Ageing: Difference between revisions

m →Cultural variations: indian POV |

|||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

Traditional Chinese culture use different ageing method, called ''Xusui'' (虛歲) with respect to common ageing which called ''Zhousui'' (周歲). In the ''Xusui'' method, people are born at age 1, not age 0. See also [[East Asian age reckoning]] for more information. |

Traditional Chinese culture use different ageing method, called ''Xusui'' (虛歲) with respect to common ageing which called ''Zhousui'' (周歲). In the ''Xusui'' method, people are born at age 1, not age 0. See also [[East Asian age reckoning]] for more information. |

||

Traditional medicine in India claims that [pure gold] has several therapeutic qualities: when consumed regularly, gold is good for circulation of the blood and enhancement of the mind and lifting the spirit: gold applied to skin helps combat ageing. |

Traditional medicine in India claims that [pure gold] has several therapeutic qualities: when consumed regularly, gold is good for circulation of the blood and enhancement of the mind and lifting the spirit: gold applied to skin helps combat ageing.<ref>url=http://jadtar.blogspot.com</ref> |

||

==Effects== |

==Effects== |

||

Revision as of 19:54, 6 February 2007

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. |

Ageing or aging is the process of becoming older. This traditional definition was recently challenged in the new "Handbook of the Biology of Aging" (Academic Press, 2006), where ageing was specifically defined as the process of system's deterioration with time, thus allowing for existence of non-ageing systems (when "old is as good as new"), and anti-ageing interventions (when accumulated damage is repaired). This article focuses on the social, cognitive, cultural, and economic effects of ageing. The biology of ageing is treated in detail in senescence. Ageing is an important part of all human societies reflecting the biological changes that occur, but also reflecting cultural and societal conventions. Age is usually measured in full years (except for young children, where this downward rounding would be too crude) and a person's birthday is often an important event.

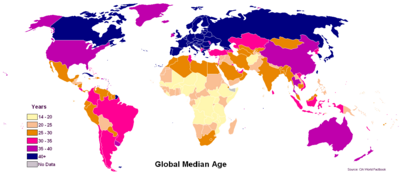

The issues of an ageing population in which the average age of a society is an increasingly important issue in many nations of the world. The societal effects of age are great. Young people tend to commit most crimes, they are more likely to push for political and social change, to develop and adopt new technologies, and to need education. Older people have different requirements from society and government as opposed to young people, and frequently differing values as well. Older people are also far more likely to vote, and in many countries the young are forbidden from voting, and thus the aged have comparatively more political influence.

Senescence

In biology, senescence is the state or process of ageing. Cellular senescence is a phenomenon where isolated cells demonstrate a limited ability to divide in culture (the "Hayflick Limit," discovered by Leonard Hayflick in 1965), while Organismal senescence is the ageing of organisms.

Ageing is believed to have evolved because of the increasingly smaller probability of an organism still being alive at older age, due to predation and accidents, both of which may be random and age-invariant. It is thought that strategies which result in a higher reproductive rate at a young age, but shorter overall lifespan, result in a higher lifetime reproductive success and are therefore favoured by natural selection. Essentially, aging is therefore the result of investing resources in reproduction, rather than maintenance of the body (the "Disposable Soma" theory).

Organismal ageing is generally characterized by the declining ability to respond to stress, increasing homeostatic imbalance and increased risk of disease. Because of this, death is the ultimate consequence of ageing. Not all organisms age, presumably due to different selective pressures during evolution. Organisms that are suspected not to age include certain fish (e.g., Sturgeon), plants, and hydra.

Some researchers are treating ageing as a "disease" in gerontology (specifically biogerontologists). That is, as genes that have an effect on ageing are discovered, ageing is increasingly being regarded in a similar fashion to other genetic conditions; potentially "treatable." As an example of genes known to affect the aging process, the sirtuin family of genes have been shown to have a significant effect on the lifespan of yeast and nematodes. Numerous other examples exist of genes that affect lifespan including RAS1 and RAS2 (yeast genes, although a human homologue exists). Overexpression of RAS2 increases lifespan in yeast substantially. Genes have also been located in which occur more frequently in people who reach ages of 100+, providing a correlative, if not causative link to aging.

In addition to genetic ties to lifespan, diet has been shown to substantially affect lifespan in many animals. Specifically, caloric restriction (that is, restricting calories to 30-50% less than an ad libitum animal would consume, while still maintaining proper nutrient intake), has been shown to increase lifespan in mice up to 50%. Caloric restriction works on many other species beyond mice (including species as diverse as yeast and Drosophila), and appears (though the data is not conclusive) to increase lifespan in primates according to a study done on Rhesus monkeys at the National Institute of Health (US).

Drug companies are currently searching for ways to mimic the lifespan-extending affects of caloric restriction without having to severly reduce food consumption, and with respect to cellular senescence, it has been shown that individual cells can be immortalized by the introduction of an additional gene for telomerase.

Dividing the lifespan

A human life is often divided into various ages. Because biological changes are slow moving and vary from person to person arbitrary dates are usually set to mark periods of human life. In some cultures the divisions given below are quite varied.

In the USA, adulthood legally begins at the age of eighteen or nineteen, while old age is considered to begin at the age of legal retirement (approximately 65).

- Pre-Conception - Ovum, Spermatozoon, Pre-existence

- Conception - Fertilisation

- Pre-birth conception - 9 months

- Infancy birth - 2

- Childhood 2 - 12

- Adolescence 13 - 19

- Early Adulthood 20 - 39

- Middle Adulthood 40 - 64

- Late Adulthood 65+

- Death

- Post-Death - Afterlife, Ghost, Cryogenics, Decomposition

Ages can also be divided by decade:

- Vicenarian: someone between 20 and 29 years of age

- Tricenarian: someone between 30 and 39 years of age

- Quadragenarian: someone between 40 and 49 years of age

- Quinquagenarian: someone between 50 and 59 years of age

- Sexagenarian: someone between 60 and 69 years of age

- Septuagenarian: someone between 70 and 79 years of age

- Octogenarian: someone between 80 and 89 years of age

- Nonagenarian: someone between 90 and 99 years of age

- Centenarian: someone between 100 and 109 years of age

- Supercentenarian: someone over 110 years of age

See also Seven ages of man for an older system of dividing the human life.

In some cultures (for example Serbian and Russian) there are two ways to express age: by counting years with or without including current year. For example it could be said about the same person that he is twenty years old or that he is in twenty-first year of his life.

Society

Legal

There are variations in many countries as to what age a person legally becomes an adult.

In the United States there are issues such as voting age, drinking age, age of consent, age of majority, age of criminal responsibility, marriageable age, age where one can hold public office, and mandatory retirement age. Admission to a movie for instance, may depend on age according to a motion picture rating system.

Similarly in the United States in jurisprudence, the defence of infancy is a form of defence by which a defendant argues that, at the time a law was broken, they were not liable for their actions, and thus should not be held liable for a crime. Many courts recognize that defendants, which are considered to be juveniles, may avoid criminal prosecution on account of their age.

Economics and marketing

The economics of ageing are also of great import. Children and teenagers have little money of their own, but most of it is available for buying consumer goods. They also have considerable impact on how their parents spend money.

Young adults are an even more valuable cohort. They often have jobs with few responsibilities such as a mortgage or children. They do not yet have set buying habits and are more open to new products.

The young are thus the central target of marketers.[1] Television is programmed to attract the 15 to 35 years olds. Movies are also built around appealing to the young.

Cultural variations

Considerable numbers of cultures have less of a problem with age compared with what has been described above, and it is seen as an important status to reach stages in life, rather than defined numerical ages. Advanced age is given more respect and status.

Traditional Chinese culture use different ageing method, called Xusui (虛歲) with respect to common ageing which called Zhousui (周歲). In the Xusui method, people are born at age 1, not age 0. See also East Asian age reckoning for more information.

Traditional medicine in India claims that [pure gold] has several therapeutic qualities: when consumed regularly, gold is good for circulation of the blood and enhancement of the mind and lifting the spirit: gold applied to skin helps combat ageing.[2]

Effects

Cognitive

Steady decline in many cognitive processes are seen across the lifespan, starting in one's thirties. Research has focused in particular on memory and ageing, and has found decline in many types of memory with ageing, but not in semantic memory or general knowledge such as vocabulary definitions, which typically increases or remains steady.

Emotional

Given the physical and cognitive declines seen in ageing, a surprising finding is that emotional experience improves with age. Older adults are better at regulating their emotions and experience negative affect less frequently than younger adults and show a positivity effect in their attention and memory. The emotional improvements show up in longitudinal studies as well as in cross-sectional studies, and so cannot be entirely due to only the happier individuals surviving.

Successful ageing

The concept of "successful ageing", as Strawbridge et al. (2002), have pointed out, can be traced back to the 1950s, but was popularised in an article by Rowe and Kahn (1987). These authors believed that former research into ageing had exaggerated the extent to which health disabilities, such as diabetes or osteoporosis, could be attributed exclusively to age, and also criticised former research in gerontology for exaggerating the homogeneity of samples of elderly people. In a subsequent publication, Rowe and Kahn (1997) criticise earlier work for making what, to them, is an over-simplistic distinction between pathologic and non-pathologic ageing, and distinguish between "normal ageing" (marked by high risk of illness), and "successful ageing" (marked by low risk of disability and high cognitive and physical functioning). They define "successful ageing" more specifically as consisting of three components: 1. Low probability of disease or disability; 2. high cognitive and physical function capacity; 3. active engagement with life. Criticisms of Rowe and Kahn's work has been noted by Strawbridge et al. (2002), who note that more liberal definitions of "successful ageing" than those proposed by Rowe and Kahn result in greater percentages of elderly adults reaching successful ageing, and that self-reported successful ageing suggests a greater number of elderly people reach successful ageing than does an operational measure based on Rowe and Kahn's conceptualisations. Indeed, Strawbridge et al. (2002) note that the term "successful ageing", insofar as it implies competitiveness and that "normal ageing" is a failure, is itself problematic, and review alternative terms (such as "healthy ageing") that have been proposed.

Notes

- '^ Krulwich, Robert (2006). Does Age Quash Our Spirit of Adventure? NPRs "All Things Considered" (accessed August 22, 2006)

- ^ url=http://jadtar.blogspot.com

References

- Charles, S.T., Reynolds, C.A., & Gatz, M. (2001). Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 136-151.

- Mather, M., & Carstensen, L. L. (2005). Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9, 496-502. PDF

- Masoro E.J. & Austad S.N.. (eds.): Handbook of the Biology of Aging, Sixth Edition. Academic Press. San Diego, CA, USA, 2006. ISBN 0-12-088387-2

- Global Social Change Reports One report describes global trends in ageing.

- Rowe, J.D. & Kahn, R.L. (1987). Human ageing: Usual and successful. Science, 237, 143-149

- Rowe, J.D. & Kahn, R.L.(1997). Successful ageing. The Gerontologist, 37 (4) 433-40

- Strawbridge, W.J., Wallhagen, M.I. & Cohen, R.D. (2002). Successful ageing and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. The Gerontologist, 42, (6)

- Zacks, R.T., Hasher, L., & Li, K.Z.H. (2000). Human memory. In F.I.M. Craik & T.A. Salthouse (Eds.), The Handbook of Aging and Cognition (pp. 293-357). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

See also

- Aging DNA

- Aging and memory

- Aging Research Centre

- American Federation for Aging Research

- Brain aging

- Biological immortality

- Senescence

- Life expectancy

External links

- Aging Research Centre

- American Federation for Aging Research

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding ageing

- Ageing Simulation Video

- International Plan on Ageing of the UN, 2002, Madrid

- Mortality Patterns Suggest Lack of Senescence in Hydra, Martinez, 1998

- Is there a secret to preventing aging?

- Aging Information

- Theory of Aging Information

- Eye color can change as we age from WonderQuest