Dental abscess: Difference between revisions

WP Ludicer (talk | contribs) |

Windows fixed the stokes |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tooth Abscess}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tooth Abscess}} |

||

[[Category:Acquired tooth disorders]] |

|||

[[Category:Infectious diseases]] |

[[Category:Infectious diseases]] |

||

Revision as of 09:11, 14 July 2021

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (January 2018) |  |

| Dental abscess | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dentoalveolar abscess, tooth abscess, root abscess |

| |

| A decayed, broken down tooth, which has undergone pulpal necrosis. A periapical abscess (i.e. around the apex of the tooth root) has then formed and pus is draining into the mouth via an intraoral sinus (gumboil). | |

| Specialty | Dentistry |

A dental abscess is a localized collection of pus associated with a tooth. The most common type of dental abscess is a periapical abscess, and the second most common is a periodontal abscess. In a periapical abscess, usually the origin is a bacterial infection that has accumulated in the soft, often dead, pulp of the tooth. This can be caused by tooth decay, broken teeth or extensive periodontal disease (or combinations of these factors). A failed root canal treatment may also create a similar abscess.

A dental abscess is a type of odontogenic infection, although commonly the latter term is applied to an infection which has spread outside the local region around the causative tooth.

Classification

The main types of dental abscess are:

- Periapical abscess: The result of a chronic, localized infection located at the tip, or apex, of the root of a tooth.[1]

- Periodontal abscess: begins in a periodontal pocket (see: periodontal abscess)

- Gingival abscess: involving only the gum tissue, without affecting either the tooth or the periodontal ligament (see: periodontal abscess)

- Pericoronal abscess: involving the soft tissues surrounding the crown of a tooth (see: Pericoronitis)

- Combined periodontic-endodontic abscess: a situation in which a periapical abscess and a periodontal abscess have combined (see: Combined periodontic-endodontic lesions).

Signs and symptoms

The pain is continuous and may be described as extreme, growing, sharp, shooting, or throbbing. Putting pressure or warmth on the tooth may induce extreme pain. The area may be sensitive to touch and possibly swollen as well. This swelling may be present at either the base of the tooth, the gum, and/or the cheek, and sometimes can be reduced by applying ice packs.

An acute abscess may be painless but still have a swelling present on the gum. It is important to get anything that presents like this checked by a dental professional as it may become chronic later.

In some cases, a tooth abscess may perforate bone and start draining into the surrounding tissues creating local facial swelling. In some cases, the lymph glands in the neck will become swollen and tender in response to the infection. It may even feel like a migraine as the pain can transfer from the infected area. The pain does not normally transfer across the face, only upwards or downwards as the nerves that serve each side of the face are separate.

Severe aching and discomfort on the side of the face where the tooth is infected is also fairly common, with the tooth itself becoming unbearable to touch due to extreme amounts of pain.

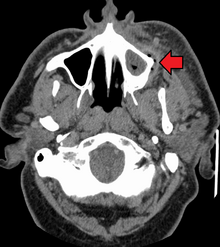

Diagnostic approach

A periodontal abscess may be difficult to distinguish from a periapical abscess. Indeed, sometimes they can occur together.[2] Since the management of a periodontal abscess is different from that of a periapical abscess, this differentiation is important to make.

- If the swelling is over the area of the root apex, it is more likely to be a periapical abscess; if it is closer to the gingival margin, it is more likely to be a periodontal abscess.

- Similarly, in a periodontal abscess pus most likely discharges via the periodontal pocket, whereas a periapical abscess generally drains via a parulis nearer to the apex of the involved tooth.[2]

- If the tooth has pre-existing periodontal disease, with pockets and loss of alveolar bone height, it is more likely to be a periodontal abscess; whereas if the tooth has relatively healthy periodontal condition, it is more likely to be a periapical abscess.

- In periodontal abscesses, the swelling usually precedes the pain, and in periapical abscesses, the pain usually precedes the swelling.[2]

- A history of toothache with sensitivity to hot and cold suggests previous pulpitis, and indicates that a periapical abscess is more likely.

- If the tooth which gives normal results on pulp sensibility testing, is free of dental caries and has no large restorations; it is more likely to be a periodontal abscess.

- A dental radiograph is of little help in the early stages of a dental abscess, but later usually the position of the abscess, and hence indication of endodontal/periodontal etiology can be determined. If there is a sinus, a gutta percha point is sometimes inserted before the x-ray in the hope that it will point to the origin of the infection.

- Generally, periodontal abscesses will be more tender to lateral percussion than to vertical, and periapical abscesses will be more tender to apical percussion.[2]

Treatment

Successful treatment of a dental abscess centers on the reduction and elimination of the offending organisms. This can include treatment with antibiotics[3] and drainage, however, it has become widely recommended that dentists should improve the antibiotic prescribing practices, by limiting the prescriptions to the acute cases that suffer from the severe signs of spreading infection,[4][5] in an attempt to overcome the development of antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains in the population. A 2018 Cochrane review has found insufficient evidence to rule out if patients with acute dental abscesses can benefit from antibiotic prescriptions.[6]

If the tooth can be restored, root canal therapy can be performed. Non-restorable teeth must be extracted, followed by curettage of all apical soft tissue.

Unless they are symptomatic, teeth treated with root canal therapy should be evaluated at 1- and 2-year intervals after the root canal therapy to rule out possible lesional enlargement and to ensure appropriate healing.

Abscesses may fail to heal for several reasons:

- Cyst formation

- Inadequate root canal therapy

- Vertical root fractures

- Foreign material in the lesion

- Associated periodontal disease

- Penetration of the maxillary sinus

Following conventional, adequate root canal therapy, abscesses that do not heal or enlarge are often treated with surgery and filling the root tips; and will require a biopsy to evaluate the diagnosis.[7]

Complications

If left untreated, a severe tooth abscess may become large enough to perforate bone and extend into the soft tissue eventually becoming osteomyelitis and cellulitis respectively. From there it follows the path of least resistance and may spread either internally or externally. The path of the infection is influenced by such things as the location of the infected tooth and the thickness of the bone, muscle and fascia attachments.

External drainage may begin as a boil which bursts allowing pus drainage from the abscess, intraorally (usually through the gum) or extraorally. Chronic drainage will allow an epithelial lining to form in this communication to form a pus draining canal (fistula). Sometimes this type of drainage will immediately relieve some of the painful symptoms associated with the pressure.

Internal drainage is of more concern as growing infection makes space within the tissues surrounding the infection. Severe complications requiring immediate hospitalization include Ludwig's angina, which is a combination of growing infection and cellulitis which closes the airway space causing suffocation in extreme cases. Also infection can spread down the tissue spaces to the mediastinum which has significant consequences on the vital organs such as the heart. Another complication, usually from upper teeth, is a risk of sepsis from connecting into blood vessels, brain abscess (extremely rare), or meningitis (also rare).

Depending on the severity of the infection, the sufferer may feel only mildly ill, or may in extreme cases require hospital care.

See also

References

- ^ Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ^ a b c d Fan KF, Jones J (2009). OSCEs for dentistry (2nd, new and updated ed.). 2nd: PasTest Ltd. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-905635-50-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Dental abscess - Management". Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Dar-Odeh NS, Abu-Hammad OA, Al-Omiri MK, Khraisat AS, Shehabi AA (July 2010). "Antibiotic prescribing practices by dentists: a review". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 6: 301–6. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s9736. PMC 2909496. PMID 20668712.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Oberoi SS, Dhingra C, Sharma G, Sardana D (February 2015). "Antibiotics in dental practice: how justified are we". International Dental Journal. 65 (1): 4–10. doi:10.1111/idj.12146. PMID 25510967.

- ^ Cope, Anwen L; Francis, Nick; Wood, Fiona; Chestnutt, Ivor G (27 September 2018). Cochrane Oral Health Group (ed.). "Systemic antibiotics for symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD010136. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010136.pub3. PMC 6513530. PMID 30259968.

- ^ Neville BW (1995). Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology (1st ed.). Saunders. pp. 104–5. ISBN 978-1-4160-3435-3.