IsiBheqe SoHlamvu for Southern Bantu languages

Linear alphabets arranged into syllabic blocks

- Hangul – Korean

- Great Lakes Algonquian syllabics – Fox, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Ojibwe

- IsiBheqe SoHlamvu – Southern Bantu languages

Manual alphabets

Manual alphabets are frequently found as parts of sign languages. They are not used for writing per se, but for spelling out words while signing.

- American manual alphabet (used with slight modification in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Paraguay, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand)

- British manual alphabet (used in some of the Commonwealth of Nations, such as Australia and New Zealand)

- Catalan manual alphabet

- Chilean manual alphabet

- Chinese manual alphabet

- Dutch manual alphabet

- Ethiopian manual alphabet (an abugida)

- French manual alphabet

- Greek manual alphabet

- Icelandic manual alphabet (also used in Denmark)

- Indian manual alphabet (a true alphabet?; used in Devanagari and Gujarati areas)

- International manual alphabet (used in Germany, Austria, Norway, Finland)

- Iranian manual alphabet (an abjad; also used in Egypt)

- Israeli manual alphabet (an abjad)

- Italian manual alphabet

- Korean manual alphabet

- Latin American manual alphabets

- Polish manual alphabet

- Portuguese manual alphabet

- Romanian manual alphabet

- Russian manual alphabet (also used in Bulgaria and ex-Soviet states)

- Spanish manual alphabet (Madrid)

- Swedish manual alphabet

- Yugoslav manual alphabet

Other non-linear alphabets

These are other alphabets composed of something other than lines on a surface.

- Braille (Unified) – an embossed alphabet for the visually impaired, used with some extra letters to transcribe the Latin, Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic alphabets, as well as Chinese

- Braille (Korean)

- Braille (American) (defunct)

- New York Point – a defunct alternative to Braille

- International maritime signal flags (both alphabetic and ideographic)

- Morse code (International) – a trinary code of dashes, dots, and silence, whether transmitted by electricity, light, or sound) representing characters in the Latin alphabet.

- American Morse code (defunct)

- Optical telegraphy (defunct)

- Flag semaphore – (made by moving hand-held flags)

Abugidas

An abugida, or alphasyllabary, is a segmental script in which vowel sounds are denoted by diacritical marks or other systematic modification of the consonants. Generally, however, if a single letter is understood to have an inherent unwritten vowel, and only vowels other than this are written, then the system is classified as an abugida regardless of whether the vowels look like diacritics or full letters. The vast majority of abugidas are found from India to Southeast Asia and belong historically to the Brāhmī family, however the term is derived from the first characters of the abugida in Ge'ez: አ (A) ቡ (bu) ጊ (gi) ዳ (da) — (compare with alphabet). Unlike abjads, the diacritical marks and systemic modifications of the consonants are not optional.

Abugidas of the Brāhmī family

- Ahom

- Brahmi – Sanskrit, Prakrit,

- Balinese

- Batak – Toba and other Batak languages

- Baybayin – Formerly used for Ilokano, Kapampangan, Pangasinan, Tagalog, Bikol languages, Visayan languages, and possibly other Philippine languages

- Bengali and Assamese- Bengali, Assamese, Meithei, Bishnupriya Manipuri

- Bhaiksuki

- Buhid

- Burmese – Burmese, Karen languages, Mon, and Shan

- Cham

- Chakma

- Dehong – Dehong Dai

- Devanagari – Hindi, Sanskrit, Marathi, Nepali, and many other languages of northern India

- Dhives Akuru

- Grantha- Sanskrit

- Gujarati – Gujarati, Kutchi, Vasavi, Sanskrit, Avestan

- Gurmukhi script – Punjabi

- Hanuno’o

- Javanese

- Kaithi

- Kannada – Kannada, Tulu, Konkani, Kodava

- Kawi

- Khojki

- Khotanese

- Khudawadi

- Khmer

- Lao

- Lepcha

- Leke – Eastern Pwo, Western Pwo, and Karen

- Limbu

- Lontara’ – Buginese, Makassar, and Mandar

- Mahajani

- Malayalam

- Marchen - Zhang-Zhung

- Meetei Mayek

- Modi – Marathi

- Multani – Saraiki

- Nandinagari – Sanskrit

- New Tai Lue

- Odia

- Phags-pa – Mongolian, Chinese, and other languages of the Yuan Dynasty Mongol Empire

- Pracalit script AKA Newa – Nepal Bhasa, Sanskrit, Pali

- Pyu – Pyu

- Ranjana – Nepal Bhasa, Sanskrit

- Rejang

- Rencong

- Sharada – Sanskrit

- Siddham – Sanskrit

- Sinhala

- Saurashtra

- Soyombo

- Sundanese

- Sylheti Nagri – Bengali, Dobhashi, Sylheti

- Tagbanwa – Languages of Palawan

- Tai Le

- Tai Dam

- Tai Tham – Khün, and Northern Thai

- Takri

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Tibetan

- Tigalari – Sanskrit

- Tirhuta – used to write Maithili

- Tocharian

- Vatteluttu

- Zanabazar Square

- Zhang zhung scripts

Other abugidas

- Canadian Aboriginal syllabics – Cree syllabics (for Cree), Inuktitut syllabics (for Inuktitut), Ojibwe syllabics (for Ojibwe), and various systems for other languages of Canada. Derived scripts with identical operating principles but divergent character repertoires include Carrier and Blackfoot syllabics.

- Ethiopic – Amharic, Ge’ez, Tigrigna

- Kharoṣṭhī – Gandhari, Sanskrit

- Mandombe

- Meroitic – Meroë

- Pitman Shorthand

- Pollard script – Miao

- Sapalo script – Oromo

- Thaana – Dhivehi

- Thomas Natural Shorthand

Final consonant-diacritic abugidas

In at least one abugida, not only the vowel but any syllable-final consonant is written with a diacritic. That is, representing [o] with an under-ring, and final [k] with an over-cross, [sok] would be written as s̥̽.

Vowel-based abugidas

In a few abugidas, the vowels are basic, and the consonants secondary. If no consonant is written in Pahawh Hmong, it is understood to be /k/; consonants are written after the vowel they precede in speech. In Japanese Braille, the vowels but not the consonants have independent status, and it is the vowels which are modified when the consonant is y or w.

List of writing scripts by adoption

Undeciphered systems that may be writing

These systems have not been deciphered. In some cases, such as Meroitic, the sound values of the glyphs are known, but the texts still cannot be read because the language is not understood. Several of these systems, such as Epi-Olmec and Indus, are claimed to have been deciphered, but these claims have not been confirmed by independent researchers. In many cases it is doubtful that they are actually writing. The Vinča symbols appear to be proto-writing, and quipu may have recorded only numerical information. There are doubts that Indus is writing, and the Phaistos Disc has so little content or context that its nature is undetermined.

- Banpo symbols – Yangshao culture (perhaps proto-writing)

- Byblos syllabary – the city of Byblos

- Cretan hieroglyphs

- Indus – Indus Valley Civilization

- Isthmian (apparently logosyllabic)

- Jiahu symbols – Peiligang culture (perhaps proto-writing)

- Khitan small script – Khitan

- Linear A (a syllabary) – Minoan

- Mixtec – Mixtec (perhaps pictographic)

- Olmec – Olmec civilization (possibly the oldest Mesoamerican script)

- Para-Lydian script – Unknown language of Asia Minor; script appears related to the Lydian alphabet.

- Phaistos Disc (a unique text, very possibly not writing)

- Proto-Elamite – Elam (nearly as old as Sumerian)

- Proto-Sinaitic (likely an abjad)

- Quipu – Inca Empire (possibly numerical only)

- Rongorongo – Rapa Nui (perhaps a syllabary)

- Sidetic – Sidetic

- Zapotec – Zapotec (another old Mesoamerican script)

Undeciphered manuscripts

Comparatively recent manuscripts and other texts written in undeciphered (and often unidentified) writing systems; some of these may represent ciphers of known languages or hoaxes.

Other

Asemic writing is a writing-like form of artistic expression that generally lacks a specific semantic meaning, though it sometimes contains ideograms or pictograms.

Phonetic alphabets

This section lists alphabets used to transcribe phonetic or phonemic sound; not to be confused with spelling alphabets like the ICAO spelling alphabet. Some of these are used for transcription purposes by linguists; others are pedagogical in nature or intended as general orthographic reforms.

- International Phonetic Alphabet

- Americanist phonetic notation

- Uralic Phonetic Alphabet

- Deseret alphabet

- Unifon

- Shavian alphabet

Special alphabets

Alphabets may exist in forms other than visible symbols on a surface. Some of these are:

Tactile alphabets

Manual alphabets

For example:

Long-Distance Signaling

Alternative alphabets

Fictional writing systems

- Alteran

- Ath (alphabet)

- Aurebesh

- Cirth

- D'ni

- Gallifreyan

- Goa'uld

- Hymmnos

- Hylian

- Klingon

- On Beyond Zebra!

- Sarati

- Tengwar, used to write Quenya, Sindarin and other of J.R.R. Tolkien's Elvish languages

- The "Tennobet", used to write the Orokin language in the Digital Extremes MMO Warframe

- Unown

- Unnamed script used in Puella Magi Madoka Magica

- The written language in Hunter x Hunter

- Ancient Language used in the Tellius World of the series Fire Emblem

For animal use

- Yerkish uses "lexigrams" to communicate with non-human primates.

See also

- Artificial script

- List of languages by first written accounts

- Grapheme

- Unicode

- List of inventors of writing systems

- List of ISO 15924 codes

- Writing systems without word boundaries

- List of languages by writing system

Notes

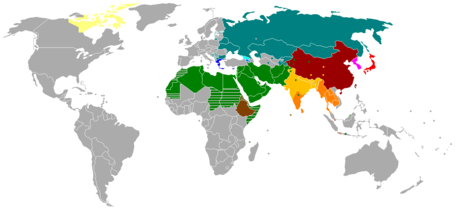

- ^ This maps shows languages official in the respective countries; if a country has an independent breakaway republic, both languages are shown. Moldova's sole official language is Romanian (Latin-based), but the unrecognized de facto independent republic of Transnistria uses three Cyrillic-based languages: Ukrainian, Russian, and Moldovan. Georgia's official languages are Georgian and Abkhazian (in Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia), the sparsely recognized de facto independent republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia use Cyrillic-based languages: Both republics use Russian. Additionally, Abkhazia also uses Abkhaz, and South Ossetia uses Ossetian. Azerbaijan's sole official language is Azerbaijani, but the unrecognized de facto independent republic of Nagorno-Karabakh uses Armenian as its sole language. Additionally, Serbia's sole official language is Cyrillic Serbian, but within the country, Latin script for Serbian is also widely used.

- ^ Difficult to determine, as it is used to write a very large number of languages with varying literacy rates among them.

- ^ Based on sum of 1.335 billion PRC citizens with a 92% literacy rate (1.22 billion), and 120 million Japanese Kanji users with a near-100% literacy rate.

- ^ Hanja has been banned in North Korea and is increasingly being phased out in South Korea. It is mainly used in official documents, newspapers, books, and signs to identify Chinese roots to Korean words.

- ^ January 2017 estimate. 2001 census reported that languages with more than 1 million native speakers that use Devanagari had a total amount of native speakers of 631.5 million. The January 2017 population estimate of India is 1.30 times that of the 2001 census, and it was estimated that the native speakers of Devanagari languages increased by the same proportion, i.e. to 820.95 million. This was multiplied by the literacy rate 74.04% as reported by the 2011 census. Since the literacy rate has increased since 2011 a + sign was added to this figure.

- ^ Based on Japanese population of roughly 120 million and a literacy rate near 100%.

- ^ Since around 1945 Javanese script has largely been supplanted by Latin script to write Javanese.

- ^ Excluding figures related to North Korea, which does not publish literacy rates.

- ^ Based on 61.11% literacy rate in Andhra Pradesh (according to government estimate) and 74 million Telugu speakers.

- ^ Tamil Nadu has an estimated 80% literacy rate and about 72 million Tamil speakers.

- ^ Sri Lanka Tamil and Moor population that use Tamil script. 92% literacy

- ^ Based on 60.38 million population and 79.31% literacy rate of Gujarat

- ^ An estimated 46 million Gujaratis live in India with 11 Gujarati-script newspapers in circulation.

- ^ An estimated 1 million Gujaratis live in Pakistan with 2 Gujarati-script newspapers in circulation.

- ^ Based on 46 million speakers of Kannada language, Tulu, Konkani, Kodava, Badaga in a state with a 75.6 literacy rate. url=http://updateox.com/india/26-populated-cities-karnataka-population-sex-ratio-literacy

- ^ Based on 42 million speakers of Burmese in a country (Myanmar) with a 92% literacy rate.

- ^ Spoken by 38 million people in the world.

- ^ Based on 40 million proficient speakers in a country with a 94% literacy rate.

- ^ Based on 29 million Eastern Punjabi speakers and 75% literacy rate

- ^ Based on 30 million speakers of Lao in a country with a 73% literacy.

- ^ Based on 32 million speakers of Odia in a country with a 65% literacy.

- ^ Based on 30 million native speakers of Amharic and Tigrinya and a 60% literacy rate.

- ^ Based on 15.6 million Sinhalese language speakers and a 92% literacy rate in Sri Lanka.

- ^ Hebrew has over 9 million speakers, including other Jewish languages and Jewish population outside Israel, where the Hebrew script is used by Jews for religious purposes worldwide.

- ^ Based on 15 million Khmer speakers with 73.6% literacy rate.

- ^ Most schoolchildren worldwide and hundreds of millions[citation needed] of scientists, mathematicians and engineers use the Greek alphabet in mathematical/technical notation. See Greek letters used in mathematics, science, and engineering

References

- ^ Halliday, M.A.K., Spoken and written language, Deakin University Press, 1985, p.19

- ^ Smith, Mike (1997). The Aztecs. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23015-7.

- ^ http://www.omniglot.com/writing/bengali.htm

External links

- Omniglot: a guide to writing systems

- Ancient Scripts: Home:(Site with some introduction to different writing systems and group them into origins/types/families/regions/timeline/A to Z)

- Michael Everson's Alphabets of Europe

- Deseret Alphabet

- ScriptSource - a dynamic, collaborative reference to the writing systems of the world