Orlando Gibbons: Difference between revisions

fmt |

→Legacy: Remove duplicate mention of Gould comparisons. Tag: references removed |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

Gibbons's death, on 5 June 1625, is regularly marked in [[King's College Chapel, Cambridge]], by the singing of his music at Evensong.<ref>[http://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/choir/about/history.html The Choir of King's College, Cambridge » History of the Choir] ''www.kings.cam.ac.uk'', accessed 28 February 2020</ref> A number of Gibbons's church anthems were included in the ''[[Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems]]''.{{sfn|Morris|1978|p=}} |

Gibbons's death, on 5 June 1625, is regularly marked in [[King's College Chapel, Cambridge]], by the singing of his music at Evensong.<ref>[http://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/choir/about/history.html The Choir of King's College, Cambridge » History of the Choir] ''www.kings.cam.ac.uk'', accessed 28 February 2020</ref> A number of Gibbons's church anthems were included in the ''[[Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems]]''.{{sfn|Morris|1978|p=}} |

||

He was praised in his time by a visit in 1624 from the French ambassador, [[Charles de L'Aubespine]], who stated upon entering Westminster Abbey that “At the entrance, the organ was touched by the best finger of that age, Mr. Orlando Gibbons."{{sfn|Huray|2001}} Musicologist and composer, [[Frederick Ouseley]], dubbed him to be the "English Palestrina"<ref>Grove 1900, pp. 71</ref>{{refn|This is in reference to the revered polyphonic Italian composer, [[Giovanni Palestrina]].|group=n}} |

He was praised in his time by a visit in 1624 from the French ambassador, [[Charles de L'Aubespine]], who stated upon entering Westminster Abbey that “At the entrance, the organ was touched by the best finger of that age, Mr. Orlando Gibbons."{{sfn|Huray|2001}} Musicologist and composer, [[Frederick Ouseley]], dubbed him to be the "English Palestrina"<ref>Grove 1900, pp. 71</ref>{{refn|This is in reference to the revered polyphonic Italian composer, [[Giovanni Palestrina]].|group=n}}. Gibbons paved the way for a future generation of [[Chronological list of English classical composers|English composers]] by perfecting the Byrd's foundations of the [[English Madrigal School|English madrigal]] as well as both full and verse anthems, and especially by teaching music to his oldest son, [[Christopher Gibbons|Christopher]], who in turn taught [[John Blow]], [[Pelham Humfrey]] and most notably [[Henry Purcell]], the English pioneer of the [[Baroque music|Baroque era]].{{sfn|Turbet|2016}} The modern music critic [[John Rockwell]] claimed that the oeuvre of Gibbons: "all attested not merely to a significant figure in music's past but to a composer who can still speak directly to the present."{{sfn|Rockwell|1984}} |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 00:11, 19 April 2021

Orlando Gibbons (bapt. 25 December 1583 – 5 June 1625) was an English composer, virginalist and organist who was one of the last masters of the English Virginalist School and English Madrigal School. By the 1610s he was the leading composer and organist in England, with a career cut short by his sudden death in 1625. As a result, Gibbons's oeuvre was not as large as that of his contemporaries, like the elder William Byrd,[2] but his compositional versatility led to him having written significant works in virtually every form of his day. He is often seen as a transitional figure from the Renaissance to the Baroque periods.

Born in Oxford, Gibbons was born into a musical family where his father—William Gibbons—was a wait, his brothers—Edward, Ellis and Ferdinand—were musicians and Orlando being expected to follow the musical tradition. It is not known under whom he studied, although it may have been with his father, an older brother or Byrd as he was the most famous composer of the time. Irrespective of his education, he was musically proficient enough to be appointed an unsalaried member of the Chapel Royal in May 1603 and a full-fledged gentleman of the Chapel Royal as junior organist by 1605. By 1606 he had graduated from King's College, Cambridge with a Bachelor of Music degree.

Throughout his professional career, Gibbons had increasingly good relations with many important people of the English court. King James I and Prince Charles were supportive patrons and others such as Sir Christopher Hatton, even became close friends. Along with Byrd and John Bull, Gibbons was the youngest contributor to the first printed collection of English keyboard music, Parthenia, and published other compositions in his lifetime, notably the First Set of Madrigals and Motets which includes the best known English madrigal: The Silver Swan. Other important compositions include This Is the Record of John, the 8-part full anthem O Clap Your Hands Together and 2 settings of Evensong. The most important position achieved by Gibbons was his appointment in 1623 as the organist at Westminster Abbey which he held for 2 years until his death on the June 5th, 1625.

Gibbons developed Byrd's foundations of the English madrigal, full and verse anthems, and by doing so he exerted significant influence on subsequent English composers. This generation included his oldest son Christopher, who would teach John Blow, Pelham Humfrey and Henry Purcell, the English pioneer of the Baroque era. Gibbons has been described as "not merely to a significant figure in music's past but to a composer who can still speak directly to the present."[3]

Life and career

Birthplace and background

Gibbons was born in Oxford. Until the mid-20th century he was believed to have been born in Cambridge.[4][5] This was accepted as fact by his contemporaries, stated in multiple early biographies and even recorded on a monument in Canterbury Cathedral, erected in his memory soon after his death.[5][6] It is even possible that Gibbons himself thought that he was born in Cambridge, since he spent most of his life there and only the first 4–5 years of his life in Oxford.[6][7] Matters are made more confusing as his father had lived in Cambridge for at least 10 years, 1–3 years before the birth of Orlando.[8] Therefore, even though 17th-century biographer Anthony Wood discovered a record of an "Orlando Gibbons" being baptised in St. Martin's Church, Oxford, it was assumed that Gibbons was born in Cambridge but baptized in Oxford.[6][9] Modern historians have proved the claim that he was born in Cambridge to be incorrect. Not only was the baptismal record shown to be authentic, but it was discovered that Orlando's parents both resided in Oxford at the time of his birth, confirming that Orlando was born in Oxford and baptized at St. Martin's, Oxford.[10][11][12]

Early life

Gibbons was born to William and Mary[n 2] Gibbons as probably the seventh[n 3] of nine surviving children[n 4] in Oxford, where his father was a city councillor and head of the town waits.[14][n 5] There is no surviving record of the date of his birth, but he is recorded as being baptised at St. Martin's[n 6] on Christmas Day 1583.[10] It would be consistent with the normal practice of the time that Gibbons was born no more than a week before his baptism.[15] Gibbons's father had previously lived in Cambridge where he was also the head of the town waits and around 1588, when Orlando was 4–5 years old, the Gibbons family moved back to Cambridge and William resumed his previous post there.[16][17]

Orlando was born into a musical family: not only was his father a musician, but his oldest brother, Edward, was a composer and master of the Choir of King's College, Cambridge.[18][19] His second brother, Ellis, was a promising composer but died prematurely, and his third brother, Ferdinando, may have eventually taken their father's place as a wait.[20][21] Not much else is known about Orlando Gibbons's youth, but being born into a musical family he was probably instructed on various instruments by his father or older brothers.[15] At the age of 12, he became a member of Edward's Choir of King's College, Cambridge on 14 February 1596.[22] He was a regular member of the choir until some time in the Michaelmas term of 1598. In the Easter term (summer term) of the same year he enrolled at King's College, Cambridge as a sizar, meaning he paid reduced fees but had to do various menial tasks.[23][15][24] From 1598–99 Gibbons's name appeared sporadically in the chorus member logs, suggesting that, if not a clerical error, he continued to sing from time to time, perhaps for special occasions.[10][15] Gibbons's composition teacher is unknown, but it is likely to have been an older brother or his father, as they were experienced musicians.[15] Edward is often proposed as the most likely candidate by historians, as he was the oldest brother, had achieved a Bachelor of Music degree at King's College, Cambridge, and was already experienced as the master of the choruses there.[15] Another possible composition teacher is William Byrd, who was at least 40 years his senior and the most respected English composer at the time.[25] Gibbons and Byrd along with the composer John Bull later collectively published music and since Bull was a student of Byrd's, Gibbons may very well also have been.[17] Regardless of how his musical education came about, Gibbons was known to be composing music by the end of his time at the choir in 1599, at age 15–16.[15]

Early career and marriage

Gibbons's abilities had reached the point to allow him become a Musician of the Chapel Royal on 19 May 1603.[15] His name appears at this time in a Cheque book from the Chapel Royal for services to King James I, as he was likely Gentleman Extraordinary (unpaid substitute) awaiting the vacancy of a paid position.[26] 1603 was a year of mixed fortunes: he received his first position as a professional musician, but in the same year both his mother and his brother Ellis died.[15] Eventually Gibbons's awaited vacancy occurred with the death of Arthur Cook, and on 21 March 1605 he secured the prestigious position of Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, as the junior chapel organist.[27][9] Edward Gibbons's friendship with the former organist, Arthur Cook, and the senior chapel organist, John Bull, may have helped his younger brother secure this position.[28][29] Either way, becoming a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal at the age of only 21 would have been an impressive feat at the time and he kept this position until the end of his life.[23][30]

In 1606 Gibbons married Elizabeth Patten on 17 February.[23][31] Her father, John Patten, was a Yeoman of the Vestry in the Chapel Royal, and probably well acquainted with Gibbons, which would have helped to bring about the marriage.[32] When Patten died in 1623, he made Gibbons his sole heir, residuary legatee and left 200 pounds for his children.[33] The same year, shortly after his marriage, Orlando graduated from Cambridge with the degree of Bachelor in Music.[33][34] Gibbons and his wife lived in Woolstaple (now Bridge Street) which was in the parish of St Margaret's, Westminster, the church where Gibbons's seven children—James, Alice, Christopher, Ann, Mary, Elizabeth and Orlando.[35]—would be baptised.[36][17][26]

Publishing and patronage

By the 1610s Gibbons had become a composer of high repute and perhaps the best organist in England.[37][38] At around this time he became a close friend of Sir Christopher Hatton, who became an important patron of his.[39] Hatton was the second cousin and heir of the more famous Christopher Hatton, favourite of Queen Elizabeth I of England.[29] In fact, Hatton and his wife, Alice Fanshawe, were probably the namesakes of two of Gibbons's children, Alice and the future composer Christopher.[40][29] The next years saw the publishing of various works by Gibbons, the first of which, his First Set of Madrigals and Motets was published in 1612 under the patronage of Hatton.[26] One of the Madrigals in the set was renowned and probably the most famous English Madrigal, The Silver Swan.[2] Gibbons dedicated the entire set of works to Hatton and said that most of it was composed in Hatton's house:

[The songs] were most of them composed in your owne house, and doe therefore properly belong unto you, as Lord of the Soile; the language they speake you provided them, I onely furnished them with Tongues to utter the same name.

— Harley 1999, p. 37Bridge 1920, p. 36

This quote has been interpreted in suggesting that Hatton wrote some or all of the poems that Gibbons set to music in his First Set of Madrigals and Motets, but there is no evidence to support this.[41] Additionally, it is unlikely that Gibbons was a resident of Hatton's household, although their friendship suggests that Hatton may have set a room aside for him to compose.[42]

Some time in 1612–1613, Gibbons had six works published in the first printed collection of keyboard music, Parthenia, which included works by the older and important composers, Byrd and Bull.[26][41] This publication was to celebrate the marriage of the Princess Elizabeth to Duke Frederick V, the Elector of Palestine.[43] Compositions written around the time of Parthenia, including various anthems dedicated to senior clergy, the pavan Lord Salisbury for Lord Salisbury and the wedding anthem Blessed are all they in 1613 for the Earl of Somerset suggest that he was well associated throughout the court.[26] In 1614 William Leighton published The Teares and Lamentatacions of a Sorrowfull Soule with 2 contributions by Gibbons, O Lord how do my woes increase and O Lord, I lift my heart to Thee.[44] Although he possibly started as early as 1605, Gibbons was the joint organist with Edmund Hooper by at least 1615.[26][35] The same year he received two grants from King James I, worth 150 pounds total.[26][45] These grants were:

For and in consideration of the good and faithful service heretofore done unto ourself by Orlando Gibbons our organist, and divers other good causes and considerations us thereunto moving.

— Fellowes 1951, pp. 37–38

Gibbons continued writing for James I, composing the anthem Great King of Gods and the court song Do not repine, fair sun in celebration of the King's 1617 visit to Scotland.[26]

Late career

By the late 1610s Gibbons was undoubtedly the most important musician and composer at court as Byrd had retired in Essex and Bull had fled to the Low Countries to avoid a charge of adultery.[17][25][26][46][47] In 1617 Gibbons gained the position as keyboard player in an ensemble, organised by John Cooper, for the privy chamber of Prince Charles (later King Charles I).[26][48] Gibbons was the only keyboardist in a group of 17 musicians of whom the Prince himself was thought to have occasionally joined on either the Bass-Viol or Viol da Gamba.[49] It is likely that Gibbons was able to write for this ensemble and had pieces premiered by it.[26] In addition to this, Gibbons probably gained a 3rd position in September 1619, attending the royal privy chamber of James I.[50] His next major work, Fantasies of Three Parts was published around 1620 and dedicated it to Edmund Wry. This seemingly random dedication has provoked much speculation. It may be because Wry could secure Gibbons a better post, or it may be an action of gratitude for having already secured him the post for the royal privy chamber of the King.[51]

While once assumed to be fact, there is now much doubt whether Gibbons received a Doctorate of Music in May 1622. In 1815, Wood stated:

"On the 17th of May, Orlando Gibbons, one of the organists of his majesty's chapel, did supplicate the venerable congregation that he might accumulate the degrees in music; but whether he was admitted to the one, or license to proceed in the other, it appears not."

— Wood 1815, p. 406

This uncertainty has continued until the present day. Gibbons’s 8-part full anthem, O clap your hands was sung on 17 May 1622 at the degree ceremony for William Heather.[52][53][n 7] Heather had financially supported William Camden's creation and maintenance of the Camden Professor of Ancient History chair and in return the university awarded him the honorary degrees of bachelor in music and doctor of music, even though he was not known to be a musician.[42][55] The author Sir John Hawkins and musicologists Edmund Fellowes and David Mateer state unequivocally that Gibbons was awarded a doctorate along with Heather, and cite O clap your hands as the composer’s qualifying exercise for the degree.[4][53][42] Other musicologists – Peter Le Huray, John Harper and John Harley – express some doubt whether Gibbons received a doctorate.[26][56] Specifically, Harley cites a record in the Cheque book of the Chapel Royal that refers to William Heather as "doctor" but Gibbons as "senior organist."[57] The same writer refers to a letter from Camden to William Piers from 18 May 1622 that says Gibbons is a Doctor of Music.[55] Harley suggests that the authenticity of the letter is uncertain, since the original does not survive; he suggests that Camden could have written something such as "G––––s," which an editor assumed to mean Gibbons.[57] The most convincing piece of evidence is thought to be the absence of mention of the supposed doctorate of music on Gibbons's Cambridge monument, erected in his memory when he died.[55] Although the existing evidence seems to support the conclusion that he never achieved a doctorate in music, there is no indisputable evidence to confirm it.[57]

Final years and death

Some time in 1623, George Wither published Hymnes and Songs of the Church in which Gibbons provided the tunes for most of the songs.[58][59] The same year he succeeded John Parsons as the organist at Westminster Abbey, with Thomas Day as junior organist.[60] This was probably the most important position Gibbons had taken in his career thus far and on 7 May 1625 he officiated at the funeral of King James I.[61]

During late May 1625, the English court was preparing to receive Queen Henrietta Maria, whom the now King Charles I of England had married through proxy in France on 1 May.[62] Gibbons and other Chapel Royal members had begun travelling to Canterbury on 31 May when Gibbons suddenly succumbed to an illness, probably a cerebral aneurysm.[26][63][n 8] He died at age 41 in Canterbury and was buried in Canterbury Cathedral.[63][66] His death was a shock to his peers and brought about a post-mortem, although the cause of death aroused less comment than the haste of his burial and his body not being returned to London.[26][67] His wife, Elizabeth, died a little over a year later, in her mid-30s, leaving Orlando's eldest brother, Edward, to care for the orphaned children.[9][68]

Music

One of the most versatile English composers of his time, Gibbons wrote a large number of keyboard works, around thirty fantasias for viols, a number of madrigals (the best-known being "The Silver Swan"), and many popular verse anthems, all to English texts (the best known being "Great Lord of Lords"). Perhaps his best-known verse anthem is This Is the Record of John, which sets an Advent text for solo countertenor or tenor, alternating with full chorus. The soloist is required to demonstrate considerable technical facility, and the work expresses the text's rhetorical force without being demonstrative or bombastic. He also produced two major settings of Evensong, the Short Service and the Second Service, an extended composition combining verse and full sections. Gibbons's full anthems include the expressive O Lord, in thy wrath, and the Ascension Day anthem O clap your hands together (after Psalm 47) for eight voices.

He contributed six pieces to the first printed collection of keyboard music in England, Parthenia (to which he was by far the youngest of the three contributors), published in about 1611. Gibbons's surviving keyboard output comprises some 45 pieces. The polyphonic fantasia and dance forms are the best represented genres. Gibbons's writing exhibits a command of three- and four-part counterpoint. Most of the fantasias are complex, multi-sectional pieces, treating multiple subjects imitatively. Gibbons's approach to melody, in both his fantasias and his dances, features extensive development of simple musical ideas, as for example in Pavane in D minor and Lord Salisbury's Pavan and Galliard.[69]

Legacy

In the 20th century, the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould championed Gibbons's music, and named him as his favourite composer.[70] Gould wrote of Gibbons's hymns and anthems: "ever since my teen-age years this music ... has moved me more deeply than any other sound experience I can think of."[71]

In one interview, Gould compared Gibbons to Beethoven and Webern:

...despite the requisite quota of scales and shakes in such half-hearted virtuoso vehicles as the Salisbury Galliard, one is never quite able to counter the impression of music of supreme beauty that lacks its ideal means of reproduction. Like Beethoven in his last quartets, or Webern at almost any time, Gibbons is an artist of such intractable commitment that, in the keyboard field, at least, his works work better in one's memory, or on paper, than they ever can through the intercession of a sounding-board.

— Payzant 1986, pp. 82–83

Gibbons's death, on 5 June 1625, is regularly marked in King's College Chapel, Cambridge, by the singing of his music at Evensong.[72] A number of Gibbons's church anthems were included in the Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems.[73]

He was praised in his time by a visit in 1624 from the French ambassador, Charles de L'Aubespine, who stated upon entering Westminster Abbey that “At the entrance, the organ was touched by the best finger of that age, Mr. Orlando Gibbons."[26] Musicologist and composer, Frederick Ouseley, dubbed him to be the "English Palestrina"[74][n 9]. Gibbons paved the way for a future generation of English composers by perfecting the Byrd's foundations of the English madrigal as well as both full and verse anthems, and especially by teaching music to his oldest son, Christopher, who in turn taught John Blow, Pelham Humfrey and most notably Henry Purcell, the English pioneer of the Baroque era.[17] The modern music critic John Rockwell claimed that the oeuvre of Gibbons: "all attested not merely to a significant figure in music's past but to a composer who can still speak directly to the present."[3]

References

Notes

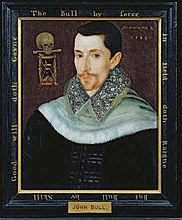

- ^ This portrait is kept at Faculty of music and The Bate Collection of Musical Instruments at the University of Oxford and is only known to be a "copy from a lost original once in the possession of a Mrs. Fussell."[1]

- ^ Her maiden name is unknown.[13]

- ^ The birthdates of two of his sisters, Thomasine and Elizabeth, are uncertain leading to the possibility of Gibbons being the eighth or youngest surviving sibling.

- ^ Their first child, Richard, died as an infant.[7]

- ^ This would indicate that William was either an instrumentalist, singer or perhaps both.

- ^ The Church itself was demolished in 1900 and only one of the towers, The Carfax Tower, survives.

- ^ Often spelled as William Heyther.[42][54]

- ^ A suspicion immediately arose that Gibbons had died of the plague, which was rife in England that year. Two physicians who had been present at his death were ordered to make a report, and performed a post-mortem examination, the account of which survives in The National Archives:

This account is taken to mean that Gibbons died of a cerebral aneurysm.[65]We whose names are here underwritten: having been called to give our counsels to Mr. Orlando Gibbons; in the time of his late and sudden sickness, which we found in the beginning lethargical, or a profound sleep; out of which, we could never recover him, neither by inward nor outward medicines, & then instantly he fell in most strong, & sharp convulsions; which did wring his mouth up to his ears, & his eyes were distorted, as though they would have been thrust out of his head & then suddenly he lost both speech, sight and hearing, & so grew apoplectical & lost the whole motion of every part of his body, & so died. Then here upon (his death being so sudden) rumours were cast out that he did die of the plague, whereupon we . . . caused his body to be searched by certain women that were sworn to deliver the truth, who did affirm that they never saw a fairer corpse. Yet notwithstanding we to give full satisfaction to all did cause the skull to be opened in our presence & we carefully viewed the body, which we found also to be very clean without any show or spot of any contagious matter. In the brain we found the whole & sole cause of his sickness namely a great admirable blackness & syderation in the outside of the brain. Within the brain (being opened) there did issue out abundance of water intermixed with blood & this we affirm to be the only cause of his sudden death.[64]

- ^ This is in reference to the revered polyphonic Italian composer, Giovanni Palestrina.

Citations

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 287.

- ^ a b Fellowes 1951, p. 55.

- ^ a b Rockwell 1984.

- ^ a b Hawkins 1853, p. 573.

- ^ a b Thewlis 1940, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Fellowes 1951, p. 32.

- ^ a b Harley 1999, p. 7.

- ^ Harley 1999, pp. 5–9.

- ^ a b c Wood 1815, p. 406.

- ^ a b c Fellowes 1951, p. 33.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Thewlis 1940, p. 33.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harley 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Turbet 2016.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 28.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 29, 31.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 16, 17.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 34–35.

- ^ a b c Fellowes 1951, p. 35.

- ^ "Definition of sizar". Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ a b Milsom 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Huray 2001.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Harper 2008.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 31.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 32.

- ^ Harley 1999, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Fellowes 1951, p. 36.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 33.

- ^ a b Westminster Abbey.

- ^ Harley 1999, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Bridge 1920, p. 49.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 37.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 38.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 37.

- ^ a b Bridge 1920, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Fellowes 1951, p. 39.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 43.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 51.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Bridge 1920, p. 34.

- ^ Neighbour & Jeans 2001.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 58.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 59.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 62–63.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 63.

- ^ Bridge 1920, p. 42.

- ^ a b Mateer 2008.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Harley 1999, p. 65.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 64–66.

- ^ a b c Harley 1999, p. 66.

- ^ Bridge 1920, p. 43.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 67.

- ^ Harley 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 40.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 41.

- ^ a b Fellowes 1951, p. 44.

- ^ The National Archives, State Papers Domestic, Charles I, 1625, III, 60, quoted in Boden 2005, p. 124

- ^ Lewis 2010.

- ^ Bridge 1920, p. 47.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 45.

- ^ Fellowes 1951, p. 50.

- ^ Apel 1997, pp. 320–323.

- ^ Gould & Cott 2005, p. 65.

- ^ Gould 1990, p. 438.

- ^ The Choir of King's College, Cambridge » History of the Choir www.kings.cam.ac.uk, accessed 28 February 2020

- ^ Morris 1978.

- ^ Grove 1900, pp. 71

Sources

- Books

- Apel, Willi (1997). The History of Keyboard Music to 1700. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21141-7.

- Boden, Anthony (2005). Thomas Tomkins: The Last Elizabethan. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5118-5.

- Bridge, Sir Frederick (2009) [1920]. Twelve Good Musicians: From John Bull to Henry Purcell. London, England: Cornell University Library. ISBN 978-1112520761.

- Fellowes, Edmund H. (1951). Orlando Gibbons and His Family: The Last of the Tudor School of Musicians (2nd ed.). United States: Archon Books. ISBN 978-0-208-00848-0.

- Gould, Glenn (1990). Tim Page (ed.). The Glenn Gould Reader. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-73135-1.

- Gould, Glenn; Cott, Jonathan (2005). Conversations with Glenn Gould. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-11623-5.

- Harley, John (1999). Orlando Gibbons and the Gibbons Family of Musicians. London, England: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-840-14209-9.

- Hawkins, Sir John (1963) [1853]. Novello, Joseph Alfred (ed.). A General History of the Science and Practice of Music. Vol. Volume II (4th ed.). New York, New York: Dover. ISBN 9780486210490.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Lewis, Joseph W. Jr., M.D. (2010). What Killed the Great and Not So Great Composers?. Author House. ISBN 978-1-4520-3438-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Morris, Christopher (1978). The Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems: 34 Anthems for Mixed Voices. Oxford University Press, Music Department. ISBN 978-0-19-353325-7.

- Payzant, Geoffrey (1986). Glenn Gould: Music & Mind. Formac. ISBN 978-0-88780-145-7.

- Wood, Anthony (1815). Bliss, Phillip (ed.). Athenae Oxonienses. Vol. Volume II (3rd ed.). London, England: Printed for F.C. and J. Rivington. OCLC 847943279.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

- Journals and articles

- Anderton, H. Orsmond (1 June 1912). "Orlando Gibbons". The Musical Times. 53 (832): 367–369. doi:10.2307/907324. JSTOR 907324.

- Harper, John (December 1983). "Orlando Gibbons: The Domestic Context of His Music and Christ Church MS 21". The Musical Times. 124 (1690): 767–770. doi:10.2307/962243. JSTOR 962243.

- Harper, John (2008). "Gibbons, Orlando (bap. 1583, d. 1625), composer and keyboard player". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10598. Template:ONBsub

- Huray, Peter Le (2001). "Gibbons, Orlando". In Harper, John (ed.). Grove Music Online. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11092. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Kerman, Joseph (2001). "Byrd, William". In McCarthy, Kerry (ed.). Grove Music Online. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.04487. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Mateer, David (2008). "Heather, William (c. 1563–1627), musician and benefactor". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12849. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Milsom, John (2011). "Byrd, William". In Latham, Alison (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199579037.001.0001. ISBN 9780199579037. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Neighbour, Oliver; Jeans, Susi (2001). "Bull [Boul, Bul, Bol], John". Grove Music Online. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.04294. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Thewlis, George A. (January 1940). "Oxford and the Gibbons Family". Music & Letters. 21 (1): 31–33. doi:10.1093/ml/XXI.1.31. JSTOR 727619.

- Turbet, Richard (2016). "Orlando Gibbons". Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199757824-0172. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Online

- Rockwell, John (11 May 1984). "Music: Orlando Gibbons". New York Times. New York City, New York: The New York Times Company. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Orlando and Christopher Gibbons". Westminster Abbey. London, England: Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

External links

- Free scores

- Free scores by Orlando Gibbons at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Orlando Gibbons in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Orlando Gibbons at the Mutopia Project

- List of compositions by Gibbons, Orlando at the Digital Image Archive of Medieval Music

- Miscellaneous

- Orlando Gibbons at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Works by Orlando Gibbons at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Orlando Gibbons Dedicated Website

- 16th-century births

- 1583 births

- 1625 deaths

- Alumni of King's College, Cambridge

- English Baroque composers

- Burials at Canterbury Cathedral

- Composers for harpsichord

- 16th-century English composers

- English madrigal composers

- English classical composers

- English male classical composers

- Renaissance composers

- English classical organists

- British male organists

- Gentlemen of the Chapel Royal

- Master of the Choristers at Westminster Abbey

- People from Oxford

- 17th-century English composers

- 17th-century classical composers

- 17th-century English musicians

- Choristers of the Choir of King's College, Cambridge