Technological singularity: Difference between revisions

Jason Hommel (talk | contribs) |

Jason Hommel (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

== Wikipedia == |

== Wikipedia == |

||

Wikipedia itself may be thought of as a form of AI that is growing exponentially, organically, and increasing its knowledge base. It is not exactly growing by itself, but rather, by the input of many people. The knowledge base is organized, cross referenced, and includes a standard set of rules, and is far beyond the knowledge of one man, or even a group of men, and is clearly more in depth and more up to date than any prior published encyclopedia ever before developed. |

Wikipedia itself may be thought of as a form of AI that is growing exponentially <ref>http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Modelling_Wikipedia%27s_growth</ref>, organically, and increasing its knowledge base. It is not exactly growing by itself, but rather, by the input of many people. The knowledge base is organized, cross referenced, and includes a standard set of rules, and is far beyond the knowledge of one man, or even a group of men, and is clearly more in depth and more up to date than any prior published encyclopedia ever before developed. |

||

In the movie, Terminator III, the AI was the network itself that became "self aware". |

In the movie, Terminator III, the AI was the network itself that became "self aware". |

||

Revision as of 18:58, 14 January 2007

In futures studies, a technological singularity (often the Singularity) is a predicted future event believed to precede immense technological progress in an unprecedentedly brief time. Futurologists give varying predictions as to the extent of this progress, the speed at which it occurs, and the exact cause and nature of the event itself.

One school of thought centers around the writings of Vernor Vinge, in which he examines what I. J. Good (1965) described earlier as an “intelligence explosion.” Good predicts that if artificial intelligence reaches equivalence to human intelligence, it will soon become capable of augmenting its own intelligence with increasing effectiveness, far surpassing human intellect. In the 1980s, Vernor Vinge dubbed this event “the Singularity” and popularized the idea with lectures, essays, and science fiction. Vinge argues the Singularity will occur following creation of strong AI or sufficiently advanced intelligence amplification technologies such as brain-computer interfaces.

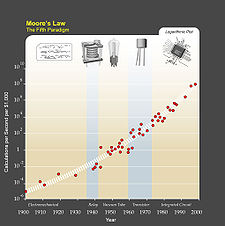

Another school, promoted heavily by Ray Kurzweil, claims that technological progress follows a pattern of exponential growth, suggesting rapid technological change in the 21st century and the singularity occurring in 2045. Kurzweil considers the advent of superhuman intelligence to be part of an overall exponential trend in human technological development seen originally in Moore’s Law and extrapolated into a general trend in Kurzweil’s own Law of Accelerating Returns.

While some regard the Singularity as a positive event and work to hasten its arrival, others view it as dangerous or undesirable. The most practical means for initiating the Singularity are debated, as are how (or whether) it can be influenced or avoided if dangerous.

The Singularity is also frequently depicted in science fiction.

Intelligence explosion

I. J. Good (1965) writes:

- “Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.”

Mathematician and author Vernor Vinge greatly popularized Good’s notion of an intelligence explosion in the 1980s, calling it the Singularity. Vinge first addressed the topic in print in the January 1983 issue of Omni magazine. He later collected his thoughts in the 1993 essay “The Coming Technological Singularity,” which contains the oft-quoted statement “Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly thereafter, the human era will be ended.”

Vinge writes that superhuman intelligences, however created, will be even more able to enhance their own minds faster than the humans that created them. “When greater-than-human intelligence drives progress,” Vinge writes, “that progress will be much more rapid.” This feedback loop of self-improving intelligence, he predicts, will cause large amounts of technological progress within a short period of time.

Most proposed methods for creating smarter-than-human or transhuman minds fall into one of two categories: intelligence amplification of human brains and artificial intelligence. The means speculated to produce intelligence augmentation are numerous, and include bio- and genetic engineering, nootropic drugs, AI assistants, direct brain-computer interfaces, and mind transfer. Despite the numerous speculated means for amplifying human intelligence, non-human artificial intelligence (specifically seed AI) is the most popular option for organizations trying to directly initiate the Singularity, a choice the Singularity Institute addresses in its publication “Why Artificial Intelligence?” (2005).[2] Robin Hanson is also skeptical of human intelligence augmentation, writing that once one has exhausted the “low-hanging fruit” of easy methods for increasing human intelligence, further improvements will become increasingly difficult to find.[3]

Potential dangers

Some speculate superhuman intelligences may have goals inconsistent with human survival and prosperity. AI researcher Hugo de Garis suggests AIs may simply eliminate the human race, and humans would be powerless to stop them—an outcome that he himself argues humans could not resist. Other oft-cited dangers include molecular nanotechnology and genetic engineering. These threats are major issues for both Singularity advocates and critics, and were the subject of a Wired magazine article by Bill Joy, Why the future doesn’t need us (2000).

In an essay on human extinction scenarios, Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom (2002) lists superintelligence as a possible cause:

- “When we create the first superintelligent entity, we might make a mistake and give it goals that lead it to annihilate humankind, assuming its enormous intellectual advantage gives it the power to do so. For example, we could mistakenly elevate a subgoal to the status of a supergoal. We tell it to solve a mathematical problem, and it complies by turning all the matter in the solar system into a giant calculating device, in the process killing the person who asked the question.”

Many Singularitarians consider nanotechnology to be one of the greatest dangers facing humanity. For this reason, they often believe seed AI should precede nanotechnology. Others, such as the Foresight Institute, advocate efforts to create molecular nanotechnology, claiming nanotechnology can be made safe for pre-Singularity use or can expedite the arrival of a beneficial Singularity.

Advocates of friendly artificial intelligence acknowledge the Singularity is potentially very dangerous and work to make it safer by creating AI that will act benevolently towards humans and eliminate existential risks. AI researcher Bill Hibbard also addresses issues of AI safety and morality in his book Super-Intelligent Machines. Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics are one of the earliest examples of proposed safety measures for AI. The laws are intended to prevent artificially intelligent robots from harming humans, though the crux of Asimov’s stories is often how the laws fail. In 2004, the Singularity Institute launched an internet campaign called 3 Laws Unsafe to raise awareness of AI safety issues and the inadequacy of Asimov’s laws in particular.

Accelerating change

Some proponents of the Singularity argue its inevitability through extrapolation of past trends, especially those pertaining to shortening gaps between improvements to technology. In one of the first uses of the term singularity in the context of technological progress, Stanislaw Ulam cites accelerating change:

- “One conversation centered on the ever accelerating progress of technology and changes in the mode of human life, which gives the appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race beyond which human affairs, as we know them, could not continue.” —May 1958, referring to a conversation with John von Neumann

In Mindsteps to the Cosmos (HarperCollins, August 1983), Gerald S. Hawkins explains his notion of mindsteps, dramatic and irreversible changes to paradigms or world views. He cites the inventions of writing, mathematics, and the computer as examples of such changes. He writes that the frequency of these events is accelerating, which he quantifies in his mindstep equation.

Since the late 1970s, others like Alvin Toffler (author of Future Shock), Daniel Bell and John Naisbitt have approached the theories of postindustrial societies similar to visions of near- and post-Singularity societies. They argue the industrial era is coming to an end, and services and information are supplanting industry and goods. Some more extreme visions of the postindustrial society, especially in fiction, envision the elimination of economic scarcity.

Ray Kurzweil justifies his belief in an imminent singularity by an analysis of history from which he concludes that technological progress follows a pattern of exponential growth. He calls this conclusion The Law of Accelerating Returns. He generalizes Moore's law, which describes exponential growth in integrated semiconductor complexity, to include technologies from far before the integrated circuit.

Whenever technology approaches a barrier, Kurzweil writes, new technologies will cross it. He predicts paradigm shifts will become increasingly common, leading to “technological change so rapid and profound it represents a rupture in the fabric of human history” (Kurzweil 2001). Kurzweil believes the Singularity will occur before the end of the 21st century, setting the date at 2045 (Kurzweil 2005). His predictions differ from Vinge’s in that he predicts a gradual ascent to the Singularity, rather than Vinge’s rapidly self-improving superhuman intelligence. The distinction is often made with the terms soft and hard takeoff.

Criticism

Theodore Modis and Jonathan Huebner have argued, from different perspectives, that the rate of technological innovation has not only ceased to rise, but is actually now declining. Others propose that other “singularities” can be found through analysis of trends in world population, world GDP, and other indices. Andrey Korotayev and others argue that historical hyperbolic growth curves can be attributed to feedback loops that ceased to affect global trends in the 1970s, and thus hyperbolic growth should not be expected in the future.

William Nordhaus in the empiricial study The Progress of Computing shows how the rapid performance trajectory of modern computing began only around 1940. Before that, performance growth followed the much slower performance trajectories of a traditional industrial economy. Hence, Nordhaus rejects Kurzweil’s claims that Moore’s Law can be extrapolated back into the 19th century and the Babbage Computer.

Schmidhuber (2006) suggests perceptions of accelerating change only reflect differences in how well individuals and societies remember recent events as opposed to more distant ones. He claims such phenomena may be responsible for apocalyptic predictions throughout history.

Some anti-civilization theorists, such as John Zerzan and Derrick Jensen, represent the school of anarcho-primitivism or eco-anarchism, which sees the rise of the technological singularity as an orgy of machine control, and a loss of a feral, wild, and uncompromisingly free existence outside of the factory of domestication (civilization). In essence, environmental groups such as the Earth Liberation Front and Earth First! see the singularity as a force to be resisted at all costs. Author and social change strategist James John Bell has written articles for Earth First! as well as mainstream science and technology publications, like The Futurist, providing a cautionary environmentalist perspective on the singularity, including his essays Exploring The “Singularity” and Technotopia and the Death of Nature: Clones, Supercomputers, and Robots. Also, the publication Green Anarchy, to which Ted Kaczynski and Zerzan are regular contributors, has published articles about resistance to the technological singularity, e.g. A Singular Rapture, written by MOSH (which is in reference to Kurzweil’s M.O.S.H., for “Mostly Original Substrate Human”).

Just as Luddites opposed artifacts of the industrial revolution, due to concern for their effects on employment, some opponents of the Singularity are concerned about future employment opportunities. Although Luddite fears about jobs were not realised, given the growth in jobs after the industrial revolution, there was an effect on involuntary employment: a dramatic decrease in child labor and the labors of the overaged. It can be argued that only a drop in voluntary employment should be of concern, not a reduced level of absolute employment (such a position is held by Henry Hazlitt).

Popular culture

In addition to the Vernor Vinge stories that pioneered Singularity ideas, several other science fiction authors have written stories that involve the Singularity as a central theme. Notable authors include William Gibson, Charles Stross, Karl Schroeder, Greg Egan, David Brin, Iain M. Banks, Neal Stephenson, Bruce Sterling, Damien Broderick, Fredric Brown, Jacek Dukaj, Nagaru Tanigawa and Cory Doctrow. Ken MacLeod describes the Singularity as “the Rapture for nerds” in his 1998 novel The Cassini Division. Singularity themes are common in cyberpunk novels, such as the recursively self-improving AI Wintermute in William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer. A 1994 novel published on Kuro5hin called The Metamorphosis of Prime Intellect depicts life after an AI-initiated Singularity. A more dystopian version is Harlan Ellison’s short story I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream. Yet more examples are Accelerando by Charles Stross, and Warren Ellis’ ongoing comic book series newuniversal. Puppets All by James F. Milne explores the emotional and moral problems approaching Singularity.

Popular movies that include the Singularity idea as computers that develop an artificial intelligence and become malicious include: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Superman III, Terminator, Terminator II and III, I Robot, Artificial Intelligence AI, and many others.

Isaac Asimov expressed ideas similar to a post-Kurzweilian Singularity in his short story The Last Question. Asimov's future envisions a reality where a combination of strong artificial intelligence and post-humans consume the cosmos, during a time Kurzweil describes as when "the universe wakes up", the last of his six stages of cosmic evolution as described in The Singularity is Near. Post-human entities throughout various time periods of the story enquire of the artificial intelligence within the story as to how entropy death will be avoided. The AI responds that it lacks sufficient information to come to a conclusion, until the end of the story when the AI realizes that the solution is to re-create the universe from scratch, suggesting a possible outcome of Kurzweil's six-stage cosmological evolution is that the six stages occur in an endless, repeating cycle.

St. Edward’s University chemist Eamonn Healy provides his own take on the Singularity concept in the film Waking Life. He describes the acceleration of evolution by breaking it down into “two billion years for life, six million years for the hominid, a hundred-thousand years for mankind as we know it” then describes the acceleration of human cultural evolution as being ten thousand years for agriculture, four hundred years for the scientific revolution, and one hundred fifty years for the industrial revolution. He concludes we will eventually create “neohumans” which will usurp humanity’s present role in scientific and technological progress and allow the exponential trend of accelerating change to continue past the limits of human ability.

In his book The Artilect War, Hugo de Garis predicts a coming conflict between supporters of the creation of artificial intellects (or artilects), whom he refers to as "cosmists", and those who oppose the idea, who he refers to as "terrans". De Garis envisions a coming battle between these groups over the creation of artilects as being the last great struggle mankind will face before the Singularity.

Organizations and other prominent voices

The Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research institute for the study and advancement of beneficial AI that is working to shape what statistician I.J. Good called the “intelligence explosion.” It has the additional goal of fostering a broader discussion and understanding of Friendly Artificial Intelligence. It focuses on Friendly AI, as it believes strong AI will enhance cognition before human cognition can be enhanced by neurotechnologies or somatic gene therapy. The Institute employs Tyler Emerson as executive director, Allison Taguchi as director of development, AI researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky as a research fellow, Marcello Herreshoff as a research associate, and Michael Wilson as a research associate. Acceleration Studies Foundation (ASF), an educational nonprofit, was formed to attract broad scientific, technological, business, and social change. The interest in acceleration and evolutionary development studies. It produces Accelerating Change, an annual conference on multidisciplinary insights in accelerating technological change, held at Stanford University, and maintains Acceleration Watch [4], an educational site discussing accelerating technological change.

Other prominent voices:

- Marvin Minsky is an American scientist in the field of artificial intelligence (AI), co-founder of MIT’s AI laboratory, and author of several texts on AI and philosophy.

- Hans Moravec is a permanent resident research professor at the Robotics Institute of Carnegie Mellon University known for his work on robotics, artificial intelligence, and writings on the impact of technology.

- Max More, formerly known as Max T. O’Connor, is a philosopher and futurist who writes, speaks, and consults on advanced decision making and foresight methods for handling the impact of emerging technologies.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia itself may be thought of as a form of AI that is growing exponentially [1], organically, and increasing its knowledge base. It is not exactly growing by itself, but rather, by the input of many people. The knowledge base is organized, cross referenced, and includes a standard set of rules, and is far beyond the knowledge of one man, or even a group of men, and is clearly more in depth and more up to date than any prior published encyclopedia ever before developed.

In the movie, Terminator III, the AI was the network itself that became "self aware".

Notes

See also

- Clarke’s three laws

- Doomsday argument

- End of civilization

- Indefinite lifespan

- Logarithmic timeline, and Detailed logarithmic timeline

- Omega point

- Outside Context Problem

- Lifeboat Foundation

- Simulated reality

- Technological evolution

- Techno-utopianism

- Tipping point

- Transhumanism

- Fermi’s Paradox

- Molecular engineering

- Genetic modification

References

- Broderick, D. (2001). The Spike: How Our Lives Are Being Transformed by Rapidly Advancing Technologies. New York: Forge. ISBN 0-312-87781-1.

- Bostrom, N. (2002). "Existential Risks". Journal of Evolution and Technology. 9.

- Bostrom, N. (2003). "Ethical Issues in Advanced Artificial Intelligence". Cognitive, Emotive and Ethical Aspects of Decision Making in Humans and in Artificial Intelligence. 2: 12–17.

- Good, I. J. (1965). “Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine,” in Advances in Computers, vol 6, Franz L. Alt and Morris Rubinoff, eds, pp31-88, 1965, Academic Press.

- Joy, B. (April 2000). "Why the future doesn't need us". Wired Magazine. 8.04.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Kurzweil, R. (2001). "The Law of Accelerating Returns".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kurzweil, R. (2005). The Singularity is Near. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-03384-7.

- Schmidhuber, J. (2006). "New Millennium AI and the Convergence of History".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Inc. (2005). "Why Artificial Intelligence?". Retrieved February 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Ulam, S. (1958). “Tribute to John von Neumann,” Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, vol 64, nr 3, part 2, May 1958, pp1-49.

- Vinge, V. (1993). "The Coming Technological Singularity".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

Essays

- Singularities and Nightmares: Extremes of Optimism and Pessimism About the Human Future by David Brin

- “Meaning of Life FAQ” by Eliezer Yudkowsky

- A Critical Discussion of Vinge’s Singularity Concept

- Is a singularity just around the corner? by Robin Hanson

- Brief History of Intellectual Discussion of Accelerating Change by John Smart

- Encouraging a Positive Transcension

- Michael Anissimov’s Singularity articles

- One Half of a Manifesto by Jaron Lanier—a critique of “cybernetic totalism”

- One Half of an Argument—Kurzweil’s response to Lanier

- A Singular Rapture

- The Singularity is Nonsense by Tim Tyler, criticizing the use of the term singularity to describe this phenomenon

- Singularity of AI by Paul “nEo” Martin

Singularity AI projects

- The Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence

- The SSEC Machine Intelligence Project

- The Artificial General Intelligence Research Institute

Portals and wikis

- KurzweilAI.net

- Acceleration Watch

- Accelerating Future

- The SL4 Wiki

- Accelerating Technology

- Singularity! A Tough Guide to the Rapture of the Nerds

Fiction

- The Metamorphosis of Prime Intellect—A 1994 novel by Roger Williams. It deals with the ramifications of a superpowerful computer that can alter reality after a technological singularity.

Other links

Template:Energy Development and Use Template:Sustainability and energy development group