Afrin Region: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Alter: title. | You can use this bot yourself. Report bugs here. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Wikipedia articles in need of updating from July 2019 | via #UCB_Category 496/549 |

restoring category |

||

| Line 363: | Line 363: | ||

[[Category:2014 establishments in Syria]] |

[[Category:2014 establishments in Syria]] |

||

[[Category:Aleppo Governorate]] |

[[Category:Aleppo Governorate]] |

||

[[Category:Afrin Region| ]] |

|||

Revision as of 14:13, 23 December 2020

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Afrin Region

Herêma Efrînê إقليم عفرين ܦܢܝܬܐ ܕܥܦܪܝܢ | |

|---|---|

One of seven de facto regions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria | |

|

| |

The seven regions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the Afrin region in orange | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aleppo |

| De facto Administration | Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria |

| Autonomy declared | January 29, 2014 |

| Administrative center |

|

| Government | |

| • Prime Minister | Hevi Ibrahim |

| Population | |

• Estimate (2018) | 323,000[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code | +963 21 |

Afrin Region (Template:Lang-ku, Template:Lang-ar, Template:Lang-syc) was the westernmost of the three original regions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria.

The region had two subordinate cantons, the Afrin Canton, consisting of the Afrin city area (with the Şêrewa, Mobata, Şêra and Maydankah districts subordinate to it), the Jindires area (with the Şiyê district subordinate to it), Rajo area (with the Bulbul, Maydana and Bahdina districts subordinate to it), as well as the Shahba Canton consisting of the Tell Rifaat area (with the Ahraz, Fafin and Kafr Naya districts subordinate to it).[5] The status of Manbij was unclear; while some reports described it as part of the Shabha Canton and Afrin Region, communal and regional elections weren't held there, and official documents that clarified the new regional framework didn't refer to Manbij.[6][7][8][9]

Afrin Region was first declared autonomous under the name of Afrin Canton in January 2014.[10][11] The subdivision of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria was renamed to Afrin Region during subdivision-congresses held in July and August 2017, while the name 'Afrin Canton' was then given to one of its two subdivisions as the canton or province became the name for second-level subdivisions in the Federation. Most of the Region's territory (including Afrin Canton) is under the Turkish occupation of northern Syria since early 2018. The last elected prime minister of Afrin Region was Hevi Ibrahim. The administrative centre of the region was the city of Afrin (now Tell Rifaat).[12]

Demographics

The western, mountainous part of Afrin Region area is overwhelmingly ethnic Kurdish, to the degree that this area has been described as "homogeneously Kurdish".[13] The central and eastern parts of Afrin region have a mixed ethnicity are ethnically highly diverse[14] population of area consists of Arab Syrians and Arabized Kurds found throughout the area, as well as a considerable Circassian and Chechen population in the city of Manbij and a considerable Syrian Turkmen and Arabized Turkmen population toward the north of this area. A smaller minority are Armenians. Toponymy and maps published by the French colonial authorities indicate that a significant percentage of inhabitants of this area who are officially classified as Arabs actually have Kurdish origins.[15]

Manbij and Tell Rifaat are the largest cities administered by de facto autonomous civil administrations operating under the umbrella of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. According to the 2004 Syrian census Manbij had 99,497[16] inhabitants, and Tell Rifaat 20,514[17]

History

The Afrin region area has seen human settlement since the early neolithic.[18][19]

According to René Dussaud, the region of Kurd-Dagh and the plain near Antioch were settled by Kurds since antiquity.[20][21] Stefan Sperl says that there is a reason to believe that Kurdish settlements in the Kurd Mountains go back to the Seleucid era, since those regions stood in the path to Antioch; Kurds in the early periods served as mercenaries and mounted archers.[22] In any case, the Kurd Mountains were already Kurdish-inhabited when the Crusades broke out at the end of the 11th century.[23]

In Classical Antiquity, the region was part of Chalybonitis (with its center at Chalybon or Aleppo), Chalcidice (with its center at Qinnasrīn العيس), and Cyrrhestica (with its center at Cyrrhus النبي حوري). This area was one of the most fertile and populated of the region. Under the Romans the region was made in 193 CE part of the province of Coele Syria or Magna Syria, which was ruled from Antioch. The province of Euphratensis was established in the 4th century CE in the east, its center was Hierapolis Bambyce (Manbij) which is still the main city of the region.

Under the Rashidun and Umayyad Muslim dynasties, the region was part of the Jund Qinnasrīn. In the Abbasid period the region was under the independent rule of the Hamdanids. The Mamluks and later the Ottomans governed the area until 1918. During the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922), the region was part of the Vilayet of Aleppo. The largest of the Kurdish-speaking tribal groups in northern Syria was the Reshwan confederation, which was initially based in Adıyaman Province but eventually also settled throughout Anatolia. The Milli confederation, mentioned in 1518 onward, was the most powerful group and dominated the entire northern Syrian steppe in the second half of the 18th century. The Kurdish dynasty of Janbulad ruled the region of Aleppo as Ottoman governors in 1591–1607.[24] At the beginning of the 17th century, districts of Jarabulus and Seruj on the left bank of the Euphrates had been settled by Kurds.[25]

During the French Mandate the region was part of the brief State of Aleppo. In modern post-independence Syria, the Kurdish society of the region was subject to heavy-handed Arabization policies by the Damascus government.[26]

In the course of the Syrian Civil War, Damascus government forces pulled back from the region in spring 2012 to give way to autonomous self-administration within the Rojava framework, which was formally declared on 29 January 2014, and the territory of Afrin Region virtually never saw civil war combat.[27] It was however at various times the target of artillery shelling by Islamist rebel groups[28] as well as by Turkey.[29][27][30] In response, Russian military troops reportedly stationed themselves in Afrin as part of an agreement to protect the YPG from further Turkish attacks.[31]

In early 2018 Afrin and surrounding areas were occupied by Turkish backed forces.[32][33] Since, the forces supported by Turkey have been accused of human rights violations by the human rights commissioner to the United Nations, Michelle Bachelet.[34]

Politics and administration

According to the Constitution of Rojava, Afrin Region's Legislative Assembly on its 29 January 2014 session declared autonomy.[35] The assembly elected Hêvî Îbrahîm Mustefa prime minister, who appointed Remzi Şêxmus and Ebdil Hemid Mistefa her deputies.

The remaining Executive Council was appointed as follows:[36]

| Name | Party | Office | Elected | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hêvî Îbrahîm Mustefa | PYD | Prime Minister | 2014 | ||

| Remzi Şêxmus | PYD | Deputy Prime Minister | 2014 | ||

| Ebdil Hemid Mistefa | PYD | Deputy Prime Minister | 2014 | ||

| Silêman Ceefer | N/A | Foreign Minister | 2014 | ||

| Ebdo Îbrahîm | PB-ASD | Defense Minister | 2014 | ||

| Hesen Beyrem | N/A | Interior Minister | 2014 | ||

| Nûrşan Hisên | PADKS | Regional Commissions, Councils and Planning Minister |

2014 | ||

| Remezan Elî | N/A | Finance Minister | 2014 | ||

| Erîfe Bekir | N/A | Labour and Social Security Minister | 2014 | ||

| Riyaz Menle Mehemed | N/A | Education Minister | 2014 | ||

| Eyûb Mihemed | N/A | Minister of Agriculture | 2014 | ||

| Xelîl Şêx Hesen | N/A | Health Minister | 2014 | ||

| Ehmed Yûsif | N/A | Economy and Trade Minister | 2014 | ||

| Riyaz Ebdilhenan Şêxo | N/A | Minister of Martyrs' Families | 2014 | ||

| Hêvîn Şêxo | N/A | Culture Minister | 2014 | ||

| Welîd Selame | N/A | Transport Minister | 2014 | ||

| Fazil Robcî | N/A | Youth and Sports Minister | 2014 | ||

| Reşîd Ehmed | N/A | History and Tourism Minister | 2014 | ||

| Mihemed Hemîd Qasim | N/A | Religious Affairs Minister | 2014 | ||

| Fatme Lekto | N/A | Women and Family Minister | 2014 | ||

| Xelîl Sîno | N/A | Human Rights Minister | 2014 | ||

| Etûf Ebdo | N/A | Supervision Minister | 2014 | ||

| Ebdil Rehman Selman | N/A | Information Minister | 2014 | ||

| Seîd Esmet Xûbarî | N/A | Justice Minister | 2014 | ||

| Kamîran Ehmed Şefîi Bilal | N/A | Energy Minister | 2014 | ||

Economy

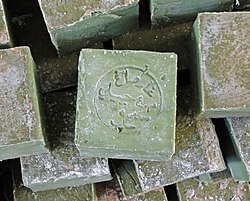

Afrin is well known for its olive groves.[37] The areas governed by the SDC are under a blockade imposed by neighbouring Turkey,[38][better source needed] which places high burdens on international import and export. For example, transportation of Aleppo soap to international markets, as far as possible at all, has at least four times the transportation cost as compared to pre-war years.[39] In 2015 there were 32 tons of Aleppo soap produced and exported to other parts of Syria, but also to international markets.[40]

Education

Like in the other Rojava regions, primary education in the public schools is initially by mother tongue instruction either Kurdish or Arabic, with the aim of bilingualism in Kurdish and Arabic in secondary schooling.[41][42] Curricula are a topic of continuous debate between the regions' Boards of Education and the Syrian central government in Damascus, which partly pays the teachers.[43][44][45][46]

The federal, regional and local administrations in Rojava put much emphasis on promoting libraries and educational centers, to facilitate learning and social and artistic activities.[47]

Afrin Region has institution of higher education. Most notably the University of Afrin, founded in 2015. After teaching three programs (Electromechanical Engineering, Kurdish Literature and Economy) in the first academic year, the second academic year with an increased 22 professors and 250 students has three additional programs (Human Medicine, Journalism and Agricultural Engineering).[48]

See also

- Federalization of Syria

- Rojava conflict

- Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

- Jazira Region

- Euphrates Region

References

- ^ Abboud 2018, Table 4.1 Cantons of the Rojava Administration.

- ^ Walid Al Nofal; Tariq Adely (12 March 2018). "Turkish-backed rebels poised to encircle Afrin city after days of swift advances". Syria Direct. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Afrin Canton Executive Council: We promise to return home". ANF. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "UN 'alarmed' over children casualties in Afrin".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-09-20. Retrieved 2017-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Rojava authorities. "Announce elections". Rudaw.

- ^ Muslim, Salim. "Only way to keep Syria united by the adoption of a decentralised, democratic and secular system". vrede.be. Vrede vzw. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ Iddon, Paul (10 September 2017). "The power plays behind Russia's deconfliction in Afrin". Rudaw. Rudaw. Rudaw. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Kurdish force may leave Raqqa campaign if Turkey continues attacks". Rudaw. Rudaw. Rudaw. 28 July 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Democratic autonomy has declared in Afrin canton in Rojava". Mednuce. 29 January 2014. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "After Cizîre, Kobanê Canton has been declared". Firat News. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Rojava Cantons; Personal Website of Mutlu Civiroglu". civiroglu.net. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Rojava's Sustainability and the PKK's Regional Strategy". Washington Institute. 2 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ "Syria: Ethnic Composition". Gulf/2000 Project. Columbia University. 1997–2016. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- ^ Balanche, Fabrice (2016-08-24). "Rojava's Sustainability and the YPG's Regional Strategy". The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ General Census of Population and Housing 2004 Archived 2012-07-29 at archive.today. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Aleppo Governorate.(in Arabic)

- ^ General Census of Population and Housing 2004 Archived 2015-12-08 at the Wayback Machine. Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Aleppo Governorate.(in Arabic)

- ^ Besançon, J.; Sanlaville, P. (1981), "Aperçu géomorpholoqique sur la vallée de l' Euphrate syrien", Paléorient (in French), 7 (2): 5–18 (14), doi:10.3406/paleo.1981.4295

- ^ Muhesen, Sultan (2002), "The Earliest Paleolithic Occupation in Syria", in Akazawa, Takeru; Aoki, Kenichi; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (eds.), Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia, New York: Kluwer, pp. 95–105 (102), doi:10.1007/0-306-47153-1_7, ISBN 0-306-47153-1

- ^ Dussaud, René (1927). Topographie historique de la Syrie antique et médiévale. Geuthner. p. 425.

- ^ Chaliand, Gérard (1993). A People Without a Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan. Zed Books. p. 196. ISBN 9781856491945.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, P.G.; Sperl, S. (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 0415072654.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, P.G.; Sperl, S. (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. pp. 114. ISBN 0415072654.

- ^ Salibi, Kamal S. (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780520071964.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 9781134096435.

- ^ "SYRIA: The Silenced Kurds; Vol. 8, No. 4(E)". Human Rights Watch. 1996.

- ^ a b Thomas Schmidinger (24 February 2016). "Afrin and the Race for the Azaz Corridor". Newsdeeply. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "Nusra militants shell Kurdish areas in Syria's Afrin, Kurds respond". ARA News. 30 August 2015. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "Turkish forces shell Afrin countryside, killing and injuring about 16 most of them from the self-defense forces and Asayish". SOHR. 9 July 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "Turkey strikes Kurdish city of Afrin northern Syria, civilian casualties reported". ARA News. 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- ^ "US and Russian military units patrol Kurdish-controlled areas in northern Syria". Al-Masdar. May 1, 2017.

- ^ "Military occupation of Syria by Turkey | Rulac". www.rulac.org. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ "Human rights situations that require the Council's attention". United Nations. 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "OHCHR | Syria: Violations and abuses rife in areas under Turkish-affiliated armed groups – Bachelet". www.ohchr.org. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds celebrate Auto Administration". Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ "ÇİFTE DEVRİM - Gerçekler karanlıkta kalmayacak - Özgür Gündem". 30 January 2014.

- ^ "Ahval | Spotlight on Turkey: Facts and Views". Ahval. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- ^ "Rojava'dan ikazlar". Cumhuriyet.

- ^ "Bio-Seife aus dem Kriegsgebiet". Der Spiegel. 13 February 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ "Will Syria's Kurds succeed at self-sufficiency?". Al-Monitor. 3 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- ^ "Education in Rojava after the revolution". ANF. 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ^ "After 52-year ban, Syrian Kurds now taught Kurdish in schools". Al-Monitor. 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Hassakeh: Syriac Language to Be Taught in PYD-controlled Schools". The Syrian Observer. 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ^ "Kurds introduce own curriculum at schools of Rojava". Ara News. 2015-10-02. Archived from the original on 2017-06-06. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Revolutionary Education in Rojava". New Compass. 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ "Education in Rojava: Academy and Pluralistic versus University and Monisma". Kurdishquestion. 2014-01-12. Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Kurds establish university in Rojava amid Syrian instability". Kurdistan24. 2016-07-07. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- ^ "Afrin University is opened today". Hawar News Agency. 9 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-10-18. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

Works cited

- Abboud, Samer N. (2018). Syria: Hot Spots in Global Politics. Cambridge: Polity (publisher). ISBN 978-1-509-52241-5.

External links

- Map of majority ethnicities in Syria by Gulf2000 project of Columbia university