March 2012 North American heat wave: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Add: work. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were actually parameter name changes. | You can use this bot yourself. Report bugs here. | Suggested by AManWithNoPlan | All pages linked from cached copy of User:AManWithNoPlan/sandbox4 | via #UCB_webform_linked 2080/4000 |

m v2.04b - Bot T20 CW#61 - Fix errors for CW project (Reference before punctuation) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

It is no coincidence that this heat wave occurred immediately following "the biggest dose of heat we've received from a solar storm since 2005"<ref>https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2012/22mar_saber/?fbclid=IwAR34u_W8r5_XyBEEZkRDo9_PGatR0zaDAa5eO7ZjxyFl98gKjt1_LSkx6x8</ref><ref>https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/news/saber-solarstorm.html?fbclid=IwAR17_RP7C-MDUDgsKHlqL_UOFaVSEfVAZ-sxsPknqYq1XunMpcsQb9gblMw</ref> This came from a "flurry of eruptions on the sun...March 8th through 10th, the thermosphere absorbed 26 billion kWh of energy" Ironically, the scientist of the study speculated that CO, one of "the two most efficient coolants[not climate warmers] in the thermosphere, reradiated 95% of that total back into space" This phenomena repeated itself in the summer of 2012 with a series of M and X class flares resulting in another heat wave. |

It is no coincidence that this heat wave occurred immediately following "the biggest dose of heat we've received from a solar storm since 2005"<ref>https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2012/22mar_saber/?fbclid=IwAR34u_W8r5_XyBEEZkRDo9_PGatR0zaDAa5eO7ZjxyFl98gKjt1_LSkx6x8</ref><ref>https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/news/saber-solarstorm.html?fbclid=IwAR17_RP7C-MDUDgsKHlqL_UOFaVSEfVAZ-sxsPknqYq1XunMpcsQb9gblMw</ref> This came from a "flurry of eruptions on the sun...March 8th through 10th, the thermosphere absorbed 26 billion kWh of energy" Ironically, the scientist of the study speculated that CO, one of "the two most efficient coolants[not climate warmers] in the thermosphere, reradiated 95% of that total back into space" This phenomena repeated itself in the summer of 2012 with a series of M and X class flares resulting in another heat wave. |

||

The primary<ref>unsupported</ref> |

The primary,<ref>unsupported</ref> immediate cause of the heat wave was a buckled jet stream caused by an abnormally strong high pressure ridge atop the Eastern United States and an unusually strong and slow-moving low pressure trough across the West, which brought with it below-average temperatures and snow. The tight pressure gradient allowed for an intense southerly jet to form, which transported warm, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico northward, with the moisture having an insulating effect during the night. The ridge also deflected storm systems northward away from the Eastern U.S. and kept skies clear, allowing further daytime radiative heating to occur. |

||

In addition, the [[North Atlantic oscillation]] was in a strongly positive phase during the heat wave, which often foreshadows above average temperatures in the Eastern U.S. The Madden-Julian oscillation also entered a phase correlated with warm temperatures in the U.S. East.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.weather.gov/media/lot/events/March2012/March_Heatwave_2012_final.pdf|title=The Historic March 2012 Heat Wave: A Meteorological Retrospective|last=Borth|first=Samantha|date=|website=NOAA|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=9 February 2020}}</ref> |

In addition, the [[North Atlantic oscillation]] was in a strongly positive phase during the heat wave, which often foreshadows above average temperatures in the Eastern U.S. The Madden-Julian oscillation also entered a phase correlated with warm temperatures in the U.S. East.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.weather.gov/media/lot/events/March2012/March_Heatwave_2012_final.pdf|title=The Historic March 2012 Heat Wave: A Meteorological Retrospective|last=Borth|first=Samantha|date=|website=NOAA|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=9 February 2020}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:51, 10 December 2020

In March 2012, one of the greatest heat waves was observed in many regions of North America. Very warm air pushed northward west of the Great Lakes region, and subsequently spread eastward. The intense poleward air mass movement was propelled by an unusually intense low level southerly jet that stretched from Louisiana to western Wisconsin. Once this warm surge inundated the area, a remarkably prolonged period of record setting temperatures ensued.[1]

NOAA's National Climate Data Center reported that over 7,000 daily record high temperatures were tied or broken from 1 March through 27 March.[1] In some places the temperature exceeded 86 °F (30 °C). For instance, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the highest temperature recorded was 87 °F (31 °C) on March 21; in Chicago a high of 87 °F was also recorded on that same day. Records were broken in unusual ways. Chicago, for example, saw temperatures above 80 °F (27 °C) every day between March 14–18, breaking records on all five days. Chicago would go on to record eight days at or above 80 °F during the month, with many suburban areas recording an additional day in the 80s on March 19 (that day, the city only tied its record high of 78 °F (26 °C)). In context, the National Weather Service's Chicago branch noted that Chicago typically averages only one day in the 80's in April. And only once in 140 years of weather observations has April produced as many 80 °F days as this March.[2] In Traverse City, Michigan one day began with a low temperature (67 °F) that was higher than the previous record high for the day.

Temperature records across much of southern Canada also were shattered.[2] Some of the most impressive readings came from Nova Scotia on March 22, when the mercury climbed to 30.0 °C (86 °F) at a climate station in Lake Major,[3] making it the highest March temperature recorded in Nova Scotia, and the third highest March temperature recorded in Canada. That same day, the temperature hit 29.2 °C (84.6 °F) at Western Head, Nova Scotia.[4] The heat reached as far east as Cape Breton Island, with the temperature climbing to 24.0 °C (75.2 °F) at Sydney, Nova Scotia on March 22,[5] a place historically surrounded by ice-jammed waters, frigid winds, and snow in March. The week of March 18 also set record temperatures in Manitoba and much of Ontario [6] as well as into the Maritime Provinces.[7][8][9] Non-severe thunderstorms were reported on the evening hours of March 21, through to the early morning hours March 22 into northern Ontario.

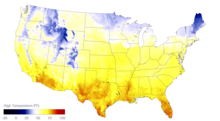

In addition, NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis data show that the atmospheric pattern was so persistent that much of the Midwest and Northeast, and up into Ontario, had temperature departures over periods of several days to a week or more of magnitudes which would be unusual even for a single day. Averaged over the seven-day period from March 16 to March 22 inclusive, nearly the entire area of the Midwest and Northeast U.S. and most of Ontario and Quebec had temperatures 18 °F (10 °C) or more above the 1981-2010 average. Even more dramatically, most of Iowa and Minnesota, all of Wisconsin and Michigan, and most of southeastern Ontario had seven-day mean temperatures more than 27 °F (15 °C) above the climatological average for the same period.[10][11][12][13][14][15]

An 84 °F (29 °C) high at Madison, Wisconsin in early March was 43 °F (24 °C) above average and followed an overnight low of 60 °F, 35 degrees above normal[16] the daily high being more than seven standard deviations above the mean. The absolute temperature and departure statistically would be equivalent to a mid-July high at that station in excess of 125 °F or more; the highest temperature recorded there was 107° at least once during the heat waves of the middle 1930s.[17]

This mild warm spell brought out spring peepers in northern Ontario on 23 March, which are usually not heard until mid-to-late April, or sometimes early May.

The warm weather was also responsible for several early-season tornado touchdowns, such as the EF3 that struck Dexter, Michigan, near Ann Arbor.[18][19]

Causes

A contributing factor to the unprecedented warmth was a warmer than average winter with below-average snowfall across the CONUS, meaning less thermal energy was required to heat the atmosphere.

It is no coincidence that this heat wave occurred immediately following "the biggest dose of heat we've received from a solar storm since 2005"[20][21] This came from a "flurry of eruptions on the sun...March 8th through 10th, the thermosphere absorbed 26 billion kWh of energy" Ironically, the scientist of the study speculated that CO, one of "the two most efficient coolants[not climate warmers] in the thermosphere, reradiated 95% of that total back into space" This phenomena repeated itself in the summer of 2012 with a series of M and X class flares resulting in another heat wave.

The primary,[22] immediate cause of the heat wave was a buckled jet stream caused by an abnormally strong high pressure ridge atop the Eastern United States and an unusually strong and slow-moving low pressure trough across the West, which brought with it below-average temperatures and snow. The tight pressure gradient allowed for an intense southerly jet to form, which transported warm, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico northward, with the moisture having an insulating effect during the night. The ridge also deflected storm systems northward away from the Eastern U.S. and kept skies clear, allowing further daytime radiative heating to occur.

In addition, the North Atlantic oscillation was in a strongly positive phase during the heat wave, which often foreshadows above average temperatures in the Eastern U.S. The Madden-Julian oscillation also entered a phase correlated with warm temperatures in the U.S. East.[23]

Continued warmth

On June 25, Denver, Colorado tied its all-time high with a temperature of 105 °F (41 °C). On the same day, at least two readings of 113 °F (45 °C) were recorded in Kansas. The heat was so strong that Alamosa, Colorado broke its daily record for six consecutive days. In Galveston, Texas, the earliest 100 °F (38 °C) day ever was recorded, on June 25.[24][25]

In northern Canada, Fort Good Hope, Northwest Territories had five consecutive days of 30 °C (86 °F) or higher, from June 21 to June 25, possibly the longest heat wave in Canada at that moment.[26]

On June 26, Hill City, Kansas was the warmest point in the United States with the thermometer climbing to 115 °F (46 °C).[27]

Thousands of records were being broken again on June 28. Fort Wayne, Indiana tied its all-time record high with 106 °F (41 °C) while Indianapolis broke its monthly record, at 104 °F (40 °C). More monthly records that day included St. Louis, Missouri at 108 °F (42 °C) and Little Rock, Arkansas at 107 °F (42 °C).[28][unreliable source?]

The scorching heat continued on June 29, when Washington, D.C. and Atlanta, Georgia recorded their highest June temperatures ever, at 104 °F (40 °C). Charlotte and Raleigh, North Carolina each tied their all-time records, at 104 °F (40 °C) and 105 °F (41 °C) respectively.[29]

The continued heat following the lack of snow the previous winter was a contributor to the record-shattering 2012 North American drought.

References

- ^ a b Meteorological March Madness 2012, Earth System Research Laboratory, 02 April 2012

- ^ a b "Historic Heat in North America Turns Winter to Summer". NASA Earth Observatory. NASA. 21 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Daily Data". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ^ "Daily Data". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ^ "Daily Data". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ^ Ontario Weather Review - Environment Canada - March 2012

- ^ 'Winter that wasn't' ends with Eastern heat wave', Calgary Herald, March 20, 2012

- ^ Summer-like weather smashing winter records, CTV News, March 19, 2012

- ^ Canada's Top Ten Weather Stories for 2012. 4. March’s Meteorological Mildness, Environment Canada, 2012

- ^ ESRL Web Team. "ESRL : PSD : Composite Daily Data Plot". Esrl.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ^ "Image provided by the NOAA/ESRL Physical Sciences Division, Boulder Colorado". Esrl.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ^ Kalnay, E. and Coauthors, 1996: The NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis 40-year Project. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 77, 437-471.

- ^ Amazing Stats from the March 2012 'Heat Wave', Accuweather, March 24, 2012

- ^ Toronto heat wave comes close to hottest March day on record, Toronto Star, March 22, 2012

- ^ Epic March heat wave in Midwest, Great Lakes and Northeast: link to global warming?, Washington Post, March 22, 2012

- ^ http://www.aos.wisc.edu/~sco/clim-history/stations/msn/msn-tts-2012.gif

- ^ analysis of raw data, file at:

- ^ Tornado slams Michigan homes, spares lives, CBS News, March 16, 2012

- ^ More than 100 homes damaged by Mich. tornado, USA Today, March 16, 2012

- ^ https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2012/22mar_saber/?fbclid=IwAR34u_W8r5_XyBEEZkRDo9_PGatR0zaDAa5eO7ZjxyFl98gKjt1_LSkx6x8

- ^ https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/news/saber-solarstorm.html?fbclid=IwAR17_RP7C-MDUDgsKHlqL_UOFaVSEfVAZ-sxsPknqYq1XunMpcsQb9gblMw

- ^ unsupported

- ^ Borth, Samantha. "The Historic March 2012 Heat Wave: A Meteorological Retrospective" (PDF). NOAA. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ http://www.srh.noaa.gov/hgx/?n=climate_gls_normals_jun

- ^ "All-Time Record Highs Fall in Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska". Accuweather.com. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ^ "Daily Data | Canada's National Climate Archive". Climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca. 2013-02-04. Archived from the original on 2012-12-16. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ^ "Hill City". Retrieved June 28, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "STORM2K • View topic - RECORD HIGHS JUNE 2012". Storm2k.org. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- ^ Samenow, Jason (2012-06-29). "Washington, D.C. shatters all-time June record high, sizzles to 104 - Capital Weather Gang". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2013-05-20.