Rapid application development: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m error fixing |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

== Pros and cons of rapid application development == |

== Pros and cons of rapid application development == |

||

In modern Information Technology environments, many systems are now built using some degree of Rapid Application Development<ref>{{cite web |

In modern Information Technology environments, many systems are now built using some degree of Rapid Application Development<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gartner.com.br/tecnologias_empresariais/pdfs/brl37l_a3.pdf|title= The Disintegration of AD: Putting it Back Together Again|publisher=gartner.com.br|accessdate=2010-04-13}}</ref> (not necessarily the James Martin approach). In addition to Martin's method, [[Agile methods]] and the [[Rational Unified Process]] are often used for RAD development. |

||

The purported advantages of RAD include: |

The purported advantages of RAD include: |

||

Revision as of 12:38, 27 October 2020

| Part of a series on |

| Software development |

|---|

Rapid-application development (RAD), also called rapid-application building (RAB), is both a general term for adaptive software development approaches, and the name for James Martin's approach to rapid development. In general, RAD approaches to software development put less emphasis on planning and more emphasis on an adaptive process. Prototypes are often used in addition to or sometimes even in place of design specifications.

RAD is especially well suited for (although not limited to) developing software that is driven by user interface requirements. Graphical user interface builders are often called rapid application development tools. Other approaches to rapid development include the adaptive, agile, spiral, and unified models.

History

Rapid application development was a response to plan-driven waterfall processes, developed in the 1970s and 1980s, such as the Structured Systems Analysis and Design Method (SSADM). One of the problems with these methods is that they were based on a traditional engineering model used to design and build things like bridges and buildings. Software is an inherently different kind of artifact. Software can radically change the entire process used to solve a problem. As a result, knowledge gained from the development process itself can feed back to the requirements and design of the solution.[1] Plan-driven approaches attempt to rigidly define the requirements, the solution, and the plan to implement it, and have a process that discourages changes. RAD approaches, on the other hand, recognize that software development is a knowledge intensive process and provide flexible processes that help take advantage of knowledge gained during the project to improve or adapt the solution.

The first such RAD alternative was developed by Barry Boehm and was known as the spiral model. Boehm and other subsequent RAD approaches emphasized developing prototypes as well as or instead of rigorous design specifications. Prototypes had several advantages over traditional specifications:

- Risk reduction. A prototype could test some of the most difficult potential parts of the system early on in the life-cycle. This can provide valuable information as to the feasibility of a design and can prevent the team from pursuing solutions that turn out to be too complex or time consuming to implement. This benefit of finding problems earlier in the life-cycle rather than later was a key benefit of the RAD approach. The earlier a problem can be found the cheaper it is to address.

- Users are better at using and reacting than at creating specifications. In the waterfall model it was common for a user to sign off on a set of requirements but then when presented with an implemented system to suddenly realize that a given design lacked some critical features or was too complex. In general most users give much more useful feedback when they can experience a prototype of the running system rather than abstractly define what that system should be.

- Prototypes can be usable and can evolve into the completed product. One approach used in some RAD methods was to build the system as a series of prototypes that evolve from minimal functionality to moderately useful to the final completed system. The advantage of this besides the two advantages above was that the users could get useful business functionality much earlier in the process.[2]

Starting with the ideas of Barry Boehm and others, James Martin developed the rapid application development approach during the 1980s at IBM and finally formalized it by publishing a book in 1991, Rapid Application Development. This has resulted in some confusion over the term RAD even among IT professionals. It is important to distinguish between RAD as a general alternative to the waterfall model and RAD as the specific method created by Martin. The Martin method was tailored toward knowledge intensive and UI intensive business systems.

These ideas were further developed and improved upon by RAD pioneers like James Kerr and Richard Hunter, who together wrote the seminal book on the subject, Inside RAD,[3] which followed the journey of a RAD project manager as he drove and refined the RAD Methodology in real-time on an actual RAD project. These practitioners, and those like them, helped RAD gain popularity as an alternative to traditional systems project life cycle approaches.

The RAD approach also matured during the period of peak interest in business re-engineering. The idea of business process re-engineering was to radically rethink core business processes such as sales and customer support with the new capabilities of Information Technology in mind. RAD was often an essential part of larger business re engineering programs. The rapid prototyping approach of RAD was a key tool to help users and analysts "think out of the box" about innovative ways that technology might radically reinvent a core business process.[4][5]

The James Martin RAD method

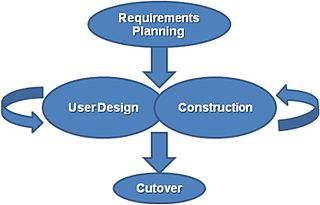

The James Martin approach to RAD divides the process into four distinct phases:

- Requirements planning phase – combines elements of the system planning and systems analysis phases of the Systems Development Life Cycle (SDLC). Users, managers, and IT staff members discuss and agree on business needs, project scope, constraints, and system requirements. It ends when the team agrees on the key issues and obtains management authorization to continue.

- User design phase – during this phase, users interact with systems analysts and develop models and prototypes that represent all system processes, inputs, and outputs. The RAD groups or subgroups typically use a combination of Joint Application Development (JAD) techniques and CASE tools to translate user needs into working models. User Design is a continuous interactive process that allows users to understand, modify, and eventually approve a working model of the system that meets their needs.

- Construction phase – focuses on program and application development task similar to the SDLC. In RAD, however, users continue to participate and can still suggest changes or improvements as actual screens or reports are developed. Its tasks are programming and application development, coding, unit-integration and system testing.

- Cutover phase – resembles the final tasks in the SDLC implementation phase, including data conversion, testing, changeover to the new system, and user training. Compared with traditional methods, the entire process is compressed. As a result, the new system is built, delivered, and placed in operation much sooner.[6]

Pros and cons of rapid application development

In modern Information Technology environments, many systems are now built using some degree of Rapid Application Development[7] (not necessarily the James Martin approach). In addition to Martin's method, Agile methods and the Rational Unified Process are often used for RAD development.

The purported advantages of RAD include:

- Better quality. By having users interact with evolving prototypes the business functionality from a RAD project can often be much higher than that achieved via a waterfall model. The software can be more usable and has a better chance to focus on business problems that are critical to end users rather than technical problems of interest to developers. However, this excludes other categories of what are usually known as Non-functional requirements (AKA constraints or quality attributes) including security and portability.

- Risk control. Although much of the literature on RAD focuses on speed and user involvement a critical feature of RAD done correctly is risk mitigation. It's worth remembering that Boehm initially characterized the spiral model as a risk based approach. A RAD approach can focus in early on the key risk factors and adjust to them based on empirical evidence collected in the early part of the process. E.g., the complexity of prototyping some of the most complex parts of the system.

- More projects completed on time and within budget. By focusing on the development of incremental units the chances for catastrophic failures that have dogged large waterfall projects is reduced. In the Waterfall model it was common to come to a realization after six months or more of analysis and development that required a radical rethinking of the entire system. With RAD this kind of information can be discovered and acted upon earlier in the process.[2][8]

The disadvantages of RAD include:

- The risk of a new approach. For most IT shops RAD was a new approach that required experienced professionals to rethink the way they worked. Humans are virtually always averse to change and any project undertaken with new tools or methods will be more likely to fail the first time simply due to the requirement for the team to learn.

- Lack of emphasis on Non-functional requirements, which are often not visible to the end user in normal operation.

- Requires time of scarce resources. One thing virtually all approaches to RAD have in common is that there is much more interaction throughout the entire life-cycle between users and developers. In the waterfall model, users would define requirements and then mostly go away as developers created the system. In RAD users are involved from the beginning and through virtually the entire project. This requires that the business is willing to invest the time of application domain experts. The paradox is that the better the expert, the more they are familiar with their domain, the more they are required to actually run the business and it may be difficult to convince their supervisors to invest their time. Without such commitments RAD projects will not succeed.

- Less control. One of the advantages of RAD is that it provides a flexible adaptable process. The ideal is to be able to adapt quickly to both problems and opportunities. There is an inevitable trade-off between flexibility and control, more of one means less of the other. If a project (e.g. life-critical software) values control more than agility RAD is not appropriate.

- Poor design. The focus on prototypes can be taken too far in some cases resulting in a "hack and test" methodology where developers are constantly making minor changes to individual components and ignoring system architecture issues that could result in a better overall design. This can especially be an issue for methodologies such as Martin's that focus so heavily on the user interface of the system.[9]

- Lack of scalability. RAD typically focuses on small to medium-sized project teams. The other issues cited above (less design and control) present special challenges when using a RAD approach for very large scale systems.[10][11][12]

See also

- Flow-based programming

- Low-code development platforms

- Lean software development

- Platform as a service

References

- ^ Brooks, Fred (1986). Kugler, H.J. (ed.). No Silver Bullet Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering (PDF). Information Processing '86. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V (North-Holland). ISBN 0-444-70077-3. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ a b Boehm, Barry (May 1988). "A Spiral Model of Software Development" (PDF). IEEE Computer. doi:10.1109/2.59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ Kerr, James M.; Hunter, Richard (1993). Inside RAD: How to Build a Fully Functional System in 90 Days or Less. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-034223-7.

- ^ Drucker, Peter (3 November 2009). Post-Capitalist Society. Harper Collins e-books. ISBN 978-0887306204.

- ^ Martin, James (1991). Rapid Application Development. Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-376775-8.

- ^ Martin, James (1991). Rapid Application Development. Macmillan. pp. 81–90. ISBN 0-02-376775-8.

- ^ "The Disintegration of AD: Putting it Back Together Again" (PDF). gartner.com.br. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Beck, Kent (2000). Extreme Programming Explained. Addison Wesley. pp. 3–7. ISBN 0201616416.

- ^ Gerber, Aurona; Van Der Merwe, Alta; Alberts, Ronell (16–18 November 2007). "Practical Implications of Rapid Development Methodologies". Proceedings of the Computer Science and Information technology Education Conference, CSITEd-2007. Computer Science and IT Education Conference. Mauritius. pp. 233–245. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.100.645. ISBN 978-99903-87-47-6.

- ^ Andrew Begel, Nachiappan Nagappan (September 2007). "Usage and Perceptions of Agile Software Development in an Industrial Context: An Exploratory Study" (PDF). doi:10.1109/esem.2007.12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Maximilien, E.M.; Williams, L. (2003). "Assessing test-driven development at IBM". 25th International Conference on Software Engineering, 2003. Proceedings. pp. 564–569. doi:10.1109/icse.2003.1201238. ISBN 0-7695-1877-X.

- ^ Stephens, Matt; Rosenberg, Doug (2003). Extreme Programming Refactored: The Case Against XP. doi:10.1007/978-1-4302-0810-5. ISBN 978-1-59059-096-6.

Further reading

- Steve McConnell (1996). Rapid Development: Taming Wild Software Schedules, Microsoft Press Books, ISBN 978-1-55615-900-8

- Kerr, James M.; Hunter, Richard (1993). Inside RAD: How to Build a Fully Functional System in 90 Days or Less. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-034223-7.

- Ellen Gottesdiener (1995). "RAD Realities: Beyond the Hype to How RAD Really Works" Application Development Trends

- Ken Schwaber (1996). Agile Project Management with Scrum, Microsoft Press Books, ISBN 978-0-7356-1993-7

- Steve McConnell (2003). Professional Software Development: Shorter Schedules, Higher Quality Products, More Successful Projects, Enhanced Careers, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-0-321-19367-4

- Dean Leffingwell (2007). Scaling Software Agility: Best Practices for Large Enterprises, Addison-Wesley Professional, ISBN 978-0-321-45819-3

- Scott Stiner (2016). Forbes List: "Rapid Application Development (RAD): A Smart, Quick And Valueable Process For Software Developers"