Weng Chun: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

===Origins=== |

===Origins=== |

||

Both martial arts have lineages that attribute the creator to be Shaolin Monk [[Chi Sim]]<ref>Leung, Ting (2000). Roots and Branches of Wing Tsun, Second edition (January 1, 2000). Leung Ting Co ,Hong Kong. ISBN 9627284238, pg. 53, 90-99</ref><ref>Chu, Robert; Ritchie, Rene; Wu, Y. (2015). The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Tradition. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90-99</ref> |

Both martial arts have lineages that attribute the creator to be Shaolin Monk [[Chi Sim]].<ref>Leung, Ting (2000). Roots and Branches of Wing Tsun, Second edition (January 1, 2000). Leung Ting Co ,Hong Kong. ISBN 9627284238, pg. 53, 90-99</ref><ref>Chu, Robert; Ritchie, Rene; Wu, Y. (2015). The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Tradition. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90-99</ref> |

||

Sometimes the Weng Chun is also referred to as '''Chi Sim Wing Chun''' or '''Siu Lam Wing Chun''' by martial arts scholars.<ref>Robert Chu, Rene Ritchi, Y. Wu: Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90</ref>{{additional citations needed}} Here one refers to the legend of the Buddhist monk Chi Sim from the Siu Lam temple (better known under the transfer of the characters 少林 in the Mandarin pronunciation as "Shaolin"), who is considered to be an important forefather of several Kung Fu styles. These include Weng Chun (aka "Jee Shim Wing Chun"), Hung Kuen and Wing Chun.<ref>Robert Chu, Rene Ritchi, Y. Wu: Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90</ref>{{additional citations needed}} |

Sometimes the Weng Chun is also referred to as '''Chi Sim Wing Chun''' or '''Siu Lam Wing Chun''' by martial arts scholars.<ref>Robert Chu, Rene Ritchi, Y. Wu: Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90</ref>{{additional citations needed}} Here one refers to the legend of the Buddhist monk Chi Sim from the Siu Lam temple (better known under the transfer of the characters 少林 in the Mandarin pronunciation as "Shaolin"), who is considered to be an important forefather of several Kung Fu styles. These include Weng Chun (aka "Jee Shim Wing Chun"), Hung Kuen and Wing Chun.<ref>Robert Chu, Rene Ritchi, Y. Wu: Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90</ref>{{additional citations needed}} |

||

Revision as of 13:32, 12 November 2021

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

This article is missing information about Technical similiarities and differences of Weng Chun and Wing Chun?. (November 2021) |

Grand Master Andreas Hoffmann and Master Haydar Yilmaz demonstrating Chi Sao in action | |

| Also known as | Chi Sim Wing Chun, Siu Lam Wing Chun[1] |

|---|---|

| Focus | Self-defense |

| Creator | Allegedly Chi Sim, conceived at Southern Shaolin Temple.[2][3] |

| Parenthood | Ming-era Nanquan |

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese martial arts (Wushu) |

|---|

|

Weng Chun Kung Fu (Chinese: 永春; lit. 'eternal spring') is a Southern-style Chinese Martial Art.[4]

Weng Chun is considered a "soft" style martial art in that it utilizes the energy of the opponent to break structure rather than trying to match their energy. The main focus is on combining physical fitness with the health of both the body and mind. This is achieved through a combination of hard physical training and a deep underlying philosophy of understanding one's body movements and how and why they are employed. The ultimate goal in Weng Chun is complete mastery of both the body and the mind.[5]

History

There are many interpretations of the history of Weng Chun Kung Fu. The chronological history according to Grandmaster Andreas Hoffmann is detailed on the main Weng Chun website.[6] Other accounts have been documented by others including an extensive history of Weng Chun by Benny Meng and Jeremy Roadruck from the museum.[7][8]

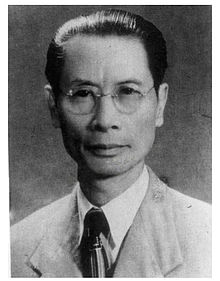

According to the oral tradition, the origins of Weng Chun Kung Fu lie in the Shaolin temples in southern China.[9] The most well-documented and historically important modern grandmaster of Weng Chun is identified as Chu Chung Man.[10][11][12] He was born in Foshan at the beginning of the 20th century and studied with teachers of various Kung Fu styles for many years, including Weng Chun Kung Fu.[13] Chu Chung Man was also a good friend of Yip Man.[14] Chu Chung Man worked as a practicing doctor in Macau during the Second World War, and from 1953 as a doctor in a hospital in Hong Kong. He is considered a fifth generation student of Weng Chun Kung Fu after the alleged founder Chi Sim.[15]

When Chu Chung Man moved to Hong Kong in 1953, he met other Weng Chun Kung Fu grandmasters who taught a comparatively large number of students, including Grand Masters Tang Yik and Wai Yan. Wai Yan was the managing director of a poultry wholesaler in Kowloon and temporarily converted the department store into a training hall in which the Weng Chun grandmasters met for a long time to exchange ideas.[16][17] The name of the wholesaler Dai Tak Lan was also the name for the training hall, which was to acquire a certain significance for Weng Chun Kung Fu in the post-war period. [18]

The grandmasters themselves and their descendants had and still have various students who did not come from China.[19] They made Weng Chun Kung Fu known outside of China and founded various martial arts schools and associations. As with Wing Chun Kung Fu, aspects of trademark law led to different names for the schools. In addition, the grandmasters of the Dai Tak Lan Center always taught slightly different variants of Weng Chun Kung Fu as part of their family tradition.

Nevertheless, all of the schools mentioned refer to the Dai Tak Lan Center and the families of the grandmasters, especially Wai Yan, Tang Yik and Chu Chung Man.

Present

Weng Chun in its present form is being preserved by many, including Andreas Hoffman,[20] the successor of the art following late Grand Master Wai Yan.

Philosophy

The philosophy of Weng Chun Kung Fu, like many martial arts relates to a way of life that goes much deeper than just fighting. Indeed, the traditional philosophy of kung fu relates to how to live one's life, rather than discovering truth in reality.[21]

Weng Chun Kung Fu reflects this path in five levels of wisdom stretching for the basic understanding of physical moves such as how to throw a punch all the way to complete mastery of the body and mind, where the philosophy of kung fu extends to all aspects of the practitioner's life.[22]

The basic level is known as Ying, which teaches basic forms and shapes. Ying can be considered the study of "what" techniques there are in combat, such as how to punch, or kick. The student achieves a deeper understanding of how to make these moves at the next level, known as Yi, where the principles used in Weng Chun are learned. Yi teaches the bridges and techniques employed in combat, focusing on the 18 Kiu Sao concepts. The third level, Lei then considers the shapes and forms employed in Ying and Yi and internalises these into an instinctive system, helped by mastering the forms through repetition. The student's skills developed in fighting can then be extended into other aspects of their lives, where discipline, self-control and other qualities can be employed into a philosophy of living the kung fu life. The next level is known as Faat (in Buddhism Dharma) which explores the methods, or ways of understanding reality. In Shaolin Weng Chun reality is expressed in space/time (heaven), energy (human) and gravity/identity (earth).

Finally Seut, meaning skill and showmanship relates to the expression of Weng Chun in our everyday lives where discipline, respect and the correct interaction with others is realized. The practitioner has at this point achieved mastery and all their actions are reflected in the kung fu life.[23]

Understanding distances and vectors

Three main distances are recognised in Weng Chun: Heaven (far), Earth (near, or close) and Man (contact). Each distance involves employing different strategies. Heaven and earth distances require the practitioner to bridge the gap between opponents whereby circling is employed as a basis for movements such as forwards/backwards (tan/to), or tiu (to sink) for example. There are 18 bridges in Kiu Sao (bridging arm) to achieve this and six vectors including forwards/backwards, left/right and up/down, all used in combination.

Principles

There are two sets of principles employed in Weng Chun: The seven principles developed from the pole form (often referred to as the 6 1/2 principles) and the more advanced 18 principles employed in Kui Sao (bridging hands).

The 6 1/2 principles

The basic seven principles employed in Weng Chun Kung Fu are described by Grandmaster Andreas Hoffman in Budo International magazine (PDF) page 20., although they are often referred to as the six and half principles. These stem from the Luk Dim Boon Kwun long pole form, which is practiced in both Weng Chun and Wing Chun. Grandmaster Andreas Hoffmann has developed a further form known as Luk Dim Boon Kuen to teach these principles without need for the long pole. Together they form the basis of Weng Chun and include:

- Tai (to raise). This principle deploys any upward movement and is primarily used to destroy the balance of the attacker.

- Lan (to lock, or control). Lan is used to close down the attacker and enables the practitioner to counterattack.

- Dim (point shock). Dim is used, for example, when striking; it focuses the attack on a point in order to shock the attacker.

- Kit (tear and open up). Effectively a two-part principle, kit involves closing down an attack and creating an opening in its place.

- Got (half circle downwards). Got is used, for example, to stop or block an opponent's strike

- Wun (circle). Circling is a central principle in Weng Chun and encompasses a ranging of moves that employ a circling movement

- Lau (flow). The last principle of flowing is considered a half principle in Weng Chun, but is perhaps the most important as when combined with the other principles it brings Weng Chun to life.

The 18 principles in Kui Sao

Kui Sao enables the fighter to adopt a position, or perfect their timing to have the greatest effect with the least use of force, which enables them to easily deal with their opponent. The more advanced 18 bridging (kiu) principles as described by Grandmaster Andreas Hoffman in Budo International, issue 55 are taught in nine matching (yin & yang) pairs, which include:

- Tiu - But: Sideways movement of the arms or legs in a windscreen-wiper motion, used to control the attacker

- Da - Pun: Strike and fold

- Jaau - Lai: Push and pull

- See - Che: Shock by puling and striking

- Kam - Na: Catch and control by locking

- Fung Bai: Trap, or stop and build a barrier

- Bik - Hip: Cornering and overrunning the opponent

- Tun - Tuo: Swallow and spit by absorbing and striking

- Bok - Saat: Guide and surf opponent then attack

A short video demonstrating the 18 Kui Sao can be seen here: GM Andreas Hoffman explaining Kui Sao

Weng Chun Forms

All Weng Chun forms consist of standardized movements, with which the basic principles of Weng Chun are internalized. Regular training internalizes the movements into the mind and body, so that they can be called up spontaneously in self-defense. The forms offer the advantage that one can train at any time and any place, either alone or in groups.

Weng chun forms include:

Weng Chun Kuen (Perpetual Spring Fist) The Weng Chun (Sap Yat) Kuen is the core set of Weng Chun, a basic practice form consisting of 11 sections, which is applied in Chi Sao. In fact, it could also be termed more of a "theory" than a "form"—a set of methods for optimizing the free use of the body to win over a strong attacker introducing the 18 Kiu Sao of Weng Chun.

Fa Kuen (Flower Fist) The flower is the symbol of the Sim (Chan/Zen) philosophy . The body work of Weng Chun Kuen and Fa Kuen were made famous by Grandmaster Chu Chung Man. This set teaches how to use the entire body for both long and short distance fighting. In the Weng Chun family there are different versions of Fa Kuen: short versions, long versions and even different sets with the name Fa Kuen.

Luk Dim Boon Kuen (Six and a Half Point principle form) This form teaches the feeling and understanding of the 6½ principles and concepts as originally taught in the Six and a Half Point Pole form (Luk Dim Boon Kwun), as detailed below. Like many of the concepts used in Weng Chun, this develops principles originally used with weapons and applies them to the unarmed practitioner.

Saam Pai Fat (Three Bows to Buddha) According to the Lo family, Saam Pai Fat is the advanced Weng Chun set of Sun Gam (Dai Fa Min Gam) of the Red Boat Opera. Like its matching set, Weng Chun Kuen, Saam Pai Fat consists of eleven sections. Its focus is to expand the ability of the Weng Chun Kuen practitioner to cover all of space and time through the concept of bowing to Heaven, Earth, and Man. A video clip of GM Andreas Hoffman demonstrating Saam Pai Fat can be seen here.

Jong Kuen (Structure Fist) Jong Kuen (also known as Siong Kung Jong Kuen because in the final Weng Chun teaching it melds internal and external power), combines fast, agile steps in all directions with whole body movement. The set includes all concepts and principles from the long pole, wooden dummy, etc. In appearance, this last, traditional Weng Chun set looks similar to a combination of Taijiquan, Xingyiquan, and Baguazhang.

Ng Jong Hei Gung (Five Posture Qi Gong) Ng Jong Hei Gong teaches five postures for the cultivation of Hei (Qi), and the development of strong, Weng Chun Kuen body structure. It opens the small and the Large Heaven Qi circles and balances the Qi of the inner organs.

Muk Yan Jong (Wooden Dummy) The Muk Yan Jong contains three sets: Tien Pun (Heaven), Dei Pun (Earth), and Yan Pun (Human). In them are contained the fighting methods of the Muk Yan Hong, the Wooden Dummy Hall of the Southern Shaolin Temple. The Wooden Dummy is not used just to strengthen forearms or shins, but with the sensitivity found in Chi Sao.

Luk Dim Boon Kwun (Six and a Half Point Pole) The pole is the heart of Weng Chun Kuen. With it comes the feeling and understanding of the 6½ principles and concepts used in all types of fighting. The set begins with Hei Gung that teaches to control space through "spring" footwork, and continues on to challenge practitioners to make use of their whole bodies.

Kwun Jong (Pole Dummy) The long range wooden dummy was, in times past, the secret of Weng Chun Kuen. It is the fourth and final dummy from the Muk Yan Hong (Wooden Dummy Hall) of the Southern Shaolin Temple. It teaches to close the gap over and over again.

Fu Mo Siong Dao (Father & Mother Double Knives) The Father & Mother Double Knives gives a practical fighting system with sharp weapons and introduces the concept of Yum Yeung (Yin and Yang). The transfer of pole principles to sharp, double-handed weapons also increases fighting spirit.

Difference between Weng Chun and Wing Chun

Weng Chun is often confused with another Southern Kung Fu style Wing Chun.[according to whom?] Weng Chun and Wing Chun are two different Kung Fu styles, and is assumed so by martial arts scholars [24][25][page needed][26][27][page needed], including Ip Man.[28][29] Weng Chun is considered a sister martial art to Wing Chun,[30][additional citation(s) needed] as both styles contains notable similarities and differences:

Name

In Cantonese, the characters 永 (wing5 in the Jyutping system) and 咏 (wing6 in the Jyutping system) are pronounced very similarly. For people who do not speak Cantonese, the slight difference in pronunciation is barely noticeable. The character 咏 is assigned to the Kung Fu style Wing Chun (咏 春), which roughly means "spring song". In standard Chinese, the identical pronunciation Yǒng (yong3 in the Pinyin system) is used for the characters 永 and 咏; so they are homophones. [need quotation to verify]

Origins

Both martial arts have lineages that attribute the creator to be Shaolin Monk Chi Sim.[31][32]

Sometimes the Weng Chun is also referred to as Chi Sim Wing Chun or Siu Lam Wing Chun by martial arts scholars.[33][additional citation(s) needed] Here one refers to the legend of the Buddhist monk Chi Sim from the Siu Lam temple (better known under the transfer of the characters 少林 in the Mandarin pronunciation as "Shaolin"), who is considered to be an important forefather of several Kung Fu styles. These include Weng Chun (aka "Jee Shim Wing Chun"), Hung Kuen and Wing Chun.[34][additional citation(s) needed]

One particular difference between the two is that while Wing Chun mainly perpetuated amongst Red Boat Opera Company, Weng Chun perpetuated outside of it.

Technical differences

Weng Chun bears more similarity to another Southern Chinese Kung Fu style Hung Gar, rather than Wing Chun.[35][additional citation(s) needed]

References

- ^ Robert Chu, Rene Ritchi, Y. Wu: Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90

- ^ Leung, Ting (2000). Roots and Branches of Wing Tsun, Second edition (January 1, 2000). Leung Ting Co ,Hong Kong. ISBN 9627284238, pg. 53, 90-99

- ^ Chu, Robert; Ritchie, Rene; Wu, Y. (2015). The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Tradition. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90-99

- ^ Werner Lind: Das Lexikon der Kampfkünste. Sportverlag Berlin, 2001, ISBN 3-328-00898-5, page. 530

- ^ admin (2014-02-08). "Are "Wing Chun" and "Weng Chun" closely related sister arts?". Sifu Sergio. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-10-23. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Chu, Ritchie & Wu 2015, p. 90

- ^ Chu, Robert; Ritchie, Rene; Wu, Y. (2015). The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Tradition. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90-99

- ^ http://web.archive.org/web/20120524154506/http://naamkyun.com:80/2012/03/interview-with-wing-chun-grandmaster-yip-man/

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20160408020528/https://www.heritagemuseum.gov.hk/documents/2199315/2199679/first_ICH_inventory_e.pdf

- ^ Leung Ting: Roots of Wing Tsun. Leung's Publications, Hongkong 2000, page 371

- ^ Leung Ting: Roots of Wing Tsun. Leung's Publications, Hongkong 2000, pages 47–48

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20200123213320/https://www.shaolin-wengchun.com/2008EN/history.html

- ^ Leung Ting: Roots of Wing Tsun. Leung's Publications, Hongkong 2000, p. 371

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20200123213320/https://www.shaolin-wengchun.com/2008EN/history.html

- ^ Chu, Robert; Ritchie, Rene; Wu, Y. (2015). The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Tradition. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90-99

- ^ Chu, Ritchie & Wu 2015, p. 90

- ^ "Andreas Hoffman Chi Sim Weng Chun Kung Fu DVDs". www.everythingwingchun.com. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ Ni, Peimin (8 December 2010). "Kung Fu for Philosophers". nytimes.com.

- ^ in 2001, <img src="https://www wingchunillustrated com/wp-content/uploads/gravatar/kleber_profile_pic jpg" class="photo" width="80" /> Kleber BattagliaInstructor at Practical Wing Chun Shanghai ClubKleber started training WSLVT; Since 2009; present, he has studied Practical Wing Chun under Sifu Wan Kam Leung At; Shanghai, he is teaching Practical Wing Chun in (2017-11-24). "Sunny So: The Four Elements of Weng Chun » Wing Chun Illustrated". Wing Chun Illustrated. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Adapted from an article authored by Benny Meng in" Kung Fu & Tai Chi mag", February 2005

- ^ Frank Paetzold: "Das Wing Tsun Buch", page. 41, Books on Demand GmbH (2005)

- ^ Robert Hill, "World Of Martial Arts!: The History of Martial Arts", ISBN-13: 9781257721115

- ^ https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2015/07/23/from-the-archives-global-capitalism-the-traditional-martial-arts-and-chinas-new-regionalism/

- ^ Benjamin N. Judkins, Jon Nielson: "The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts", State University of New York (2015) ISBN: 1438456948

- ^ Leung Ting: Roots of Wing Tsun. Leung's Publications, Hongkong 2000, page. 48

- ^ http://web.archive.org/web/20120524154506/http://naamkyun.com:80/2012/03/interview-with-wing-chun-grandmaster-yip-man/

- ^ https://sifusergio.com/wing-chun-weng-chun-closely-related-sister-arts/

- ^ Leung, Ting (2000). Roots and Branches of Wing Tsun, Second edition (January 1, 2000). Leung Ting Co ,Hong Kong. ISBN 9627284238, pg. 53, 90-99

- ^ Chu, Robert; Ritchie, Rene; Wu, Y. (2015). The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Tradition. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90-99

- ^ Robert Chu, Rene Ritchi, Y. Wu: Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90

- ^ Robert Chu, Rene Ritchi, Y. Wu: Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90

- ^ Robert Chu, Rene Ritchi, Y. Wu: Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462917532, pg.90