St. Charles Municipal Building: Difference between revisions

m →top: Task 30, removal of invalid parameter from Template:Infobox NRHP |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

| ⚫ | The building is the basis for the Rapture Lighthouse in the video game series ''[[BioShock]]''. Artist Dave Flamburis, who designed the Lighthouse, described the St. Charles Municipal Building as a "striking and amazing piece of Art Deco architecture." When he saw the building, "Like – wham! That was it. Everything settled around that core design." |

||

{{more citations needed|date=September 2019}} |

|||

<ref>{{cite web|url=https://bioshock.fandom.com/wiki/The_Lighthouse|title=The Lighthouse|publisher=BioShock Wiki}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | The building is the basis for the Rapture Lighthouse in the video game series ''[[BioShock]]''. Artist Dave Flamburis, who designed the Lighthouse, described the St. Charles Municipal Building as a "striking and amazing piece of Art Deco architecture." When he saw the building, "Like – wham! That was it. Everything settled around that core design." |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 19:42, 21 January 2022

St. Charles Municipal Building | |

| |

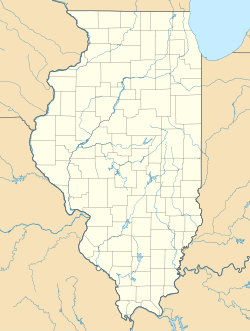

Location in Illinois | |

| Location | 2 East Main St. St. Charles, Illinois, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°54′50.46″N 88°18′46.37″W / 41.9140167°N 88.3128806°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1940 |

| Architect | R. Harold Zook and D. Coder Taylor |

| Architectural style | Art Deco or Moderne |

| NRHP reference No. | 91000087[1] |

| Added to NRHP | February 21, 1991 |

The St. Charles Municipal Building is a historic building and civic center in St. Charles, Illinois, United States. It was constructed in 1940 and donated to St. Charles, and has since served as its seat of local government. It has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1991.[1]

History

The office of R. Harold Zook was chosen to design the structure. Zook operated out of Chicago, working with his nephew D. Coder Taylor, whom he considered his protege. Coder Taylor began working for his uncle in 1935 and recalled that they took any work they could get. Taylor described his uncle as "a good salesman" describing how he got the commission for the St. Charles Municipal Building. He described it as "a big project for the Zook office" and that the office staff at that time was "Zook, Taylor, sometimes another draftsman, and a lady secretary."[2]

Zook made a preliminary drawing, a proposed elevation, and that was as far as he went. Coder Taylor recalled the client "wasn't too impressed by it." The initial design was of lannon stone. The client wanted something more modern and impressive. Coder Taylor took over the project and from that point on made every drawing on the project.[3]

"The name credited isn't always the person who is the most influential on the project", recalled Taylor. However it wasn't quite that simple, he said that he and his uncle's tables were three feet apart. "He saw what I was doing, so he would comment. If I wouldn't do it right, in his opinion, or he didn't like what I was doing, he would comment. We'd discuss it and the thing would come out. It was mine plus his input that perfected the design."[3]

Coder Taylor described that it was changed to a "much more Art Deco type of design than it was at the outset".[3]

Quoting the Architectural Record March 1941 issue: "This building was planned for an individual who then donated it to St. Charles at the time of its dedication."[4] Coder Taylor remembered his client, Col. E. J. Baker, "who was a millionaire as a result of inheriting quite a lot of money from Bet-a-million Gates." Taylor described that Col. Baker's niece Dellora and her husband Les Norris, who also shared in the inheritance, donated the land along the Fox River and Baker donated the building. He said that Baker wanted marble, Georgia marble because it is a hard marble and he'd had the St. Charles National Bank built, done of pink Georgia marble. In its design and construction, both Col. Baker and Coder Taylor wanted the building to last, to stand through time and to age gracefully. So Taylor went to Georgia to select the white Georgia marble and saw how to get the proper finish. "It was a rough finish, done with a hammer."[3]

Coder Taylor recalled working with Col. Baker:

Baker was quite determined, and this is the way he wanted to handle the building design. He didn't know anything about city halls. I'm not sure we knew a great deal about city halls either. But he didn't want to consult with the mayor or any of the people in the city offices. He wanted to build a building and donate it to them after it was completed. We had to do a little research, just what do you have in a city hall? What he wanted was the municipal offices in the building, but with a wing to the side for an industrial museum. That's what it was intended to be. However, it wasn't really industry, it was principally historical... He was very pleased with it, and very proud of it.[3]

"The village was delighted to receive it", but Coder Taylor recalled that Col. Baker did not allow city officials to be involved with the project: "He didn't care for the mayor, he didn't care for any of the councilmen, the staff didn't matter anyway, the city collector and all this. He didn't give them the opportunity to comment. We designed it without conferences with anybody, and we supervised the construction."[3]

The Municipal Building was described as "an unusual building in many respects" and is iconic of the City of St. Charles.

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991 in the category of Architecture/Engineering.[5]

Design

The building's design was inspired by the Art Deco movement, but its architectural style has been characterized as Moderne.[1][5][6] The National Register nomination characterizes it as Moderne rather than Art Deco due to the fact that it "is an example of the phase of design after 1930 in which buildings were drastically stripped of surface ornaments and windows were grouped in bands."[1]

Its exterior features white Georgia "Cherokee" marble and a base of black granite, with prominent motifs of "faceted surfaces, zigzags, chevron patterns, and octagon shapes".[1][6]

The Municipal Building has served continuously as the seat of local government in St. Charles since its dedication in 1940. In order to comply with the Americans With Disabilities Act, a new entry atrium was constructed in 1995 to provide the building with an elevator. The two-story structure connected the Municipal Building with the original 1892 City Building.[7]

The city has expanded its office spaces in the building over the years. The St. Charles History Museum which had been located in the building was moved to the historic McCornack Oil Co. Texaco gas station building in 2001.[8]

In popular culture

The building is the basis for the Rapture Lighthouse in the video game series BioShock. Artist Dave Flamburis, who designed the Lighthouse, described the St. Charles Municipal Building as a "striking and amazing piece of Art Deco architecture." When he saw the building, "Like – wham! That was it. Everything settled around that core design." [9]

References

- ^ a b c d e "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ^ "Letter from Coder Taylor". Illinois Digital Archives.

- ^ a b c d e f "Oral history of D. Coder Taylor". Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ "Architectural Record". Illinois Digital Archives.

- ^ a b Caryn Hannan (2008). Illinois Encyclopedia. State History Publications. p. 484.

- ^ a b "St. Charles Municipal Building". Enjoy Illinois.

- ^ "Municipal Center - St. Charles Historic Buildings". St. Charles Public Library.

- ^ "McCornack Oil Company - St. Charles Historic Buildings". St. Charles Public Library.

- ^ "The Lighthouse". BioShock Wiki.

External links

- St. Charles, Illinois

- National Register of Historic Places in Kane County, Illinois

- Buildings and structures in Kane County, Illinois

- City and town halls on the National Register of Historic Places in Illinois

- City and town halls in Illinois

- Moderne architecture in the United States

- Buildings and structures completed in 1940