Pushkalavati: Difference between revisions

DenghiùComm (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m Updated coin legend |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

==Pushkalavati in the Ramayana== |

==Pushkalavati in the Ramayana== |

||

[[File:Pushkalavati coin Circa 58-12 BC.jpg|thumb|Pushkalavati mint. ''Obverse'': Zebu with '' |

[[File:Pushkalavati coin Circa 58-12 BC.jpg|thumb|Pushkalavati mint. ''Obverse'': Zebu with greek ''ταυροϛ'' ('tauros' meaning 'bull) above, ''vaṣabha'' (cf. Sanskrit vṛṣabha = bull) in [[Kharosthi]] at the bottom. ''Reverse'': [[Tyche]] of Pushkalavati, wearing mural crown, holding a flower. ''Pakhalavati [Devata]'' (cf. Sanskrit 'Puṣkalāvatī devatā' i.e. 'the goddess of Puṣkalāvatī city') in Kharosthi<ref>{{Cite web|title=Catalog of Gāndhārī Texts|url=https://gandhari.org/catalog?textID=2529&seqID=39743|access-date=2021-03-19|website=gandhari.org}}</ref> up right, ''Drupasaya'' in Kharosthi down left. Time of [[Azes I]], circa 58-12 BCE.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Castro |first1=Andrea (Angelo Andrea) A. A. Di |title=Crowns, Horns and Goddesses Appropriation of Symbols in Gandhāra and Beyond |page=39 |url=https://www.academia.edu/31704024/Crowns_Horns_and_Goddesses_Appropriation_of_Symbols_in_Gandh%C4%81ra_and_Beyond? |language=en}}</ref>]] |

||

In the concluding portion of the ([[Ramayana]]) Uttarakhanda or Supplemental Book (chaps. 101, 113-41, 200), the descendants of [[Rama]] and his brothers are described as the founders of the great cities and kingdoms which flourished in Western India.<ref> |

In the concluding portion of the ([[Ramayana]]) Uttarakhanda or Supplemental Book (chaps. 101, 113-41, 200), the descendants of [[Rama]] and his brothers are described as the founders of the great cities and kingdoms which flourished in Western India.<ref> |

||

[https://books.google.com/books?id=k8kGAAAAMAAJ&dq=Pushkalavati+uttarakhanda&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=Pushkalavati+uttarakhanda Gandhara and Its Art Tradition, Ajit Ghose, Mahua Publishing Company, 1978, p. 14]</ref> |

[https://books.google.com/books?id=k8kGAAAAMAAJ&dq=Pushkalavati+uttarakhanda&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=Pushkalavati+uttarakhanda Gandhara and Its Art Tradition, Ajit Ghose, Mahua Publishing Company, 1978, p. 14]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:24, 19 March 2021

پُشْكَلآوَتي | |

The remains of the original mound, Bala Hisar Swat river and Bala Hisar mound just beyond (center of the photograph). | |

| Alternative name | Pushkalavati |

|---|---|

| Location | Outskirts of Charsadda Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

| Coordinates | 34°10′05″N 71°44′10″E / 34.168°N 71.736°E |

| Type | Ancient capital city |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 1400 BCE |

| Periods | Gandhara |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1902 |

| Archaeologists | Sir John Marshall Sir Mortimer Wheeler |

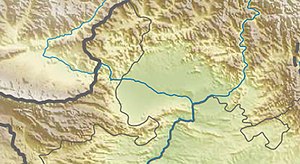

Pushkalavati (Sanskrit: पुष्कलावती; Template:Lang-ps) IAST: Puṣkalāvatī, Greek: Peukelaotis), and later Shaikhan Dheri, was the capital of the Gandhara kingdom.[1] Its ruins are located on the outskirts of the modern city of Charsadda, in Charsadda District, in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 28 kilometres (17 miles) northeast of Peshawar. Its ruins are located on the banks of Swat River, near its junction with Kabul River, with the earliest archaeological remains from 1400 to 800 BCE in Bala Hisar mound.[2][3] Pushkalavati was the capital of the ancient Gandhara kingdom before the 6th century BCE. It later became an Achaemenid regional capital, and it remained an important city until the 2nd century CE. According to Ramayana this city was named after Rama's brother BHARAT's son Pushkala who founded this city, Bharat ruled Gandhara and later the region of pushkalavati was given to Pushkala. After accession Pushkala founded and settled this city.

The region around ancient Pushkulavati was recorded in the Zoroastrian Zend Avesta as Vaēkərəta, or the seventh most beautiful place on earth created by Ahura Mazda. It was known as the "crown jewel" of Bactria, and held sway over nearby ancient Taxila'.[4]

Etymology

Pushkalavati (Sanskrit: पुष्कलावती, IAST: Puṣkalāvatī) means Lotus City in Sanskrit. According to the Ramayana, it was named Pushkalavati because it was founded by Pushkala, the son of Bharat (and hence nephew of Hindu deity Rama).

Ruins

The ruins of Pushkalavati consist of many stupas and the sites of two ancient cities.

Bala Hisar

Bala Hisar site (34°10′05″N 71°44′10″E / 34.168°N 71.736°E) in this area was first occupied in the 2nd millennium BCE.[5][6] The C14 dating of early deposits in Bala Hisar, bearing "Soapy red"/red burnished ware, is 1420-1160 BCE, and this early phase lasted from 1400 to 800 BCE,[7] the second phase took place until around 500 BCE featuring bowls in typical "grooved" red burnished ware.[8]

In later 6th century BCE, Pushkalavati became the capital of the Achaemenid Gandhara satrapy following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley.[9] The location was first excavated in 1902 by the archaeologist John Marshall. Sir Mortimer Wheeler conducted some excavations there in 1962, and identified an occupation from the Achaemenid period and various Achaemenid remains.[10]

According to Arrian, the city then surrendered in 327/326 BCE to Alexander the Great, who established a garrison in it.[11]

Later in the regions historical chronology, King Ashoka built a stupa there which was described by Xuanzang when he visited in 630 CE, which to this day remains unidentified and undiscovered.

Peucela and Shaikhan Dheri

The Bactrian Greeks built a new city (Peucela (Template:Lang-el) or Peucelaitis (Template:Lang-el) at the mound currently known as Shaikhan Dheri (34°10′41″N 71°44′35″E / 34.178°N 71.743°E), which lies one kilometre north from Bala Hissar on the other side of Sambor River, the branch of River Jinde.[12][13] This city was established in second century BCE until the second century CE,[14] occupied by Parthian, Sakas and Kushans.

Two early Buddhist manuscripts recently found in the region, known as avadanas, written in Gandhari language around 1st century CE (now in the British Library Collection of Gandharan Scrolls)[15] mention the name of the city as Pokhaladi.[16][17][18]

In the 2nd century CE, river changed its course and city was flooded. The town moved to the site of the modern village of Rajjar. The last reference to Pushkalavati as Po-shi-ki-lo-fa-ti[19] was recorded in the account of the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang in 7th century C.E.,[20] and subsequently, after the region was conquered by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1001 AD, the name Gandhara was not used anymore, and in all probability the following period is when Pushkalavati became known as Shaikhan Dheri, as Dheri means mound/hill in Pashto,[21] which is related to Persian language.

The former city's ruins were partly excavated by Ahmad Hasan Dani in 1960s. There are still many mounds at Mir Ziarat, at Rajar and Shahr-i-Napursan which are still unexcavated.

Pushkalavati and Prang

The city of Pushkalavati was situated at the confluence of Swat and Kabul rivers. Three different branches of Kabul river meet there. That specific place is still called Prang and considered sacred. A grand graveyard is situated to the north of Prang where the local people bring their dead for burial. This graveyard is considered to be among the largest graveyards in the world.

Pushkalavati in the Ramayana

In the concluding portion of the (Ramayana) Uttarakhanda or Supplemental Book (chaps. 101, 113-41, 200), the descendants of Rama and his brothers are described as the founders of the great cities and kingdoms which flourished in Western India.[26]

Bharata the brother of Rama had two sons, Taksha and Pushkala. The former founded Taksha-sila or Taxila, to the east of the Indus, and known to Alexander and the Greeks as Taxila. The latter founded Pushkala-vati or Pushkalavati, to the west of the Indus, and known to Alexander and the Greeks as Peukelaotis. Thus the sons of Bharat are said to have founded kingdoms which flourished on either side of the Indus river. [27]

See also

References

- ^ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. ISBN 9788172110284.

- ^ Petrie, Cameron, 2013. "Charsadda", in D.K. Chakrabarti and M. Lal (eds.), History of Ancient India III: The Texts, Political History and Administration til c. 200 BC, Vivekananda International Foundation, Aryan Books International, Delhi, p. 515.

- ^ Coningham, R.A.E. and C. Batt, 2007. "Dating the Sequence", in R.A.E. Coningham and I. Ali (eds.), Charsadda: The British-Pakistani Excavations at the Bala Hisar, Society for South Asian Studies Monograph No. 5, BAR International Series 1709, Archaeopress, Oxford, pp. 93-98

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Gandhara Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Investigating ancient Pushkalavati Pushkalavati Archaeological Research Project

- ^ Ali et al. 1998: 6–14; Young 2003: 37–40; Coningham 2004: 9.

- ^ Petrie, Cameron, 2013. "Charsadda", in D.K. Chakrabarti and M. Lal (eds.), History of Ancient India III: The Texts, Political History and Administration til c. 200 BC, Vivekananda International Foundation, Aryan Books International, Delhi, p. 515.

- ^ Petrie, Cameron, 2013. "Charsadda", in D.K. Chakrabarti and M. Lal (eds.), History of Ancient India III: The Texts, Political History and Administration til c. 200 BC, Vivekananda International Foundation, Aryan Books International, Delhi, p. 516.

- ^ Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing, 2011, p. 32 ISBN 0875868592

- ^ Wheeler, Mortimer (1962). Charsada a metropolis of the North-West Frontier. p. Introduction.

- ^ "From Bazaria Alexander marched against Peukelaotis, seated not far from the Indus, which being surrendered to him, he placed a garrison in it, and “proceeded,” according to Arrian, “to take many other small towns situated on that river"" in Archaeological Survey of India. Government central Press. 1871. p. 102.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan, 1963. Pushkalavati: The Lotus City, Archaeological Guide Series No. 1, Peshawar University, Peshawar, p. 5.

- ^ Khan, M. Nasim, 2005. "Terracotta Seal-Impressions from Bala Hisar, Charsadda", in Ancient Pakistan, Vol XVI, p. 13.

- ^ Litvinsky, B.A., 1999. "Cities and Urban Life in the Kushan Kingdom", in (eds.) Janos Harmatta, B.N. Puri, and G.F. Etemadi, History of Civilizations of Central Asia Vol. II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, p. 292.

- ^ British Library Collection of Gandharan Scrolls

- ^ Baums, Stefan, (2019). "A survey of place names in Gandhari inscriptions and a new oil lamp from Malakand", in (eds.) Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart, The Geography of Gandharan Art: Proceedings of the Second International Workshop of the Gandhara Connections Project, University of Oxford, 22nd - 23rd March 2018, Archaeopress, Archaeopress, Oxford, p. 169.

- ^ Manuscript CKM 2 British Library Collection

- ^ Manuscript CKM 14 British Library Collection

- ^ Beal, Samuel, (ed. & trans.), 1884. Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, Volume 2, Author: Hiuen Tsang, London.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan, 1963. "Pushkalavati: The Lotus City", Archaeological Guide Series No. 1, Peshawar University, Peshawar, p. 1.

- ^ https://glosbe.com/ps/en/%D8%BA%D9%88%D9%86%DA%89%DB%8D

- ^ a b "CNG: Printed Auction Triton XV. ATTICA, Athens. Circa 500/490-485/0 BC. AR Tetradrachm (21mm, 16.75 g, 11h)". www.cngcoins.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ "CNG: Printed Auction Triton XV. INDIA, Pre-Mauryan (Gandhara). Period of Achaemenid Rule. Circa 5th century BC. Cast AR Cake Ingot". www.cngcoins.com.

- ^ "Catalog of Gāndhārī Texts". gandhari.org. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Castro, Andrea (Angelo Andrea) A. A. Di. Crowns, Horns and Goddesses Appropriation of Symbols in Gandhāra and Beyond. p. 39.

- ^ Gandhara and Its Art Tradition, Ajit Ghose, Mahua Publishing Company, 1978, p. 14

- ^ Dwaraka Prasad Sharma. "Shrimad Valmiki Ramayan - Sanskrit Text with Hindi Translation- DP Sharma 10 volumes" – via Internet Archive.

External links

- Investigating ancient Pushkalavati Pushkalavati Archaeological Research Project

- Map of Gandhara archaeological sites, from the Huntington Collection, Ohio State University (large file)