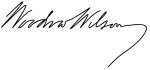

Woodrow Wilson and race: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit |

||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

Wilson purportedly lamented the contamination of American bloodlines by the "sordid and hapless elements" coming from southern and eastern Europe.<ref>{{Cite journal|author-link=Stephen Skowronek|first=Stephen|last=Skowronek|year=2006|page=389|volume=100|issue=3|title=The Reassociation of Ideas and Purposes: Racism, Liberalism, and the American Political Tradition|journal=[[American Political Science Review]]<!--|pages=385-401-->|doi=10.1017/S0003055406062253|s2cid=17516798}}</ref> |

Wilson purportedly lamented the contamination of American bloodlines by the "sordid and hapless elements" coming from southern and eastern Europe.<ref>{{Cite journal|author-link=Stephen Skowronek|first=Stephen|last=Skowronek|year=2006|page=389|volume=100|issue=3|title=The Reassociation of Ideas and Purposes: Racism, Liberalism, and the American Political Tradition|journal=[[American Political Science Review]]<!--|pages=385-401-->|doi=10.1017/S0003055406062253|s2cid=17516798}}</ref> |

||

Despite claims he harbored anti-Semitic prejudices, Wilson appointed the first Jewish-American to the Surpeme Court, [[Louis Brandeis]]. Wilson did so knowing as both a Jew and staunch progressive, Brandeis would be a divisive nominee who’d face an uphill confirmation. Brandeis vividly contrasted with Wilson’s first appointment, the openly bigoted[[James Clark McReynolds| James McReynolds]], who prior to joining the court had served as Wilson’s first Attorney General. On a personal level, McReynold’s was widely seen by his peers and as a mean spirited bigot, whose disrespect was so extreme he’d turn his chair around to face the wall whenever African-American attorneys addressed the court for oral arguments.<ref>"James C. McReynolds". Oyez Project Official Supreme Court media. Chicago Kent College of Law. Retrieved March 20, 2012</ref> An unapologetic anti-Semite as well, McReynolds refused to sign opinions by any of his Jewish colleagues on the court. |

Despite claims he harbored anti-Semitic prejudices, Wilson appointed the first Jewish-American to the Surpeme Court, [[Louis Brandeis]]. Wilson did so knowing as both a Jew and staunch progressive, Brandeis would be a divisive nominee who’d face an uphill confirmation. Brandeis vividly contrasted with Wilson’s first appointment, the openly bigoted[[James Clark McReynolds| James McReynolds]], who prior to joining the court had served as Wilson’s first Attorney General. On a personal level, McReynold’s was widely seen by his peers and as a mean spirited bigot, whose disrespect was so extreme he’d turn his chair around to face the wall whenever African-American attorneys addressed the court for oral arguments.<ref>"James C. McReynolds". Oyez Project Official Supreme Court media. Chicago Kent College of Law. Retrieved March 20, 2012</ref> An unapologetic anti-Semite as well, McReynolds refused to sign opinions by any of his Jewish colleagues on the court. |

||

It should be noted, though Wilson appointed easily the most overtly intolerant Judge in modern times (if not ever) in the form of McReynolds; his legacy to the Supreme Court was overall much more favorable towards racial equality than not. While Brandeis and McReynolds were appointees who cancelled each other out ideologically, Wilson’s third appointment to the bench, [[John Hessin Clarke]], was a progressive who aligned himself closely with Brandeis and the Court’s liberal wing. This point also requires context however; whereas Brandeis and McReynolds served until 1939 and 1941 respectively, Clarke resigned from his lifetime appointment in 1922, after barely 5 years on the bench. Among his reasons for quitting, Clarke cited bullying from McReynolds as at least partial motivation. Ultimately McReynolds sat on the Supreme Court longer than any other Wilson nominee, being both the first and last Wilson nominee on the court. Unlike his other prominent racist appointments, Wilson purportedly expressed remorse over McReynolds, allegedly calling it his "greatest regret."<ref>Berg, 400</ref> |

|||

== Assessment and legacy == |

== Assessment and legacy == |

||

Revision as of 01:59, 20 February 2021

Woodrow Wilson was a prominent American scholar and politician who served as the 28th President of the United States from 1913-1921. While Wilson's tenure is often noted for being one of progressive achievement, his time in office was seen by scholars as one of unprecedented regression with concern to racial equality. [1]

Several historians have spotlighted examples in the public record of Wilson's racist policies and political appointments, such as segregationists he placed in his Cabinet.[2][3][4] Other sources claim Wilson defended segregation on ”scientific“ grounds in private and describe him as a man who “loved to tell racist 'darky' jokes about black Americans.”[5][6]

Family and Early Life

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was born and raised in the American South by parents who were supporters of the Confederacy. His father, Joseph Wilson, supported slavery and served as a chaplain with the Confederate army.[7] Wilson's father was one of the founders of the Southern Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) after it split from the Northern Presbyterians in 1861 over the issue of succession. Joseph became minister of the First Presbyterian Church in Augusta, and the family lived there until 1870.[8]

While it is unclear whether the Wilsons ever owned slaves the Presbyterian Church, as compensation for his father services as a pastor, provided slaves who attended to the Wilson family. Wilson claimed that his earliest memory was of playing in his front yard as a three year old and hearing a passerby announce with disgust that Abraham Lincoln had been elected and that a war was coming.[9][10]

One of only two Democrats elected to the presidency between 1860-1932 and the first southerner[11] to be elected president since Zachary Taylor in 1848, Wilson was the only former subject of the Confederacy to serve as President. Wilson's election was celebrated by southern segregationists.[12]

Wilson's views as an academic

Wilson was an apologist for slavery and the southern redemption movement; he was also one of the nation’s foremost promoters of lost cause mythology.[13] At Princeton, Wilson used his authority to actively dissuade the admission of African-Americans.[14]

Prior to entering politics, Wilson was one of the most highly regarded academics in America. Wilson’s published works and area of scholarship focused on American history. Though this fact received less attention both during and after Wilson’s academic career, much of his writings are overtly sympathetic towards both slavery, the confederacy and redeemer movement. One of Wilson's books, History of the American People, includes such observations and was used as source material for Birth of a Nation, a film that portrayed the Ku Klux Klan as a benevolent force.[15]: 518–519 Quotes from Wilson's History of the American People used for the move include:

"Adventurers swarmed out of the North, as much the enemies of one race as of the other, to cozen, beguile and use the negroes.... [Ellipsis in the original.] In the villages the negroes were the office holders, men who knew none of the uses of authority, except its insolences."

"....The policy of the congressional leaders wrought…a veritable overthrow of civilization in the South.....in their determination to 'put the white South under the heel of the black South.'" [Ellipses and underscore in the original.]

"The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation.....until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the southern country." [Ellipsis in the original.]

However, Wilson had harsh words about the gap between the original goals of the KKK and what it evolved into.[16]

Congressional Government, another highly regarded civic publication of Wilson's, includes a strong condemnation of Reconstruction Era policies. Wilson refers to the time period as being characterized of "Congressional Despotism", a time when both states rights and the system of checks and balances disregarded. Wilson specifically criticizes efforts to protect voting rights for African-Americans and ruling by federal judges against state courts that refused to empanel black jurors. According to Wilson, congressional leaders had acted out of idealism, displaying "blatant disregard of the child-like state of the Negro and natural order of life", thus endangering American democracy as a whole.[17]

President of Princeton

In 1902, the board of trustees for Princeton University, selected Wilson to be the school's next President.[18] Wilson appointed the first Jew and the first Roman Catholic to the faculty, and helped liberate the board from domination by conservative Presbyterians.[19] Despite these reforms and being generally viewed as a success in his administrative role role, Wilson used his position at Princeton to exclude African-Americans from attendance.[20] At the time, opportunities for higher education were limited for African-Americans; though a handful of mostly elite, Northern schools did admit black students, few colleges and universities accepted black students prior to the twentieth century. Most African-Americans who were able to attend college studied at HBCUs such as Howard University, but by the early 1900s, virtually all Ivy League schools had begun admitting small numbers of black students.[21][22]

Exclusion of African-Americans from administration appointments

By the 1910s, African-Americans had become effectively shut out of elected office. Obtaining an executive appointment to a position within the federal bureaucracy was usually the only option for African-American statesmen. It has been claimed Wilson continued to appoint African-Americans to positions that had traditionally been filled by blacks, overcoming opposition from many southern senators.[23] Such claims deflect most of the truth however. Since the end of Reconstruction, both parties recognized certain appointments as unofficially reserved for qualified African-Americans. Wilson appointed a total of nine African-Americans to prominent positions in the federal bureaucracy, eight of whom were Republican carry-overs. For comparison, President Taft was met with disdain and outrage from both white Republicans and African-American leaders for appointing "a mere thirty-one black officeholders", a record low for a Republican. Upon taking office, Wilson fired all but two of the seventeen black supervisors in the federal bureaucracy appointed by Taft. Wilson flatly refused to even consider African-Americans for appointments in the South. Since 1863, the U.S. mission to Haiti and Santo Domingo was almost always led by an African-American diplomat regardless of what party the sitting President belonged to; Wilson ended this half century old tradition, though he did continue appointing black diplomats to head the U.S. mission to Liberia.[24][25]

Segregating the federal bureaucracy

Since the end of Reconstruction, the federal bureaucracy had been possibly the only career path where African-Americans “witnessed some level of equity”[26] and was the life blood and foundation of the black middle-class.[27][28] Though Wilson's administration dramatically escalated discriminatory hiring policies and the level of segregation of federal government offices; both of these practice pre-dated his administration and reached notable levels for the first time since Reconstruction beginning under President Theodore Roosevelt; a regression that continued under President William Howard Taft.[29] While This trend has been pointed to by Wilson apologists such as Berg, the discrepancy between these three administrations is extreme.[30] For example, African-American federal clerks earning top pay, were twelve times more likely to be promoted (48) then demoted (4) over the course of the Taft administration; in contrast, the same class of black workers were twice as likely to be demoted or fired (22) than promoted (11) during Wilson's first term in office.[31] Further, prominent African-American activists including W.E.B. DuBois described the federal bureaucracy as being effectively devoid of significant racist discrimination prior to Wilson.[32]

Not only were African-Americans almost completely excluded from higher level appointments, Wilson cabinet was dominated by southerners, many of whom were unapologetic white supremacists.[33] In Wilson's first month in office, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson, a former Democratic congressman from Texas, urged the president to establish segregated government offices.[34] Wilson did not adopt Burleson's proposal, but he did resolve to give his Cabinet Secretaries discretion to segregate their respective departments.[35] By the end of 1913, many departments, including the Navy, Treasury, Commerce and UPS, had segregated work spaces, restrooms, and cafeterias.[34] Many agencies used segregation as a pretext to adopt whites-only employment policies on the basis that they lacked facilities for black employees; in these instances, African-Americans employed prior to the Wilson administration were either offered early retirement, transferred or fired.[36] Since the overwhelming majority of black civilian employees of the federal government worked for either the Treasury, Department of Commerce (mainly for the statistics bureau) or the Postal Service, these measures had a devastating impact on the previously prosperous community of African-American federal civil servants.[37]

Discrimination in the federal hiring process increased even further after 1914, when the Civil Service Commission instituted a new policy, requiring job applicants to submit a photo with their application. The Civil Service Commission claimed the photograph requirement was implemented in order to prevent instances of applicant fraud, even though only 14 cases of impersonation or attempted impersonation in the application process had been uncovered by the CSC in the year leading up. [38]

As a federal enclave, Washington D.C. had long offered African-Americans greater opportunities for employment and less glaring discrimination. In 1919, black soldiers returning to the city after serving in WWI, were outraged to find Jim Crow now in effect; told they could not return to jobs they held prior to the war, with many noting they couldn’t even enter the same buildings they used to work in. Booker T. Washington, visited the capital to investigate claims African-Americans had been virtually shut out of the city's bureaucracy, described the situation: “(I) had never seen the colored people so discouraged and bitter as they are at the present time.”[39]

Reaction of prominent African-Americans

In 1912, despite his southern roots and record at Princeton, Wilson became the first Democrat to receive widespread support from the African American community in a presidential election.[40] Wilson's African-American supporters, many of whom had crossed party lines to vote for him in 1912, were bitterly disappointed and protested these changes.[34]

For a time, Wilson‘s most prominent supporter in the black community was scholar and activist, W.E.B. DuBois. In 1912, DuBois came to campaign enthusiastically on Wilson’s behalf, endorsing him as a “liberal Southerner“.[41] DuBois, a seasoned political voice in the African-American community, had previously been a Republican, but like many black Americans by 1912, felt the GOP had deserted them, especially during the Taft administration. Like most African-Americans, DuBois originally dismissed Wilson’s candidacy out of hand. After briefly supporting Teddy Roosevelt, (before coming to feel his the Bull Moose Party as unwilling to confront civil rights)[42] he resolved instead to support Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debbs. However, during the 1912 campaign, Wilson surprised of many appeared highly responsive to the concerns of the black community, and promised to answer their grievances if elected. DuBois observed that no candidate from either major party in recent memory openly expressed such sentiments. African-Americans rallied in support of Wilson across the country and many had high hopes for Wilson’s presidency, some expected only modest improvements and still others felt contented that at least Wilson would not regress on civil rights. Following the election DuBois wrote to Wilson that all he and his people desired in return for the overwhelming support they gave him was their basic civil and human rights.[43]

These hopes were almost immediately dashed however. Less than six months into his first term, DuBois wrote Wilson another letter, this time lamenting the fact his administration had given aid and comfort to every hateful enemy the Negro community knew and imploring him to change course.[44]

Wilson in turn defended his administration's segregation policy. In a July 1913 letter responding to civil rights activist Oswald Garrison Villard, arguing that segregation removed "friction" between the races.[34] DuBois, who out of support Wilson in 1912, had gone so far as to resign his leadership position in the Socialist Party, wrote a scathing editorial in 1914 attacking Wilson for allowing the widespread dismissal of federal workers for no offense other than their race and decrying his refusal to keep true to his campaign promises to the black community.[45]

African-Americans in the Armed Forces

While segregation had been present in the army prior to Wilson, its severity increased significantly following his election. During Wilson's first term, the army and navy refused to commission new black officers.[46] Black officers already serving experienced increased discrimination and were often forced out or discharged on dubious grounds.[47] Following the entry of the U.S. into WWI, the War Department drafted hundreds of thousands of blacks into the army, draftees were paid equally regardless of race. Commissioning of African-Americans officers resumed but units remained segregated and most all-black units were led by white officers.[48]

Unlike the army, the U.S. Navy was never formally segregated. Following Wilson’s appointment of Josephus Daniels as Secretary of the Navy, a system of Jim Crow was swiftly implemented; with ships, training facilities, restrooms, and cafeterias all becoming segregated.[34] While Daniels significantly expanded opportunities for advancement and training available to white sailors, by the time the U.S. entered WWI, African-American sailors had been relegated almost entirely to mess and custodial duties, often assigned to act as servants for white officers.[49]

Response to race riots and lynchings

In response to the demand for industrial labor, the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South surged in 1917 and 1918. This migration sparked race riots, including the East St. Louis riots of 1917. In response to these riots, but only after much public outcry, Wilson asked Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory if the federal government could intervene to "check these disgraceful outrages." However, on the advice of Gregory, Wilson did not take direct action against the riots.[50] In 1918, Wilson spoke out against lynchings, stating, "I say plainly that every American who takes part in the action of mob or gives it any sort of continence is no true son of this great democracy but its betrayer, and ...[discredits] her by that single disloyalty to her standards of law and of rights."[51] In 1919, another series of race riots occurred in Chicago, Omaha, and two dozen other major cities in the North. The federal government did not become involved, just as it had not become involved previously.[52]

White House screening of The Birth of a Nation

During Wilson's presidency, D. W. Griffith's film The Birth of a Nation (1915) was the first motion picture to be screened in the White House.[53] Wilson agreed to screen the film at the urging of Thomas Dixon Jr., a Johns Hopkins classmate who wrote the book on which The Birth of a Nation was based.[54] The film, while revolutionary in its cinematic technique, glorified the Ku Klux Klan and portrayed blacks as uncouth and uncivilized.

Wilson and only Wilson is quoted (three times) in the film as a scholar of American history. Wilson made no protest over the misquotation of his words. According to some historians, after seeing the film Wilson felt Dixon had misrepresented his views, however. Wilson was personally opposed to the Ku Klux Klan; in his book quoted from in the movie, he argued the reason so many Southerners joined the Klan was desperation brought about by abusive Reconstruction era governments.[55] In terms of Reconstruction, Wilson held the common southern view that the South was demoralized by northern carpetbaggers and that overreach on the part of the Radical Republicans justified extreme measures to reassert democratic, white majority control of Southern state governments.[56] Dixon has been described as a “professional racist”, who used both his pen and pulpit (as a Baptist minister) to promote white supremacy and it is highly unlikely Wilson wasn’t well aware of Dixon’s views before the screening.[57][58]

Though Wilson was not initially critical of the film, he increasingly distanced himself from it as public backlash began to mount. The White House screening was initially used to promote the film. Dixon was able to attract prominent figures for other screenings[59] and overcome attempts to block the movie‘s release by claiming Birth of a Nation was endorsed by the President.[60] Not until April 30, 1915, months after the White House screening, did Wilson release to the press a letter his chief of staff, Joseph Tumulty, had written on his behalf to a member of Congress who had objected to the screening. The letter states Wilson had been "unaware of the character of the play before it was presented and has at no time expressed his approbation of it. Its exhibition at the White House was a courtesy extended to an old acquaintance."[61][62]

Historians have generally concluded that Wilson probably said that The Birth of a Nation was like "writing history with lightning", but reject the allegation that Wilson remarked, "My only regret is that it is all so terribly true."[63][64]

Views on white immigrants and other minorities

Wilson purportedly lamented the contamination of American bloodlines by the "sordid and hapless elements" coming from southern and eastern Europe.[65]

Despite claims he harbored anti-Semitic prejudices, Wilson appointed the first Jewish-American to the Surpeme Court, Louis Brandeis. Wilson did so knowing as both a Jew and staunch progressive, Brandeis would be a divisive nominee who’d face an uphill confirmation. Brandeis vividly contrasted with Wilson’s first appointment, the openly bigoted James McReynolds, who prior to joining the court had served as Wilson’s first Attorney General. On a personal level, McReynold’s was widely seen by his peers and as a mean spirited bigot, whose disrespect was so extreme he’d turn his chair around to face the wall whenever African-American attorneys addressed the court for oral arguments.[66] An unapologetic anti-Semite as well, McReynolds refused to sign opinions by any of his Jewish colleagues on the court.

It should be noted, though Wilson appointed easily the most overtly intolerant Judge in modern times (if not ever) in the form of McReynolds; his legacy to the Supreme Court was overall much more favorable towards racial equality than not. While Brandeis and McReynolds were appointees who cancelled each other out ideologically, Wilson’s third appointment to the bench, John Hessin Clarke, was a progressive who aligned himself closely with Brandeis and the Court’s liberal wing. This point also requires context however; whereas Brandeis and McReynolds served until 1939 and 1941 respectively, Clarke resigned from his lifetime appointment in 1922, after barely 5 years on the bench. Among his reasons for quitting, Clarke cited bullying from McReynolds as at least partial motivation. Ultimately McReynolds sat on the Supreme Court longer than any other Wilson nominee, being both the first and last Wilson nominee on the court. Unlike his other prominent racist appointments, Wilson purportedly expressed remorse over McReynolds, allegedly calling it his "greatest regret."[67]

Assessment and legacy

Ross Kennedy writes that Wilson's support of segregation complied with predominant public opinion.[68] A. Scott Berg argues Wilson accepted segregation as part of a policy to "promote racial progress... by shocking the social system as little as possible."[69] The ultimate result of this policy would be an unprecedented expansion of segregation within the federal bureaucracy; with fewer opportunities for employment and promotion open to African-Americans than before.[70] Historian Kendrick Clements argues that "Wilson had none of the crude, vicious racism of James K. Vardaman or Benjamin R. Tillman, but he was insensitive to African-American feelings and aspirations."[71]

In the wake of the Charleston church shooting, during a debate over the removal of Confederate monuments, some individuals demanded the removal of Wilson's name from institutions affiliated with Princeton due to his administration's segregation of government offices.[72][73] On June 26, 2020, Princeton University removed Wilson's name from its public policy school due to his "racist thinking and policies."[74] The Princeton University Board of Trustees voted to remove Wilson's name from the university's School of Public and International Affairs, changing the name to the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. The Board also accelerated the retirement of the name of a soon-to-be-closed residential college, changing the name from Wilson College to First College. However, the Board did not change the name of the university's highest honor for an undergraduate alumnus or alumna, The Woodrow Wilson Award, because it is the result of a gift. The Board stated that when the university accepted that gift, it took on a legal obligation to name the prize for Wilson.[75]

See Also

References

- ^ O'Reilly, Kenneth (1997). "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (17): 117–121. doi:10.2307/2963252. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2963252

- ^ Foner, Eric. "Expert Report of Eric Foner". The Compelling Need for Diversity in Higher Education. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on May 5, 2006.

- ^ Turner-Sadler, Joanne (2009). African American History: An Introduction. Peter Lang. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-4331-0743-6.

President Wilson's racist policies are a matter of record.

- ^ Wolgemuth, Kathleen L. (1959). "Woodrow Wilson and Federal Segregation". The Journal of Negro History. 44 (2): 158–173. doi:10.2307/2716036. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2716036. S2CID 150080604.

- ^ Feagin, Joe R. (2006). Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression. CRC Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-415-95278-1.

Wilson, who loved to tell racist 'darky' jokes about black Americans, placed outspoken segregationists in his cabinet and viewed racial 'segregation as a rational, scientific policy'.

- ^ Gerstle, Gary (2008). John Milton Cooper Jr. (ed.). Reconsidering Woodrow Wilson: Progressivism, Internationalism, War, and Peace. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center For Scholars. p. 103.

- ^ Cooper (2009), p. 17

- ^ White (1925), ch. 2

- ^ O'Toole, Patricia (2018). The Moralist: Woodrow Wilson and the World He Made. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-9809-4.

- ^ Auchinloss (2000), ch. 1

- ^ O'Reilly, Kenneth (1997). "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (17): 117–121. doi:10.2307/2963252. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2963252

- ^ O'Reilly, Kenneth (1997). "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (17): 117–121. doi:10.2307/2963252. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2963252

- ^ Benbow, Mark E. (2010). "Birth of a Quotation: Woodrow Wilson and "Like Writing History with Lightning"". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 9 (4): 509–533. doi:10.1017/S1537781400004242. JSTOR 20799409.

- ^ O'Reilly, Kenneth (1997). "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (17): 117–121. doi:10.2307/2963252. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2963252

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Benbowwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wilson, Woodrow (1916). A History of the American People. Vol. 5. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 64.

- ^ Skowronek, S. (2006), The Reassociation of Ideas and Purposes: Racism, Liberalism, and the American Political Tradition," at page 391.

- ^ Heckscher (1991), p. 110.

- ^ Heckscher (1991), p. 115.

- ^ O'Reilly, Kenneth (1997). "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (17): 117–121. doi:10.2307/2963252. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2963252

- ^ O'Reilly, Kenneth (1997). "The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (17): 117–121. doi:10.2307/2963252. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2963252.

- ^ Wesley, Charles H. 1950. The History of Alpha Phi Alpha: A Development in Negro College Life (6th ed.). Chicago: Foundation.

- ^ Berg (2013), pp. 307, 311

- ^ Stern, Sheldon N, "Just Why Exactly Is Woodrow Wilson Rated so Highly by Historians? It's a Puzzlement", Columbia College of Arts and Sciences at the George Washington University. historynewsnetwork.org/article/160135. Published August 23, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Missed Manners: Wilson Lectures a Black Leader". historymatters.gmu.edu. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ www.politico.com/story/2017/02/theodore-roosevelt-reviews-race-relations-feb-13-1905-234938

- ^ "African-American Postal Workers in the 20th Century - Who We Are - USPS". about.usps.com. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ Eric S. Yellen, "Racism in the Nation's Service: Government Workers and the Color Line in Woodrow Wilson's America", North Carolina University Press (2013), at page 4

- ^ Meier, August; Rudwick, Elliott (1967). "The Rise of Segregation in the Federal Bureaucracy, 1900–1930". Phylon. 28 (2): 178–184. doi:10.2307/273560. JSTOR 273560.

- ^ Yellen, 124-131.

- ^ Yellin, 127

- ^ DuBois, 456.

- ^ W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, "My Impressions of Woodrow Wilson", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 58, No. 4 (Oct., 1973), at 455-456.

- ^ a b c d e Kathleen L. Wolgemuth, "Woodrow Wilson and Federal Segregation", The Journal of Negro History Vol. 44, No. 2 (Apr. 1959), pp. 158–173, accessed March 10, 2016

- ^ Berg (2013), p. 307

- ^ Lewis, David Levering (1993). W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race 1868–1919. New York City: Henry Holt and Co. p. 332. ISBN 9781466841512.

- ^ Yellin, 124-129.

- ^ Glenn, 91, citing December 1937 issue of The Postal Alliance.

- ^ www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/11/woodrow-wilson-racism-federal-agency-segregation-213315

- ^ Kenneth O’Reilly, “The Jim Crow Policies of Woodrow Wilson,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 17 (Autumn, 1997), p. 117.

- ^ Du Bois, W. E. B. (1956-10-20). "I Won't Vote". www.hartford-hwp.com. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ Id.

- ^ Wolgemuth, Kathleen, “Woodrow Wilson’s Appointment Policy ans the Negro”, The Journal of Southern History. Vol. 24, No. 4 (Nov., 1958), pp. 457-471. Published By: Southern Historical Association. www.jstor.org/stable/2954673?seq=1. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ Lewis, p. 334-335

- ^ Lewis, p. 334-335

- ^ Lewis, p. 332

- ^ Rawn James, Jr. (January 22, 2013). The Double V: How Wars, Protest, and Harry Truman Desegregated America's Military. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-1-60819-617-3. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ James J. Cooke, The All-Americans at War: The 82nd Division in the Great War, 1917–1918 (1999)

- ^ Jack D. Foner, Blacks and the Military in American History: A New Perspective (New York, 1974), 124.

- ^ Cooper (2009), pp. 407–408

- ^ Cooper (2009), pp. 409–410

- ^ Rucker, Walter C.; Upton, James N. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. Greenwood. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-313-33301-9.

- ^ Stokes (2007), p. 111.

- ^ Berg (2013), pp. 95, 347–348.

- ^ Link, (1956), pp. 253–254.

- ^ Gerstle, Gary (2008). John Milton Cooper Jr. (ed.). Reconsidering Woodrow Wilson: Progressivism, Internationalism, War, and Peace. Washington D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center For Scholars. p. 104.

- ^ Raymond A. Cook, “The Man behind The Birth of a Nation," North Carolina Historical Review, 39 (Oct. 1962), 519–40; Corliss, “D. W. Griffiths The Birth of a Nation 100 Years Later."

- ^ Benbow, Mark (October 2010). "Birth of a Quotation: Woodrow Wilson and 'Like Writing History with Lightning'". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 9 (4): 509–533.

- ^ "Chief Justice and Senators at 'Movie'". Washington Herald. February 20, 1915. p. 4.

- ^ Franklin, John Hope (Autumn 1979). "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History". Massachusetts Review. 20 (3): 417–434. JSTOR 25088973.

- ^ Berg (2013), pp. 349–350.

- ^ "Dixon's Play Is Not Indorsed by Wilson". Washington Times. April 30, 1915. p. 6.

- ^ Stokes (2007), p. 111; Cooper (2009), p. 272.

- ^ Benbow, Mark E. (2010). "Birth of a Quotation: Woodrow Wilson and "Like Writing History with Lightning"". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 9 (4): 509–533. doi:10.1017/S1537781400004242. JSTOR 20799409.

- ^ Skowronek, Stephen (2006). "The Reassociation of Ideas and Purposes: Racism, Liberalism, and the American Political Tradition". American Political Science Review. 100 (3): 389. doi:10.1017/S0003055406062253. S2CID 17516798.

- ^ "James C. McReynolds". Oyez Project Official Supreme Court media. Chicago Kent College of Law. Retrieved March 20, 2012

- ^ Berg, 400

- ^ Kennedy, Ross A. (2013). A Companion to Woodrow Wilson. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 171–174. ISBN 978-1-118-44540-2.

- ^ Berg (2013), p. 306

- ^ "The Federal Government and Negro Workers Under President Woodrow Wilson", Maclaury, Judson (Historian for the U.S. Department of Labor)https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/shfgpr00. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Clements (1992), p. 45

- ^ Wolf, Larry (December 3, 2015). "Woodrow Wilson's name has come and gone before". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Jaschik, Scott (April 5, 2016). "Princeton Keeps Wilson Name". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Princeton To Remove Woodrow Wilson's Name From Public Policy School". NPR.org. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "Board of Trustees' decision on removing Woodrow Wilson's name from public policy school and residential college". Princeton University. Retrieved June 28, 2020.