Isan language: Difference between revisions

m →Silent letters: Lao removal and Thai retention: Thai karan was not correct, and removed confusing single quotes. |

|||

| Line 2,430: | Line 2,430: | ||

====Silent letters: Lao removal and Thai retention==== |

====Silent letters: Lao removal and Thai retention==== |

||

Numerous loan words from other languages, particularly Sanskrit and Pali, have numerous silent letters, sometimes even syllables, that are not pronounced in either Thai, Isan or Lao. In most cases, one of the final consonants in a word, or elsewhere in more recent loans from European languages, will have a special mark written over it (Thai |

Numerous loan words from other languages, particularly Sanskrit and Pali, have numerous silent letters, sometimes even syllables, that are not pronounced in either Thai, Isan or Lao. In most cases, one of the final consonants in a word, or elsewhere in more recent loans from European languages, will have a special mark written over it (Thai <big>์ </big> / Lao <big> ໌ </big>' known in Isan as ''karan'' (<big>การันต์</big>) and Lao as ''karan''/''kalan'' (<big>ກາລັນ</big>/archaic <big>ກາຣັນຕ໌</big> {{IPA|/kaː lán/}}). |

||

In reforms of the Lao language, these silent letters were removed from official spelling, moving the spelling of numerous loan words from etymological to phonetical. For instance, the homophones pronounced {{IPA|/tɕan/}} are all written in modern Lao as <big>ຈັນ</big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N, ''chan'', but these were previously distinguished in writing as <big>ຈັນ<u>ທ໌</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]</u> or <big>ຈັນ<u>ທຣ໌</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]-[R]</u>, 'moon'; <big>ຈັນ<u>ທ໌</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]</u> or <big>ຈັນ<u>ທນ໌</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]-[N]</u>, 'sandalwood' and <big>ຈັນ</big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N, 'cruel.' In Isan, using Thai etymological spelling, the respective spellings are <big>จัน<u>ทร์</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]-[R]</u>, <big>จัน<u>ทน์</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]-[N]</u> and <big>จัน</big>, CH-<sup>A</sup>-N, with the latter being a shared Lao-Isan word with no Thai cognate. |

In reforms of the Lao language, these silent letters were removed from official spelling, moving the spelling of numerous loan words from etymological to phonetical. For instance, the homophones pronounced {{IPA|/tɕan/}} are all written in modern Lao as <big>ຈັນ</big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N, ''chan'', but these were previously distinguished in writing as <big>ຈັນ<u>ທ໌</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]</u> or <big>ຈັນ<u>ທຣ໌</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]-[R]</u>, 'moon'; <big>ຈັນ<u>ທ໌</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]</u> or <big>ຈັນ<u>ທນ໌</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]-[N]</u>, 'sandalwood' and <big>ຈັນ</big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N, 'cruel.' In Isan, using Thai etymological spelling, the respective spellings are <big>จัน<u>ทร์</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]-[R]</u>, <big>จัน<u>ทน์</u></big> CH-<sup>A</sup>-N-<u>[TH]-[N]</u> and <big>จัน</big>, CH-<sup>A</sup>-N, with the latter being a shared Lao-Isan word with no Thai cognate. |

||

Revision as of 17:06, 25 June 2021

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Isan | |

|---|---|

| Northeastern Thai, Thai Isan, Lao Isan, Lao (informally) | |

ภาษาลาว, ภาษาอีสาน | |

| Native to | Thailand |

| Region | Isan (Northeastern Thailand). Also in adjacent areas and Bangkok. |

| Ethnicity | Isan (Tai Lao). Second or third language of numerous minorities of the Isan region. |

Native speakers | 13-16 million (2005)[1] 22 million (2013) (L1 and L2)[1][2] |

Kra–Dai

| |

| Tai Noi (former, secular) Tai Tham (former, religious)[3] Thai alphabet (de facto) | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | tts |

| Glottolog | nort2741 |

Isan or Northeastern Thai (Template:Lang-th) refers to the local development of the Lao language in Thailand, after the political split of the Lao-speaking world at the Mekong River, with the left bank eventually becoming modern Laos and the right bank the Isan region of Thailand (formerly known as Siam prior to 1932), after the conclusion of the Franco-Siamese War of 1893. The language is still referred to as Lao by native speakers.[4] As a descendant of the Lao language, Isan is also a Lao-Phuthai language of the Southwestern branch of Tai languages in the Kra-Dai language family, most closely related to its parent language Lao and 'tribal' Tai languages such as Phuthai and Tai Yo. Isan is officially classified as a dialect of the Thai language by the Thai government; although Thai is a closely related Southwestern Tai language, it actually falls within the Chiang Saen languages. Thai and Lao (including Isan) are mutually intelligible with difficulty, as even though they share over 80% cognate vocabulary, Lao and Isan have a very different tonal pattern, vowel quality, manner of speaking and many very commonly used words that differ from Thai thus hampering inter-comprehension without prior exposure.[5]

The Lao language has a long presence in Isan, arriving with migrants fleeing southern China sometime starting the 8th or 10th centuries that followed the river valleys into Southeast Asia. The region of what is now Laos and Isan was nominally united under the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang (1354–1707). After the fall of LanXang, the Lao splinter kingdoms became tributary states of Siam. During the late 18th and much of the 19th century, Siamese soldiers looking to weaken the power of the Lao kings carried out forced migrations of Lao from the left to the right bank, now Isan, impressing people for enslavement, corvée projects, the Siamese armies, or developing the dry Khorat Plateau for farming to feed the growing population. As a result of massive movements, Lao speakers comprise almost one-third of the population of Thailand and represent more than 80% of the population of Lao speakers overall. It is natively spoken by roughly 13-16 million (2005) people of Isan, although the total population of Isan speakers, including Isan people in other regions of Thailand, and those that speak it as a second language, likely exceeds 22 million.[2][1]

The Lao language in Thailand was preserved due to the Isan region's large population, mountains that separated the region from the rest of the country, a conservative culture and ethnic appreciation of their local traditions. The language was officially banned from being referred to as the Lao language in official Thai documents at the turn of the 20th century. Assimilatory laws of the 1930s that promoted Thai nationalism, Central Thai culture and mandatory use of Standard Thai led to the region's inhabitants largely being bilingual and viewing themselves as Thai citizens and began a diglossic situation. Standard Thai is the sole language of education, government, national media, public announcements, official notices and public writing, and even gatherings of all Isan people, if done in an official or public context, are compelled to be in Thai, reserving Isan as the language of the home, agrarian economy and provincial life. The Tai Noi script was also banned, thus making Isan a spoken language, although an ad hoc system of using Thai script and spelling of cognate words is used in informal communication.[5]

Isan is also a more agricultural area and one of the poorest, least developed regions of Thailand, with many Isan people having little education often leaving for Bangkok or other cities and even abroad for work, often employed as laborers, domestics, cooks, taxi drivers, construction and other menial jobs. Combined with historic open prejudice towards Isan people and their language, this has fueled a negative perception of the language. Despite its vigorous usage, since the mid-20th century, the language has been undergoing a slow relexification by Thai or language shift to Thai altogether, threatening the vitality of the language.[6][7] However, with attitudes toward regional cultures becoming more relaxed in the late 20th century onwards, increased research into the language by Thai academics at Isan universities and an ethno-political stance often at odds with Bangkok, some efforts are beginning to take root to help stem the slow disappearance of the language, fostered by a growing awareness and appreciation of local culture, literature and history.[8][5]

Classification

| Kra-Dai |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As a variety of the Lao language, Isan is most closely related to the Lao language as spoken in Laos, but also other Lao-Phuthai languages such as Phuthai and Tai Yo. The relationship is also close to Thai, but Thai and the other regional Tai languages of Thailand are in the Chiang Saen languages. Both the Chiang Saen, Lao-Phuthai and Northwestern Tai languages, which includes the speech of most of Dai and Shan, form the Southwestern branch of the Tai languages, itself the largest and most diverse of the various limbs of the Kra-Dai language family. The Southwestern Tai languages are particularly close, with most languages mutually intelligible to some extent. Thai and Lao have historically influenced each other through contact, as well as the shared corpus of learned Khmer, Sanskrit and Pali loan words in the formal registers which have pushed the spoken languages closer together, but enough phonological and lexical differences remain to make mutual intelligiblity difficult without prior exposure.

Within Thailand, Isan is officially classified as a 'Northeastern' dialect of the Thai language and is referred to as such in most official and academic works concerning the language produced in Thailand. The use of 'Northeastern Thai' to refer to the language is re-enforced internationally with the descriptors in the ISO 639-3 and Glottolog language codes.[9][10] Outside of official and academic Thai contexts, Isan is usually classified as a particular sub-grouping of the Lao language such as by native speakers, Laotian Lao and many linguists, it is also classified as a separate language in light of its unique history and Thai-languge influence, such as its classification in Glottolog and Ethnologue.[4][10][2]

Names

Isan people have traditionally referred to their speech as Phasa Lao (ภาษาลาว, ພາສາລາວ /pʰáː săː láːw/) or 'Lao language'. This is sometimes modified with the word tai (ไท, ໄທ, /tʰáj/), which signifies an 'inhabitant' or 'people', or the related form Thai (ไทย, ໄທ, /tʰáj/), which refers to Thailand or the Thai people, thus yielding Phasa Tai Lao (ภาษาไทลาว, ພາສາໄທລາວ), 'language of the Lao people' and Phasa Thai Lao (ภาษาไทยลาว, ພາສາໄທລາວ), 'Lao language of Thailand'. Lao derives from an ancient Austroasiatic loan into Kra-Dai, *k.ra:w, which signified a '(venerable) person' and is also ultimately the source of the Isan words lao (ลาว, ລາວ, /láːw/), 'he'/'she'/'it', and hao (เฮา, ເຮົາ, /háo/), 'we'. Tai and Thai both derive from another Austroasiatic loan into Kra-Dai, *k.riː, which signifies a '(free) person'. The various Kra-Dai peoples have traditionally used variants of either *k.riː or *k.ra:w as ethnic and linguistic self-appellations, sometimes even interchangeably.[11]

Isan people tend to only refer to themselves and their language as Lao when in Northeastern Thailand where ethnic Lao form the majority of the population, or in private settings of other Isan people, typically away from other Thai-speaking people, where the language can be used freely. Isan speakers typically find the term Lao offensive when used by outsiders due to its usage as a discriminatory slur directed against the Isan people, often insinuating their rural upbringings, superstitious beliefs, links with the Lao people of Laos (i.e., not Thai) and traditional, agrarian lifestyles. In dealings with Lao people from Laos, Isan people may sometimes use Phasa Lao Isan, or 'Isan Lao language', or simply Isan when clarification is needed as to their origins or why the accents differ. The use of Lao or Lao Isan identity, although eschewed by younger generations, is making a comeback, but use of these terms outside of private settings of Isan people or with other Lao people, has strong political associations, especially with the far-left political movements advocating greater autonomy for the region.[12]

As a result, younger people have adopted the neologism Isan to describe themselves and their language as it conveniently avoids ambiguity with the Laotian Lao as well as association with movements, historical and current, that tend to be leftist and at odds with the central government in Bangkok. The language is also called affectionately Phasa Ban Hao (ภาษาบ้านเฮา, ພາສາບ້ານເຮົາ, /pʰáː săː bȃːn háo/), which can be translated as either 'our home language' or 'our village language'.[citation needed]

Isan is known in Thai by the following two names used officially and academically: Phasa Thai Tawan Ok Chiang Neua (ภาษาไทยตะวันออกเฉียงเหนือ /pʰaː săː tʰaj tàʔ wan ʔɔ`ːk tɕʰǐaŋ nɯːa/), 'Northeastern Thai language', or Phasa Thai Thin Isan (ภาษาไทยถิ่นอีสาน /pʰaː săː tʰaj tʰìn ʔiː săːn/), 'Thai language of the Isan region'. These names emphasise the official position of Isan speech as a dialect of the Thai language. In more relaxed contexts, Thai people generally refer to the language as Phasa Thai Isan (ภาษาไทยอีสาน), the 'Isan Thai language' or simply Phasa Isan (ภาษาไทยถิ่นอีสาน, /pʰaː săː tʰaj tʰìn ʔiː săːn/), 'Isan language'.[10][2]

The term Isan derives from an older form อีศาน which in turn is a derivative of Sanskrit Īśāna (ईशान) which signifies the 'northeast' or 'northeastern direction' as well as the name of an aspect of Lord Shiva, as guardian of that direction. It was also the name of the Khmer capital of Chenla whose rule extended over the southern part of the region. After the integration of the Monthon Lao into Siam in 1893, the Siamese also abolished the use of the terms of Lao in place names as well as self-references in the census to encourage assimilation of the Lao people within its new borders. However, due to the distinct culture and language, and the need to disassociate the people and region from Laos, the term Isan came into being for the region of Isan as well as its ethnic Lao people and their Lao speech although it originally only referred to districts which now comprise the southern portion of Northeastern Thailand.[13]

Use of Lao by native Thai speakers was originally used to reference all Tai peoples that were not Siamese, and was once used to refer to Northern Thai people as well, but the term gradually came to be thought of only referring to the ethnic Lao people of Isan and contemporary Laos. When used by Thai people, it is often offensive, given the history of prejudice harboured against Isan people for their distinct culture and language distinct from Thai, as well as perceived links with the communist Lao in Laos. Nevertheless, within Northeastern Thailand, Lao is the general term used by the various ethnic minorities that speak it as a first, second or third language. Thai speakers may also use Phasa Ban Nok (ภาษาบ้านนอก) /pʰaː săː bân nɔ̑ːk/, which can translate as 'rural', 'upcountry' or 'provincial language'. Although it is often used by Thai speakers to refer to the Isan language, since the region is synonymous in Thai minds to rural agriculture, it is also used for any rural, unsophisticated accent, even of Central Thai.[14]

In Laos, the Lao people also refer to the language as Phasa Lao (ພາສາລາວ, /pʰáː săː láːw/), but when necessary to distinguish it from the dialects as spoken in Laos, the terms Phasa Tai Lao (ພາສາໄທລາວ /pʰáː săː tʰáj láːw/), 'Lao language of Thailand' (can also mean 'language of the Lao people') as well as Phasa Lao Isan (ພາສາລາວອີສານ, /pʰá ː săː láːw ʔiː săːn/), 'Isan Lao language', can also be used. In most other languages of the world, 'Isan' or translations of 'Northeastern Thai language' are used.[9][10]

Geographical distribution

The homeland of the Isan language is mainly the twenty provinces of Northeastern Thailand, also known as Phak Isan (ภาคอีสาน), 'Isan region' or just Isan. The region is covered by the flat topography of the Khorat Plateau. The Lao language was able to thrive in the region due to its historical settlement pattern, which included the vast depopulation of the left bank of the Mekong to the right bank and its geographical isolation from the rest of what is now Thailand. The peaks of the Phetsabun and Dong Phanya Nyen mountains to the west and the Sankamphaeng to the southwest separate the region from the rest of Thailand and the Damlek ridges forming the border with Cambodia. The Phu Phan Mountains divide the plateau into a northern third drained by the Loei and Songkhram rivers and a southern third drained by the Mun River and its predominate tributary, the Si. The Mekong River 'separates' Isan speakers from Lao speakers in Laos as it is the geopolitical boundary between Thailand and Laos, with a few exceptions.

Isan speakers spill over into some portions of Uttaradit and Phitsanulok provinces as well as the easternmost fringes of Phetsabun to the northwest of the Isan region, with speakers in these areas generally speaking dialects akin to Louang Phrabang. In the southwest, Isan speakers are also found in portions of Sa Kaeo and Phrasinburi provinces. In addition, large numbers of Isan people have left the region for other major cities of Thailand for employment, with large pockets of speakers found in Bangkok and its surrounding areas as well as major cities across the region. Outside of Thailand, it is likely that Isan speakers can also be found in the United States, South Korea, Australia, Taiwan and Germany which house the largest populations of Overseas Thai.

History

Shared history with the Lao language

Separate development of the Isan language

Integration Period (1893—1932)

After the French established their protectorate over the left bank Lao-speaking territories that became Laos during the conclusion of the Franco-Siamese War of 1893, the right bank was absorbed into Siam which was then ruled by King Wachirawut. To prevent further territorial concessions, the Siamese implemented a series of reforms that introduced Western concepts of statehood, administrative reforms and various measures to integrate the region which was until this point ruled as semi-autonomous out-lying territories nominally under the authority of the Lao kings. With the creation of provinces grouped into districts known as monthon (มณฑล, ມົນທົນ, /món tʰón/), the power of local Lao princes of the mueang in tax collection and administration was moved and replaced by crown-appointed governors from Bangkok which removed the official use of Lao written in Tai Noi in local administration. To achieve this, King Wachirawut had the help of his brother, Prince Damrongrachanuphap who recommended the system. The end of local autonomy and the presence of foreign troops led the Lao people to rebel under the influence of millennialist cult leaders or phu mi bun (ผู้มีบุญ, ຜູ້ມີບຸນ, /pʰȕː míː bun/) during the Holy Man's Rebellion (1901—1902), the last united Lao resistance to Siamese rule, but the rebellion was brutally suppressed by Siamese troops and the reforms were fully implemented in the region shortly afterward.[15][16][17]

Further reforms were implemented to assimilate and integrate the people of the "Lao Monthon" into Siam. References to the 'Lao' and many cities and towns were renamed, such as the former districts Monthon Lao Gao and Monthon Lao Phuan which were renamed as 'Monthon Ubon' and 'Monthon Udon', respectively, shortly after their creation in 1912. Self-designation as Lao in the census was banned after 1907, with the Lao forced to declare themselves as Thai and speakers of a Thai dialect. The unofficial use of Lao to refer to them was discouraged, and the term 'Isan', originally just a name of the southern part of the 'Lao Monthon', was extended to the entire region, its primary ethnic group and language. The name change and replacement of the Lao language by Thai at the administrative level and reforms to implement Thai had very little effect as the region's large Lao population and isolation prevented quick implementation. Monks still taught young boys to read the Tai Noi script written on palm-leaf manuscripts since there were no schools, passages from old literature were often read during festivals and traveling troupes of mo lam and shadow puppet performers relied on written manuscripts for the lyrics to poetry and old stories set to song and accompanied by the khaen alone or alongside other local instruments. Mountains, lack of roads, large areas without access to water during the dry season and flooding in the wet season continued to shield the Isan people and their language from direct Thai-language influence.[15][17]

Thaification (1930s–1960s)

Suppression of the Isan language came with the 'Thai cultural mandates' and other reforms that aimed to elevate Central Thai culture and language, reverence to the monarchy and the symbols of state and complete integration into Thailand, known as 'Thaification'. Most of these reforms were implemented by Plaek Phibunsongkhram, who changed the English name of Siam to 'Thailand' and whose ultra-nationalistic policies would mark Thailand during his rule from 1938 to 1944 and 1948–1957. These policies implemented an official diglossia. Isan was removed from public and official discourse to make way for Thai and the written language was banned, relegating Isan to an unwritten language of the home. Public schools, which finally were built in the region, focussed heavily on indoctrinating Isan people to revere the Thai monarchy, loyalty to the state and its symbols and mastery of the Thai language, with Isan treated as an inferior dialect. Pride in the language was erased as students were punished or humiliated for using the language in the classroom or writing in Tai Noi, planting the seed for future language shift as the region became bilingual.[17][15][18]

The old written language and the rich literature written in it were banned and was not discussed in schools. Numerous temples had their libraries seized and destroyed, replacing the old Lao religious texts, local histories, literature and poetry collections with Thai-script, Thai-centric manuscripts. The public schools also dismissed the old monks from their role as educators unless they complied with the new curriculum. This severed the Isan people from knowledge of their written language, shared literary history and ability to communicate via writing with the left bank Lao. In tandem with its removal from education and official contexts, the Thai language made a greater appearance in people's lives with the extension of the railroad to Ubon and Khon Kaen and with it the telegraph, radio and a larger number of Thai civil servants, teachers and government officials in the region that did not learn the local language.[19]

Words for new technologies and the political realities of belonging to the Thai state arrived from Thai, including words of English and Chinese (primarily Teochew) origin, as well as neologisms created from Sanskrit roots. Laos, still under French rule, turned to French, Vietnamese, repurposing of old Lao vocabulary as well as Sanskrit-derived coinages that were generally the same, although not always, as those that developed in Thai. For example, the word or aeroplane (UK)/airplane (US) in Isan was huea bin (Template:Lang-tts /hɨ́a bìn/) 'flying boat', but was generally replaced by Thai-influenced khrueang bin (Template:Lang-tts /kʰɨ̄aŋ bìn/) 'flying machine', whereas Lao retained hua bin (Template:Lang-lo /hɨ́a bìn/) RTSG huea bin. Similarly, a game of billiards /bɪl jədz/ in Isan is (Template:Lang-tts /bin lȋaːt/ from English via Thai; whereas on the left bank, people play biya (Template:Lang-lo /bìː jàː/) from French billard /bi jaʀ/. Despite this slow shift, the spoken language maintained its Lao features since most of the population was still engaged in agriculture, where Thai was not needed, thus many Isan people never mastered Thai fully even if they used it as a written language and understood it fine.[17][18]

1960s to Present

The language shift to Thai and the increased influence of the Thai language really came to the fore in the 1960s due to several factors. Roads were finally built into the region, making Isan no longer unreachable for much of the year, and the arrival of television with its popular news broadcasts and soap operas penetrated into people's homes at this time. As lands new lands to clear for cultivation were no longer available, urbanization began to occur, as well as the massive seasonal migration of Isan people to Bangkok during the dry season, taking advantage of the economic boom occurring in Thailand with increased western investment due to its more stable, non-communist government and openness. Having improved their Thai during employment in Bangkok, the Isan people returned to their villages, introducing the Bangkok slang words back home and peppering their speech with more and more Thai words.[citation needed]

Around the 1990s, although the perceived political oppression continues and Thaification policies remain, attitudes towards regional languages relaxed. Academics at Isan universities began exploring the local language, history, culture and other folklore, publishing works that helped bring serious attention to preserving the Lao features of the language and landscape, albeit under an Isan banner. Students can participate in clubs that promote local music, sung in the local Lao language, or local dances native to the area. Knowledge about the history of the region and its long neglect and abuse by Siamese authorities and resurrection of pride in local culture are coming to the fore, increasing expressions of 'Isan-ness' in the region. However, Thaification policies and the language shift to Thai continue unabated. Recognition of the Isan language as an important regional language of Thailand did not provide any funding for its preservation or maintenance other than a token of acknowledgment of its existence.[5][20]

Language status

Legal status

Ethnologue describes the Isan language as 'de facto language of provincial identity' which 'is the language of identity for citizens of the province, but this is not mandated by law. Neither is it developed enough or known enough to function as the language of government business.' Although Thailand does recognise the regional Tai languages, including Isan, as important aspects of regional culture and communication, the Isan language and other minority languages are still inferior to the social and cultural prestige of Standard Thai and its government sanctioned promotion in official, educational and national usage. However, the Thaification laws that banned the old Lao alphabet and forced the Lao to refer to themselves and their language as 'Thai Isan' never banned the language in the home nor the fields and the Isan people steadfastly clung to their spoken language.[21]

The situation is in stark contrast to Laos where the Lao language is actively promoted as a language of national unity. Laotian Lao people are very conscious of their distinct, non-Thai language and although influenced by Thai-language media and culture, strive to maintain 'good Lao'. Although spelling has changed, the Lao speakers in Laos continue to use a modified form of the Tai Noi script, the modern Lao alphabet.[22]

Spoken status

According to the EGIDS scale, Isan is at Stage VIA, or 'vigorous', meaning the language is used for 'face-to-face communication by all generations and the situation is sustainable'.[23] Although various studies indicate that Isan is spoken by almost everyone in Northeastern Thailand, the language is under threat from Thai, as Thai replaces the unique vocabulary specific to Lao speakers, and language shift, as more and more children are being raised to speak only Standard Thai. The lack of prestige of the language and the need for Thai to advance in government, education and professional realms or seek employment outside of Northeastern Thailand, such as Bangkok, necessitate the use and mastery of proper Thai over proper Lao.[5]

The language suffers from a negative perception and diglossia, so speakers have to limit their use of the language to comfortable, informal settings. Parents often view the language as a detriment to the betterment of their children, who must master Standard Thai to advance in school or career paths outside of agriculture. The use of the Thai script, spelling cognate words in Isan as they are in Thai, also gives a false perception of the dialectal subordination of Isan and the errors of Isan pronunciation which deviate from Thai. As a result, a generational gap has arisen with old speakers using normative Lao and younger speakers using a very 'Thaified' version of Isan, increased code-switching or outright exclusive use of Thai. Many linguists and scholars of the Isan language believe that Thai relexification cannot be halted unless the script is returned, but this has little public or government support.[24][5]

Written language usage and vitality

The written language is currently at Stage IX, which on the EGIDS scale is a 'language [that] serves as a reminder of heritage identity for an ethnic community, but no one has more than symbolic proficiency'.[23] This applies to both the Tai Noi script used for secular literature and the Tua Tham script previously used for Buddhist texts. Only a handful of people of very advanced age and caretakers of monasteries whose libraries were not destroyed during the Thaification implementation in the 1930s are able to read either script. Evidence for the use of the written language is hard to find, but well-worn murals of very old temples often have small bits of writing in the old script.[25]

In Laos, the orthography is a direct descendant of Tai Noi and continues its role as the official written language of the Lao language of the left bank as well as the script used to transcribe minority languages. The Lao written language has unified the dialects to some extent as well, as though the differences between dialects are sharper in Laos than Isan, one common writing system unites them.[22][25]

Language threats

Negative perceptions

Acknowledgment of the unique history of the Isan language and the fact it is derived from a closely related albeit separate language is lacking, with the official and public position being that the language is a dialect of Thai. As a result of the great difference from Thai, based on tone, nasal vowels of a different quality and a special set of Lao vocabulary unfamiliar to Thai speakers, it is considered an 'inferior form of Thai' as opposed to its own separate language. The traditional avoidance of the language in the formal sphere re-enforces the superiority of Thai, which the Isan people have internalized to the point many do not have high opinions of their first language. Combined with vocabulary retentions, many of which sound oddly archaic or have become pejorative in Standard Thai, perpetuate the myth and negative perception of Isan as an uncouth language of rural poverty and hard agricultural life. Due to associations with Laos, the language was also viewed as a potential fifth column for Lao irredentism and the spread of communism into Thailand.[26] It was in the recent past quite common for Isan people to be corrected or ridiculed when they spoke because of their incomplete mastery of Standard Thai.[27]

In polling of language favorability amongst the general population of Thailand, the Isan language ranks last after Standard Thai and the primary Thai dialect of the other regions.[28] As a result of the need for Standard Thai proficiency in order to have better educational and employment prospects and avoid discrimination, anecdotal evidence suggests that more and more Isan children are being raised in the Thai language and are discouraged from using the local language at home.[27] The Thai language has already begun to displace the predominance of Isan in the major market towns, in part because they are often also administrative centers, and in some major cities, universities have attracted students from other regions.[26]

Code-switching

Since the late 1930s, Isan has been a bilingual area, with most people using Isan at home and in the village, but due to diglossia, switching to Thai for school, work and formal situations. Like all bilingual societies, Isan speakers often code-switch in and out of the Thai language. For example, in an analysis of the eighty-eight volumes of the comic 'Hin the Mouse' in the city, the Thai language was used 62.91 percent of the time to properly quote someone—such as someone that speaks Thai, 21.19 percent of the time to provide further explanation and 8.61 percent of the time to re-iterate a previous statement for clarification.[29] There are seven areas where the Thai language is employed, aside from direct quotation, such as the following: explanations, interjections, Thai culture, emphasis, re-iterations and jokes.[30]

Although some Isan people may not speak the language well, Thai is a convenient language of clarification, especially between Isan speakers of different dialects that may be unfamiliar with local terms of the other speaker. As Isan does not exist in formal, technical, political or academic domains, it is generally more comfortable for Isan speakers to use Thai in these areas as a result of the diglossia, with many Isan speakers unaware or unfamiliar with native terms and belles-lettres that are still used in contemporary Lao. Thai is also sometimes used to avoid Isan features that are stigmatized in Thai, such as retention of vocabulary that is pejorative or archaic as well as Lao pronunciations of cognate words that sound 'folksy'. Despite the fact that code-switching is a natural phenomenon, younger generations are blurring the distinction between languages, using more Thai-like features and as they forget to switch back to Isan, language shift takes hold.[27][24]

Thai-influenced language shift

The Thai language may not be the primary language of Isan, but Isan people are in constant exposure to it. It is required to watch the ever-popular soap operas, news, and sports broadcasts or sing popular songs, most of it produced in Bangkok or at least in its accent. Thai is also needed as a written language for instructions, to read labels on packages, road signs, newspapers and books. Isan children who may struggle to acquire the language, are forced to learn the language as part of compulsory education and often when they are older, for employment. Although attitudes towards regional cultures and languages began to relax in the late 1980s, the legal and social pressures of Thaification and the need for Thai to participate in daily life and wider society continue. The influence of Thai aside, anecdotal evidence suggests that many older Isan lament the corruption of the spoken language spoken by younger generations and that the younger generations are no longer familiar with the traditional Lao forms used by previous generations.[24][31]

In a 2016 study of language shift, villagers in an Isan-speaking village were divided by age and asked to respond to various questionnaires to determine lexical usage of Lao terms, with those born prior to 1955, those born between 1965 and 1990 and those born after 1990. The results show what would be expected of a language undergoing language shift. As Isan and Thai already have a similar grammatical structure and syntax, the main variance is in lexical shift, essentially the replacement of Isan vocabulary. The oldest generation, at the time in their 60s or older, uses very normative Lao features little different than those found in Laos. The middle generations, ranging from 35 to 50 years of age, had a greater prevalence of Thai vocabulary, but overall maintained a traditional Isan lexicon, with the Thai terms usually not the primary spoken forms. The youngest generation, although still arguably using very many Lao phrases and vocabulary, had a remarkable replacement of Isan vocabulary, with Thai forms becoming either the primary variant or replacing the Isan word altogether. Similarly, when Isan usage has two variants, generally a common one not understood in Thai and another that is usually a cognate, younger speakers tend to use the cognates with greater frequency, pushing their speech to Thai as older speakers will use them in variance.[32]

Thai loan words were generally localized in pronunciation, easing them into the flow of Isan conversation and unnoticeable to most but the oldest members of the community that preserve 'proper Isan' usage. Although the youngest generation was still speaking a distinct language, each generation brings the increased risk of the Isan language's extinction as it becomes relexified to the point of no longer being a separate language but a dialect of Thai with some Lao influence. The lack of official usage, official support for its maintenance and lack of language prestige hinder attempts to revitalize or strengthen the language against the advance of Thai.[31]

| Thai | Isan | Lao | Isan youth | Gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| โหระพา horapha |

/hǒː raʔ pʰaː/ | อี่ตู่ i tu |

/ʔīː tūː/ | ອີ່ຕູ່ i tou |

/ʔīː tūː/ | โหระพา horapha |

/hŏː lāʔ pʰáː/ | 'holy basil' |

| พี่สาว phi sao |

/pʰîː ˈsǎːw/ | เอื้อย | /ʔɨ:əj/ | ເອື້ອຍ | /ʔɨ:əj/ | พี่สาว phi sao |

/pʰīː săːo/ | 'older sister' |

| คนใบ้ khon bai |

/kʰon bâj/ | คนปากกืก khon pak kuek |

/kʰón pȁːk kɨ̏ːk/ | ຄົນປາກກືກ khôn pak kuk |

/kʰón pȁːk kɨ̏ːk/ | คนใบ้ khon bai |

/kʰón bȃj/ | 'mute' (person) |

| กระรอก krarok |

/kraʔ rɔ̂ːk/ | กระฮอก krahok |

/káʔ hɔ̂ːk/ | ກະຮອກ kahok |

/káʔ hɔ̂ːk/ | กระรอก krarok |

/káʔ lɔ̑ːk/ | 'squirrel' |

| กระซิบ krasip |

/kraʔ síp/ | ซับซึ่ม sap suem |

/sāp sɨ̄m/ | ຊັບຊິຶ່ມ xap xum |

/sāp sɨ̄m/ | กระซิบ krasip |

/káʔ sīp/ | 'to whisper' |

| งีบ ngip |

/ŋîːp/ | เซือบ suep |

/sɨ̑ːəp/ | ເຊືອບ xup |

/sɨ̑ːəp/ | งีบ ngip |

/ŋȋːp/ | 'to nap' |

| รวม ruam |

/ruam/ | โฮม hom |

/hóːm/ | ໂຮມ hôm |

/hóːm/ | รวม ruam |

/lúːəm/ | 'to gather together' 'to assemble' |

| ลูก luk |

/lûːk/ | หน่วย nuai |

/nūːəj/ | ຫນ່ວຽ nouay |

/nūːəj/ | ลูก luk |

/lȗːk/ | 'fruit' (classifier) |

| ไหล lai |

/làj/ | บ่า ba |

/bāː/ | ບ່າ ba |

/bāː/ | ไหล lai |

/lāj/ | 'shoulder' |

Continued survival

The development of 'Isan' identity and a resurgence in attention to the language has brought increased attention and study of the language. Academics at universities are now offering courses in the language and its grammar, conducting research into the old literature archives that were preserved. Digitizing palm-leaf manuscripts and providing Thai-script transcription is being conducted as a way to both preserve the rapidly decaying documents and re-introduce them to the public. The language can be heard on national television during off-peak hours, when music videos featuring many Isan artists of molam and Isan adaptations of Central Thai luk thung music. In 2003, HRH Princess Royal Sirinthon was the patron of the Thai Youth Mo Lam Competition.[5]

Phonology

Consonants

Initials

Isan shares its consonant inventory with the Lao language whence it derives. The plosive and affricate consonants can be further divided into three voice-onset times of voiced, tenuis and aspirated consonants. For example, Isan has the plosive set of voiced /b/, tenuis /p/ which is like the 'p' in 'spin' and aspirated /pʰ/ like the 'p' in 'puff'. Isan and Lao lack the sound /tɕʰ/ and its allophone /ʃ/ of Thai, replacing these sounds with /s/ in analogous environments. Similarly, /r/ is rare. Words in Isan and Lao cognate to Thai word with /r/ have either /h/ or /l/ in their place, although educated speakers in Isan or Laos may pronounce some words with /r/. In Thai, words with /r/ may be pronounced as /l/ in casual environments although this is frowned upon in formal or cultivated speech.

Unlike Thai, Isan and Lao have a /j/-/ɲ/ distinction, whereas cognate words from Isan and Lao with /ɲ/ are all /j/ in Thai. Substitution of /enwiki/w/ with /ʋ/, which is not used in Thai, is common in large areas of both Laos and Isan but is not universal in either region, but is particularly associated with areas influenced by Vientiane and Central Lao dialects. The glottal stop occurs any time a word begins with a vowel, which is always built around a null consonant.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | /m/ | /n/ | /ɲ/2,5 | /ŋ/ | ||

| ม, หม4 | ณ1, น, หน4 | ญ3, ย3, หญ3,4, หย3, | ง, หง4 | |||

| ມ, ໝ4/ຫມ4 | ນ, ໜ4/ຫນ4 | ຍ5, ຫຽ4,11/ຫຍ4 | ງ, ຫງ4 | |||

| Stop | Tenuis | /p/ | /t/ | /tɕ/ | /k/ | /ʔ/10 |

| ป | ฏ1,ต | จ | ก | อ10 | ||

| ປ | ຕ | ຈ | ກ | ອ10 | ||

| Aspirate | /pʰ/ | /tʰ/ | /tɕʰ/6 | /kʰ/ | ||

| ผ,พ,ภ | ฐ1, ฑ1, ฒ1, ถ, ท, ธ | ฉ6, ช6, ฌ1,6 | ข, ฃ7, ค, ฅ7, ฆ1 | |||

| ຜ, ພ | ຖ, ທ | ຊ6 | ຂ, ຄ | |||

| Voiced | /b/ | /d/ | ||||

| บ | ฎ1, ด | |||||

| ບ | ດ | |||||

| Fricative | /f/ | /s/ | /h/ | |||

| ฝ,ฟ | ซ, ศ1, ษ1, ส | ห, ฮ9 | ||||

| ຝ, ຟ | ສ, ຊ | ຫ, ຮ9 | ||||

| Approximate | /ʋ/2,5 | /l/ | /j/ | /enwiki/w/ | ||

| ว5, หว4 | ล, ฬ1, ร12, หล4, หร4,12 | ย, หย4 | ว, หว4 | |||

| ວ5, ຫວ4 | ຣ11, ລ, ຫຼ4/ຫລ4, ຫຼ4,11/ຫຣ4,11 | ຢ, ຫຽ4,11/ຫຢ4 | ວ, ຫວ4 | |||

| Trill | /r/8 | |||||

| ร8, หร4,8 | ||||||

| ຣ8,11, ຫຼ4,8/ຫຣ4,8,11 | ||||||

- ^1 Only used in Sanskrit or Pali loan words.

- ^2 Unique to Isan and Lao, does not occur in Thai but /ʋ/ is only an allophone of /enwiki/w/ whereas /ɲ/ is phonemic.

- ^3 Thai spelling does not distinguish /j/ from /ɲ/.

- ^4 Lao ligature of silent /h/ (ຫ) or digraph; Thai digraph with silent /h/ (ห).

- ^5 Only as syllable-initial consonants.

- ^6 Use of /tɕʰ/ is Thai interference in Isan and rare in Laos, usually interference from a northern tribal Tai language, almost always /s/.

- ^7 Still taught as part of the alphabet, 'ฃ' and 'ฅ' are obsolete and have been replaced by 'ข' and 'ค', respectively.

- ^8 Mark of interference from Isan or erudition in Laos. Usually replaced by /l/ and even by 'ລ' /l/ in modern Lao writing.

- ^9 Used to mark /h/ in words that are etymologically /r/.

- ^10 All words that begin with vowels must be written with the anchor consonant and are pronounced with a glottal stop.

- ^11 Generally used in pre-1970s Lao.

- ^12 Only in very casual, informal Thai.

Clusters

Consonant clusters are rare in spoken Lao as they disappear shortly after the adoption of writing. In native words, only /kw/ and /kʰw/ are permissible, but these can only occur before certain vowels due to the diphthongisation that occurs before the vowels /aC/, /am/, /aː/ and /aːj/. Isan speakers, who are educated in Thai and often use Thai spelling of etymological vocabulary to transcribe Isan, will generally not pronounce consonant clusters but may do so when code-switching to Thai or when pronouncing high-brow words of Sanskrit, Pali or Khmer derivation. Lao speakers from Laos will sometimes pronounce clusters in these borrowed loan words, but this is restricted to ageing speakers of the Laotian diaspora.

| Isan | Thai | Lao | Isan | Thai | Lao | Isan | Thai | Lao | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ก | /k/ | ก | /k/ | ກ | /k/ | ค | /kʰ/ | ค | /kʰ/ | ຄ | /kʰ/ | ป | /p/ | ป | /p/ | ປ | /p/ |

| กร | กร | /kr/ | คร | คร | /kʰr/ | ปร | ปร | /pr/ | |||||||||

| กล | กล | /kl/ | คล | คล | /kʰl/ | ปล | ปล | /pl/ | |||||||||

| กว1 | /kw/1 | กว | /kw/ | ກວ1 | /kw/1 | คว1 | /kʰw/1 | คว | /kʰw/ | ຄວ1 | /kʰw/1 | ผ | /pʰ/ | ผ | /pʰ/ | ຜ | /pʰ/ |

| ข | /kʰ/ | ข | /kʰ/ | ຂ | /kʰ/ | ต | /t/ | ต | /t/ | ຕ | /t/ | ผล | ผล | /pʰl/ | |||

| ขร | ขร | /kʰr/ | ตร | ตร | /tr/ | พ | /pʰ/ | พ | /pʰ/ | ພ | /pʰ/ | ||||||

| ขล | ขล | /kʰl/ | พร | พร | /pʰr/ | ||||||||||||

| ขว1 | /kʰw/1 | ขว | /kʰw/ | ຂວ1 | /kʰw/1 | พล | พล | /pʰl/ | |||||||||

- ^1 Before /aC/, /aː/, /aːj/ and /am/ diphthongization occurs which assimilates the /enwiki/w/ so it is only a true cluster in other vowel environments, only occurs in Isan and Lao.

Finals

Isan shares with both Lao and Thai a restrictive set of permissible consonant sounds at the end of a syllable or word. Isan, using its current method of writing according to Thai etymological spelling, preserves the spelling to imply the former sound of borrowed loan words even if the pronunciation has been assimilated. Due to spelling reforms in Laos, the letters that can end a word were restricted to a special set of letters, but older writers and those in the Lao diaspora occasionally use some of the more etymological spellings.

In pronunciation, all plosive sounds are unreleased, as a result, there is no voicing of final consonants or any release of air. The finals /p/, /t/ and /k/ are thus actually pronounced /p̚/, /t̚/, and /k̚/, respectively.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | /m/ |

/n/ |

/ŋ/ | |||||

| ม | ญ,ณ,น,ร,ล,ฬ | ง | ||||||

| ມ | ນ1 | ຣ2, ລ2 | ງ | |||||

| Stop | /p/ | /t/ | /k/ | /ʔ/ | ||||

| บ,ป,พ,ฟ,ภ | จ,ช,ซ,ฌ,ฎ,ฏ,ฐ,ฑ ฒ,ด,ต,ถ,ท,ธ,ศ,ษ,ส |

ก,ข,ค,ฆ | *3 | |||||

| ບ1 | ປ2, ພ2, ຟ2 | ດ1 | ຈ2, ສ2, ຊ2, ຕ2, ຖ2, ທ2 | ກ1 | ຂ2, ຄ2 | |||

| Approximate | /enwiki/w/4 | /j/4 | ||||||

| ว | ย | |||||||

| ວ | ຍ | |||||||

- ^1 Where alternative spellings once existed, only these consonants can end words in modern Lao.

- ^2 Used in pre-1970s Lao spelling as word-final letters.

- ^3 Glottal stop is unwritten but is pronounced at the end of short vowels that occur at the end of a consonant.

- ^4 These occur only as parts of diph- or triphthongs and are usually included as parts of vowels.

Vowels

The vowel structure of Isan is the same as the central and southern Lao dialects of Laos. The vowel quality is also similar to Thai, but differs in that the two back vowels, close back unrounded vowel /ɯ/ and the close-mid back unrounded vowel /ɤ/, centralized as the close central unrounded vowel /ɨ/ and the mid central vowel /ə/, respectively, as well as in diphthongs that may include these sounds. To Thai speakers, Isan and Lao vowels tend to have a nasal quality.

In many cases, especially diphthongs with /u/ as first element is lengthened in Isan as it is in Standard Lao, so that the word tua which means 'body' (Template:Lang-th, written the same in Isan) is pronounced /tua/ in Thai but in Isan as /tuːə/, similar to Template:Lang-lo. The symbol '◌' indicates the required presence of a consonant, or for words that begin with a vowel sound, the 'null consonant' 'อ' or its Lao equivalent, 'ອ', which in words that begin with a vowel, represents the glottal stop /ʔ/. Short vowels that end with '◌ะ' or Lao '◌ະ' also end with a glottal stop.

Thai and Lao are both abugida scripts, so certain vowels are pronounced without being written, taking the form of /a/ in open syllables and /o/ in closed syllables, i.e., ending in a consonant. For example, the Khmer loan word phanom or 'hill' found in many place names in Isan is Template:Lang-tts or 'PH-N-M' but pronounced /pʰāʔ nóm/, with 'PH' as the open syllable and 'N-M' as the closed syllable. In Lao orthography, inherited from Tai Noi, closed syllables are marked with a 'ົ' over the consonants and the /a/ of open syllables was unwritten, thus Template:Lang-lo or 'Ph-N-o-M'. In current practice as a result of spelling reforms, all vowels are written out and in modern Template:Lang-lo or 'Ph-a-N-o-M' is more common thus modern Lao is no longer a true abugida.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | /i/ | /ɨ/ ~ /ɯ/ | |

| Close-Mid | /e/ | /o/ | |

| Mid | /ə/ ~ /ɤ/ | ||

| Open-Mid | /ɛ/ | /ɔ/ | |

| Open | /a/ | ||

Vowel length

Vowels usually exist in long-short pairs determined by vowel length which is phonemic, but vowel length is not indicated in the RTSG romanization used in Thai or the BGN/PCGN French-based scheme commonly used in Laos. The Isan word romanized as khao can represent both Template:Lang-tts /kʰăo/, 'he' or 'she', and Template:Lang-tts /kʰăːo/, 'white' which corresponds to Template:Lang-lo and Template:Lang-lo, respectively, which are also romanized as khao. In these cases, the pairs of words have the same tone and pronunciation and are differentiated solely by vowel length.

| Long vowels | Short vowels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thai | IPA | Lao | IPA | Thai | IPA | Lao | IPA |

| ◌ำ | /am/ | ◌ຳ | /am/ | ||||

| ◌า | /aː/ | ◌າ | /aː/ | ◌ะ, ◌ั, *1 | /aʔ/, /a/ | ◌ະ, ◌ັ | /aʔ/, /a/ |

| ◌ี | /iː/ | ◌ີ | /iː/ | ◌ิ | /i/ | ◌ິ | /i/ |

| ◌ู | /uː/ | ◌ູ | /uː/ | ◌ุ | /u/ | ◌ຸ | /u/ |

| เ◌ | /eː/ | ເ◌ | /eː/ | เ◌ะ, เ◌็ | /eʔ/, /e/ | ເ◌ະ, ເ◌ົ | /eʔ/, /e/ |

| แ◌ | /ɛː/ | ແ◌ | /ɛː/ | แ◌ะ, แ◌็ | /ɛʔ/, /ɛ/ | ແ◌ະ, ແ◌ົ | /ɛʔ/, /ɛ/ |

| ◌ื, ◌ือ | /ɯː/ | ◌ື | /ɨː/ | ◌ื | /ɯ/ | ◌ຶ | /ɨ/ |

| เ◌อ, เ◌ิ | /ɤː/ | ເີ◌ | /əː/ | เ◌อะ | /ɤʔ/ | ເິ◌ | /əʔ/ |

| โ◌ | /oː/ | ໂ◌ | /oː/ | โ◌ะ, *2 | /oʔ/, /o/ | ໂ◌ະ, ◌ົ | /oʔ/, /o/ |

| ◌อ | /ɔː/ | ◌ອ◌, ◌ໍ | /ɔː/ | เ◌าะ | /ɔʔ/ | ເ◌າະ | /ɔʔ/ |

Diphthongs

| Long vowels | Short vowels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thai | IPA | Lao | IPA | Thai | IPA | Lao | IPA |

| ◌วำ3 | /wam/ | ◌ວຳ | /uːəm/ | ||||

| ◌าย | /aːj/ | ◌າຍ/◌າຽ2 | /aːj/ | ไ◌1, ใ◌1, ไ◌1,◌ัย | /aj/ | ໄ◌1, ໃ◌1, ໄ◌ຍ1,2/ໄ◌ຽ2, ◌ັຍ2/◌ັຽ2 | /aj/ |

| ◌าว | /aːw/ | ◌າວ | /aːw/ | เ◌า1 | /aw/ | ເ◌ົາ1 | /aw/ |

| ◌ัว, ◌ว◌ | /ua/ | ◌ົວ, ◌ວ◌, ◌ວາ, | /uːə/ | ◌ัวะ | /uəʔ/ | ◌ົວະ, ◌ົວ | /uəʔ/, /uə/ |

| ◌ิิว | /iw/ | ◌ິວ | /iw/ | ||||

| เ◌ีย | /iːə/ | ເ◌ັຍ/ເ◌ັຽ2, ◌ຽ◌ | /iːə/ | เ◌ียะ | /iːəʔ/ | ເ◌ົຍ/ເ◌ົຽ2, ◌ົຽ◌ | /iə/ |

| ◌อย | /ɔːj/ | ◌ອຍ/◌ອຽ2 /◌ຽ2 | /ɔːj/ | ||||

| โ◌ย | /oːj/ | ໂ◌ຍ/ໂ◌ຽ2 | /oːj/ | ||||

| เ◌ือ, เ◌ือ◌ | /ɯːa/ | ເ◌ືອ, ເ◌ືອ◌ | /ɨːə/ | เ◌ือะ | /ɯaʔ/ | ເ◌ຶອ | /ɨəʔ/ |

| ◌ัว, ◌ว◌ | /ua/ | ◌ັວ, ◌ວ◌, ◌ວາ, | /uːə/ | ◌ัวะ | /uaʔ/ | ◌ົວະ, ◌ົວ | /uəʔ/, /uə/ |

| ◌ูย | /uːj/ | ◌ູຍ/◌ູຽ2 | /uːj/ | ◌ຸย | /uj/ | ◌ຸຍ/◌ຸຽ2 | /uj/ |

| เ◌ว | /eːw/ | ເ◌ວ | /eːw/ | เ◌็ว | /ew/ | ເ◌ົວ | /ew/ |

| แ◌ว | ɛːw | ແ◌ວ | /ɛːw/ | ||||

| เ◌ย | /ɤːj/ | ເ◌ີຍ/ເ◌ີຽ2 | /əːj/ | ||||

- ^1 Considered long vowels for the purpose of determining tone.

- ^2 Archaic usage common in pre-1970s Lao.

- ^3 The Thai vowel 'ำ' is a short vowel. In Isan, it is diphthongized after /enwiki/w/ into /uːəm/.

Triphthongs

| Thai | IPA | Lao | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| เ◌ียว1 | /iaw/ | ◌ຽວ1 | /iːəw/ |

| ◌วย1 | /uəj/ | ◌ວຍ/◌ວຽ1,2 | /uːəj/ |

| เ◌ือย1 | /ɯəj/ | ເ◌ືວຍ1/ເ◌ືວຽ1,2 | /ɨ:əj/ |

- ^1 Considered long vowels for the purpose of determining tone.

- ^2 Archaic usage common in pre-1970s Lao.

Special vowels

As Isan is written in Thai, it also has the following symbols not found in the Lao script or its predecessor, Tai Noi. The letters are based on vocalic consonants used in Sanskrit, given the one-to-one letter correspondence of Thai to Sanskrit, although the last two letters are quite rare, as their equivalent Sanskrit sounds only occur in a few, ancient words and thus are functionally obsolete in Thai. The first symbol 'ฤ' is common in many Sanskrit and Pali words and 'ฤๅ' less so, but does occur as the primary spelling for the Thai adaptation of Sanskrit 'rishi' and treu (Template:Lang-th /trɯː/ or /triː/), a very rare Khmer loan word for 'fish' only found in ancient poetry.

In the past, prior to the turn of the twentieth century, it was common for writers to substitute these letters in native vocabulary that contained similar sounds as a shorthand that was acceptable in writing at the time. For example, the conjunction 'or' (Template:Lang-th /rɯ́/ reu, cf. Template:Lang-lo /lɨ̑ː/ lu) was often written Template:Lang-th such as in 'เขาไปบ้านแล้วหรือยัง' (Did he go home yet or not?) formerly written 'เขาไปบ้านแล้วฤยัง'. The practice had become obsolete by the time that Isan speakers began adopting Thai writing, but Isan speakers are likely exposed to it in school when studying Thai literature. These letters did not occur in Tai Noi or the modern Lao alphabet, and equivalent words of Sanskrit origin are spelled out with other letters. Isan speakers historically, and many still do, use the Lao pronunciation of these words.

| Vowel | Sound | Phonetic equivalent | Thai example/Lao cognate | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ฤ | /ri/, /rɯ/, /rɤː/ | ริ, รึ เรอ/เริ◌ | rit ฤทธิ์ /rít/ lit/rit ລິດ/ຣິດ1/ຣິດຖ໌1 /līt/ |

'supernatural power' |

| ฤๅ | /rɯː/ | รือ/รื◌ | ruesi ฤๅษี /rɯː sǐː/ lusi/rusi ລຶສີ/ຣືສີ1 /lɨ̄ sǐː/ |

'hermit', 'rishi' |

| ฦ | /lɯ/ | ลึ | lueng ลึงค์/ฦค์2 /lɯŋ/ ling ລິງ/ລິງຄ໌1 /liŋ/ |

'lingam' |

| ฦๅ | /lɯː/ | ลือ/ลื◌ | luecha ลือชา/ฦๅชา2 /lɯː tɕaː/ luxa ລືຊາ /lɨ́ːsáː/ |

'to be well-known' |

Grammar

Isan words are not inflected, declined, conjugated, making Isan, like Lao and Thai, an analytic language. Special particle words function in lieu of prefixes and suffixes to mark verb tense. The majority of Isan words are monosyllabic, but compound words and numerous other very common words exist that are not. Topologically, Isan is a subject–verb–object (SVO) language, although the subject is often dropped. Word order is an important feature of the language.

Although in formal situations, standard Thai is often used, formality is marked in Isan by polite particles attached to the end of statements, and use of formal pronouns. Compared to Thai, Isan sounds very formal as pronouns are used with greater frequency, which occurs in formal Thai, but is more direct and simple compared to Thai. The ending particles เด้อ (doe, dɤː) or เด (de, deː) function much like ครับ (khrap, kʰráp), used by males, and คะ (kha, kʰaʔ), used by females, in Thai. (Isan speakers sometimes use the Thai particles in place of or after เด้อ or เด.) Negative statements often end in ดอก (dok, dɔ̀ːk), which can also be followed by the particle เด้อ and its variant.

- เพิ่นเฮ็ดปลาแดกเด้อ (phoen het padaek doe, pʰɤn het paːdɛːk dɤː) He makes padaek.

- บ่เป็นหยังดอก (bo pen nyang dok, bɔː peːn ɲaŋ dɔːk) It does not matter.

Nouns

Nouns in Isan are not marked for plurality, gender or case and do not require an indefinite or definite article. Some words, mainly inherited from Sanskrit or Pali, have separate forms for male or female, such as thewa (Template:Lang-tts /tʰéː ʋáː/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN théva), 'god' or 'angel' (masculine) and thewi (Template:Lang-tts /tʰéː ʋíː/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN thévi), 'goddess' or 'angel' (feminine) which derives from masculine deva (Template:Lang-sa /deʋa/ and feminine devī (Template:Lang-sa /deʋiː/). This is also common in names of Sanskrit origin, such as masculine Arun (Template:Lang-tts /áʔ lún/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN Aloun/Aroun) and feminine Aruni (Template:Lang-tts /aʔ lū níː/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN Arouni/Alounee) which derives from Arun Template:Lang-sa /aruɳ/) and Arunī Template:Lang-sa /aruɳiː/, respectively. In native Tai words which usually do not distinguish gender, animals will take the suffixes phu (Template:Lang-tts /pʰȕː/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN phou) or mae (Template:Lang-tts /mɛ̄ː/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN mè). For example, a cat in general is maew (Template:Lang-tts /mɛ́ːw/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN mèo), but a tomcat is maew phou (Template:Lang-tts) and a queen (female cat) is maew mae (Template:Lang-tts), respectively.

Classifiers

| Isan | Category |

| คน (ฅน), kʰon | People in general, except clergy and royals. |

| คัน, kʰan | Vehicles, also used for spoons and forks in Thai. |

| คู่, kʰuː | Pairs of people, animals, socks, earrings, etc. |

| ซบับ, saʔbap | Papers with texts, documents, newspapers, etc. |

| โต, toː | Animals, shirts, letters; also tables and chairs (but not in Lao). |

| กก, kok | Trees. ต้น (or Lao ຕົ້ນ) is used in all three for columns, stalks, and flowers. |

| หน่วย, nuɛj | Eggs, fruits, clouds. ผล (pʰǒn) used for fruits in Thai. |

Verbs are easily made into nouns by adding the prefixes ความ (khwam/kʰwaːm) and การ (kan/kːan) before verbs that express abstract actions and verbs that express physical actions, respectively. Adjectives and adverbs, which can function as complete predicates, only use ความ.

- แข่งม้า (khaengma/kʰɛ̀ːŋ.máː) "to horserace" (v.) nominalizes into การแข่งม้า (kan khaengma/kːan kʰɛ̀ːŋ.máː) "horseracing" (n.)

- เจ็บ (chep/tɕèp) "to hurt (others)" (v.) nominalises into ความเจ็บ (khwam chep/kʰwaːm tɕèp) "hurt (caused by others)" (n.)

- ดี (di, diː) "good" nominalises into ความดี (khwam di, kʰwaːm diː) "goodness" (n.)

Pronouns

Isan traditionally uses the Lao-style pronouns, although in formal contexts, the Thai pronouns are sometimes substituted as speakers adjust to the socially mandated use of Standard Thai in very formal events. Although all the Tai languages are pro-drop languages that omit pronouns if their use is unnecessary due to context, especially in informal contexts, but they are restored in more careful speech. Compared to Thai, Isan and Lao frequently use the first- and second-person pronouns and rarely drop them in speech which can sometimes seem more formal and distant. More common is to substitute pronouns with titles of professions or extension of kinship terms based on age, thus it is very common for lovers or close friends to call each other 'brother' and 'sister' and to address the very elderly as 'grandfather' or 'grandmother'.

To turn a pronoun into a plural, it is most commonly prefixed with mu (Template:Lang-tts /mūː/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN mou) but the variants tu (Template:Lang-tts /tuː/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN tou) and phuak (Template:Lang-tts /pʰûak/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN phouak) are also used by some speakers. These can also be used for the word hao, 'we', in the sense of 'all of us' for extra emphasis. The vulgar pronouns are used as a mark of close relationship, such as long-standing childhood friends or siblings and can be used publicly, but they can never be used outside of these relationships as they often change statements into very pejorative, crude or inflammatory remarks.

| Person | Isan | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | ข้าน้อย khanoi |

/kʰȁː nɔ̑ːj/ | I (formal) |

| ข้อย khoi |

/kʰɔ̏ːj/ | I (common) | |

| กู ku |

/kuː/ | I (vulgar) | |

| หมู่ข้าน้อย mu khanoi |

/mūː kʰȁː nɔ̑ːj/ | we (formal) | |

| เฮา hao |

/hȃo/ | we (common) | |

| หมู่เฮา mu hao |

/mūː hȃo/ | ||

| 2nd | ท่าน | /tʰāːn/ | you (formal) |

| เจ้า chao |

/tɕȃo/ | you (common) | |

| มึง mueng |

/mɨ́ŋ/ | you (vulgar) | |

| หมู่ท่าน mu than |

/mūː tʰāːn/ | you (pl., formal) | |

| หมู่เจ้า chao |

/mūː tɕȃo/ | you (pl., common) | |

| 3rd | เพิ่น phoen |

/pʰə̄n/ | he/she/it (formal) |

| เขา khao |

/kʰăo/ | he/she/it (common) | |

| ลาว lao |

/láːo/ | ||

| มัน man |

/mán/ | he/she/it (common) | |

| ขะเจ้า khachao |

/kʰáʔ tɕȃo/ | they (formal) | |

| หมู่เขา mu khao |

/mūː kʰăo/ | they (common) | |

| หมู่ลาว mu lao |

/mūː láːo/ | ||

Numbers

| Number | Gloss | Number | Gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ๐ ศูนย์ sun |

/sǔːn/ | 0 'zero' nulla |

๒๑ ซาวเอ็ด sao et |

/sáːu ʔét/ | 21 'twenty-one' XXI |

| ๑ หนึ่ง nueng |

/nɨ̄ːŋ/ | 1 'one' I |

๒๒ ซาวสอง sao song |

/sáːu sɔ̆ːŋ/ | 22 'twenty-two' XXII |

| ๒ สอง song |

/sɔ̌ːŋ/ | 2 'two' II |

๒๓ ซาวสาม sao sam |

/sáːu săːm/ | 23 'twenty-three' XXII |

| ๓ สาม sam |

/sǎːm/ | 3 'three' III |

๓๐ สามสิบ sam sip |

/săːm síp/ | 30 thirty XXX |

| ๔ สี่ si |

/sīː/ | 4 four IV |

๓๑ สามสิบเอ็ด sam sip et |

/săːm síp ʔét/ | 31 'thirty-one' XXXI |

| ๕ ห้า ha |

/hȁː/ | 5 'five' V |

๓๒ สามสิบสอง sam sip song |

/săːm síp sɔ̌ːŋ/ | 32 'thirty-two' XXXII |

| ๖ หก hok |

/hók/ | 6 six VI |

๔๐ สี่สิบ si sip |

/sīː síp/ | 40 'forty' VL |

| ๗ เจ็ด chet |

/t͡ɕét/ | 7 'seven' VII |

๕๐ ห้าสิบ ha sip |

/hȁː síp/ | 50 'fifty' L |

| ๘ แปด paet |

/pɛ̏ːt/ | 8 'eight' VIII |

๖๐ หกสิบ hok sip |

/hók síp/ | 60 sixty LX |

| ๙ เก้า kao |

/kȃo/ | 9 nine IX |

๗๐ เจ็ดสิบ chet sip |

/t͡ɕét síp/ | 70 'seventy' LXX |

| ๑๐ สิบ sip |

/síp/ | 10 ten X |

๘๐ แปดสิบ paet sip |

/pɛ̏ːt síp/ | 80 'eighty' LXXX |

| ๑๑ สิบเอ็ด sip et |

/síp ʔét/ | 11 'eleven' XI |

๙๐ เก้าสิบ |

/kȃo síp/ | 90 'nintety' XC |

| ๑๒ สิบสอง |

/síp sɔ̌ːŋ/ | 12 'twelve' XII |

๑๐๐ (หนึ่ง)ฮ้อย |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) hɔ̂ːj/ | 100 'one hundred' C |

| ๑๓ สิบสาม |

/síp săːm/ | 13 'thirteen' XIII |

๑๐๑ (หนึ่ง)ฮ้อยเอ็ด |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) hɔ̂ːj ʔét/ | 101 'one hundred one' CI |

| ๑๔ สิบสี่ |

/síp sīː/ | 14 'fourteen' XIV |

๑๐๐๐ (หนึ่ง)พัน |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) pʰán/ | 1,000 'one thousand' M |

| ๑๕ สิบห้า |

/síp sīː/ | 15 'fifteen' XV |

๑๐๐๐๐ (หนึ่ง)หมื่น |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) mɨ̄ːn/ | 10,000 ten thousand X. |

| ๑๖ สิบหก |

/síp hók/ | 16 'sixteen' XVI |

๑๐๐๐๐๐ (หนึ่ง)แสน |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) sɛ̆ːn/ | 100,000 'one hundred thousand' C. |

| ๑๗ สิบเจ็ด |

/síp t͡ɕét/ | 17 seventeen XVII |

๑๐๐๐๐๐๐ (หนึ่ง)ล้าน |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) lâːn/ | 1,000,000 'one million' |

| ๑๘ สิบแปด |

/síp pɛ́ːt/ | 18 'eighteen' XVIII |

๑๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐ (หนึ่ง)พันล้าน |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) pʰán lâːn/ | 1,000,000,000 'one billion' |

| ๑๗ สิบเก้า |

/síp kȃo/ | 19 'nineteen' XIX |

๑๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐ (หนึ่ง)ล้านล้าน |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) lâːn lâːn/ | 1,000,000,000,000 'one trillion' |

| ๒๐ ซาว(หนึ่ง) sao(nueng) |

/sáːu (nɨ̄ːŋ)/ | 20 'twenty' XX |

๑๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐๐ (หนึ่ง)พันล้านล้าน |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) pʰán lâːn lâːn/ | 1,000,000,000,000,000 'one quadrillion' |

Adjectives and adverbs

There is no general distinction between adjectives and adverbs, and words of this category serve both functions and can even modify each other. Duplication is used to indicate greater intensity. Only one word can be duplicated per phrase. Adjectives always come after the noun they modify; adverbs may come before or after the verb depending on the word. There is usually no copula to link a noun to an adjective.

- เด็กหนุ่ม (dek num, dek num) A young child.

- เด็กหนุ่ม ๆ (dek num num, dek num num) A very young child.

- เด็กหนุ่มที่ไว้ (dek num thi vai, dek num tʰiː vaj) A child who becomes young quickly.

- เด็กหนุ่มที่ไว้ ๆ (dek num thi vai vai, dek num tʰiː vaj vaj) A child who becomes young quickly.

Comparatives take the form "A X กว่า B" (kwa, kwaː), A is more X than B. The superlative is expressed as "A X ที่สุด (thisut, tʰiːsut), A is most X.

- เด็กหนุ่มกว่าผู้แก่ (dek num kwa phukae, dek num kwaː pʰuːkɛː) The child is younger than an old person.

- เด็กหนุ่มที่สุด (dek num thisut, dek num tʰiːsut) The child is youngest.

Because adjectives or adverbs can be used as predicates, the particles that modify verbs are also used.

- เด็กซิหนุ่ม (dek si num, dek siː num) The child will be young.

- เด็กหนุ่มแล้ว (dek num laew, dek num lɛːw) The child was young.

Verbs

Verbs are not declined for voice, number, or tense. To indicate tenses, particles can be used, but it is also very common just to use words that indicate the time frame, such as พรุ่งนี้ (phung ni, pʰuŋ niː) tomorrow or มื้อวานนี้ (meu wan ni, mɯː vaːn niː) yesterday.

Negation: Negation is indicated by placing บ่ (bo, bɔː) before the word being negated.

- อีน้องกินหมากเลน (i nong kin mak len, iːnɔːŋ kin maːk len) Younger sister eats tomatoes.

- อีน้องบ่กินหมากเลน (i nong bao bo kin mak len, iːnɔːŋ bɔː kin maːk len) Younger sister does not eat tomatoes.

Future tense: Future tense is indicated by placing the particles จะ (cha, tɕaʔ) or ซิ (si, siː) before the verb.

- อีน้องจะกินหมากเลน (i nong cha kin mak len, iːnɔːŋ tɕaʔ kin maːk len) Younger sister will eat tomatoes.

- อีน้องซิกินหมากเลน (i nong see kin mak len, iːnɔːŋ siː kin maːk len) Younger sister will eat tomatoes.

Past tense: Past tense is indicated by either placing ได้ (dai, daj) before the verb or แล้ว (laew, lɛːw) after the verb or even using both in tandem for emphasis. แล้ว is the more common one, and can be used to indicate completed actions or current actions of the immediate past. ได้ is often used with negative statements and never for present action.

- อีน้องได้กินหมากเลน (i nong dai kin mak len, iːnɔːŋ daj kin maːk len) Younger sister ate tomatoes.

- อีน้องกินหมากเลนแล้ว (i nong kin mak len laew, iːnɔːŋ kin maːk len lɛːw) Younger sister (just) ate tomatoes.

- อีน้องได้กินหมากเลนแล้ว (i nong dai kin mak len laew, iːnɔːŋ daj kin maːk len lɛːw) Younger sister (definitely) ate tomatoes.

Present progressive: To indicate an ongoing action, กำลัง (kamlang, kam.laŋ) can be used before the verb or อยู่ (yu, juː) after the verb. These can also be combined for emphasis. In Isan and Lao, พวม (phuam, pʰuam) is often used instead of กำลัง.

- อีน้องกำลังกินหมากเลน (i nong kamlang kin mak len, iːnɔːŋ kam.laŋ kin maːk len) Younger sister is eating tomatoes.

- อีน้องกินอยู่หมากเลน (i nong kin yu mak len, iːnɔːŋ kin juː maːk len) Younger sister is eating tomatoes.

- อีน้องพวมกินหมากเลน (i nong phuam kin mak len, iːnɔːŋ pʰuam kin maːk len) Younger sister is eating tomatoes.

The verb 'to be' can be expressed in many ways. In use as a copula, it is often dropped between nouns and adjectives. Compare English She is pretty and Isan สาวงาม (literally lady pretty). There are two copulas used in Isan, as in Lao, one for things relating to people, เป็น (pen, pen), and one for objects and animals, แม่น (maen, mɛːn).

- นกเป็นหมอ (Nok pen mo, Nok pe mɔː) Nok is a doctor.

- อันนี้แม่นสามล้อ (an née maen sam lo, an niː mɛːn saːm lɔː) This is a pedicab.

Questions and answers

Unlike English, which indicates questions by a rising tone, or Spanish, which changes the order of the sentences to achieve the same result, Isan uses question-tag words. The use of question words makes use of the question mark (?) redundant in Isan.

General yes/no questions end in บ่ (same as บ่, "no, not").

- สบายดีบ่ (sabai di bo, saʔbaj diː bɔː) Are you well?

Other question words

- จั่งใด (changdai, tɕaŋdaj) or หยัง (nyang, ɲaŋ) เฮ็ดจั่งใด (het changdai, het tɕaŋ.daj) What are you doing?

- ใผ (phai, pʰaj) ใผขายไขไก่ (phai khai khai kai, pʰaj kʰaːj kʰaj kaj) Who sells chicken eggs?

- ใส (sai, saj) Where? ห้องน้ำอยู่ใส (hong nam yu sai, hɔːŋnam juː saj) Where is the toilet?

- อันใด (andai, andaj) Which? เจ้าได้กินอันใด (chao kin andai, tɕaw gin an.daj) Which one did you eat?

- จัก (chak, tɕak) How many? อายุจักปี (ayu chak pi, aːju tɕak piː) How old are you?

- ท่อใด (thodai, tʰɔːdaj) How much? ควายตัวบทท่อใด (khwai ɗua bot thodai, kʰwaj bot tʰɔːdaj) How much is that buffalo over there?

- แม่นบ่ (maen bo, mɛːn bɔː) Right?, Is it? เต่าไวแม่นบ่ (Tao vai maen bo, ɗaw vai mɛːn bɔː) Turtles are fast, right?

- แล้วบ่ (laew bo, lɛːw bɔː) Yet?, Already? เขากลับบ้านแล้วบ่ (khao kap laew bo, kʰaw gap baːn lɛːw bɔː) Did he go home already?

- หรือบ่ (loe bo, lɤː bɔː) Or not? เจ้าหิวข้าวหรือบ่ (chao hio khao loe bo, tɕaw hiw kʰaw lɤː bɔː) Are you hungry or not?

Answers to questions usually just involve repetition of the verb and any nouns for clarification.

- Question: สบายดีบ่ (sabai di bo, saʔbaj diː bɔː) Are you well?

- Response: สบายดี (sabai di, saʔbaj diː) I am well or บ่สบาย (bo sabai, bɔː saʔbaj) I am not well.

Words asked with a negative can be confusing and should be avoided. The response, even though without the negation, will still be negated due to the nature of the question.

- Question: บ่สบายบ่ (bo sabai bo, bɔː saʔbaːj bɔː) Are you not well?

- Response: สบาย (sabai, saʔbaj) I am not well or บ่สบาย (bo sabai, bɔː saʔbaːj ) I am well.

Vocabulary

The Tai languages of Thailand and Laos share a large corpus of cognate, native vocabulary. They also share many common words and neologisms that were derived from Sanskrit, Pali, Mon and Khmer and other indigenous inhabitants to Indochina. However, there are traits that distinguish Isan both from Thai and its Lao parent language.

Isan is clearly differentiated from Thai by its Lao intonation and vocabulary. However, Isan differs from Lao in that the former has more English and Chinese loanwords, via Thai, not to mention large amounts of Thai influence. The Lao adopted French and Vietnamese loanwords as a legacy of French Indochina. Other differences between Isan and Lao include terminology that reflects the social and political separation since 1893 as well as differences in neologisms created after this. These differences, and a few very small deviations for certain common words, do not, however, diminish nor erase the Lao characters of the language.

| Common vocabulary | Rachasap | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isan | Thai | Lao | Khmer | English | Isan | Thai | Lao | Khmer | English |

| กระแทะ kratae, /rɔteh/ |

กระแทะ kratae, /rɔteh/ |

ກະແທະ katè, /rɔteh/ |

រទេះ rôthéh, /rɔteh/ |

'oxcart' | บรรทม banthom, /bàn tʰóm/ |

บรรทม banthom, /ban tʰom/ |

ບັນທົມ banthôm, /bàn tʰóm/ |

បន្ទំ banthum, /bɑn tum/ |

'to sleep' |

| เดิน doen, /dɤːn/ |

เดิน doen, /dɤːn/ |

ເດີນ deun, /dɤ̀ːn/ |

ដើរ daeu, /daə/ |

'to walk' | ตรัส trat, /tāt/ |

ตรัส trat, /tràt/ |

ຕັດ tat, /tāt/ |

ត្រាស់ trah, /trah/ |

'to speak' |

| พนม phanom, /pʰāʔ nóm/ |

พนม phanom, /pʰāʔ nóm/ |

ພະນົມ/ພນົມ phanôm, /pʰaʔ nom/ |

ភ្នំ phnum/phnom, /pʰnum/ |

'mountain' | ขนอง khanong, /kʰáʔ nɔ̌ːŋ/ |

ขนอง khanong, /kʰàʔ nɔ̌ːŋ/ |

ຂະໜອງ/ຂນອງ khanong, /kʰáʔ nɔ̆ːŋ/ |

ខ្នង khnâng, /knɑːŋ/ |

'back', 'dorsal ridge' |

| ถนน thanon, /tʰáʔ nǒn/ |

ถนน thanôn, /tʰaʔ nǒn/ |

ຖະໜົນ/ຖໜົນ thanôn, /tʰáʔ nǒn/ |

ថ្នល់ tnâl, /tnɑl/ |

'road' | ศอ so, /sɔ̆ː/ |

ศอ so, /sɔ̆ː/ |

ສໍ so, /sɔ̆ː/ |

សូ[រង] sŭ[rang], /suː [rɑːng]/ |

'neck' |

| English | Isan | Lao | Thai | English | Isan | Lao | Thai |

| "ice" | น้ำแข็ง, nâm kʰɛ̌ːŋ | ນ້ຳກ້ອນ, nâm kɔ̂ːn5 | น้ำแข็ง, náːm kʰɛ̌ŋ | "plain" (adj.) | เปล่า, paw | ລ້າ, lâː | เปล่า, plàːw |

| "necktie" | เน็กไท, nēk tʰáj | ກາຣະວັດ, kaː rāʔ vát6 | เน็กไท, nék tʰáj | "province" | จังหวัด, t͡ʃàŋ vát | ແຂວງ, kʰwɛ̌ːŋ7 | จังหวัด, tɕaŋ wàt |

| "wine" | ไวน์, váj | ແວງ vɛ́ːŋ8 | ไวน์, waːj | "pho" | ก๋วยเตี๋ยว, kuǎj tǐaw | ເຝີ, fɤ̌ː9 | ก๋วยเตี๋ยว, kuǎj tǐaw |

| "January" | มกราคม, mōk káʔ ráː kʰóm | ມັງກອນ, máŋ kɔ̀ːn | มกราคม, mók kàʔ raː kʰom | "paper" | กะดาษ, káʔ dȁːt | ເຈັ້ຽ, t͡ɕìa | กระดาษ, kràʔ dàːt |

| "window" | หน้าต่าง, nȁː tāːŋ | ປ່ອງຢ້ຽມ, pɔ̄ːŋ jîam | หน้าต่าง, nâː tàːŋ | "book" | หนังสือ, nǎŋ.sɨ̌ː | ປຶ້ມ, pɨ̂m | หนังสือ, nǎng.sɯ̌ː |

| "motorcycle" | มอเตอร์ไซค์, mɔ́ː tɤ̀ː sáj | ຣົຖຈັກ, rōt t͡ʃák | มอเตอร์ไซค์, mɔː tɤː saj10 | "butter" | เนย, /nɤ´ːj/ | ເບີຣ໌, /bɤ`ː/11 | เนย, /nɤːj/ |

- ^5 Formerly น้ำก้อน, but this is now archaic/obsolete.

- ^6 From French cravate, /kra vat/

- ^7 Thai and Isan use แขวง to talk about provinces of Laos.

- ^8 From French vin (vɛ̃) as opposed to Thai and Isan ไวน์ from English wine.

- ^9 From Vietnamese phở /fə̃ː/.

- ^10 From English "motorcycle".

- ^11 From French beurre, /bøʁ/

A small handful of lexical items are unique to Isan and not commonly found in standard Lao, but may exist in other Lao dialects. Some of these words exist alongside more typically Lao or Thai usages.

| English | Isan | Lao | Thai | Isan Variant |

| "to work" | เฮ็ดงาน, hēt ŋáːn | ເຮັດວຽກ hēt vîak12 | ทำงาน, tʰam ŋaːn | - |

| "papaya" | บักหุ่ง, bák hūŋ | ໝາກຫຸ່ງ, mȁːk hūŋ | มะละกอ, màʔ làʔ kɔː | - |

| "fried beef" | ทอดซี้น, tʰɔ̂ːt sîːn | ຂົ້ວຊີ້ນ, kʰȕa sîːn | เนื้อทอด, nɯ´ːa tʰɔ̂ːt | - |

| "hundred" | ร้อย, lɔ̂ːj | ຮ້ອຍ, hɔ̂ːj | ร้อย, rɔ́ːj | - |

| "barbecued pork" | หมูปิ้ง, mǔː pîːŋ | ປີ້ງໝູ, pîːŋ mǔː | หมูย่าง, mǔː jâːŋ | - |

| 'ice cream' | ไอติม, /ʔaj tím/, ai tim | ກາແລ້ມ, /kaː lɛ̂ːm/, kalèm | ไอศกรีม, /ʔaj sàʔ kriːm/, aisakrim | N/A |

| 'to be well' | ซำบาย, /sám báːj/, sambai | ສະບາຍ/Archaic ສະບາຽ, /sáʔ báːj/, sabai | สบาย, /sàʔ baːj/, sabai | สบาย, /sáʔ báːj/, sabai |

| 'fruit' | บัก, /bák/, bak | ໝາກ/ຫມາກ, /mȁːk/, mak | ผล, /pʰŏn/, phon | หมาก, /mȁːk/, mak |

| 'lunch' | เข้าสวย, /kʰȁo sŭːəj/, khao suay | ອາຫານທ່ຽງ, /ʔaː hăːn tʰīaŋ/, ahane thiang | อาหารกลางวัน, /ʔaː hăːn klaːŋ wan/, ahan klangwan | เข้าเที่ยง, /kʰȁo tʰīaŋ/, khao thiang |

| 'traditional animist ceremony' | บายศรี, /baːj sĭː/, baisri | ບາສີ, /baː sĭː/, basi | บวงสรวง, /buaŋ suaŋ /, buang suang | บายศรีสู่ขวัญ, /baːj sĭː sūː kʰŭan/, baisri su khwan |

Dialects

Although Isan is treated separately from the Lao language of Laos due to its use of the Thai script, political sensitivity and the influence of the Thai language, dialectal isoglosses crisscross the Mekong River, mirroring the downstream migration of the Lao people as well as the settlement of Isan from the east to west, as people were forced to the right bank. Isan can be broken up into at least fourteen varieties, based on small differentiations in tonal quality and distribution as well as small lexical items, but these can be grouped into the same five dialectal regions of Laos. As a result of the movements, Isan varieties are often more similar to the Lao varieties spoken on the opposite banks of the Mekong than to other Isan people up- or downstream although Western Lao, formed from the merger of peoples from different Lao regions, does not occur in Laos and is only found in Isan.[5][33][34]

Isan may have had historical leveling processes. The settlement of the region's interior areas led to dialect mixing and the development of transitional areas. The Vientiane dialect also likely had a major role in bringing Isan varieties closer. The provinces of Loei, Nong Khai and Bueang Kan border areas of Laos where Vientiane Lao is spoken, and together with Nong Bua Lamphu and much of Udon Thani, were long settled by Lao speakers of these dialects from the time of Lan Xang as well as the Kingdom of Vientiane. The destruction of Vientiane and the forced movement of almost the entire population of the city and surrounding region after the Lao rebellion greatly increased the population of Isan, with these Lao people settled across the region.[35]

| Dialect | Lao Provinces | Thai Provinces |

| Vientiane Lao | Vientiane, Vientiane Prefecture, Bolikhamxay and southern Xaisômboun | Nong Khai, Nong Bua Lamphu, Chaiyaphum, Udon Thani, portions of Yasothon, Bueng Kan, Loei and Khon Kaen (Khon Chaen) |

| Northern Lao Louang Phrabang Lao |

Louang Phrabang, Xaignbouli, Oudômxay, Phôngsali, Bokèo and Louang Namtha, portions of Houaphan | Loei, portions of Udon Thani, Khon Kaen(Khon Chaen), also Phitsanulok and Uttaradit (outside Isan) |

| Northeastern Lao Phuan (Phouan) Lao |

Xiangkhouang, portions of Houaphan and Xaisômboun | Scattered in isolated villages of Chaiyaphum, Sakon Nakhon, Udon Thani, Bueng Kan, Nong Khai and Loei[a] |

| Central Lao (ลาวกลาง, ລາວກາງ) | Khammouan and portions of Bolikhamxay and Savannakhét | Mukdahan, Sakon Nakhon, Nakhon Phanom, Mukdahan; portions of Nong Khai and Bueng Kan |

| Southern Lao | Champasak, Saravan, Xékong, Attapeu, portions of Savannakhét | Ubon Ratchathani (Ubon Ratsathani), Amnat Charoen, portions of Si Sa Ket, Surin, Nakhon Ratchasima (Nakhon Ratsasima), and Yasothon[b] |

| Western Lao | * Not found in Laos | Kalasin, Roi Et (Hoi Et), Maha Sarakham, portions of Phetchabun (Phetsabun), Chaiyaphum (Saiyaphum) and Nakhon Ratchasima (Nakhon Ratsasima) |

Writing systems

Tai Noi script

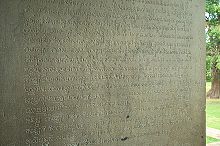

The original writing system was the Akson Tai Noi (Template:Lang-tts /ák sɔ̆ːn tʰáj nɔ̑ːj/, cf. Template:Lang-lo BGN/PCGN Akson Tai Noy), 'Little Tai alphabet' or To Lao (Template:Lang-tts /to: láːo/, cf. Template:Lang-lo), which in contemporary Isan and Lao would be Tua Lao (Template:Lang-tts /tuːa láːo/ and Template:Lang-lo, respectively, or 'Lao letters.' In Laos, the script is referred to in academic settings as the Akson Lao Deum (Template:Lang-lo /ák sɔ̆ːn láːo d̀ɤːm/, cf. Template:Lang-tts RTGS Akson Lao Doem) or 'Original Lao script.' The contemporary Lao script is a direct descendant and has preserved the basic letter shapes. The similarity between the modern Thai alphabet and the old and new Lao alphabets is because both scripts derived from a common ancestral Tai script of what is now northern Thailand which was an adaptation of the Khmer script, rounded by the influence of the Mon script, all of which are descendants of the Pallava script of southern India.[25]

Thai alphabet

The ban on the Tai Noi script in the 1930s led to the adoption of writing in Thai with the Thai script. Very quickly, the Isan people adopted an ad hoc system of using Thai to record the spoken language, using etymological spelling for cognate words but spelling Lao words not found in Thai, and with no known Khmer or Indic etymology, similarly to as they would be in the Lao script. This system remains in informal use today, often seen in letters, text messages, social media posts, lyrics to songs in the Isan language, transcription of Isan dialogue and personal notes.

'Lao'-ized spelling

There are two aspects of Lao phonology inherited in Isan that native speakers will substitute different letters to represent the proper sound.

Proto-Southwestern Tai initial /r/ > /h/

- Lao 'ຣ' /r/ and 'ຮ' /h/

- Isan 'ร' /r/ and 'ฮ' /h/

- Thai ron (ร้อน /rɔ́ːn/), 'hot' > Isan hon (ฮ้อน, ຮ້ອນ, /hɔ̑ːn/)

Loss of Proto-Southwestern Tai /tɕʰ/ by merger with /s/ in Lao

- Lao 'ຊ' /s/, romanized as 'x'