Nedîm: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by Chulashton (talk) to last version by Uness232 |

Chulapi papi (talk | contribs) m i fixed it Tags: Reverted extraneous markup |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==Life== |

==Life== |

||

{{History of Turkish literature}} |

{{History of Turkish literature}} |

||

Nedim, whose real name was Ahmed (أحمد), was born in [[Constantinople]] sometime around the year 1681. His father, Mehmed Efendi, had served as a chief military judge (قاضسکر ''kazasker'') during the reign of the Ottoman [[sultan]] [[Ibrahim of the Ottoman Empire|Ibrahim I]]. At an early age, Nedim began his studies in a ''[[Madrassa|medrese]]'', where he learned both [[Arabic language|Arabic]] and [[Persian language|Persian]]. After completing his studies, he went on to work as a scholar of [[Sharia|Islamic law]]. |

Nedim, whose real name was Ahmed (أحمد), was born in [[Constantinople]] sometime around the year 1681. His father, Mehmed Efendi, had served as a chief military judge (قاضسکر ''kazasker'') during the reign of the Ottoman [[sultan]] [[Ibrahim of the Ottoman Empire|Ibrahim I]]. At an early age, Nedim began his studies in a ''[[Madrassa|medrese]]'', where he learned both [[Arabic language|Arabic]] and [[Persian language|Persian]]. After completing his studies, he went on to work as a scholar of [[Sharia|Islamic law]]. he aslo looks like he has a reeses on his head<ref></ref> |

||

In an attempt to gain recognition as a poet, Nedim wrote several ''[[Qasida|kasîde]]''s, or [[panegyric]] poems, dedicated to [[Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha|Ali Pasha]], the Ottoman [[Grand Vizier]] from 1713 to 1716; however, it was not until — again through ''kasîde''s — he managed to impress the subsequent Grand Vizier, [[Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha|Ibrahim Pasha]], that Nedim managed to gain a foothold in the [[Topkapı Palace|court of the sultan]]. Thereafter, Nedim became very close to the Grand Vizier, who effectively served as his sponsor under the Ottoman [[Patronage|patronage system]]. Ibrahim Pasha's viziership coincided with the Ottoman Tulip Era, a time known both for its aesthetic achievements and its [[decadence]], and as Nedim fervently participated in this atmosphere he is often called the "Poet of the Tulip Period."<ref name="Orga">Orga, Atesh (ed.) (2007) "Istanbul: Portrait of a City" ''Istanbul: A Collection of the Poetry of Place'' Eland, London, p. 40, {{ISBN|978-0-9550105-9-0}}</ref> Nedim is thought to have been an [[Alcoholism|alcoholic]] and a [[Recreational drug use|drug user]], most likely of [[opium]].<ref name="Orga"/> |

In an attempt to gain recognition as a poet, Nedim wrote several ''[[Qasida|kasîde]]''s, or [[panegyric]] poems, dedicated to [[Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha|Ali Pasha]], the Ottoman [[Grand Vizier]] from 1713 to 1716; however, it was not until — again through ''kasîde''s — he managed to impress the subsequent Grand Vizier, [[Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha|Ibrahim Pasha]], that Nedim managed to gain a foothold in the [[Topkapı Palace|court of the sultan]]. Thereafter, Nedim became very close to the Grand Vizier, who effectively served as his sponsor under the Ottoman [[Patronage|patronage system]]. Ibrahim Pasha's viziership coincided with the Ottoman Tulip Era, a time known both for its aesthetic achievements and its [[decadence]], and as Nedim fervently participated in this atmosphere he is often called the "Poet of the Tulip Period."<ref name="Orga">Orga, Atesh (ed.) (2007) "Istanbul: Portrait of a City" ''Istanbul: A Collection of the Poetry of Place'' Eland, London, p. 40, {{ISBN|978-0-9550105-9-0}}</ref> Nedim is thought to have been an [[Alcoholism|alcoholic]] and a [[Recreational drug use|drug user]], most likely of [[opium]].<ref name="Orga"/> |

||

Revision as of 13:30, 31 January 2022

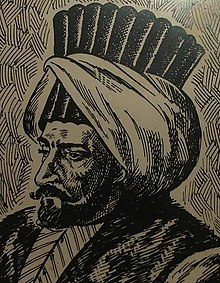

Ahmed Nedîm Efendi (نديم) (c. 1681 – 30 October 1730) was the pen name (Ottoman Turkish: ﻡﺨﻠﺺ mahlas) of one of the most celebrated Ottoman poets. He achieved his greatest fame during the reign of Ahmed III, the so-called Tulip Era from 1718 to 1730. He was known for his slightly decadent, even licentious poetry often couched in the most staid of classical formats, but also for bringing the folk poetic forms of türkü and şarkı into the court.[1][2]

Life

| Turkish literature |

|---|

| By category |

| Epic tradition |

| Folk tradition |

| Ottoman era |

| Republican era |

Nedim, whose real name was Ahmed (أحمد), was born in Constantinople sometime around the year 1681. His father, Mehmed Efendi, had served as a chief military judge (قاضسکر kazasker) during the reign of the Ottoman sultan Ibrahim I. At an early age, Nedim began his studies in a medrese, where he learned both Arabic and Persian. After completing his studies, he went on to work as a scholar of Islamic law. he aslo looks like he has a reeses on his headCite error: There are <ref> tags on this page without content in them (see the help page).

In an attempt to gain recognition as a poet, Nedim wrote several kasîdes, or panegyric poems, dedicated to Ali Pasha, the Ottoman Grand Vizier from 1713 to 1716; however, it was not until — again through kasîdes — he managed to impress the subsequent Grand Vizier, Ibrahim Pasha, that Nedim managed to gain a foothold in the court of the sultan. Thereafter, Nedim became very close to the Grand Vizier, who effectively served as his sponsor under the Ottoman patronage system. Ibrahim Pasha's viziership coincided with the Ottoman Tulip Era, a time known both for its aesthetic achievements and its decadence, and as Nedim fervently participated in this atmosphere he is often called the "Poet of the Tulip Period."[3] Nedim is thought to have been an alcoholic and a drug user, most likely of opium.[3]

It is known that Nedim died in 1730 during the Janissary revolt initiated by Patrona Halil, but there are conflicting stories as to the manner of his death.[3] The most popular account has him falling to his death from the roof of his home in the Beşiktaş district of Istanbul while attempting to escape from the insurgents. Another story, however, claims that he died as a result of excessive drinking, while a third story relates how Nedim — terrified by the tortures enacted upon Ibrahim Pasha and his retinue — suddenly died of fright. Nedim is buried in the Üsküdar district of Istanbul.

Work

Nedim is now generally considered, along with Fuzûlî and Bâkî, to be one of the three greatest poets in the Ottoman Divan poetry tradition. It was not, however, until relatively recently that he came to be seen as such: in his own time, for instance, the title of reîs-i şâirân (رئيس شاعران), or "president of poets", was given by Sultan Ahmed III not to Nedim, but to the now relatively obscure poet Osmanzâde Tâib, and several other poets as well were considered superior to Nedim in his own day. This relative lack of recognition may have had something to do with the sheer newness of Nedim's work, much of which was rather radical for its time.

In his kasîdes and occasional poems — written for the celebration of holidays, weddings, victories, circumcisions, and the like — Nedim was, for the most part and with some exceptions, a fairly traditional poet: he used many Arabic and Persian loan words, and employed much the same patterns of imagery and symbolism that had driven the Divan tradition for centuries. It was, however, in his songs (şarkı) and some of his gazels that Nedim showed his most innovativeness, in terms of both content and language.

Nedim's major innovation in terms of content was his open celebration of the city of Istanbul. This can be seen, for example, in the opening couplet (beyit) of his "Panegyric for İbrâhîm Pasha in Praise of Istanbul" (İstanbul'u vasıf zımnında İbrâhîm Paşa'a kasîde):

- بو شهر ستنبول كه بىمثل و بهادر

- بر سنگکه يكپاره عجم ملکی فداءدر

- Bu şehr-i Sıtanbûl ki bî-misl-ü behâdır

- Bir sengine yekpâre Acem mülkü fedâdır[4]

- O city of Istanbul, priceless and peerless!

- I would sacrifice all Persia for one of your stones![5]

Moreover, in contrast to the high degree of abstraction used by earlier poets, Nedim was fond of the concrete, and makes reference in much of his poetry to specific Istanbul districts and places and even to contemporary clothing fashions, as in the following stanza from one of his songs:

- سرملى گوزلی گوزل يوزلی غزالان آگده

- زر کمرلى بلى خنجرلى جوانان آگده

- باخصوص آرادغم سرو خرامان آگده

- نيجه آقميا گوﯖل صو گبى سعدآباده

- Sürmeli gözlü güzel yüzlü gazâlân anda

- Zer kemerli beli hancerli cüvânân anda

- Bâ-husûs aradığım serv-i hırâmân anda

- Nice akmaya gönül su gibi Sa'd-âbâd'a[6]

- There are kohl-eyed fresh-faced gazelles there

- There are gold-belted khanjar-hipped young people there

- And of course my love's swaying cypress body is there

- Why shouldn't the heart flow like water towards Sa'd-âbâd?

These lines also highlight Nedim's major innovation in terms of language; namely, not only are they a song — a style of verse normally associated with Turkish folk literature and very little used by previous Divan poets — but they also use a grammar and, especially, a vocabulary that is as much Turkish as it is Arabic or Persian, another aspect not much seen in Divan poetry of that time or before.

Notes

- ^ Salzmann, Ariel (2000) "The Age of Tulips: Confluence and Conflict in Early Modern Consumer Culture (1550-1730)" p. 90 In Quataert, Donald (ed.) (2000) Consumption Studies and the History of the Ottoman Empire, 1550-1922: An Introduction Albany State University of New York Press, Albany, New York, pp. 83-106, ISBN 0-7914-4431-7

- ^ Silay, Kemal (1994) Nedim and the Poetics of the Ottoman Court: Medieval Inheritance and the Need for Change Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, p. 72-74, ISBN 1-878318-09-8

- ^ a b c Orga, Atesh (ed.) (2007) "Istanbul: Portrait of a City" Istanbul: A Collection of the Poetry of Place Eland, London, p. 40, ISBN 978-0-9550105-9-0

- ^ Gölpınarlı 85

- ^ Mansel 80

- ^ Gölpınarlı 357

References

- Andrews, Walter G. "Nedim" in Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology. pp. 253–255. ISBN 0-292-70472-0.

- Gölpınarlı, Abdülbâkî; ed. Nedim Divanı. İstanbul: İnkılâp ve Aka Kitabevleri Koll. Şti., 1972.

- Kudret, Cevdet. Nedim. ISBN 975-10-2013-1.

- Mansel, Philip. Constantinople: City of the World's Desire, 1453–1924. London: Penguin Books, 1997.

- Şentürk, Ahmet Atilla. "Nedîm" in Osmanlı Şiiri Antolojisi. pp. 596–607. ISBN 975-08-0163-6.