Gelatinous zooplankton: Difference between revisions

Fix Dash apocalypse |

dash disaster clean-up : more |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

===Jelly carbon=== |

===Jelly carbon=== |

||

The global biomass of gelatinous zooplankton, herein collectively referred to as “jelly‐carbon” (jelly‐C), within the upper 200 m of the ocean amounts to 0.038 Pg C.<ref name=Lucas2014>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1111/geb.12169|title = Gelatinous zooplankton biomass in the global oceans: Geographic variation and environmental drivers|year = 2014|last1 = Lucas|first1 = Cathy H.|last2 = Jones|first2 = Daniel O. B.|last3 = Hollyhead|first3 = Catherine J.|last4 = Condon|first4 = Robert H.|last5 = Duarte|first5 = Carlos M.|last6 = Graham|first6 = William M.|last7 = Robinson|first7 = Kelly L.|last8 = Pitt|first8 = Kylie A.|last9 = Schildhauer|first9 = Mark|last10 = Regetz|first10 = Jim|journal = Global Ecology and Biogeography|volume = 23|issue = 7|pages = 701–714|url = http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/507136/1/Lucas%20et%20al%202014%20post%20print.pdf}}</ref> Calculations for mesozooplankton (200 μm to 2 cm) suggest about 0.20 Pg C.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.5194/essd-5-45-2013}}</ref> The short life span of most gelatinous zooplankton, from weeks up to 2 to 12 months,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1038/srep12037|title = The elusive life cycle of scyphozoan jellyfish – metagenesis revisited|year = 2015|last1 = Ceh|first1 = Janja|last2 = Gonzalez|first2 = Jorge|last3 = Pacheco|first3 = Aldo S.|last4 = Riascos|first4 = José M.|journal = Scientific Reports|volume = 5|page = 12037|pmid = 26153534|pmc = 4495463|bibcode = 2015NatSR...512037C}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.2307/1543497|jstor = 1543497|title = Collection and Culture Techniques for Gelatinous Zooplankton|last1 = Raskoff|first1 = Kevin A.|last2 = Sommer|first2 = Freya A.|last3 = Hamner|first3 = William M.|last4 = Cross|first4 = Katrina M.|journal = Biological Bulletin|year = 2003|volume = 204|issue = 1|pages = 68–80|pmid = 12588746|s2cid = 22389317}}</ref> suggests biomass‐production rates above 0.038 Pg C year−1, depending on the assumed mortality rates, which in many cases are species‐specific. This is much smaller than global primary production (50 Pg C year−1),<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1126/science.281.5374.237|title = Primary Production of the Biosphere: Integrating Terrestrial and Oceanic Components|year = 1998|last1 = Field|first1 = C. B.|last2 = Behrenfeld|first2 = M. J.|last3 = Randerson|first3 = J. T.|last4 = Falkowski|first4 = P.|journal = Science|volume = 281|issue = 5374|pages = 237–240|pmid = 9657713|bibcode = 1998Sci...281..237F|url = http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/9gm7074q}}</ref> which translates into export estimates close to 6 Pg C year−1 below 100 m,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1029/2004GB002220|title = Upper ocean ecosystem dynamics and iron cycling in a global three-dimensional model|year = 2004|last1 = Moore|first1 = J. Keith|last2 = Doney|first2 = Scott C.|last3 = Lindsay|first3 = Keith|journal = Global Biogeochemical Cycles|volume = 18|issue = 4|pages = n/a|bibcode = 2004GBioC..18.4028M}}</ref><ref name=Siegel2014>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1002/2013GB004743|title = Global assessment of ocean carbon export by combining satellite observations and food-web models|year = 2014|last1 = Siegel|first1 = D. A.|last2 = Buesseler|first2 = K. O.|last3 = Doney|first3 = S. C.|last4 = Sailley|first4 = S. F.|last5 = Behrenfeld|first5 = M. J.|last6 = Boyd|first6 = P. W.|journal = Global Biogeochemical Cycles|volume = 28|issue = 3|pages = 181–196|bibcode = 2014GBioC..28..181S|hdl = 1912/6668}}</ref>depending on the method used. Globally, gelatinous zooplankton abundance and distribution patterns largely follow those of temperature and dissolved oxygen as well as primary production as the carbon source.<ref name=Lucas2014 /> However, gelatinous zooplankton cope with a wide spectrum of environmental conditions, indicating the ability to adapt and occupy most available ecological niches in a water mass. In terms of Longhurst regions (biogeographical provinces that partition the pelagic environment,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1016/0079-6611(95)00015-1}}</ref><ref name=Longhurst1998>Longhurst, A. R. (1998). ''Ecological geography of the sea'', page 398. Academic Press.</ref> the highest densities of gelatinous zooplankton occur in coastal waters of the Humboldt Current, NE U.S. Shelf, Scotian and Newfoundland shelves, Benguela Current, East China and Yellow Seas, followed by polar regions of the East Bering and Okhotsk Seas, the Southern Ocean, enclosed bodies of water such as the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and the west Pacific waters of the Japan seas and the Kuroshio Current.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1007/ |

The global biomass of gelatinous zooplankton, herein collectively referred to as “jelly‐carbon” (jelly‐C), within the upper 200 m of the ocean amounts to 0.038 Pg C.<ref name=Lucas2014>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1111/geb.12169|title = Gelatinous zooplankton biomass in the global oceans: Geographic variation and environmental drivers|year = 2014|last1 = Lucas|first1 = Cathy H.|last2 = Jones|first2 = Daniel O. B.|last3 = Hollyhead|first3 = Catherine J.|last4 = Condon|first4 = Robert H.|last5 = Duarte|first5 = Carlos M.|last6 = Graham|first6 = William M.|last7 = Robinson|first7 = Kelly L.|last8 = Pitt|first8 = Kylie A.|last9 = Schildhauer|first9 = Mark|last10 = Regetz|first10 = Jim|journal = Global Ecology and Biogeography|volume = 23|issue = 7|pages = 701–714|url = http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/507136/1/Lucas%20et%20al%202014%20post%20print.pdf}}</ref> Calculations for mesozooplankton (200 μm to 2 cm) suggest about 0.20 Pg C.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.5194/essd-5-45-2013}}</ref> The short life span of most gelatinous zooplankton, from weeks up to 2 to 12 months,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1038/srep12037|title = The elusive life cycle of scyphozoan jellyfish – metagenesis revisited|year = 2015|last1 = Ceh|first1 = Janja|last2 = Gonzalez|first2 = Jorge|last3 = Pacheco|first3 = Aldo S.|last4 = Riascos|first4 = José M.|journal = Scientific Reports|volume = 5|page = 12037|pmid = 26153534|pmc = 4495463|bibcode = 2015NatSR...512037C}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.2307/1543497|jstor = 1543497|title = Collection and Culture Techniques for Gelatinous Zooplankton|last1 = Raskoff|first1 = Kevin A.|last2 = Sommer|first2 = Freya A.|last3 = Hamner|first3 = William M.|last4 = Cross|first4 = Katrina M.|journal = Biological Bulletin|year = 2003|volume = 204|issue = 1|pages = 68–80|pmid = 12588746|s2cid = 22389317}}</ref> suggests biomass‐production rates above 0.038 Pg C year−1, depending on the assumed mortality rates, which in many cases are species‐specific. This is much smaller than global primary production (50 Pg C year−1),<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1126/science.281.5374.237|title = Primary Production of the Biosphere: Integrating Terrestrial and Oceanic Components|year = 1998|last1 = Field|first1 = C. B.|last2 = Behrenfeld|first2 = M. J.|last3 = Randerson|first3 = J. T.|last4 = Falkowski|first4 = P.|journal = Science|volume = 281|issue = 5374|pages = 237–240|pmid = 9657713|bibcode = 1998Sci...281..237F|url = http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/9gm7074q}}</ref> which translates into export estimates close to 6 Pg C year−1 below 100 m,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1029/2004GB002220|title = Upper ocean ecosystem dynamics and iron cycling in a global three-dimensional model|year = 2004|last1 = Moore|first1 = J. Keith|last2 = Doney|first2 = Scott C.|last3 = Lindsay|first3 = Keith|journal = Global Biogeochemical Cycles|volume = 18|issue = 4|pages = n/a|bibcode = 2004GBioC..18.4028M}}</ref><ref name=Siegel2014>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1002/2013GB004743|title = Global assessment of ocean carbon export by combining satellite observations and food-web models|year = 2014|last1 = Siegel|first1 = D. A.|last2 = Buesseler|first2 = K. O.|last3 = Doney|first3 = S. C.|last4 = Sailley|first4 = S. F.|last5 = Behrenfeld|first5 = M. J.|last6 = Boyd|first6 = P. W.|journal = Global Biogeochemical Cycles|volume = 28|issue = 3|pages = 181–196|bibcode = 2014GBioC..28..181S|hdl = 1912/6668}}</ref>depending on the method used. Globally, gelatinous zooplankton abundance and distribution patterns largely follow those of temperature and dissolved oxygen as well as primary production as the carbon source.<ref name=Lucas2014 /> However, gelatinous zooplankton cope with a wide spectrum of environmental conditions, indicating the ability to adapt and occupy most available ecological niches in a water mass. In terms of Longhurst regions (biogeographical provinces that partition the pelagic environment,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1016/0079-6611(95)00015-1}}</ref><ref name=Longhurst1998>Longhurst, A. R. (1998). ''Ecological geography of the sea'', page 398. Academic Press.</ref> the highest densities of gelatinous zooplankton occur in coastal waters of the Humboldt Current, NE U.S. Shelf, Scotian and Newfoundland shelves, Benguela Current, East China and Yellow Seas, followed by polar regions of the East Bering and Okhotsk Seas, the Southern Ocean, enclosed bodies of water such as the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and the west Pacific waters of the Japan seas and the Kuroshio Current.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1007/s10750-012-1039-7}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1525/bio.2012.62.2.9|title = Questioning the Rise of Gelatinous Zooplankton in the World's Oceans|year = 2012|last1 = Condon|first1 = Robert H.|last2 = Graham|first2 = William M.|last3 = Duarte|first3 = Carlos M.|last4 = Pitt|first4 = Kylie A.|last5 = Lucas|first5 = Cathy H.|last6 = Haddock|first6 = Steven H.D.|last7 = Sutherland|first7 = Kelly R.|last8 = Robinson|first8 = Kelly L.|last9 = Dawson|first9 = Michael N.|last10 = Decker|first10 = Mary Beth|last11 = Mills|first11 = Claudia E.|last12 = Purcell|first12 = Jennifer E.|last13 = Malej|first13 = Alenka|last14 = Mianzan|first14 = Hermes|last15 = Uye|first15 = Shin-Ichi|last16 = Gelcich|first16 = Stefan|last17 = Madin|first17 = Laurence P.|journal = Bioscience|volume = 62|issue = 2|pages = 160–169|s2cid = 2721425}}</ref><ref name=Lucas2014 /> Large amounts of jelly‐C biomass that are reported from coastal areas of open shelves and semienclosed seas of North America, Europe, and East Asia come from coastal stranding data.<ref>[http://www.jellywatch.org/ JellyWatch Home] ''jellywatch.org''. Accessed 17 April 2022.</ref><ref name=Lebrato2019 /> |

||

===Carbon export=== |

===Carbon export=== |

||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

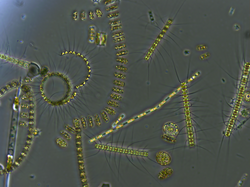

[[File:Doliólido.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3| [[Doliolid]]s, gelatinous [[tunicate]]s belonging to the class of [[Thaliacean]]s, are found everywhere on [[continental shelves]]. Thaliaceans play an important role in the ecology of the sea. Their dense faecal pellets sink to the bottom of the oceans and this may be a major part of the worldwide [[carbon cycle]].<ref>[http://www.economist.com/science/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13688170 Thaliaceans and the carbon cycle]</ref>]] |

[[File:Doliólido.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3| [[Doliolid]]s, gelatinous [[tunicate]]s belonging to the class of [[Thaliacean]]s, are found everywhere on [[continental shelves]]. Thaliaceans play an important role in the ecology of the sea. Their dense faecal pellets sink to the bottom of the oceans and this may be a major part of the worldwide [[carbon cycle]].<ref>[http://www.economist.com/science/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13688170 Thaliaceans and the carbon cycle]</ref>]] |

||

Ocean carbon export is typically estimated from the flux of sinking particles that are either caught in sediment traps{{hsp}}<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1016/ |

Ocean carbon export is typically estimated from the flux of sinking particles that are either caught in sediment traps{{hsp}}<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1016/0198-0149(87)90117-8}}</ref> or quantified from videography,<ref>Jackson et al., 1997</ref> and subsequently modeled using sinking rates.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1016/0198-0149(87)90086-0}}</ref> Biogeochemical models{{hsp}}<ref name=Gehlen2006>{{cite journal |doi = 10.5194/bg-3-521-2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1029/2012MS000178|title = Global ocean biogeochemistry model HAMOCC: Model architecture and performance as component of the MPI-Earth system model in different CMIP5 experimental realizations|year = 2013|last1 = Ilyina|first1 = Tatiana|last2 = Six|first2 = Katharina D.|last3 = Segschneider|first3 = Joachim|last4 = Maier-Reimer|first4 = Ernst|last5 = Li|first5 = Hongmei|last6 = Núñez-Riboni|first6 = Ismael|journal = Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems|volume = 5|issue = 2|pages = 287–315|bibcode = 2013JAMES...5..287I}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.5194/bg-12-6955-2015}}</ref> are normally parameterized using particulate organic matter data (e.g., 0.5–1,000 μm marine snow and fecal pellets) that were derived from laboratory experiments{{hsp}}<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.4319/lo.2008.53.5.1878|title = Ballast, sinking velocity, and apparent diffusivity within marine snow and zooplankton fecal pellets: Implications for substrate turnover by attached bacteria|year = 2008|last1 = Ploug|first1 = Helle|last2 = Iversen|first2 = Morten Hvitfeldt|last3 = Fischer|first3 = Gerhard|journal = Limnology and Oceanography|volume = 53|issue = 5|pages = 1878–1886|bibcode = 2008LimOc..53.1878P}}</ref> or from sediment trap data.<ref name=Gehlen2006 /> These models do not include jelly‐C (except larvaceans,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1016/j.dsr.2010.06.008|title = Marine snow originating from appendicularian houses: Age-dependent settling characteristics|year = 2010|last1 = Lombard|first1 = Fabien|last2 = Kiørboe|first2 = Thomas|journal = Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers|volume = 57|issue = 10|pages = 1304–1313|bibcode = 2010DSRI...57.1304L}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.3354/meps08273|title = Prediction of ecological niches and carbon export by appendicularians using a new multispecies ecophysiological model|year = 2010|last1 = Lombard|first1 = F.|last2 = Legendre|first2 = L.|last3 = Picheral|first3 = M.|last4 = Sciandra|first4 = A.|last5 = Gorsky|first5 = G.|journal = Marine Ecology Progress Series|volume = 398|pages = 109–125|bibcode = 2010MEPS..398..109L}}</ref> not only because this carbon transport mechanism is considered transient/episodic and not usually observed, and mass fluxes are too big to be collected by sediment traps,ref name=Siegel2014 /> but also because models aim to simplify the biotic compartments to facilitate calculations. Furthermore, jelly‐C deposits tend not to build up at the seafloor over a long time, such as phytodetritus (Beaulieu, 2002), being consumed rapidly by demersal and benthic organisms{{hsp}}<ref name=Sweetman2014 /> or decomposed by microbes.<ref name=Tinta2016 /> The jelly‐C sinking rate is governed by organism size, diameter, biovolume, geometry,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1080/00071617700650231|title = The form resistance of chitan fibres attached to the cells of ''Thalassiosira'' fluviatilis ''Hustedt''|year = 1977|last1 = Walsby|first1 = A.E.|last2 = Xypolyta|first2 = Anastasia|journal = British Phycological Journal|volume = 12|issue = 3|pages = 215–223}}</ref> density,<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.1007/s00227-007-0807-9}}</ref> and drag coefficients.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.4319/lo.2010.55.5.2085|title = Variability in the average sinking velocity of marine particles|year = 2010|last1 = McDonnell|first1 = Andrew M. P.|last2 = Buesseler|first2 = Ken O.|journal = Limnology and Oceanography|volume = 55|issue = 5|pages = 2085–2096|bibcode = 2010LimOc..55.2085M}}</ref> In 2013, Lebrato et al. determined the average sinking speed of jelly‐C using Cnidaria, Ctenophora, and Thaliacea samples, which ranged from 800 to 1,500 m day−1 (salps: 800–1,200 m day−1; scyphozoans: 1,000–1,100 m d−1; ctenophores: 1,200–1,500 m day−1; pyrosomes: 1,300 m day−1).<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.4319/lo.2013.58.3.1113|title = Jelly biomass sinking speed reveals a fast carbon export mechanism|year = 2013|last1 = Lebrato|first1 = Mario|last2 = Mendes|first2 = Pedro de Jesus|last3 = Steinberg|first3 = Deborah K.|last4 = Cartes|first4 = Joan E.|last5 = Jones|first5 = Bethan M.|last6 = Birsa|first6 = Laura M.|last7 = Benavides|first7 = Roberto|last8 = Oschlies|first8 = Andreas|journal = Limnology and Oceanography|volume = 58|issue = 3|pages = 1113–1122|bibcode = 2013LimOc..58.1113L|url = http://oceanrep.geomar.de/21291/1/1113.pdf}}</ref> Jelly‐C model simulations suggest that, regardless of taxa, higher latitudes are more efficient corridors to transfer jelly‐C to the seabed owing to lower remineralization rates.<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.4319/lo.2011.56.5.1917|title = Depth attenuation of organic matter export associated with jelly falls|year = 2011|last1 = Lebrato|first1 = Mario|last2 = Pahlow|first2 = Markus|last3 = Oschlies|first3 = Andreas|last4 = Pitt|first4 = Kylie A.|last5 = Jones|first5 = Daniel O. B.|last6 = Molinero|first6 = Juan Carlos|last7 = Condon|first7 = Robert H.|journal = Limnology and Oceanography|volume = 56|issue = 5|pages = 1917–1928|bibcode = 2011LimOc..56.1917L|hdl = 10072/43275}}</ref> In subtropical and temperate regions, significant decomposition takes place in the water column above 1,500 m depth, except in cases where jelly‐C starts sinking below the thermocline. In shallow‐water coastal regions, time is a limiting factor, which prevents remineralization while sinking and results in the accumulation of decomposing jelly‐C from a variety of taxa on the seabed. This suggests that gelatinous zooplankton transfer most biomass and carbon to the deep ocean, enhancing coastal carbon fluxes via DOC and DIC, fueling microbial and megafaunal/macrofaunal scavenging communities. However, the absence of satellite‐derived jelly‐C measurements (such as [[Marine primary production|primary production]]){{hsp}}<ref>{{cite journal |doi = 10.4319/lo.1997.42.1.0001|title = Photosynthetic rates derived from satellite-based chlorophyll concentration|year = 1997|last1 = Behrenfeld|first1 = Michael J.|last2 = Falkowski|first2 = Paul G.|journal = Limnology and Oceanography|volume = 42|issue = 1|pages = 1–20|bibcode = 1997LimOc..42....1B}}</ref> and the limited number of global zooplankton biomass data sets make it challenging to quantify global jelly‐C production and transfer efficiency to the ocean's interior.<ref name=Lebrato2019 /> |

||

{{clear}} |

{{clear}} |

||

Revision as of 15:01, 27 April 2021

Gelatinous zooplankton are fragile animals that live in the water column in the ocean. Their delicate bodies have no hard parts and are easily damaged or destroyed.[2] Gelatinous zooplankton are often transparent.[3] All jellyfish are gelatinous zooplankton, but not all gelatinous zooplankton are jellyfish. The most commonly encountered organisms include ctenophores, medusae, salps, and Chaetognatha in coastal waters. However, almost all marine phyla, including Annelida, Mollusca and Arthropoda, contain gelatinous species, but many of those odd species live in the open ocean and the deep sea and are less available to the casual ocean observer.[4] Many gelatinous plankters utilize mucous structures in order to filter feed.[5] Gelatinous zooplankton have also been called "Gelata".[6]

As prey

| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

Jellyfish are slow swimmers, and most species form part of the plankton. Traditionally jellyfish have been viewed as trophic dead ends, minor players in the marine food web, gelatinous organisms with a body plan largely based on water that offers little nutritional value or interest for other organisms apart from a few specialised predators such as the ocean sunfish and the leatherback sea turtle.[7][1] That view has recently been challenged. Jellyfish, and more gelatinous zooplankton in general, which include salps and ctenophores, are very diverse, fragile with no hard parts, difficult to see and monitor, subject to rapid population swings and often live inconveniently far from shore or deep in the ocean. It is difficult for scientists to detect and analyse jellyfish in the guts of predators, since they turn to mush when eaten and are rapidly digested.[7] But jellyfish bloom in vast numbers, and it has been shown they form major components in the diets of tuna, spearfish and swordfish as well as various birds and invertebrates such as octopus, sea cucumbers, crabs and amphipods.[8][1] "Despite their low energy density, the contribution of jellyfish to the energy budgets of predators may be much greater than assumed because of rapid digestion, low capture costs, availability, and selective feeding on the more energy-rich components. Feeding on jellyfish may make marine predators susceptible to ingestion of plastics."[1]

As predators

According to a 2017 study, narcomedusae consume the greatest diversity of mesopelagic prey, followed by physonect siphonophores, ctenophores and cephalopods.[9] The importance of the so called "jelly web" is only beginning to be understood, but it seems medusae, ctenophores and siphonophores can be key predators in deep pelagic food webs with ecological impacts similar to predator fish and squid. Traditionally gelatinous predators were thought ineffectual providers of marine trophic pathways, but they appear to have substantial and integral roles in deep pelagic food webs.[9]

Pelagic siphonophores, a diverse group of cnidarians, are found at most depths of the ocean - from the surface, like the Portuguese man of war, to the deep sea. They play important roles in ocean ecosystems, and are among the most abundant gelatinous predators.[10]

-

Gelatinous zooplankton like this narcomedusan can be key predators in deep pelagic food webs

-

Narcomedusa ingesting a salp chain

-

Helmet jellyfish feeding on an armhook squid

-

Trachymedusa with a large red mysid in its gut

Jelly pump

Biological oceanic processes, primarily carbon production in the euphotic zone, sinking and remineralization, govern the global biological carbon soft‐tissue pump.[12] Sinking and laterally transported carbon‐laden particles fuel benthic ecosystems at continental margins and in the deep sea.[13][14] Marine zooplankton play a major role as ecosystem engineers in coastal and open ocean ecosystems because they serve as links between primary production, higher trophic levels, and deep‐sea communities.[15][14][16] In particular, gelatinous zooplankton (Cnidaria, Ctenophora, and Chordata, namely, Thaliacea) are universal members of plankton communities that graze on phytoplankton and prey on other zooplankton and ichthyoplankton. They also can rapidly reproduce on a time scale of days and, under favorable environmental conditions, some species form dense blooms that extend for many square kilometers.[17] These blooms have negative ecological and socioeconomic impacts by reducing commercially harvested fish species,[18] limiting carbon transfer to other trophic levels,[19] enhancing microbial remineralization, and thereby driving oxygen concentrations down close to anoxic levels.[20][11]

Jelly carbon

The global biomass of gelatinous zooplankton, herein collectively referred to as “jelly‐carbon” (jelly‐C), within the upper 200 m of the ocean amounts to 0.038 Pg C.[21] Calculations for mesozooplankton (200 μm to 2 cm) suggest about 0.20 Pg C.[22] The short life span of most gelatinous zooplankton, from weeks up to 2 to 12 months,[23][24] suggests biomass‐production rates above 0.038 Pg C year−1, depending on the assumed mortality rates, which in many cases are species‐specific. This is much smaller than global primary production (50 Pg C year−1),[25] which translates into export estimates close to 6 Pg C year−1 below 100 m,[26][27]depending on the method used. Globally, gelatinous zooplankton abundance and distribution patterns largely follow those of temperature and dissolved oxygen as well as primary production as the carbon source.[21] However, gelatinous zooplankton cope with a wide spectrum of environmental conditions, indicating the ability to adapt and occupy most available ecological niches in a water mass. In terms of Longhurst regions (biogeographical provinces that partition the pelagic environment,[28][29] the highest densities of gelatinous zooplankton occur in coastal waters of the Humboldt Current, NE U.S. Shelf, Scotian and Newfoundland shelves, Benguela Current, East China and Yellow Seas, followed by polar regions of the East Bering and Okhotsk Seas, the Southern Ocean, enclosed bodies of water such as the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and the west Pacific waters of the Japan seas and the Kuroshio Current.[30][31][21] Large amounts of jelly‐C biomass that are reported from coastal areas of open shelves and semienclosed seas of North America, Europe, and East Asia come from coastal stranding data.[32][11]

Carbon export

Large amounts of jelly‐C are quickly transferred to and remineralized on the seabed in coastal areas, including estuaries, lagoons and subtidal/intertidal zones,[15] shelves and slopes,[33][34][35] the deepsea.[36] and even entire continental margins such as in the Mediterranean Sea.[37] Jelly‐C transfer begins when gelatinous zooplankton die at a given “death depth” (exit depth), continues as biomass sinks through the water column, and terminates once biomass is remineralized during sinking or reaches the seabed, and then decays. Jelly‐C per se represents a transfer of “already exported” particles (below the mixed later, euphotic or mesopelagic zone), originated in primary production since gelatinous zooplankton “repackage” and integrate this carbon in their bodies, and after death transfer it to the ocean's interior. While sinking through the water column, jelly‐C is partially or totally remineralized as dissolved organic/inorganic carbon and nutrients (DOC, DIC, DON, DOP, DIN and DIP)[38][39][40] and any left overs further experience microbial decomposition or are scavenged by macrofauna and megafauna once on the seabed.[41][42] Despite the high lability of jelly‐C,[43][39] a remarkably large amount of biomass arrives at the seabed below 1,000 m. During sinking, jelly‐C biochemical composition changes via shifts in C:N:P ratios as observed in experimental studies.[20][44][45] Yet realistic jelly‐C transfer estimates at the global scale remain in their infancy, preventing a quantitative assessment of the contribution to the biological carbon soft‐tissue pump.[11]

Ocean carbon export is typically estimated from the flux of sinking particles that are either caught in sediment traps [47] or quantified from videography,[48] and subsequently modeled using sinking rates.[49] Biogeochemical models [50][51][52] are normally parameterized using particulate organic matter data (e.g., 0.5–1,000 μm marine snow and fecal pellets) that were derived from laboratory experiments [53] or from sediment trap data.[50] These models do not include jelly‐C (except larvaceans,[54][55] not only because this carbon transport mechanism is considered transient/episodic and not usually observed, and mass fluxes are too big to be collected by sediment traps,ref name=Siegel2014 /> but also because models aim to simplify the biotic compartments to facilitate calculations. Furthermore, jelly‐C deposits tend not to build up at the seafloor over a long time, such as phytodetritus (Beaulieu, 2002), being consumed rapidly by demersal and benthic organisms [41] or decomposed by microbes.[42] The jelly‐C sinking rate is governed by organism size, diameter, biovolume, geometry,[56] density,[57] and drag coefficients.[58] In 2013, Lebrato et al. determined the average sinking speed of jelly‐C using Cnidaria, Ctenophora, and Thaliacea samples, which ranged from 800 to 1,500 m day−1 (salps: 800–1,200 m day−1; scyphozoans: 1,000–1,100 m d−1; ctenophores: 1,200–1,500 m day−1; pyrosomes: 1,300 m day−1).[59] Jelly‐C model simulations suggest that, regardless of taxa, higher latitudes are more efficient corridors to transfer jelly‐C to the seabed owing to lower remineralization rates.[60] In subtropical and temperate regions, significant decomposition takes place in the water column above 1,500 m depth, except in cases where jelly‐C starts sinking below the thermocline. In shallow‐water coastal regions, time is a limiting factor, which prevents remineralization while sinking and results in the accumulation of decomposing jelly‐C from a variety of taxa on the seabed. This suggests that gelatinous zooplankton transfer most biomass and carbon to the deep ocean, enhancing coastal carbon fluxes via DOC and DIC, fueling microbial and megafaunal/macrofaunal scavenging communities. However, the absence of satellite‐derived jelly‐C measurements (such as primary production) [61] and the limited number of global zooplankton biomass data sets make it challenging to quantify global jelly‐C production and transfer efficiency to the ocean's interior.[11]

Monitoring

Because of its fragile structure, image acquisition of gelatinous zooplankton requires the assistance of computer visioning. Automated recognition of zooplankton in sample deposits is possible by utilising technologies such as Tikhonov regularization, support vector machines and genetic programming.[62]

-

The salp, another example of a gelatinous tunicate, is often found in the form of a colonial chain

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Hays, Graeme C.; Doyle, Thomas K.; Houghton, Jonathan D.R. (2018). "A Paradigm Shift in the Trophic Importance of Jellyfish?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (11): 874–884. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.09.001. PMID 30245075.

- ^ Lalli, C.M. & Parsons, T.R. (2001) Biological Oceanography. Butterworth-Heinemann.

- ^ Johnsen, S. (2000) Transparent Animals. Scientific American 282: 62-71.

- ^ Nouvian, C. (2007) The Deep. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Hamner, W. M.; Madin, L. P.; Alldredge, A. L.; Gilmer, R. W.; Hamner, P. P. (1975). "Underwater observations of gelatinous zooplankton: Sampling problems, feeding biology, and behavior1". Limnology and Oceanography. 20 (6): 907–917. Bibcode:1975LimOc..20..907H. doi:10.4319/lo.1975.20.6.0907. ISSN 1939-5590.

- ^ HADDOCK, S.D.H. (2004) A golden age of gelata: past and future research on planktonic ctenophores and cnidarians. Hydrobiologia 530/531: 549-556.

- ^ a b Hamilton, G. (2016) "The secret lives of jellyfish: long regarded as minor players in ocean ecology, jellyfish are actually important parts of the marine food web". Nature, 531(7595): 432-435. doi:10.1038/531432a

- ^ Cardona, L., De Quevedo, I.Á., Borrell, A. and Aguilar, A. (2012) "Massive consumption of gelatinous plankton by Mediterranean apex predators". PLOS ONE, 7(3): e31329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031329

- ^ a b Choy, C.A., Haddock, S.H. and Robison, B.H. (2017) "Deep pelagic food web structure as revealed by in situ feeding observations". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1868): 20172116. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.2116.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Munro, Catriona; Siebert, Stefan; Zapata, Felipe; Howison, Mark; Damian-Serrano, Alejandro; Church, Samuel H.; Goetz, Freya E.; Pugh, Philip R.; Haddock, Steven H.D.; Dunn, Casey W. (2018). "Improved phylogenetic resolution within Siphonophora (Cnidaria) with implications for trait evolution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 127: 823–833. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.06.030. PMC 6064665. PMID 29940256.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ a b c d e f Lebrato, Mario; Pahlow, Markus; Frost, Jessica R.; Küter, Marie; Jesus Mendes, Pedro; Molinero, Juan‐Carlos; Oschlies, Andreas (2019). "Sinking of Gelatinous Zooplankton Biomass Increases Deep Carbon Transfer Efficiency Globally". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 33 (12): 1764–1783. Bibcode:2019GBioC..33.1764L. doi:10.1029/2019GB006265.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Buesseler, K. O.; Lamborg, C. H.; Boyd, P. W.; Lam, P. J.; Trull, T. W.; Bidigare, R. R.; Bishop, J. K. B.; Casciotti, K. L.; Dehairs, F.; Elskens, M.; Honda, M.; Karl, D. M.; Siegel, D. A.; Silver, M. W.; Steinberg, D. K.; Valdes, J.; Van Mooy, B.; Wilson, S. (2007). "Revisiting Carbon Flux Through the Ocean's Twilight Zone". Science. 316 (5824): 567–570. Bibcode:2007Sci...316..567B. doi:10.1126/science.1137959. PMID 17463282. S2CID 8423647.

- ^ Koppelmann, R., & Frost, J. (2008). "The ecological role of zooplankton in the twilight and dark zones of the ocean". In: L. P. Mertens (Ed.), Biological Oceanography Research Trends, pages 67–130. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

- ^ a b Robinson, Carol; Steinberg, Deborah K.; Anderson, Thomas R.; Arístegui, Javier; Carlson, Craig A.; Frost, Jessica R.; Ghiglione, Jean-François; Hernández-León, Santiago; Jackson, George A.; Koppelmann, Rolf; Quéguiner, Bernard; Ragueneau, Olivier; Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun; Robison, Bruce H.; Tamburini, Christian; Tanaka, Tsuneo; Wishner, Karen F.; Zhang, Jing (2010). "Mesopelagic zone ecology and biogeochemistry – a synthesis". Deep Sea Research Part Ii: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 57 (16): 1504–1518. Bibcode:2010DSRII..57.1504R. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2010.02.018.

- ^ a b . doi:10.1007/s10750-012-1046-8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Robison, B. H.; Reisenbichler, K. R.; Sherlock, R. E. (2005). "Giant Larvacean Houses: Rapid Carbon Transport to the Deep Sea Floor". Science. 308 (5728): 1609–1611. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1609R. doi:10.1126/science.1109104. PMID 15947183. S2CID 730130.

- ^ Condon, R. H.; Duarte, C. M.; Pitt, K. A.; Robinson, K. L.; Lucas, C. H.; Sutherland, K. R.; Mianzan, H. W.; Bogeberg, M.; Purcell, J. E.; Decker, M. B.; Uye, S.-i.; Madin, L. P.; Brodeur, R. D.; Haddock, S. H. D.; Malej, A.; Parry, G. D.; Eriksen, E.; Quinones, J.; Acha, M.; Harvey, M.; Arthur, J. M.; Graham, W. M. (2013). "Recurrent jellyfish blooms are a consequence of global oscillations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (3): 1000–1005. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1000C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1210920110. PMC 3549082. PMID 23277544.

- ^ . doi:10.1007/s10750-008-9583-x.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Condon, R. H.; Steinberg, D. K.; Del Giorgio, P. A.; Bouvier, T. C.; Bronk, D. A.; Graham, W. M.; Ducklow, H. W. (2011). "Jellyfish blooms result in a major microbial respiratory sink of carbon in marine systems". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (25): 10225–10230. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810225C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015782108. PMC 3121804. PMID 21646531.

- ^ a b . doi:10.1007/s10750-012-1042-z.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c Lucas, Cathy H.; Jones, Daniel O. B.; Hollyhead, Catherine J.; Condon, Robert H.; Duarte, Carlos M.; Graham, William M.; Robinson, Kelly L.; Pitt, Kylie A.; Schildhauer, Mark; Regetz, Jim (2014). "Gelatinous zooplankton biomass in the global oceans: Geographic variation and environmental drivers" (PDF). Global Ecology and Biogeography. 23 (7): 701–714. doi:10.1111/geb.12169.

- ^ . doi:10.5194/essd-5-45-2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ceh, Janja; Gonzalez, Jorge; Pacheco, Aldo S.; Riascos, José M. (2015). "The elusive life cycle of scyphozoan jellyfish – metagenesis revisited". Scientific Reports. 5: 12037. Bibcode:2015NatSR...512037C. doi:10.1038/srep12037. PMC 4495463. PMID 26153534.

- ^ Raskoff, Kevin A.; Sommer, Freya A.; Hamner, William M.; Cross, Katrina M. (2003). "Collection and Culture Techniques for Gelatinous Zooplankton". Biological Bulletin. 204 (1): 68–80. doi:10.2307/1543497. JSTOR 1543497. PMID 12588746. S2CID 22389317.

- ^ Field, C. B.; Behrenfeld, M. J.; Randerson, J. T.; Falkowski, P. (1998). "Primary Production of the Biosphere: Integrating Terrestrial and Oceanic Components". Science. 281 (5374): 237–240. Bibcode:1998Sci...281..237F. doi:10.1126/science.281.5374.237. PMID 9657713.

- ^ Moore, J. Keith; Doney, Scott C.; Lindsay, Keith (2004). "Upper ocean ecosystem dynamics and iron cycling in a global three-dimensional model". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 18 (4): n/a. Bibcode:2004GBioC..18.4028M. doi:10.1029/2004GB002220.

- ^ Siegel, D. A.; Buesseler, K. O.; Doney, S. C.; Sailley, S. F.; Behrenfeld, M. J.; Boyd, P. W. (2014). "Global assessment of ocean carbon export by combining satellite observations and food-web models". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 28 (3): 181–196. Bibcode:2014GBioC..28..181S. doi:10.1002/2013GB004743. hdl:1912/6668.

- ^ . doi:10.1016/0079-6611(95)00015-1.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Longhurst, A. R. (1998). Ecological geography of the sea, page 398. Academic Press.

- ^ . doi:10.1007/s10750-012-1039-7.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Condon, Robert H.; Graham, William M.; Duarte, Carlos M.; Pitt, Kylie A.; Lucas, Cathy H.; Haddock, Steven H.D.; Sutherland, Kelly R.; Robinson, Kelly L.; Dawson, Michael N.; Decker, Mary Beth; Mills, Claudia E.; Purcell, Jennifer E.; Malej, Alenka; Mianzan, Hermes; Uye, Shin-Ichi; Gelcich, Stefan; Madin, Laurence P. (2012). "Questioning the Rise of Gelatinous Zooplankton in the World's Oceans". Bioscience. 62 (2): 160–169. doi:10.1525/bio.2012.62.2.9. S2CID 2721425.

- ^ JellyWatch Home jellywatch.org. Accessed 17 April 2022.

- ^ Billett, D. S. M.; Bett, B. J.; Jacobs, C. L.; Rouse, I. P.; Wigham, B. D. (2006). "Mass deposition of jellyfish in the deep Arabian Sea". Limnology and Oceanography. 51 (5): 2077–2083. Bibcode:2006LimOc..51.2077B. doi:10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2077.

- ^ Lebrato, M.; Jones, D. O. B. (2009). "Mass deposition event of Pyrosoma atlanticum carcasses off Ivory Coast (West Africa)". Limnology and Oceanography. 54 (4): 1197–1209. Bibcode:2009LimOc..54.1197L. doi:10.4319/lo.2009.54.4.1197.

- ^ Sweetman, Andrew K.; Chapman, Annelise (2011). "First observations of jelly-falls at the seafloor in a deep-sea fjord". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 58 (12): 1206–1211. Bibcode:2011DSRI...58.1206S. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2011.08.006.

- ^ Smith, K. L. Jr.; Sherman, A. D.; Huffard, C. L.; McGill, P. R.; Henthorn, R.; von Thun, S.; Ruhl, H. A.; Kahru, M.; Ohman, M. D. (2014). "Large salp bloom export from the upper ocean and benthic community response in the abyssal northeast Pacific: Day to week resolution". Limnology and Oceanography. 59 (3): 745–757. Bibcode:2014LimOc..59..745S. doi:10.4319/lo.2014.59.3.0745.

- ^ Lebrato, Mario; Molinero, Juan-Carlos; Cartes, Joan E.; Lloris, Domingo; Mélin, Frédéric; Beni-Casadella, Laia (2013). "Sinking Jelly-Carbon Unveils Potential Environmental Variability along a Continental Margin". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e82070. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...882070L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082070. PMC 3867349. PMID 24367499.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Chelsky, Ariella; Pitt, Kylie A.; Welsh, David T. (2015). "Biogeochemical implications of decomposing jellyfish blooms in a changing climate". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 154: 77–83. Bibcode:2015ECSS..154...77C. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2014.12.022. hdl:10072/101243.

- ^ a b Sweetman, Andrew K.; Chelsky, Ariella; Pitt, Kylie A.; Andrade, Hector; Van Oevelen, Dick; Renaud, Paul E. (2016). "Jellyfish decomposition at the seafloor rapidly alters biogeochemical cycling and carbon flow through benthic food-webs". Limnology and Oceanography. 61 (4): 1449–1461. Bibcode:2016LimOc..61.1449S. doi:10.1002/lno.10310.

- ^ . doi:10.1007/s10750-008-9586-7.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Sweetman, Andrew K.; Smith, Craig R.; Dale, Trine; Jones, Daniel O. B. (2014). "Rapid scavenging of jellyfish carcasses reveals the importance of gelatinous material to deep-sea food webs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1796). doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2210. PMC 4213659. PMID 25320167.

- ^ a b Tinta, Tinkara; Kogovšek, Tjaša; Turk, Valentina; Shiganova, Tamara A.; Mikaelyan, Alexander S.; Malej, Alenka (2016). "Microbial transformation of jellyfish organic matter affects the nitrogen cycle in the marine water column — A Black Sea case study". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 475: 19–30. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2015.10.018.

- ^ Ates, Ron M. L. (2017). "Benthic scavengers and predators of jellyfish, material for a review". Plankton and Benthos Research. 12: 71–77. doi:10.3800/pbr.12.71.

- ^ Sempéré, R.; Yoro, SC; Van Wambeke, F.; Charrière, B. (2000). "Microbial decomposition of large organic particles in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea:an experimental approach". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 198: 61–72. Bibcode:2000MEPS..198...61S. doi:10.3354/meps198061.

- ^ Titelman, J.; Riemann, L.; Sørnes, TA; Nilsen, T.; Griekspoor, P.; Båmstedt, U. (2006). "Turnover of dead jellyfish: Stimulation and retardation of microbial activity". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 325: 43–58. Bibcode:2006MEPS..325...43T. doi:10.3354/meps325043.

- ^ Thaliaceans and the carbon cycle

- ^ . doi:10.1016/0198-0149(87)90117-8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Jackson et al., 1997

- ^ . doi:10.1016/0198-0149(87)90086-0.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b . doi:10.5194/bg-3-521-2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ilyina, Tatiana; Six, Katharina D.; Segschneider, Joachim; Maier-Reimer, Ernst; Li, Hongmei; Núñez-Riboni, Ismael (2013). "Global ocean biogeochemistry model HAMOCC: Model architecture and performance as component of the MPI-Earth system model in different CMIP5 experimental realizations". Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems. 5 (2): 287–315. Bibcode:2013JAMES...5..287I. doi:10.1029/2012MS000178.

- ^ . doi:10.5194/bg-12-6955-2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ploug, Helle; Iversen, Morten Hvitfeldt; Fischer, Gerhard (2008). "Ballast, sinking velocity, and apparent diffusivity within marine snow and zooplankton fecal pellets: Implications for substrate turnover by attached bacteria". Limnology and Oceanography. 53 (5): 1878–1886. Bibcode:2008LimOc..53.1878P. doi:10.4319/lo.2008.53.5.1878.

- ^ Lombard, Fabien; Kiørboe, Thomas (2010). "Marine snow originating from appendicularian houses: Age-dependent settling characteristics". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 57 (10): 1304–1313. Bibcode:2010DSRI...57.1304L. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2010.06.008.

- ^ Lombard, F.; Legendre, L.; Picheral, M.; Sciandra, A.; Gorsky, G. (2010). "Prediction of ecological niches and carbon export by appendicularians using a new multispecies ecophysiological model". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 398: 109–125. Bibcode:2010MEPS..398..109L. doi:10.3354/meps08273.

- ^ Walsby, A.E.; Xypolyta, Anastasia (1977). "The form resistance of chitan fibres attached to the cells of Thalassiosira fluviatilis Hustedt". British Phycological Journal. 12 (3): 215–223. doi:10.1080/00071617700650231.

- ^ . doi:10.1007/s00227-007-0807-9.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ McDonnell, Andrew M. P.; Buesseler, Ken O. (2010). "Variability in the average sinking velocity of marine particles". Limnology and Oceanography. 55 (5): 2085–2096. Bibcode:2010LimOc..55.2085M. doi:10.4319/lo.2010.55.5.2085.

- ^ Lebrato, Mario; Mendes, Pedro de Jesus; Steinberg, Deborah K.; Cartes, Joan E.; Jones, Bethan M.; Birsa, Laura M.; Benavides, Roberto; Oschlies, Andreas (2013). "Jelly biomass sinking speed reveals a fast carbon export mechanism" (PDF). Limnology and Oceanography. 58 (3): 1113–1122. Bibcode:2013LimOc..58.1113L. doi:10.4319/lo.2013.58.3.1113.

- ^ Lebrato, Mario; Pahlow, Markus; Oschlies, Andreas; Pitt, Kylie A.; Jones, Daniel O. B.; Molinero, Juan Carlos; Condon, Robert H. (2011). "Depth attenuation of organic matter export associated with jelly falls". Limnology and Oceanography. 56 (5): 1917–1928. Bibcode:2011LimOc..56.1917L. doi:10.4319/lo.2011.56.5.1917. hdl:10072/43275.

- ^ Behrenfeld, Michael J.; Falkowski, Paul G. (1997). "Photosynthetic rates derived from satellite-based chlorophyll concentration". Limnology and Oceanography. 42 (1): 1–20. Bibcode:1997LimOc..42....1B. doi:10.4319/lo.1997.42.1.0001.

- ^ "Looking inside the Ocean: Toward an Autonomous Imaging System for Monitoring Gelatinous Zooplankton". Sensors. 12 (16): 2124. 2016. doi:10.3390/s16122124. ISSN 1424-8220. OCLC 8148647236. PMC 5191104. PMID 27983638. Archived from the original on April 15, 2020 – via DOAJ.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; February 15, 2020 suggested (help); External link in|via=|authors=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Raskoff, K., and R. Hopcroft (2010). Crossota norvegica. Arctic Ocean Diversity. Accessed 25 August 2020.

External links

- Plankton Chronicles Short documentary films & photos

- Ocean Explorer: Gelatinous zooplankton from the Arctic Ocean

- Jellyfish and other gelatinous zooplankton

- PLANKTON NET: information on all types of plankton including gelatinous zooplankton

- Deep-sea gelatinous zooplankton from The Deep (Nouvian, 2007)

![Deep-red jellyfish, a hydrozoan found in the Arctic Ocean at depths below 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[63]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/09/Expl0393_-_Flickr_-_NOAA_Photo_Library.jpg/383px-Expl0393_-_Flickr_-_NOAA_Photo_Library.jpg)