Men in Black (1997 film): Difference between revisions

Blackzabdi (talk | contribs) Tag: Reverted |

m Undid revision 1047499369 by Blackzabdi (talk) |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

The film is loosely based on [[Lowell Cunningham]] and [[Sandy Carruthers]]'s comic book ''[[The Men in Black (comics)|The Men in Black]]''. Producers [[Walter F. Parkes]] and [[Laurie MacDonald]] optioned the rights to ''The Men in Black'' in 1992, and hired [[Ed Solomon]] to write a very faithful script. Parkes and MacDonald wanted [[Barry Sonnenfeld]] as director because he had helmed the darkly humorous ''[[The Addams Family (1991 film)|The Addams Family]]'' and its sequel ''[[Addams Family Values]]''. However, Sonnenfeld was attached to ''[[Get Shorty (film)|Get Shorty]]'' (1995), so they instead approached [[Les Mayfield]] to direct, as they had heard about the positive reception to his remake of ''[[Miracle on 34th Street (1994 film)|Miracle on 34th Street]]''; they actually saw the film later and decided he was inappropriate.{{citation needed|date=December 2011}} As a result, ''Men in Black'' was delayed so as to allow Sonnenfeld to make it his next project after ''Get Shorty''.<ref name=hughes>{{cite book | author = David Hughes | title = Comic Book Movies | publisher = [[Virgin Books]] | year = 2003 | location = London | pages = 123–129 | isbn = 0-7535-0767-6}}</ref> |

The film is loosely based on [[Lowell Cunningham]] and [[Sandy Carruthers]]'s comic book ''[[The Men in Black (comics)|The Men in Black]]''. Producers [[Walter F. Parkes]] and [[Laurie MacDonald]] optioned the rights to ''The Men in Black'' in 1992, and hired [[Ed Solomon]] to write a very faithful script. Parkes and MacDonald wanted [[Barry Sonnenfeld]] as director because he had helmed the darkly humorous ''[[The Addams Family (1991 film)|The Addams Family]]'' and its sequel ''[[Addams Family Values]]''. However, Sonnenfeld was attached to ''[[Get Shorty (film)|Get Shorty]]'' (1995), so they instead approached [[Les Mayfield]] to direct, as they had heard about the positive reception to his remake of ''[[Miracle on 34th Street (1994 film)|Miracle on 34th Street]]''; they actually saw the film later and decided he was inappropriate.{{citation needed|date=December 2011}} As a result, ''Men in Black'' was delayed so as to allow Sonnenfeld to make it his next project after ''Get Shorty''.<ref name=hughes>{{cite book | author = David Hughes | title = Comic Book Movies | publisher = [[Virgin Books]] | year = 2003 | location = London | pages = 123–129 | isbn = 0-7535-0767-6}}</ref> |

||

Much of the initial script drafts were set underground, with locations ranging from [[Kansas]] to [[Washington, D.C.]] and [[Nevada]]. Sonnenfeld decided to change the location to New York City, because the director felt New Yorkers would be tolerant of aliens who behaved oddly while disguised. He also felt much of the city's structures resembled [[flying saucer]]s and [[Space vehicle|rocket ships]].<ref name=hughes/> One of the locations Sonnenfeld thought perfect for the movie was a giant ventilation structure for the [[Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel]], which became the outside of the MIB headquarters. |

Much of the initial script drafts were set underground, with locations ranging from [[Kansas]] to [[Washington, D.C.]] and [[Nevada]]. Sonnenfeld decided to change the location to New York City, because the director felt New Yorkers would be tolerant of aliens who behaved oddly while disguised. He also felt much of the city's structures resembled [[flying saucer]]s and [[Space vehicle|rocket ships]].<ref name=hughes/> One of the locations Sonnenfeld thought perfect for the movie was a giant ventilation structure for the [[Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel]], which became the outside of the MIB headquarters.<ref name=met/> |

||

the ate |

|||

<ref name=met/> |

|||

===Filming=== |

===Filming=== |

||

Revision as of 04:19, 1 October 2021

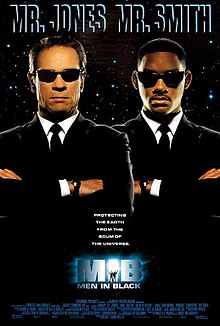

| Men in Black | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Barry Sonnenfeld |

| Screenplay by | Ed Solomon |

| Story by | Ed Solomon |

| Based on | The Men in Black by Lowell Cunningham |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Don Peterman |

| Edited by | Jim Miller |

| Music by | Danny Elfman |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Releasing |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $90 million[1] |

| Box office | $589.4 million[1] |

Men in Black (stylized as MIB: Men in Black) is a 1997 American science fiction action comedy film directed by Barry Sonnenfeld, produced by Walter F. Parkes and Laurie MacDonald and written by Ed Solomon. Loosely based on The Men in Black comic book series created by Lowell Cunningham and Sandy Carruthers, the film stars Tommy Lee Jones and Will Smith as two agents of a secret organization called the Men in black, who supervise extraterrestrial lifeforms who live on Earth and hide their existence from ordinary humans. The film featured the creature effects and makeup of Rick Baker and visual effects by Industrial Light & Magic.

The film was released in the United States on July 2, 1997, by Columbia Pictures, and grossed over $589.3 million worldwide against a $90 million budget, becoming the year's third highest-grossing film. It received positive reviews, with critics praising its script, humor, set pieces, visual effects, and the performances of Jones and Smith. The film received three Academy Award nominations—Best Art Direction, Best Original Score, and Best Makeup—winning the latter award.

The film spawned two sequels, Men in Black II (2002) and Men in Black 3 (2012); a spin-off film, Men in Black: International (2019); and a 1997–2001 animated series.

Plot

After a government agency makes first contact with aliens in 1961, alien refugees live in secret on Earth by disguising themselves as humans. Men in Black (MIB) is a secret agency that polices these aliens, protects Earth from extraterrestrial threats, and uses memory-erasing neuralyzers to keep alien activity a secret. MIB agents have their former identities erased while retired agents are neuralyzed. After an operation to arrest an alien criminal near the Mexican border by Agents K and D, the latter decides that he is too old for his job, prompting the former to neuralyze him so he can retire.

Meanwhile, NYPD undercover officer James Darrell Edwards III pursues a fast and agile alien criminal in human disguise into the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Impressed, K interviews James about his encounter, then neuralyzes him and leaves him a business card with an address. Edwards goes to the address and undergoes a series of tests, for which he finds unorthodox solutions, including a rational hesitation in a targeting test. While the other candidates, who are military-grade, are neuralyzed, K offers Edwards a position with the MIB. Edwards accepts and his identity and civilian life are erased as he becomes Agent J.

In upstate New York, an alien illegally crash-lands on Earth, kills a farmer named Edgar, and uses his skin as a disguise. Tasked with finding a device called "The Galaxy", the Edgar alien tracks down two aliens (disguised as humans) who are supposed to have it in their possession. He kills them and takes a container from them but finds only diamonds inside. After learning about the incident, K investigates the crash landing and concludes that Edgar's skin was taken by a "bug", a species of aggressive cockroach-like aliens. He and J head to a morgue to examine the bodies the bug killed. Inside one body (which turns out to be a piloted robot) they discover a dying Arquillian alien, who says that "to prevent war, the galaxy is on Orion's belt". The alien, who used the name Rosenberg, was a member of the Arquillian royal family; K fears his death may spark a war.

MIB informant Frank the Pug explains that the missing galaxy is a massive energy source in the form of an actual galaxy housed in a small jewel. J deduces that the galaxy is hanging on the collar of Rosenberg's cat, Orion, which refuses to leave the body at the morgue. J and K arrive just as the bug takes the galaxy and kidnaps the coroner, Laurel Weaver. Meanwhile, an Arquillian battleship delivers an ultimatum to the MIB: return the galaxy within a "galactic standard week", in an hour of Earth time, or they will destroy Earth.

The bug arrives at the observation towers of the 1964 New York World's Fair New York State Pavilion at Flushing Meadows, which disguise two real flying saucers. Once there, Laurel escapes the bug's clutches. It activates one of the saucers and tries to leave Earth, but K and J shoot it down and the ship crashes into the Unisphere. The bug sheds Edgar's skin and swallows J and K's guns. K provokes it until he too is swallowed. The bug tries to escape on the other ship, but J stalls it by crushing cockroaches, which makes it angry. K blows the bug apart from the inside, having found his gun inside its stomach. J and K recover the galaxy, only for the still living upper half of the bug to pounce on them from behind, but Laurel kills it with J's gun.

At the MIB headquarters, K tells J that he has not been training him as a partner, but a replacement. K bids J farewell before J neuralyzes him at his request; K returns to his civilian life, and Laurel becomes J's new partner, L. During the final shot it is revealed that the entire Milky Way is housed inside of a marble-like jewel.

Cast

- Tommy Lee Jones as Kevin Brown / Agent K: J's grizzled and humorless mentor. Clint Eastwood turned down the part, while Jones only accepted the role after Steven Spielberg promised the script would improve, based on his respect for Spielberg's track record. He had been disappointed with the first draft, which he reportedly said "stank", feeling it did not capture the tone of the comic.[2]

- Will Smith as James Darrell Edwards III / Agent J: A former NYPD detective, newly recruited to the MIB. Smith was cast because Barry Sonnenfeld's wife was a fan of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. Sonnenfeld also liked his performance in Six Degrees of Separation.[2] Chris O'Donnell turned down the role because he found the role of a new recruit too similar to Dick Grayson, whom he played in Batman Forever and Batman & Robin.[3] David Schwimmer also turned down the part.[2] Like Jones, Smith said he accepted the role after meeting with Spielberg and cited his success as a producer.

- Linda Fiorentino as Dr. Laurel Weaver / Agent L: A deputy medical examiner, and later J's partner.

- Vincent D'Onofrio as the Bug: A giant alien insect that eats a farmer named Edgar and uses his skin and clothes as a disguise. He comes to earth to kidnap the Galaxy and use it to destroy the Arquillians. John Turturro and Bruce Campbell were both offered the role, but they turned it down, due to scheduling conflicts.[2]

- D'Onofrio also portrays Edgar.

- Rip Torn as Chief Zed: The head of the MIB.

- Tony Shalhoub as Jack Jeebs: An alien arms dealer who runs a pawn shop as a front.

- Siobhan Fallon Hogan as Beatrice: Edgar's abused wife.

- Mike Nussbaum as Gentle Rosenberg: An Arquillian jeweler who is the guardian of "the Galaxy".

- Jon Gries as Van Driver

- Sergio Calderón as Jose

- John Alexander as Mikey: An alien who poses as a Mexican being snuck across the border.

- Patrick Breen as Mr. Redgick

- Becky Ann Baker as Mrs. Redgick

- Carel Struycken as Arquillian

- Fredric Lehne as Agent Janus

- Kent Faulcon as Jake Jensen

- Richard Hamilton as Agent D: K's former partner who retires after deciding he is too old for the job.

- David Cross as Newton

- Sean Whalen as Passport Officer

- Ray Park as the Cephalopoid (alien that can climb walls, run super fast, and has second eyelids that are possibly gills to breath in Earth atmosphere.)

Voices/Puppeteers

- Tim Blaney as Frank the Pug: A smart-talking pug-like alien.

- Mark Setrakian as Rosenberg Alien

- Brad Abrell, Thom Fountain, Carl J. Johnson and Drew Massey as the Worm Guys: A quartet of worm-like aliens that work for Men in Black.

Production

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2011) |

Development

The film is loosely based on Lowell Cunningham and Sandy Carruthers's comic book The Men in Black. Producers Walter F. Parkes and Laurie MacDonald optioned the rights to The Men in Black in 1992, and hired Ed Solomon to write a very faithful script. Parkes and MacDonald wanted Barry Sonnenfeld as director because he had helmed the darkly humorous The Addams Family and its sequel Addams Family Values. However, Sonnenfeld was attached to Get Shorty (1995), so they instead approached Les Mayfield to direct, as they had heard about the positive reception to his remake of Miracle on 34th Street; they actually saw the film later and decided he was inappropriate.[citation needed] As a result, Men in Black was delayed so as to allow Sonnenfeld to make it his next project after Get Shorty.[2]

Much of the initial script drafts were set underground, with locations ranging from Kansas to Washington, D.C. and Nevada. Sonnenfeld decided to change the location to New York City, because the director felt New Yorkers would be tolerant of aliens who behaved oddly while disguised. He also felt much of the city's structures resembled flying saucers and rocket ships.[2] One of the locations Sonnenfeld thought perfect for the movie was a giant ventilation structure for the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel, which became the outside of the MIB headquarters.[4]

Filming

Principal photography began in March 1996. Many last-minute changes ensued during production. First, the scene where James Edwards chasing a disguised alien was to be filmed at Lincoln Center, but the New York Philharmonic decided to charge the filmmakers for using their buildings, prompting Sonnenfeld to film the scene at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum instead. Then, five months into the shoot, Sonnenfeld decided that the original ending, with a humorous existential debate between Agent J and the Bug, was unexciting and lacking the action that the rest of the film had.[4] Five potential replacements were discussed. One of these had Laurel Weaver being neuralyzed and K remaining an agent.[2] Eventually it boiled down to the Bug eating K and fighting J, replacing the animatronic Bug Rick Baker's crew had developed with a computer-generated Bug with an appearance closer to a cockroach. The whole action sequence cost an extra $4.5 million to the filmmakers.[4]

Further changes were made during post-production to simplify the plotline involving the possession of the tiny galaxy. The Arquillians would hand over the galaxy to the Baltians, ending a long war. The Bugs need to feed on the casualties and steal the galaxy in order to continue the war. Through changing of subtitles, the images on M.I.B.'s main computer and Frank the Pug's dialogue, the Baltians were eliminated from the plot. Earth goes from being potentially destroyed in the crossfire between the two races into being possibly destroyed by the Arquillians themselves to prevent the Bugs from getting the galaxy.[2] These changes to the plot were carried out when only two weeks remained in the film's post-production, but the film's novelization still contains the Baltians.[5]

Design and visual effects

Production designer Bo Welch designed the MIB headquarters with a 1960s tone in mind, because that was when their organization is formed. He cited influences from Finnish architect Eero Saarinen, who designed a terminal at John F. Kennedy International Airport. As the arrival point of aliens on Earth, Welch felt the headquarters had to resemble an airport.[2]

Rick Baker was approached to provide the prostethic and animatronic aliens, many of whom would have more otherworldly designs instead of looking humanoid. For example, the reveal of Gentle Rosenberg's Arquillian nature went from a man with a light under his neck's skin to a small alien hidden inside a human head. Baker would describe Men in Black as the most complex production in his career, "requiring more sketches than all my previous movies together".[4] Baker had to have approval from both Sonnenfeld and Spielberg: "It was like, 'Steven likes the head on this one and Barry really likes the body on this one, so why don't you do a mix and match?' And I'd say, because it wouldn't make any sense." Sonnenfeld also changed a lot of the film's aesthetic during pre-production: "I started out saying aliens shouldn't be what humans perceive them to be. Why do they need eyes? So Rick did these great designs, and I'd say, 'That's great — but how do we know where he's looking?' I ended up where everyone else did, only I took three months."[6] The maquettes built by Baker's team would later be digitized by Industrial Light & Magic, who was responsible for the visual effects and computer-generated imagery, for more mobile digital versions of the aliens.[4]

Music

Two different soundtracks for the film were released in the U.S.: a score soundtrack featuring music composed by Danny Elfman and an album of songs used in and inspired by the film, featuring Will Smith's original song "Men in Black" based on the film's plot. In the UK, only the album was released.[citation needed]

Elfman's music was called "rousing" by the Los Angeles Times.[7] Variety called the film a technical marvel, giving special credit to "Elfman's always lively score."[8] Elfman was nominated for Best Original Musical or Comedy Score at the 70th Academy Awards for his score.[9]

Elvis Presley's cover of "Promised Land" is featured in the scene where the MIB's car runs on the ceiling of Queens–Midtown Tunnel.[10]

Release

Marketing

In advance of the film's theatrical release, its marketing campaign included more than 30 licensees.[11] Galoob was the first to license, in which they released various action figures of the film's characters and aliens.[12] Ray-Ban also partnered the film with a $5–10 million television campaign.[13] Other promotional items included Hamilton Watches[14] and Procter & Gamble's Head & Shoulders with the tagline "Keeping the Men in Black in black".[15]

An official comic adaptation was released by Marvel Comics. The film also received a third-person shooter Men in Black game developed by Gigawatt Studios and published by Gremlin Interactive, which was released to lackluster reviews in October 1997 for the PC and the following year for the PlayStation. Also, a very rare promotional PlayStation video game system was released in 1997 with the Men in Black logo on the CD lid. Three months after the film's release, an animated series based on Men in Black, produced by Columbia TriStar Television alongside Adelaide Productions and Amblin Television, began airing on The WB's Kids' WB programming block, and also inspired several games. A Men in Black role-playing game was also released in 1997 by West End Games.

Home media

Men in Black was first released on videocassette in standard and widescreen formats on November 25, 1997. Its home video release was attached to a rebate offer on a pair of Ray-Ban Predator-model sunglasses.[16] The film was re-released in a collector's series on videocassette and DVD on September 5, 2000, with the DVD containing several bonus features including an interactive editing workshop for three different scenes from the film, extended storyboards, conceptual art, and a visual commentary track with Tommy Lee Jones and director Barry Sonnenfeld; an alternate two-disc version was also released that had a fullscreen version on the first disc. The Deluxe Edition was also released on DVD in 2002.[17] A Blu-ray edition was released on June 17, 2008.[18] The entire Men in Black trilogy was released on 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray on December 5, 2017, in conjunction with the film's 20th anniversary.[19]

Reception

Box office

Men in Black grossed $250.6 million in the United States and Canada, and $338.7 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $589.3 million.[1] The film grossed a record $10.7 million in its opening weekend in Germany, beating the record held by Independence Day.[20]

Despite its grosses, writer Ed Solomon has said that Sony claims the film has never turned a profit, which is attributed to Hollywood accounting.[21]

Critical response

On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, Men in Black holds an approval rating of 92% based on 89 reviews, and an average score of 7.50/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Thanks to a smart script, spectacular set pieces, and charismatic performances from its leads, Men in Black is an entirely satisfying summer blockbuster hit."[22] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 71 out of 100, based on 22 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[23] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[24]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four, praising the film as "a smart, funny and hip adventure film in a summer of car wrecks and explosions."[25] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three stars out of four, giving particular praise to the film's self-reflective humor and Rick Baker's alien creature designs.[26] Janet Maslin, reviewing for The New York Times, wrote the film "is actually a shade more deadpan and peculiar than such across-the-board marketing makes it sound. It's also extraordinarily ambitious, with all-star design and special-effects talent and a genuinely artful visual style. As with his Addams Family films and Get Shorty, which were more overtly funny than the sneakily subtle Men in Black, Mr. Sonnenfeld takes offbeat genre material and makes it boldly mainstream."[27]

Writing for Variety, Todd McCarthy acknowledged the film was "witty and sometimes surreal sci-fi comedy" in which he praised the visual effects, Baker's creature designs and Elfman's musical score. However, he felt the film "doesn't manage to sustain this level of inventiveness, delight and surprise throughout the remaining two-thirds of the picture."[28] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly graded the film a C+, writing "Men in Black celebrates the triumph of attitude over everything else – plausibility, passion, any sense that what we're watching actually matters. The aliens, for all their slimy visual zest, aren't particularly scary or funny (they aren't allowed to become characters), and so the joke of watching Smith and Jones crack wise in their faces quickly wears thin."[29] John Hartl of The Seattle Times, claimed the film "is moderately amusing, well-constructed and mercifully short, but it fails to deliver on the zaniness of its first half." While he was complimentary of the film's first half, he concluded "somewhere around the midpoint they run out of energy and invention. Even the aliens, once they stop their shape-shifting ways and settle down to appear as themselves, begin to look familiar."[30]

Accolades

Men in Black won the Academy Award for Best Makeup, and was also nominated for Best Original Score and Best Art Direction. It was also nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy.[31]

| Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Art Direction | Bo Welch and Cheryl Carasik | Nominated |

| Best Makeup | Rick Baker and David LeRoy Anderson | Won | |

| Best Original Musical or Comedy Score | Danny Elfman | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Comedy or Musical | Nominated | |

| BAFTA Awards | Best Special Effects | Nominated | |

| Saturn Awards[32] | Best Science Fiction Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Barry Sonnenfeld | Nominated | |

| Best Writing | Ed Solomon | Nominated | |

| Best Actor | Will Smith | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Vincent D'Onofrio | Won | |

| Best Music | Danny Elfman | Won | |

| Best Make-Up | Nominated | ||

| Best Special Effects | Nominated |

On Empire magazine's list of the 500 Greatest Movies of All Time, "Men in Black" placed 409th.[33] Following the film's release, Ray-Ban stated sales of their Predator 2 sunglasses (worn by the organization to deflect neuralyzers) tripled to $5 million.[34]

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Agent J & Agent K - Nominated Heroes

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Men in Black" - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "You know the difference between you and me? I make this look good." - Nominated

- AFI's 10 Top 10 - Nominated Science Fiction Film

Sequels and spin-off

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Men in Black (1997)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i David Hughes (2003). Comic Book Movies. London: Virgin Books. pp. 123–129. ISBN 0-7535-0767-6.

- ^ "Summer Movie Preview". Entertainment Weekly. May 16, 1997. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Metamorphosis of 'Men in Black'", Men in Black Blu-ray

- ^ Donnelly, Billy (May 25, 2012). "Things Get A Bit Heated Between The Infamous Billy The Kidd And Director Barry Sonnenfeld When They Talk MEN IN BLACK 3". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ Steve Daly (July 18, 1997). "Men in Black: How'd they do that?". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (July 1, 1997). "The Outer Limits of Fun". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

...its charm is in its attitude and premise (and Danny Elfman's rousing score)...

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (June 29, 1997). "Reviews: Men in Black". Variety. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

Technically, the film is a marvel... In addition to the many effects hands, special credit should go to Bo Welch's constantly inventive production design, Don Peterman's ultra-smooth lensing and Danny Elfman's always lively score.

- ^ "THE 70TH ACADEMY AWARDS 1998". Oscars.org. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. n.d. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

MEN IN BLACK 3 NOMINATIONS, 1 WIN Art Direction - Art Direction: Bo Welch; Set Decoration: Cheryl Carasik – Music (Original Musical or Comedy Score) - Danny Elfman – * Makeup - Rick Baker, David LeRoy Anderson

- ^ Barry Sonnenfeld, Tommy Lee Jones. Visual Commentary. Men in Black.

- ^ Kirchdoerffer, Ed (June 1, 1997). "Special Report: Licensing International '97: Men in Black dressed FOR success". Kidscreen. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Taubeneck, Anna (May 11, 1997). "The Toys Of Summer". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Jensen, Jim (April 14, 1997). "High Hopes For 'Men in Black,' And Ray-Bans: Tie-In Marketers Key to Summer Films". AdAge. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ "What watch does Will Smith wear? - Almost On Time". March 15, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ Dignam, Conor (August 14, 1997). "ANALYSIS: Why marketers missed out on Men in Black ties". Campaign. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Arnold, Thomas (October 9, 1997). "The Art of The Tie-In". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ "Columbia TriStar Home Video: Men In Black Special Editions" (Press release). Internet Wire. July 26, 2000. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ "Men in Black DVD Release Date". DVDs Release Dates. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "Men in Black Trilogy 20th Anniversary 4K Blu-ray Collection". Blu-ray.com. September 26, 2017. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ "'Pie' flies high in Germany". Variety. October 15, 2001. p. 9.

- ^ Butler, Tom (December 31, 2020). "1997 hit 'Men in Black' is still yet to make a profit says screenwriter". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "Men in Black". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ "Men in Black Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ "Men in Black". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on August 9, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (July 4, 1997). "'Men In' Black' A Clever Romp". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 1, 1997). "Men in Black Movie Review & Film Summary (1997)". Ebert Digital LLC. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (July 1, 1997). "Oh, Aliens: Business As Usual". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (June 29, 1997). "Men in Black". Variety. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (July 11, 1997). "Men in Black". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Hartl, John (July 1, 1997). "'Men in Black': Sci-Fi Zaniness That Finally Crash-Lands". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ "Men in Black (1997) – Awards and Nominations". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on January 18, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ "Past Saturn Award Recipients". www.saturnawards.org. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "Empire's 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire Magazine. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ Jane Tallim (2002). "And Now a Word From Our Sponsor... Spend Another Day". Media Awareness Network. Archived from the original on August 19, 2008. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

External links

- Men in Black at IMDb

- Men in Black at AllMovie

- 1997 films

- Men in Black (franchise)

- 1990s English-language films

- 1997 action films

- 1990s buddy cop films

- 1997 comedy films

- 1997 science fiction films

- 1990s science fiction action films

- 1990s science fiction comedy films

- 1997 action comedy films

- American films

- American action comedy films

- American buddy cop films

- American science fiction action films

- American science fiction comedy films

- African-American action films

- African-American comedy films

- Amblin Entertainment films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Fictional government investigations of the paranormal

- Fictional-language films

- Flying cars in fiction

- Films about extraterrestrial life

- Films about insects

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films based on American comics

- Films directed by Barry Sonnenfeld

- Films with screenplays by Ed Solomon

- Films scored by Danny Elfman

- Films set in 1997

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in New Jersey

- Films shot in New York City

- Films that won the Academy Award for Best Makeup

- Films produced by Walter F. Parkes