Veganism: Difference between revisions

m Add missing "the" Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

→Toiletries: Removed reference to replacing dental floss with a vegan option. Uncited as well as out of scope for the article as dental floss is plastic ie non-animal. |

||

| Line 198: | Line 198: | ||

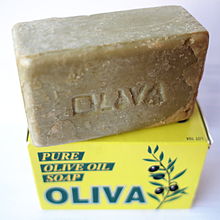

[[File:Oliiviöljysaippua.JPG|thumb|left|alt=photograph of vegan soap bar|[[Vegan soap]] made from [[olive oil]]; soap is usually made from [[tallow]] (animal fat).]] |

[[File:Oliiviöljysaippua.JPG|thumb|left|alt=photograph of vegan soap bar|[[Vegan soap]] made from [[olive oil]]; soap is usually made from [[tallow]] (animal fat).]] |

||

Vegans replace [[personal care]] products and [[household cleaner]]s containing animal products with products that are vegan |

Vegans replace [[personal care]] products and [[household cleaner]]s containing animal products with products that are vegan. Animal ingredients are ubiquitous because they are relatively inexpensive. After animals are slaughtered for meat, the leftovers are put through a [[Rendering (animals)|rendering]] process and some of that material, particularly the fat, is used in toiletries. |

||

Common animal-derived ingredients include: [[tallow]] in soap; [[collagen]]-derived [[glycerine]], which used as a lubricant and [[humectant]] in many haircare products, moisturizers, shaving foams, soaps and toothpastes;<ref name=toiletries/> [[lanolin]] from sheep's wool is often found in lip balm and moisturizers; [[stearic acid]] is a common ingredient in face creams, shaving foam and shampoos, (as with glycerine, it can be plant-based, but is usually animal-derived); [[Lactic acid]], an [[alpha-hydroxy acid]] derived from animal milk, is used in moisturizers; [[allantoin]]— from the [[comfrey]] plant or cows' urine —is found in shampoos, moisturizers and toothpaste;<ref name=toiletries>''Animal Ingredients A to Z'', E. G. Smith Collective, 2004, 3rd edition; Lars Thomsen and Reuben Proctor, ''Veganissimo A to Z'', The Experiment, 2013 (first published in Germany, 1996).{{pb}}{{Cite web|url=https://www.peta.org/living/food/animal-ingredients-list/|title=Animal-Derived Ingredients Resource|date=18 April 2012|publisher=[[PETA]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180315020126/https://www.peta.org/living/food/animal-ingredients-list/|archive-date=15 March 2018|url-status=live|access-date=14 March 2018}}</ref> and [[carmine]] from [[scale insect]]s, such as the female [[cochineal]], is used in food and cosmetics to produce red and pink shades;<ref>{{Cite news|last=Mestel|first=Rosie|date=20 April 2012|title=Cochineal and Starbucks: Actually, this dye is everywhere|url=https://articles.latimes.com/2012/apr/20/news/la-heb-cochineal-starbucks-20120420|url-status=dead|work=[[Los Angeles Times]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161206021847/https://articles.latimes.com/2012/apr/20/news/la-heb-cochineal-starbucks-20120420|archive-date=6 December 2016|access-date=14 March 2018}}</ref><ref>Raymond Eller Kirk, Donald Frederick Othmer, ''Kirk-Othmer Chemical Technology of Cosmetics'', John Wiley & Sons, 2012, 535.</ref> |

Common animal-derived ingredients include: [[tallow]] in soap; [[collagen]]-derived [[glycerine]], which used as a lubricant and [[humectant]] in many haircare products, moisturizers, shaving foams, soaps and toothpastes;<ref name=toiletries/> [[lanolin]] from sheep's wool is often found in lip balm and moisturizers; [[stearic acid]] is a common ingredient in face creams, shaving foam and shampoos, (as with glycerine, it can be plant-based, but is usually animal-derived); [[Lactic acid]], an [[alpha-hydroxy acid]] derived from animal milk, is used in moisturizers; [[allantoin]]— from the [[comfrey]] plant or cows' urine —is found in shampoos, moisturizers and toothpaste;<ref name=toiletries>''Animal Ingredients A to Z'', E. G. Smith Collective, 2004, 3rd edition; Lars Thomsen and Reuben Proctor, ''Veganissimo A to Z'', The Experiment, 2013 (first published in Germany, 1996).{{pb}}{{Cite web|url=https://www.peta.org/living/food/animal-ingredients-list/|title=Animal-Derived Ingredients Resource|date=18 April 2012|publisher=[[PETA]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180315020126/https://www.peta.org/living/food/animal-ingredients-list/|archive-date=15 March 2018|url-status=live|access-date=14 March 2018}}</ref> and [[carmine]] from [[scale insect]]s, such as the female [[cochineal]], is used in food and cosmetics to produce red and pink shades;<ref>{{Cite news|last=Mestel|first=Rosie|date=20 April 2012|title=Cochineal and Starbucks: Actually, this dye is everywhere|url=https://articles.latimes.com/2012/apr/20/news/la-heb-cochineal-starbucks-20120420|url-status=dead|work=[[Los Angeles Times]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161206021847/https://articles.latimes.com/2012/apr/20/news/la-heb-cochineal-starbucks-20120420|archive-date=6 December 2016|access-date=14 March 2018}}</ref><ref>Raymond Eller Kirk, Donald Frederick Othmer, ''Kirk-Othmer Chemical Technology of Cosmetics'', John Wiley & Sons, 2012, 535.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 04:33, 22 May 2021

| Veganism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Description | Elimination of the use of animal products, particularly in diet |

| Earliest proponents |

|

| Term coined by | Dorothy Morgan and Donald Watson (November 1944)[3][4] |

| Notable vegans | List of vegans |

| Notable publications | List of vegan media |

Veganism is the practice of abstaining from the use of animal products, particularly in diet, and an associated philosophy that rejects the commodity status of animals.[c] An individual who follows the diet or philosophy is known as a vegan. Distinctions may be made between several categories of veganism. Dietary vegans, also known as "strict vegetarians", refrain from consuming meat, eggs, dairy products, and any other animal-derived substances.[d] An ethical vegan, also known as a "moral vegetarian", is someone who not only follows a vegan diet but extends the philosophy into other areas of their lives, and opposes the use of animals for any purpose.[e] Another term is "environmental veganism", which refers to the avoidance of animal products on the premise that the industrial farming of animals is environmentally damaging and unsustainable.[22]

Well-planned vegan diets are regarded as appropriate for all stages of life, including infancy and pregnancy, by the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics,[f] the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council,[24] the British Dietetic Association,[25] Dietitians of Canada,[26] and the New Zealand Ministry of Health.[27] The German Society for Nutrition—which is a non-profit organisation and not an official health agency—does not recommend vegan diets for children or adolescents, or during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[g] There is inconsistent evidence for vegan diets providing a protective effect against metabolic syndrome, but some evidence suggests that a vegan diet can help with weight loss, especially in the short term.[29][30] Vegan diets tend to be higher in dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, iron, and phytochemicals, and lower in dietary energy, saturated fat, cholesterol, omega-3 fatty acid, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12.[h] A poorly-planned vegan diet may lead to nutritional deficiencies that nullify any beneficial effects and may cause serious health issues,[31][32][33] some of which can only be prevented with fortified foods or dietary supplements.[31][34] Vitamin B12 supplementation is important because its deficiency causes blood disorders and potentially irreversible neurological damage, though this danger is also present in poorly-planned non-vegan diets.[33][35][36]

Dorothy Morgan and Donald Watson coined the term "vegan" in 1944 when they co-founded the Vegan Society in the UK.[3][4][37] At first, they used it to mean "non-dairy vegetarian."[38][39] However, by May 1945, vegans explicitly abstained from "eggs, honey; and animals' milk, butter and cheese". From 1951, the Society defined it as "the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals".[40] Interest in veganism increased in the 2010s,[41][42] especially in the latter half.[42] More vegan stores opened, and vegan options became increasingly available in supermarkets and restaurants.

Origins

| Part of a series on |

| Veganism |

|---|

|

Groups |

|

Ideas |

|

Related |

Vegetarian etymology

The term "vegetarian" has been in use since around 1839 to refer to what was previously described as a vegetable regimen or diet.[43] Its origin is an irregular compound of vegetable[44] and the suffix -arian (in the sense of "supporter, believer" as in humanitarian).[45] The earliest known written use is attributed to actress, writer and abolitionist Fanny Kemble, in her Journal of a Residence on a Georgian plantation in 1838–1839.[i]

History

Vegetarianism can be traced to Indus Valley Civilization in 3300–1300 BCE in the Indian subcontinent,[48][49][50] particularly in northern and western ancient India.[51] Early vegetarians included Indian philosophers such as Mahavira, Acharya Kundakunda, and the Tamil poet Valluvar; the Indian emperors Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka; Greek philosophers such as Empedocles, Theophrastus, Plutarch, Plotinus, and Porphyry; and the Roman poet Ovid and the playwright Seneca the Younger.[52][53] The Greek sage Pythagoras may have advocated an early form of strict vegetarianism,[54][55] but his life is so obscure that it is disputed whether he ever advocated any form of vegetarianism at all.[56] He almost certainly prohibited his followers from eating beans[56] and from wearing woolen garments.[56] Eudoxus of Cnidus, a student of Archytas and Plato, writes that "Pythagoras was distinguished by such purity and so avoided killing and killers that he not only abstained from animal foods, but even kept his distance from cooks and hunters".[56] One of the earliest known vegans was the Arab poet al-Maʿarri (c. 973 – c. 1057).[b][57] Their arguments were based on health, the transmigration of souls, animal welfare, and the view—espoused by Porphyry in De Abstinentia ab Esu Animalium ("On Abstinence from Animal Food", c. 268 – c. 270)—that if humans deserve justice, then so do animals.[52]

Vegetarianism established itself as a significant movement in 19th-century Britain and the United States.[58] A minority of vegetarians avoided animal food entirely.[59] In 1813, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley published A Vindication of Natural Diet, advocating "abstinence from animal food and spirituous liquors", and in 1815, William Lambe, a London physician, stated that his "water and vegetable diet" could cure anything from tuberculosis to acne.[60] Lambe called animal food a "habitual irritation", and argued that "milk eating and flesh-eating are but branches of a common system and they must stand or fall together".[61] Sylvester Graham's meatless Graham diet—mostly fruit, vegetables, water, and bread made at home with stoneground flour—became popular as a health remedy in the 1830s in the United States.[62] Several vegan communities were established around this time. In Massachusetts, Amos Bronson Alcott, father of the novelist Louisa May Alcott, opened the Temple School in 1834 and Fruitlands in 1844,[63][j] and in England, James Pierrepont Greaves founded the Concordium, a vegan community at Alcott House on Ham Common, in 1838.[10][65]

Vegetarian Society

In 1843, members of Alcott House created the British and Foreign Society for the Promotion of Humanity and Abstinence from Animal Food,[67] led by Sophia Chichester, a wealthy benefactor of Alcott House.[68] Alcott House also helped to establish the UK Vegetarian Society, which held its first meeting in 1847 in Ramsgate, Kent.[69] The Medical Times and Gazette in London reported in 1884:

There are two kinds of Vegetarians—one an extreme form, the members of which eat no animal food products what-so-ever; and a less extreme sect, who do not object to eggs, milk, or fish. The Vegetarian Society ... belongs to the latter more moderate division.[59]

An article in the Society's magazine, the Vegetarian Messenger, in 1851 discussed alternatives to shoe leather, which suggests the presence of vegans within the membership who rejected animal use entirely, not only in diet.[70] By the 1886 publication of Henry S. Salt's A Plea for Vegetarianism and Other Essays, he asserts that, "It is quite true that most—not all—Food Reformers admit into their diet such animal food as milk, butter, cheese, and eggs..."[71] Russell Thacher Trall's The Hygeian Home Cook-Book published in 1874 is the first known vegan cookbook in America.[72] The book contains recipes "without the employment of milk, sugar, salt, yeast, acids, alkalies, grease, or condiments of any kind."[72] An early vegan cookbook, Rupert H. Wheldon's No Animal Food: Two Essays and 100 Recipes, was published by C. W. Daniel in 1910.[73] The consumption of milk and eggs became a battleground over the following decades. There were regular discussions about it in the Vegetarian Messenger; it appears from the correspondence pages that many opponents of veganism came from vegetarians.[73][74]

During a visit to London in 1931, Mahatma Gandhi—who had joined the Vegetarian Society's executive committee when he lived in London from 1888 to 1891—gave a speech to the Society arguing that it ought to promote a meat-free diet as a matter of morality, not health.[66][75] Lacto-vegetarians acknowledged the ethical consistency of the vegan position but regarded a vegan diet as impracticable and were concerned that it might be an impediment to spreading vegetarianism if vegans found themselves unable to participate in social circles where no non-animal food was available. This became the predominant view of the Vegetarian Society, which in 1935 stated: "The lacto-vegetarians, on the whole, do not defend the practice of consuming the dairy products except on the ground of expediency."[73]

Vegan etymology (1944)

The Vegan News

first edition, 1944

Donald Watson

front row, fourth left, 1947[76]

In August 1944, several members of the Vegetarian Society asked that a section of its newsletter be devoted to non-dairy vegetarianism. When the request was turned down, Donald Watson, secretary of the Leicester branch, set up a new quarterly newsletter in November 1944, priced tuppence.[12] He called it The Vegan News. The word vegan was invented by Watson and Dorothy Morgan, a schoolteacher he would later marry.[3][37] The word is based on "the first three and last two letters of 'vegetarian'" because it marked, in Mr Watson's words, "the beginning and end of vegetarian".[12][77] The Vegan News asked its readers if they could think of anything better than vegan to stand for "non-dairy vegetarian". They suggested allvega, neo-vegetarian, dairyban, vitan, benevore, sanivores, and beaumangeur.[12][78]

The first edition attracted more than 100 letters, including from George Bernard Shaw, who resolved to give up eggs and dairy.[74] The new Vegan Society held its first meeting in early November at the Attic Club, 144 High Holborn, London. Those in attendance were Donald Watson, Elsie B. Shrigley, Fay K. Henderson, Alfred Hy Haffenden, Paul Spencer and Bernard Drake, with Mme Pataleewa (Barbara Moore, a Russian-British engineer) observing.[79] World Vegan Day is held every 1 November to mark the founding of the Society and the month of November is considered by the Society to be World Vegan Month.[80]

The Vegan News changed its name to The Vegan in November 1945, by which time it had 500 subscribers.[81] It published recipes and a "vegan trade list" of animal-free products, such as toothpastes, shoe polishes, stationery and glue.[82] Vegan books appeared, including Vegan Recipes by Fay K. Henderson (1946) [83][84] and Aids to a Vegan Diet for Children by Kathleen V. Mayo (1948).[85][86]

The Vegan Society soon made clear that it rejected the use of animals for any purpose, not only in diet. In 1947, Watson wrote: "The vegan renounces it as superstitious that human life depends upon the exploitation of these creatures whose feelings are much the same as our own ...".[87] From 1948, The Vegan's front page read: "Advocating living without exploitation", and in 1951, the Society published its definition of veganism as "the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals".[87][88] In 1956, its vice-president, Leslie Cross, founded the Plantmilk Society; and in 1965, as Plantmilk Ltd and later Plamil Foods, it began production of one of the first widely distributed soy milks in the Western world.[89]

The first vegan society in the United States was founded in 1948 by Catherine Nimmo and Rubin Abramowitz in California, who distributed Watson's newsletter.[90][91] In 1960, H. Jay Dinshah founded the American Vegan Society (AVS), linking veganism to the concept of ahimsa, "non-harming" in Sanskrit.[91][92][93] According to Joanne Stepaniak, the word vegan was first published independently in 1962 by the Oxford Illustrated Dictionary, defined as "a vegetarian who eats no butter, eggs, cheese, or milk".[94]

Increasing interest

Alternative food movements

In the 1960s and 1970s, a vegetarian food movement emerged as part of the counterculture in the United States that focused on concerns about diet, the environment, and a distrust of food producers, leading to increasing interest in organic gardening.[95][96] One of the most influential vegetarian books of that time was Frances Moore Lappé's 1971 text, Diet for a Small Planet.[97] It sold more than three million copies and suggested "getting off the top of the food chain".[98]

The following decades saw research by a group of scientists and doctors in the United States, including physicians Dean Ornish, Caldwell Esselstyn, Neal D. Barnard, John A. McDougall, Michael Greger, and biochemist T. Colin Campbell, who argued that diets based on animal fat and animal protein, such as the Western pattern diet, were detrimental to health.[99] They produced a series of books that recommend vegan or vegetarian diets, including McDougall's The McDougall Plan (1983), John Robbins's Diet for a New America (1987), which associated meat eating with environmental damage, and Dr. Dean Ornish's Program for Reversing Heart Disease (1990).[100] In 2003 two major North American dietitians' associations indicated that well-planned vegan diets were suitable for all life stages.[101][102] This was followed by the film Earthlings (2005), Campbell's The China Study (2005), Rory Freedman and Kim Barnouin's Skinny Bitch (2005), Jonathan Safran Foer's Eating Animals (2009), and the film Forks over Knives (2011).[103]

In the 1980s, veganism became associated with punk subculture and ideologies, particularly straight edge hardcore punk in the United States;[104] and anarcho-punk in the United Kingdom.[105] This association continues on into the 21st century, as evinced by the prominence of vegan punk events such as Fluff Fest in Europe.[106][107]

Into the mainstream

The vegan diet became increasingly mainstream in the 2010s,[41][42][108] especially in the latter half.[42][109] The Economist declared 2019 "the year of the vegan".[110] The European Commission was granted the right to adopt an implementing act on food information related to suitability of a food for vegetarians or vegans in article 36 of Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council.[111] Chain restaurants began marking vegan items on their menus and supermarkets improved their selection of vegan-processed food.[112]

The global mock-meat market increased by 18 percent between 2005 and 2010,[113] and in the United States by eight percent between 2012 and 2015, to $553 million a year.[114] The Vegetarian Butcher (De Vegetarische Slager), the first known vegetarian butcher shop, selling mock meats, opened in the Netherlands in 2010,[113][115] while America's first vegan butcher, the Herbivorous Butcher, opened in Minneapolis in 2016.[114][116] Since 2017, more than 12,500 chain restaurant locations have begun offering Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods products including Carl's Jr. outlets offering Beyond Burgers and Burger King outlets serving Impossible Whoppers. Plant-based meat sales in the U.S have grown 37% in the past two years.[117]

In 2017, the United States School Nutrition Association found 14% of school districts across the country were serving vegan school meals compared to 11.5% of schools offering vegan lunch in 2016,[118] reflecting a change happening in many parts of the world including Brazil and England.

By 2016, 49% of Americans were drinking plant milk, and 91% still drank dairy milk.[119] In the United Kingdom, the plant milk market increased by 155 percent in two years, from 36 million litres (63 million imperial pints) in 2011 to 92 million (162 million imperial pints) in 2013.[120] There was a 185% increase in new vegan products between 2012 and 2016 in the UK.[109] In 2011, Europe's first vegan supermarkets appeared in Germany: Vegilicious in Dortmund and Veganz in Berlin.[121][122]

In 2017, veganism rose in popularity in Hong Kong and China, particularly among millennials.[123] China's vegan market is estimated to rise by more than 17% between 2015 and 2020,[123][124] which is expected to be "the fastest growth rate internationally in that period".[123] This exceeds the projected growth in the second and third fastest-growing vegan markets internationally in the same period, the United Arab Emirates (10.6%) and Australia (9.6%) respectively.[124][125] In total, as of 2016[update], the largest share of vegan consumers globally currently reside in Asia Pacific with nine percent of people following a vegan diet.[124] In 2013, the Oktoberfest in Munich — traditionally a meat-heavy event — offered vegan dishes for the first time in its 200-year history.[126]

In 2018, the book The End of Animal Farming by Jacy Reese Anthis argued that veganism will completely replace animal-based food by 2100.[127] The book was featured in The Guardian,[128] The New Republic,[129] and Forbes, among other newspapers and magazines.[130]

Veganuary is a UK based non-profit organization that educates and encourages people around the world to try a vegan diet for the month of January. Veganuary also refers to the month-long challenge itself. On February 1, 2021, Veganuary released the final figures of their 2021 campaign to reveal record-breaking results. In January 2021, 582,538 people from 209 different countries and territories signed up for the 31-day vegan challenge, exceeding the total of 400,000 who took part in 2020.[131] In December 2020, public figures including Paul McCartney, Ricky Gervais, Jane Goodall, John Bishop, Sara Pascoe and over a hundred more celebrities, politicians, businesses and NGOs signed a joint letter calling on people to join the fight against climate change and prevent future pandemics through changing to a plant-based diet, starting with signing-up for Veganuary.[132]

In 2021, ONA, a restaurant near Bordeaux in France, was the first vegan restaurant to receive a Michelin star.[133]

Veganism by country

Australia: Australians topped Google's worldwide searches for the word "vegan" between mid-2015 and mid-2016.[134] A Euromonitor International study concluded the market for packaged vegan food in Australia would rise 9.6% per year between 2015 and 2020, making Australia the third-fastest growing vegan market behind China and the United Arab Emirates.[124][125]

Australia: Australians topped Google's worldwide searches for the word "vegan" between mid-2015 and mid-2016.[134] A Euromonitor International study concluded the market for packaged vegan food in Australia would rise 9.6% per year between 2015 and 2020, making Australia the third-fastest growing vegan market behind China and the United Arab Emirates.[124][125] Austria: In 2013, Kurier estimated that 0.5 percent of Austrians practised veganism, and in the capital, Vienna, 0.7 percent.[135]

Austria: In 2013, Kurier estimated that 0.5 percent of Austrians practised veganism, and in the capital, Vienna, 0.7 percent.[135] Belgium: A 2016 iVOX online study found that out of 1000 Dutch-speaking residents of Flanders and Brussels of 18 years and over, 0.3 percent were vegan.[136]

Belgium: A 2016 iVOX online study found that out of 1000 Dutch-speaking residents of Flanders and Brussels of 18 years and over, 0.3 percent were vegan.[136] Brazil: According to a research by IBOPE Inteligência published in April 2018, 14% of the Brazilians, or about 30 million people, considered themselves vegetarians, where 7 million of these were vegans.[137][138]

Brazil: According to a research by IBOPE Inteligência published in April 2018, 14% of the Brazilians, or about 30 million people, considered themselves vegetarians, where 7 million of these were vegans.[137][138] Canada: In 2018, one survey estimated that 2.1 percent of adult Canadians considered themselves as vegans.[139]

Canada: In 2018, one survey estimated that 2.1 percent of adult Canadians considered themselves as vegans.[139] Germany: As of 2016[update], data estimated that people following a vegan diet in Germany varied between 0.1% and 1% of the population (between 81,000 and 810,000 persons).[28]

Germany: As of 2016[update], data estimated that people following a vegan diet in Germany varied between 0.1% and 1% of the population (between 81,000 and 810,000 persons).[28] India: In the 2005–06 National Health Survey, 1.6% of the surveyed population reported never consuming animal products. Veganism was most common in the states of Gujarat (4.9%) and Maharashtra (4.0%).[140]

India: In the 2005–06 National Health Survey, 1.6% of the surveyed population reported never consuming animal products. Veganism was most common in the states of Gujarat (4.9%) and Maharashtra (4.0%).[140] Israel: Five percent (approx. 300,000) in Israel said they were vegan in 2014, making it the highest per capita vegan population in the world.[141] A 2015 survey by Globes and Israel's Channel 2 News similarly found 5% of Israelis were vegan.[142] Veganism increased among Israeli Arabs.[143] The Israeli army made special provision for vegan soldiers in 2015, which included providing non-leather boots and wool-free berets.[144] Veganism also simplifies adherence to the Judaic prohibition on combining meat and milk in meals.

Israel: Five percent (approx. 300,000) in Israel said they were vegan in 2014, making it the highest per capita vegan population in the world.[141] A 2015 survey by Globes and Israel's Channel 2 News similarly found 5% of Israelis were vegan.[142] Veganism increased among Israeli Arabs.[143] The Israeli army made special provision for vegan soldiers in 2015, which included providing non-leather boots and wool-free berets.[144] Veganism also simplifies adherence to the Judaic prohibition on combining meat and milk in meals. Italy: Between 0.6 and three percent of Italians were reported to be vegan as of 2015[update].[145]

Italy: Between 0.6 and three percent of Italians were reported to be vegan as of 2015[update].[145] Netherlands: In 2018, the Dutch Society for Veganism (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Veganisme, NVV) estimated there were more than 100,000 Dutch vegans (0.59 percent), based on their membership growth.[146] In July 2020 the NVV estimated the number of vegans in the Netherlands at 150,000. That is approximately 0.9% of the Dutch population.[147]

Netherlands: In 2018, the Dutch Society for Veganism (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Veganisme, NVV) estimated there were more than 100,000 Dutch vegans (0.59 percent), based on their membership growth.[146] In July 2020 the NVV estimated the number of vegans in the Netherlands at 150,000. That is approximately 0.9% of the Dutch population.[147] Romania: Followers of the Romanian Orthodox Church keep fast during several periods throughout the ecclesiastical calendar amounting to a majority of the year. In the Romanian Orthodox tradition, devotees abstain from eating any animal products during these times. As a result, vegan foods are abundant in stores and restaurants; however, Romanians may not be familiar with a vegan diet as a full-time lifestyle choice.[148]

Romania: Followers of the Romanian Orthodox Church keep fast during several periods throughout the ecclesiastical calendar amounting to a majority of the year. In the Romanian Orthodox tradition, devotees abstain from eating any animal products during these times. As a result, vegan foods are abundant in stores and restaurants; however, Romanians may not be familiar with a vegan diet as a full-time lifestyle choice.[148] Sweden: Four percent said they were vegan in a 2014 Demoskop poll.[149]

Sweden: Four percent said they were vegan in a 2014 Demoskop poll.[149] Switzerland: Market research company DemoSCOPE estimated in 2017 that three percent of the population was vegan.[150]

Switzerland: Market research company DemoSCOPE estimated in 2017 that three percent of the population was vegan.[150] United Kingdom: In the UK, where the tofu and mock-meats market was worth £786.5 million in 2012, two percent said they were vegan in a 2007 government survey.[151] A 2016 Ipsos MORI study commissioned by the Vegan Society, surveying almost 10,000 people aged 15 or over across England, Scotland, and Wales, found that 1.05 percent were vegan; the Vegan Society estimates that 542,000 in the UK follow a vegan diet.[152] According to a 2018 survey by Comparethemarket.com, the number of people who identify as vegans in the United Kingdom has risen to over 3.5 million, which is approximately seven percent of the population, and environmental concerns were a major factor in this development.[153] However, doubt was cast on this inflated figure by the UK-based Vegan Society, who perform their own regular survey: the Vegan Society themselves found in 2018 that there were 600,000 vegans in Great Britain (1.16%), which was seen as a dramatic increase on previous figures.[154][155] In 2020, a court ruled that ethical veganism was a protected belief under the Equality Act 2010, meaning employers cannot discriminate against vegans.[156]

United Kingdom: In the UK, where the tofu and mock-meats market was worth £786.5 million in 2012, two percent said they were vegan in a 2007 government survey.[151] A 2016 Ipsos MORI study commissioned by the Vegan Society, surveying almost 10,000 people aged 15 or over across England, Scotland, and Wales, found that 1.05 percent were vegan; the Vegan Society estimates that 542,000 in the UK follow a vegan diet.[152] According to a 2018 survey by Comparethemarket.com, the number of people who identify as vegans in the United Kingdom has risen to over 3.5 million, which is approximately seven percent of the population, and environmental concerns were a major factor in this development.[153] However, doubt was cast on this inflated figure by the UK-based Vegan Society, who perform their own regular survey: the Vegan Society themselves found in 2018 that there were 600,000 vegans in Great Britain (1.16%), which was seen as a dramatic increase on previous figures.[154][155] In 2020, a court ruled that ethical veganism was a protected belief under the Equality Act 2010, meaning employers cannot discriminate against vegans.[156] United States: Estimates of vegans in the U.S. in past varied from 2% (Gallup, 2012)[157] to 0.5% (Faunalytics, 2014). According to the latter, 70% of those who adopted a vegan diet abandoned it.[158] However, Top Trends in Prepared Foods 2017, a report by GlobalData, estimated that "6% of US consumers now claim to be vegan, up from just 1% in 2014."[159] In 2020 YouGov published the results of their 2019 research; results showed only 2.26% reported being vegan. Nearly 59% of the vegan respondents were female.[160] According to the BBC, black Americans are almost three times more likely to be vegan and vegetarian than all other Americans. They cited a study by Pew Research center which claims that 8% of black Americans are strict vegans and vegetarians, compared to 3% of the general public.[161]

United States: Estimates of vegans in the U.S. in past varied from 2% (Gallup, 2012)[157] to 0.5% (Faunalytics, 2014). According to the latter, 70% of those who adopted a vegan diet abandoned it.[158] However, Top Trends in Prepared Foods 2017, a report by GlobalData, estimated that "6% of US consumers now claim to be vegan, up from just 1% in 2014."[159] In 2020 YouGov published the results of their 2019 research; results showed only 2.26% reported being vegan. Nearly 59% of the vegan respondents were female.[160] According to the BBC, black Americans are almost three times more likely to be vegan and vegetarian than all other Americans. They cited a study by Pew Research center which claims that 8% of black Americans are strict vegans and vegetarians, compared to 3% of the general public.[161]

Animal products

General

Vegan Society sunflower:

certified vegan, no animal testing

PETA bunny:

certified vegan, no animal testing

Leaping bunny:

no animal testing, might not be vegan

While vegans broadly abstain from animal products, there are many ways in which animal products are used, and different individuals and organizations that identify with the practice of veganism may use some limited animal products based on philosophy, means or other concerns. Philosopher Gary Steiner argues that it is not possible to be entirely vegan, because animal use and products are "deeply and imperceptibly woven into the fabric of human society".[162]

Animal Ingredients A to Z (2004) and Veganissimo A to Z (2013) list which ingredients might be animal-derived. The British Vegan Society's sunflower logo and PETA's bunny logo mean the product is certified vegan, which includes no animal testing. The Leaping Bunny logo signals no animal testing, but it might not be vegan.[163][164] The Vegan Society criteria for vegan certification are that the product contain no animal products, and that neither the finished item nor its ingredients have been tested on animals by, or on behalf of, the manufacturer or by anyone over whom the manufacturer has control. Its website contains a list of certified products,[165][166] as does Australia's Choose Cruelty Free (CCF).[167] The British Vegan Society will certify a product only if it is free of animal involvement as far as possible and practical, including animal testing,[165][168][169] but "recognises that it is not always possible to make a choice that avoids the use of animals",[170] an issue that was highlighted in 2016 when it became known that the UK's newly introduced £5 note contained tallow.[171][172]

Meat, eggs and dairy

Like vegetarians vegans do not eat meat (including beef, pork, poultry, fowl, game, animal seafood). The main difference between a vegan and vegetarian diet is that vegans exclude dairy products and eggs. Ethical vegans avoid them on the premise that their production causes animal suffering and premature death. In egg production, most male chicks are culled because they do not lay eggs.[173] To obtain milk from dairy cattle, cows are made pregnant to induce lactation; they are kept lactating for three to seven years, then slaughtered. Female calves can be separated from their mothers within 24 hours of birth, and fed milk replacer to retain the cow's milk for human consumption. Most male calves are slaughtered at birth, sent for veal production, or reared for beef.[174][175]

Clothing

Many clothing products may be made of animal products such as silk, wool (including lambswool, shearling, cashmere, angora, mohair, and a number of other fine wools), fur, feathers, pearls, animal-derived dyes, leather, snakeskin, or other kinds of skin or animal product. While dietary vegans might use animal products in clothing, toiletries, and similar, ethical veganism extends not only to matters of food but also to the wearing or use of animal products, and rejects the commodification of animals altogether.[20]: 62 Most leather clothing is made from cow skins. Some vegans regard the purchase of leather, particularly from cows, as financial support for the meat industry.[176]: 115 Vegans may wear clothing items and accessories made of non-animal-derived materials such as hemp, linen, cotton, canvas, polyester, artificial leather (pleather), rubber, and vinyl.[176]: 16 Leather alternatives can come from materials such as cork, piña (from pineapples), cactus, and mushroom leather.[177][178][179] Some vegan clothes, in particular leather alternatives, are made of petroleum-based products, which has triggered criticism because of the environmental damage involved in their production.[180]

Toiletries

Vegans replace personal care products and household cleaners containing animal products with products that are vegan. Animal ingredients are ubiquitous because they are relatively inexpensive. After animals are slaughtered for meat, the leftovers are put through a rendering process and some of that material, particularly the fat, is used in toiletries.

Common animal-derived ingredients include: tallow in soap; collagen-derived glycerine, which used as a lubricant and humectant in many haircare products, moisturizers, shaving foams, soaps and toothpastes;[181] lanolin from sheep's wool is often found in lip balm and moisturizers; stearic acid is a common ingredient in face creams, shaving foam and shampoos, (as with glycerine, it can be plant-based, but is usually animal-derived); Lactic acid, an alpha-hydroxy acid derived from animal milk, is used in moisturizers; allantoin— from the comfrey plant or cows' urine —is found in shampoos, moisturizers and toothpaste;[181] and carmine from scale insects, such as the female cochineal, is used in food and cosmetics to produce red and pink shades;[182][183]

Beauty Without Cruelty, founded as a charity in 1959, was one of the earliest manufacturers and certifiers of animal-free personal care products.[184]

Insect products

Vegan groups disagree about insect products.[185] Neither the Vegan Society nor the American Vegan Society considers honey, silk, and other insect products as suitable for vegans.[169][186] Some vegans believe that exploiting the labor of bees and harvesting their energy source is immoral, and that commercial beekeeping operations can harm and even kill bees.[187] Insect products can be defined much more widely, as commercial bees are used to pollinate about 100 different food crops.[185]

Pet food

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (August 2020) |

This section may contain an excessive number of citations. The details given are: 5 sentences cited with 22 references (includes combination citations) is overkill. See also WP:POVPUSH. (August 2020) |

Due to the environmental impact of meat-based pet food[188][189] and the ethical problems it poses for vegans,[190][191][192][193][194][195] some vegans extend their philosophy to include the diets of pets.[189][196][197][198] This is particularly true for domesticated cats[199] and dogs,[200] for which vegan pet food is both available and nutritionally complete,[189][196][197] such as Vegepet. This practice has been met with caution and criticism,[196][201] especially regarding vegan cat diets because felids are obligate carnivores.[195][196][201] Nutritionally complete vegan pet diets are comparable to meat-based ones for cats and dogs.[202] A 2015 study found that 6 out of 24 commercial vegan pet food brands do not meet the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) labeling regulations for amino acid adequacy.[203]

Other products and farming practices

A concern is the case of medications, which are routinely tested on animals to ensure they are effective and safe,[204] and may also contain animal ingredients, such as lactose, gelatine, or stearates.[170] There may be no alternatives to prescribed medication or these alternatives may be unsuitable, less effective, or have more adverse side effects.[170] Experimentation with laboratory animals is also used for evaluating the safety of vaccines, food additives, cosmetics, household products, workplace chemicals, and many other substances.[205] Vegans may avoid certain vaccines, such as the flu vaccine, which is commonly produced in chicken eggs.[206] An effective alternative, Flublok, is widely available in the United States.[206]

Farming of fruits and vegetables may include fertilizing the soil with animal manure – even on organic farms,[207] possibly causing a concern to vegans for ethical or environmental reasons.[208] "Vegan" (or "animal-free") farming uses plant compost only.[208]

Vegan diet

Vegan cuisine at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

Vegan cuisine at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

Vegan diets are based on grains and other seeds, legumes (particularly beans), fruits, vegetables, edible mushrooms, and nuts.[209]

Soy

Meatless products made from soybeans (tofu), or wheat-based seitan are sources of plant protein, commonly in the form of vegetarian sausage, mince, and veggie burgers.[210] Soy-based dishes are common in vegan diets because soy is a protein source.[211] They are consumed most often in the form of soy milk and tofu (bean curd), which is soy milk mixed with a coagulant. Tofu comes in a variety of textures, depending on water content, from firm, medium firm and extra firm for stews and stir-fries to soft or silken for salad dressings, desserts and shakes. Soy is also eaten in the form of tempeh and textured vegetable protein (TVP); also known as textured soy protein (TSP), the latter is often used in pasta sauces.[211]

Plant milk and dairy product alternatives

| Nutritional content of cows', soy, and almond milk | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cows' milk (whole, vitamin D added)[212] |

Soy milk (unsweetened; fortified)[213] |

Silk almond milk (unsweetened original; fortified)[214] | |

| Dietary energy per 240 mL cup | 620 kJ (149 kcal) | 330 kJ (80 kcal) | 120 kJ (29 kcal) |

| Protein (g) | 7.69 | 6.95 | 1 |

| Fat (g) | 7.93 | 3.91 | 2.5 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 4.55 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 11.71 | 4.23 | 1 |

| Fibre (g) | 0 | 1.2 | 1 |

| Sugars (g) | 12.32 | 1 | 0 |

| Calcium (mg) | 276 | 301 | 451 |

| Potassium (mg) | 322 | 292 | 36 |

| Sodium (mg) | 105 | 90 | 170 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 1.10 | 2.70 | 3 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 395 | 503 | 499 |

| Vitamin D (IU) | 124 | 119 | 101 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 24 | 0 | 0 |

Plant milks—such as soy milk, almond milk, cashew milk, grain milks (oat milk, flax milk and rice milk), hemp milk, and coconut milk—are used in place of cows' or goats' milk.[l] Soy milk provides around 7 g (¼oz) of protein per cup (240 mL or 8 fl oz), compared with 8 g (2/7oz) of protein per cup of cow's milk. Almond milk is lower in dietary energy, carbohydrates, and protein.[216] Soy milk should not be used as a replacement for breast milk for babies. Babies who are not breastfed may be fed commercial infant formula, normally based on cows' milk or soy. The latter is known as soy-based infant formula or SBIF.[217][218]

Butter and margarine can be replaced with alternate vegan products.[219] Vegan cheeses are made from seeds, such as sesame and sunflower; nuts, such as cashew,[220] pine nut, and almond;[221] and soybeans, coconut oil, nutritional yeast, tapioca,[222] and rice, among other ingredients; and can replicate the meltability of dairy cheese.[223] Nutritional yeast is a common substitute for the taste of cheese in vegan recipes.[219] Cheese substitutes can be made at home, including from nuts, such as cashews.[220] Yoghurt and cream products can be replaced with plant-based products such as soy yoghurt.[224][225]

Various types of plant cream have been created to replace dairy cream, and some types of imitation whipped cream are non-dairy.

In the 2010s and 2020s, a number of companies have genetically engineered yeast to produce cow milk proteins, whey, or fat, without the use of cows. These include Perfect Day, Novacca, Motif FoodWorks, Remilk, Final Foods, Imagindairy, Nourish Ingredients, and Circe.[226]

Egg replacements

As of 2019 in the United States, there were numerous vegan egg substitutes available, including products used for "scrambled" eggs, cakes, cookies, and doughnuts.[227][228] Baking powder, silken (soft) tofu, mashed potato, bananas, flaxseeds, and aquafaba from chickpeas can also be used as egg substitutes.[219][228][229]

Raw veganism

Raw veganism, combining veganism and raw foodism, excludes all animal products and food cooked above 48 °C (118 °F). A raw vegan diet includes vegetables, fruits, nuts, grain and legume sprouts, seeds, and sea vegetables. There are many variations of the diet, including fruitarianism.[230]

Vegan nutrition

Health effects

The American Dietetic Association stated that "plant-based eating is recognized as not only nutritionally sufficient but also as a way to reduce the risk for many chronic illnesses".[231] Similarly, insurance group Kaiser Permanente,[232] the American Institute for Cancer Research[233] and the US-based Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics state that vegan diets may reduce the risk of certain health conditions, such as cancer.[234]

The reduction in cancer risk may stem from the fact that vegans do not eat processed meat or red meat.[235] In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization (WHO) classified processed meat (bacon, ham, hot dogs, sausages) as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1) and red meat as "probably carcinogenic" (Group 2A) to humans.[236]

There is inconsistent evidence for vegan diets providing a protective effect against metabolic syndrome.[29] Vegan diets appear to help weight loss, especially in the short term.[30] There is some tentative evidence of an association between vegan diets and a reduced risk of cancer.[237] A vegan diet offers no benefit over other types of healthy diet in helping with high blood pressure.[238]

However, eliminating all animal products increases the risk of deficiencies of vitamins B12 and D, calcium, and omega-3 fatty acids.[31] Vitamin B12 deficiency occurs in up to 80% of vegans that do not supplement with vitamin B12.[239] Vegans are at risk of low bone mineral density without supplements.[31][240] (see section Critical nutrients)

Positions of dietetic and government associations

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and Dietitians of Canada state that properly planned vegan diets are appropriate for all life stages, including pregnancy and lactation.[241] The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council similarly recognizes a well-planned vegan diet as viable for any age,[24][242] as does the New Zealand Ministry of Health,[243] British National Health Service,[244] British Nutrition Foundation,[245] Dietitians Association of Australia,[246] United States Department of Agriculture,[247] Mayo Clinic,[248] Canadian Pediatric Society,[249] and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.[250]

The German Society for Nutrition does not recommend a vegan diet for babies, children and adolescents, or for pregnancy or breastfeeding.[251]

Pregnancy, infants and children

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and Dietitians of Canada consider well-planned vegetarian and vegan diets "appropriate for individuals during all stages of the lifecycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and for athletes".[23] The German Society for Nutrition cautioned against a vegan diet for pregnant women, breastfeeding women, babies, children, and adolescents.[28] The position of the Canadian Pediatric Society is that "well-planned vegetarian and vegan diets with appropriate attention to specific nutrient components can provide a healthy alternative lifestyle at all stages of fetal, infant, child and adolescent growth. It is recommended that attention should be given to nutrient intake, particularly protein, vitamins B12 and D, essential fatty acids, iron, zinc, and calcium.[249]

Critical nutrients

The American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics states that special attention may be necessary to ensure that a vegan diet will provide adequate amounts of vitamin B12, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, iodine, iron, and zinc.[252] These nutrients are available in plant foods, with the exception of vitamin B12, which can be obtained only from B12-fortified vegan foods or supplements. Iodine may also require supplementation, such as using iodized salt.[252]

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is a bacterial product needed for cell division, the formation and maturation of red blood cells, the synthesis of DNA, and normal nerve function. A deficiency may cause megaloblastic anaemia and neurological damage, and, if untreated, may lead to death.[35][254][m] The high content of folacin in vegetarian diets may mask the hematological symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency, so it may go undetected until neurological signs in the late stages are evident, which can be irreversible, such as neuropsychiatric abnormalities, neuropathy, dementia and, occasionally, atrophy of the optic nerves.[23][33][256]

Vegans sometimes fail to obtain enough B12 from their diet because among non-fortified foods, only those of animal origin contain sufficient amounts.[33][256][n] Vegetarians are also at risk, as are older people and those with certain medical conditions.[258][259] A 2013 study found that "[v]egans should take preventive measures to ensure adequate intake of this vitamin, including regular consumption of supplements containing B12."[o]

Iodine

Iodine supplementation may be necessary for vegans in countries where salt is not typically iodized, where it is iodized at low levels, or where, as in Britain and Ireland, dairy products are relied upon for iodine delivery because of low levels in the soil.[261] Iodine can be obtained from most vegan multivitamins or regular consumption of seaweeds, such as kelp.[262]

Calcium

Calcium is needed to maintain bone health and for several metabolic functions, including muscle function, vascular contraction and vasodilation, nerve transmission, intracellular signalling, and hormonal secretion. Ninety-nine percent of the body's calcium is stored in the bones and teeth.[263][264][265]: 35–74 High-calcium foods may include fortified plant milk, kale, collards and raw garlic as common vegetable sources.[266]

A 2007 report based on the Oxford cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition, which began in 1993, suggested that vegans have an increased risk of bone fractures over meat eaters and vegetarians, likely because of lower dietary calcium intake. The study found that vegans consuming at least 525 mg of calcium daily have a risk of fractures similar to that of other groups.[p][269] A 2009 study found the bone mineral density (BMD) of vegans was 94 percent that of omnivores, but deemed the difference clinically insignificant.[270][q]

Protein

Varied intake of plant foods can meet human health needs for protein and amino acids.[234] The American Dietetic Association said in 2009 that a variety of plant foods consumed over the course of a day can provide all the essential amino acids for healthy adults, which means that protein combining in the same meal is generally not necessary.[272]

Foods high in protein in a vegan diet include legumes (such as beans and lentils), nuts, seeds, and grains (such as oats, wheat, and quinoa).[234][273]

Vitamin D

Vitamin D (calciferol) is needed for several functions, including calcium absorption, enabling mineralization of bone, and bone growth. Without it bones can become thin and brittle; together with calcium it offers protection against osteoporosis. Vitamin D is produced in the body when ultraviolet rays from the sun hit the skin; outdoor exposure is needed because UVB radiation does not penetrate glass. It is present in salmon, tuna, mackerel and cod liver oil, with small amounts in cheese, egg yolks, and beef liver, and in some mushrooms.[274]

Most vegan diets contain little or no vitamin D without fortified food. People with little sun exposure may need supplements. The extent to which sun exposure is sufficient depends on the season, time of day, cloud and smog cover, skin melanin content, and whether sunscreen is worn. According to the National Institutes of Health, most people can obtain and store sufficient vitamin D from sunlight in the spring, summer, and fall, even in the far north. They report that some researchers recommend 5–30 minutes of sun exposure without sunscreen between 10 am and 3 pm, at least twice a week. Tanning beds emitting 2–6% UVB radiation have a similar effect, though tanning is inadvisable.[274][275]

Iron

Due to the lower bioavailability of iron from plant sources, the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences established a separate RDA for vegetarians and vegans of 14 mg (¼gr) for vegetarian men and postmenopausal women, and 33 mg (½gr) for premenopausal women not using oral contraceptives.[277]

High-iron vegan foods include soybeans, blackstrap molasses, black beans, lentils, chickpeas, spinach, tempeh, tofu, and lima beans.[278][279] Iron absorption can be enhanced by eating a source of vitamin C at the same time,[280] such as half a cup of cauliflower or five fluid ounces of orange juice. Coffee and some herbal teas can inhibit iron absorption, as can spices that contain tannins such as turmeric, coriander, chiles, and tamarind.[279]

Omega-3 fatty acids

Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), an omega-3 fatty acid, is found in walnuts, seeds, and vegetable oils, such as canola and flaxseed oil.[281] EPA and DHA, the other primary omega-3 fatty acids, are found only in animal products and algae.[282]

Philosophy

Ethical veganism

Ethical veganism, also known as moral vegetarianism, is based on opposition to speciesism, the assignment of value to individuals on the basis of (animal) species membership alone. Divisions within animal rights theory include the utilitarian, protectionist approach, which pursues improved conditions for animals. It also pertains to the rights-based abolitionism, which seeks to end human ownership of non-humans, including as pets. Abolitionists argue that protectionism serves only to make the public feel that animal use can be morally unproblematic (the "happy meat" position).[20]: 62–63

Donald Watson, co-founder of The Vegan Society, stated in response to a question on why he was an ethical vegan, "If an open-minded, honest person pursues a course long enough, and listens to all the criticisms, and in one's own mind can satisfactorily meet all the criticisms against that idea, sooner or later one's resistance against what one sees as evil tradition has to be discarded."[283] On bloodsports, he has said that "to kill creatures for fun must be the very dregs," and that vivisection and animal experimentation "is probably the cruelest of all Man's attack on the rest of Creation." He has also stated that "vegetarianism, whilst being a necessary stepping-stone, between meat eating and veganism, is only a stepping stone."[283]

Alex Hershaft, co-founder of the Farm Animal Rights Movement and Holocaust survivor, states he "was always bothered by the idea of hitting a beautiful, living, innocent animal over the head, cutting him up into pieces, then shoving the pieces into [his] mouth," and that his experiences in the Nazi Holocaust allowed him "to empathize with the conditions of animals in factory farms, auction yards, and slaughterhouses" because he "knows firsthand what it's like to be treated like a worthless object."[284]

Law professor Gary Francione, an abolitionist, argues that all sentient beings should have the right not to be treated as property, and that adopting veganism must be the baseline for anyone who believes that non-humans have intrinsic moral value.[r][20]: 62 Philosopher Tom Regan, also a rights theorist, argues that animals possess value as "subjects-of-a-life", because they have beliefs, desires, memory and the ability to initiate action in pursuit of goals. The right of subjects-of-a-life not to be harmed can be overridden by other moral principles, but Regan argues that pleasure, convenience and the economic interests of farmers are not weighty enough.[286] Philosopher Peter Singer, a protectionist and utilitarian, argues that there is no moral or logical justification for failing to count animal suffering as a consequence when making decisions, and that killing animals should be rejected unless necessary for survival.[287] Despite this, he writes that "ethical thinking can be sensitive to circumstances", and that he is "not too concerned about trivial infractions".[288]

An argument proposed by Bruce Friedrich, also a protectionist, holds that strict adherence to veganism harms animals, because it focuses on personal purity, rather than encouraging people to give up whatever animal products they can.[289] For Francione, this is similar to arguing that, because human-rights abuses can never be eliminated, we should not defend human rights in situations we control. By failing to ask a server whether something contains animal products, we reinforce that the moral rights of animals are a matter of convenience, he argues. He concludes from this that the protectionist position fails on its own consequentialist terms.[20]: 72–73

Philosopher Val Plumwood maintained that ethical veganism is "subtly human-centred", an example of what she called "human/nature dualism" because it views humanity as separate from the rest of nature. Ethical vegans want to admit non-humans into the category that deserves special protection, rather than recognize the "ecological embeddedness" of all.[290] Plumwood wrote that animal food may be an "unnecessary evil" from the perspective of the consumer who "draws on the whole planet for nutritional needs"—and she strongly opposed factory farming—but for anyone relying on a much smaller ecosystem, it is very difficult or impossible to be vegan.[291]

Bioethicist Ben Mepham,[292] in his review of Francione and Garner's book The Animal Rights Debate: Abolition or Regulation?, concludes that "if the aim of ethics is to choose the right, or best, course of action in specific circumstances 'all things considered', it is arguable that adherence to such an absolutist agenda is simplistic and open to serious self-contradictions. Or, as Farlie puts it, with characteristic panache: 'to conclude that veganism is the "only ethical response" is to take a big leap into a very muddy pond'."[293] He cites as examples the adverse effects on animal wildlife derived from the agricultural practices necessary to sustain most vegan diets and the ethical contradiction of favoring the welfare of domesticated animals but not that of wild animals; the imbalance between the resources that are used to promote the welfare of animals as opposed to those destined to alleviate the suffering of the approximately one billion human beings who undergo malnutrition, abuse, and exploitation; the focus on attitudes and conditions in western developed countries, leaving out the rights and interests of societies whose economy, culture and, in some cases, survival rely on a symbiotic relationship with animals.[293]

David Pearce, a transhumanist philosopher, has argued that humanity has a "hedonistic imperative" to not merely avoid cruelty to animals or abolish the ownership of non-human animals, but also to redesign the global ecosystem such that wild animal suffering ceases to exist.[294] In the pursuit of abolishing suffering itself, Pearce promotes predation elimination among animals and the "cross-species global analogue of the welfare state". Fertility regulation could maintain herbivore populations at sustainable levels, "a more civilised and compassionate policy option than famine, predation, and disease".[295] The increasing number of vegans and vegetarians in the transhumanism movement has been attributed in part to Pearce's influence.[296]

A growing political philosophy that incorporates veganism as part of its revolutionary praxis is veganarchism, which seeks "total abolition" or "total liberation" for all animals, including humans. Veganarchists identify the state as unnecessary and harmful to animals, both human and non-human, and advocate for the adoption of a vegan lifestyle within a stateless society. The term was popularized in 1995 with Brian A. Dominick's pamphlet Animal Liberation and Social Revolution, described as "a vegan perspective on anarchism or an anarchist perspective on veganism".[297]

Direct action is a common practice among veganarchists (and anarchists generally) with groups like the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), the Animal Rights Militia (ARM), the Justice Department (JD) and Revolutionary Cells – Animal Liberation Brigade (RCALB) often engaging in such activities, sometimes criminally, to further their goals.[298] Steven Best, animal rights activist and professor of philosophy at the University of Texas at El Paso, is an advocate of this approach, and has been critical of vegan activists like Francione for supporting animal liberation, but not total liberation, which would include not only opposition to "the property status of animals", but also "a serious critique of capitalism, the state, property relations, and commodification dynamics in general." In particular, he criticizes the focus on the simplistic and apolitical "Go Vegan" message directed mainly at wealthy Western audiences, while ignoring people of color, the working class and the poor, especially in the developing world, noting that "for every person who becomes vegan, a thousand flesh eaters arise in China, India and Indonesia." The "faith in the singular efficacy of conjectural education and moral persuasion," Best writes, is no substitute for "direct action, mass confrontation, civil disobedience, alliance politics, and struggle for radical change."[299] Donald Watson has stated that he "respects the people enormously who do it, believing that it's the most direct and quick way to achieve their ends."[283]

Some vegans also embrace the philosophy of anti-natalism, as they see the two as complementary in terms of "harm reduction" to animals and the environment.[300]

Vegan social psychologist Melanie Joy described the ideology in which people support the use and consumption of animal products as carnism,[301] as a sort of opposite to veganism.[302]

Exploitation concerns

The Vegan Society has written, "by extension, [veganism] promotes the development and use of animal-free alternatives for the benefit of humans."[303] Many ethical vegans and vegan organizations cite the poor working conditions of slaughterhouse workers as a reason to reject animal products.[304] The first vegan activist, Donald Watson, has stated, "If these butchers and vivisectors weren't there, could we perform the acts that they are doing? And, if we couldn't, we have no right to expect them to do it on our behalf. Full stop! That simply compounds the issue. It means that we're not just exploiting animals; we're exploiting human beings."[283]

Environmental veganism

Environmental vegans focus on conservation, rejecting the use of animal products on the premise that fishing, hunting, trapping and farming, particularly factory farming, are environmentally unsustainable. In 2010, Paul Watson of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society called pigs and chicken "major aquatic predators", because livestock eat 40 percent of the fish that are caught.[22] Since 2002[update], all Sea Shepherd ships have been vegan for environmental reasons. This specific form of veganism focuses its way of living on how to have a sustainable way of life without consuming animals.[306]

According to a 2006 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization report, Livestock's Long Shadow, around 26% of the planet's terrestrial surface is devoted to livestock grazing.[307] The UN report also concluded that livestock farming (mostly of cows, chickens and pigs) affects the air, land, soil, water, biodiversity and climate change.[308] Livestock consumed 1,174 million tonnes of food in 2002—including 7.6 million tonnes of fishmeal and 670 million tonnes of cereals, one-third of the global cereal harvest.[309] A 2017 study published in the journal Carbon Balance and Management found animal agriculture's global methane emissions are 11% higher than previous estimates based on data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.[310][311] A 2018 study found that global adoption of plant-based diets would reduce agricultural land use by 76% (3.1 billion hectares, an area the size of Africa) and cut total global greenhouse gas emissions by 28% (half of this emissions reduction came from avoided emissions from animal production including methane and nitrous oxide, and half came from trees re-growing on abandoned farmland which remove carbon dioxide from the air),[312][305] although other research has questioned these results.[313]

A 2010 UN report, Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production, argued that animal products "in general require more resources and cause higher emissions than plant-based alternatives".[315]: 80 It proposed a move away from animal products to reduce environmental damage.[s][316] A 2007 Cornell University study concluded that vegetarian diets use the least land per capita, but require higher quality land than is needed to feed animals.[317] A 2015 study determined that significant biodiversity loss can be attributed to the growing demand for meat, which is a significant driver of deforestation and habitat destruction, with species-rich habitats being converted to agriculture for livestock production.[318][319][320] A 2017 study by the World Wildlife Fund found that 60% of biodiversity loss can be attributed to the vast scale of feed crop cultivation needed to rear tens of billions of farm animals, which puts an enormous strain on natural resources resulting in an extensive loss of lands and species.[321] Livestock make up 60% of the biomass of all mammals on earth, followed by humans (36%) and wild mammals (4%). As for birds, 70% are domesticated, such as poultry, whereas only 30% are wild.[322][323] In November 2017, 15,364 world scientists signed a warning to humanity calling for, among other things, "promoting dietary shifts towards mostly plant-based foods".[324] The 2019 IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services found that industrial agriculture and overfishing are the primary drivers of the extinction crisis, with the meat and dairy industries having a substantial impact.[325][326] On August 8, 2019, the IPCC released a summary of the 2019 special report which asserted that a shift towards plant-based diets would help to mitigate and adapt to climate change.[327]

Feminist veganism

Pioneers

One of the leading activists and scholars of feminist animal rights is Carol J. Adams. Her premier work, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory (1990), sparked what became a feminist movement in animal rights, as she noted the relationship between feminism and meat consumption. Since the release of The Sexual Politics of Meat, Adams has published several other works, including essays, books, and keynote addresses. In one of her speeches, "Why feminist-vegan now?"[328]—adapted from her original address at the "Minding Animals" conference in Newcastle, Australia (2009)—Adams stated that "the idea that there was a connection between feminism and vegetarianism came to [her] in October 1974", illustrating that the concept of feminist veganism has been around for nearly half a century. Other authors have echoed Adams' ideas while also expanding on them. Feminist scholar Angella Duvnjak stated in "Joining the Dots: Some Reflections on Feminist-Vegan Political Practice and Choice" that she was met with opposition when she pointed out the connection between feminist and vegan ideals, even though the connection seemed more than obvious to her and other scholars (2011).[329]

Animal and human abuse parallels

One of the central concepts that animates feminist veganism is the idea that there is a connection between the oppression of women and the oppression of animals. For example, Marjorie Spiegal compared the consumption or servitude of animals for human gain to slavery.[329] This connection is further mirrored by feminist vegan writers like Carrie Hamilton, who pointed out that violent "rapists sometimes exhibit behavior that seems to be patterned on the mutilation of animals" suggesting there is a parallel between the violence of rape and animal cruelty.[330]

Capitalism and feminist veganism

Feminist veganism also relates to feminist thought through the common critique of the capitalist means of production. In an interview with Carol J. Adams, she highlighted "meat eating as the ultimate capitalist product, because it takes so much to make the product, it uses up so many resources".[331] This extensive use of resources for meat production is discouraged in favor of using that productive capacity for other food products that have a less detrimental impact on the environment.

Religious veganism

Streams within a number of religious traditions encourage veganism, sometimes on ethical or environmental grounds. Scholars have especially noted the growth in the twenty-first century of Jewish veganism[332] and Jain veganism.[333] Some interpretations of Christian vegetarianism,[334] Hindu vegetarianism,[335] and Buddhist vegetarianism[336] also recommend or mandate a vegan diet.

Donald Watson argued, "If Jesus were alive today, he'd be an itinerant vegan propagandist instead of an itinerant preacher of those days, spreading the message of compassion, which, as I see it, is the only useful part of what religion has to offer and, sad as it seems, I doubt if we have to enroll our priest as a member of the Vegan Society."[283]

Prejudice against vegans

Vegan rights

In some countries, vegans have some rights to meals and legal protections against discrimination.

- The German police sometimes provides on-duty staff with food. After not being provided a vegan option in this context, a vegan employee has been granted an additional food allowance.[346]

- In Portugal, starting in 2017, public administration canteens and cafeterias such as schools, prisons and social services must offer at least one vegan option at every meal.[347]

- In Ontario, a province of Canada, there were reports[348] that ethical veganism became protected under the Ontario Human Rights Code, following a 2015 update to legal guidance by the Ontario Human Rights Commission. However, said body later issued a statement that this question is for a judge or tribunal to decide on a case-by-case basis.[349]

- In the United Kingdom, a 2020 employment tribunal ruling stated that "ethical veganism" is a belief that qualifies for protection under the Equality Act 2010.[350][351]

Symbols

Multiple symbols have been developed to represent veganism. Several are used on consumer packaging, including the Vegan Society trademark[165] and the Vegan Action logo,[163] to indicate products without animal-derived ingredients.[352][353] Various symbols may also be used by members of the vegan community to represent their identity and in the course of animal rights activism,[citation needed] such as a vegan flag.[354]

Economics of veganism

The documentary film Cowspiracy estimates that a vegan, over the course of one year, will save 1.5 million litres of water, 6,607 kg of grain, 1,022 square metres of forest cover, 3,322 kg of CO2, and 365 animal lives compared to the average U.S. diet.[355][scholarly source needed] According to a 2016 study, if everyone in the U.S. switched to a vegan diet, the country would save $208.2 billion in direct health-care savings, $40.5 billion in indirect health-care savings, $40.5 billion in environmental savings, and $289.1 billion in total savings by 2050. The study also found that if everybody in the world switched to a vegan diet, the global economy would save $684.4 billion in direct health-care savings, $382.6 billion in indirect health-care savings, $569.5 billion in environmental savings, and $1.63 trillion in total savings by 2050.[356]

In his 2015 book Doing Good Better, William MacAskill stated the following (citing numbers from a 2011 book, Compassion by the pound[357]):

Economists have worked out how, on average, a consumer affects the number of animal products supplied by declining to buy that product. They estimate that, on average, if you give up one egg, total production ultimately falls by 0.91 eggs; if you give up one gallon of milk, total production falls by 0.56 gallons. Other products are somewhere in between: economists estimate that if you give up one pound of beef, beef production falls by 0.68 pounds; if you give up one pound of pork, production ultimately falls by 0.74 pounds; if you give up one pound of chicken, production ultimately falls by 0.76 pounds.[358]

See also

Notes

- ^ Other common but less frequent pronunciations recorded by the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary and the Random House Dictionary are /ˈveɪɡən/ VAY-gən and /ˈvɛdʒən/ VEJ-ən.[1][2] The word was coined in Britain by Dorothy Morgan and Donald Watson,[3][4] who preferred the pronunciation /ˈviːɡən/ VEE-gən,[5] and the 1997 edition of the Random House Dictionary reported that this pronunciation was considered "especially British" and that /ˈvɛdʒən/ VEJ-ən was the most frequent and only other common American pronunciation.[6]

- ^ a b "[Al-Maʿarri's] diet was extremely frugal, consisting chiefly of lentils, with figs for sweet; and, very unusually for a Muslim, he was not only a vegetarian, but a vegan who abstained from meat, fish, dairy products, eggs, and honey, because he did not want to kill or hurt animals, or deprive them of their food."[7]

- ^ For veganism and animals as commodities:

Helena Pedersen, Vasile Staescu (The Rise of Critical Animal Studies, 2014): "[W]e are vegan because we are ethically opposed to the notion that life (human or otherwise) can, or should, ever be rendered as a buyable or sellable commodity."[13]

Gary Steiner (Animals and the Limits of Postmodernism, 2013): " ... ethical veganism, the principle that we ought as far as possible to eschew the use of animals as sources of food, labour, entertainment and the like ... [This means that animals] ... are entitled not to be eaten, used as forced field labor, experimented upon, killed for materials to make clothing and other commodities of use to human beings, or held captive as entertainment."[14]

Gary Francione ("Animal Welfare, Happy Meat and Veganism as the Moral Baseline", 2012): "Ethical veganism is the personal rejection of the commodity status of nonhuman animals ..."[15]

- ^ Laura Wright (The Vegan Studies Project, 2015): "[The Vegan Society] definition simplifies the concept of veganism in that it assumes that all vegans choose to be vegan for ethical reasons, which may be the case for the majority, but there are other reasons, including health and religious mandates, people choose to be vegan. Veganism exists as a dietary and lifestyle choice with regard to what one consumes, but making this choice also constitutes participation in the identity category of 'vegan'."[16]

Brenda Davis, Vesanto Melina (Becoming Vegan, 2013): "There are degrees of veganism. A pure vegetarian or dietary vegan is someone who consumes a vegan diet but doesn't lead a vegan lifestyle. Pure vegetarians may use animal products, support the use of animals in research, wear leather clothing, or have no objection to the exploitation of animals for entertainment. They are mostly motivated by personal health concerns rather than by ethical objections. Some may adopt a more vegan lifestyle as they are exposed to vegan philosophy."[17]

Laura H. Kahn, Michael S. Bruner ("Politics on Your Plate", 2012): "A vegetarian is a person who abstains from eating NHA [non-human animal] flesh of any kind. A vegan goes further, abstaining from eating anything made from NHA. Thus, a vegan does not consume eggs and dairy foods. Going beyond dietary veganism, 'lifestyle' vegans also refrain from using leather, wool or any NHA-derived ingredient."[18]

Vegetarian and vegan diets may be referred to as plant-based and vegan diets as entirely plant-based.[19]

- ^ Gary Francione (The Animal Rights Debate, 2010): "Although veganism may represent a matter of diet or lifestyle for some, ethical veganism is a profound moral and political commitment to abolition on the individual level and extends not only to matters of food but also to the wearing or using of animal products."[20]: 62 This terminology is controversial within the vegan community. While some vegan leaders, such as Karen Dawn, endorse efforts to avoid animal consumption for any reason; others, including Francione, believe that veganism must be part of an holistic ethical and political movement in order to support animal liberation. Accordingly, the latter group rejects the label "dietary vegan", referring instead to "strict vegetarians", "pure vegetarians", or followers of a plant-based diet.[21]

- ^ American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2009): "It is the position of the American Dietetic Association that appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets, are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. Well-planned vegetarian diets are appropriate for individuals during all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and for athletes."[23]

- ^ The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung, 2016: "The DGE does not recommend a vegan diet for pregnant women, lactating women, infants, children or adolescents."[28]

- ^ Winston J. Craig (The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2009): "Vegan diets are usually higher in dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamins C and E, iron, and phytochemicals, and they tend to be lower in calories, saturated fat and cholesterol, long-chain n–3 (omega-3) fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B-12. ... A vegan diet appears to be useful for increasing the intake of protective nutrients and phytochemicals and for minimizing the intake of dietary factors implicated in several chronic diseases."[31]