Sentō: Difference between revisions

m Date/fix maintenance tags |

m →Tension between social groups: soldiers -> sailors |

||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

Foreigners are also usually easy to distinguish from Japanese in a ''sentō'' environment. However, except for a single case in a small town in Hokkaidō, described below, racial discrimination at public baths is virtually unheard of. As mentioned above, the Japanese public bath is one area where the uninitiated can seriously offend the regular customers by not following the rules, in particular by polluting the water in the bathtub. This often causes increased nervousness among the attendants upon seeing an unknown non-Japanese customer. ''Sentō'' commonly display a poster describing bathing etiquette and procedures in Japanese, and occasionally in English as well for international customers. |

Foreigners are also usually easy to distinguish from Japanese in a ''sentō'' environment. However, except for a single case in a small town in Hokkaidō, described below, racial discrimination at public baths is virtually unheard of. As mentioned above, the Japanese public bath is one area where the uninitiated can seriously offend the regular customers by not following the rules, in particular by polluting the water in the bathtub. This often causes increased nervousness among the attendants upon seeing an unknown non-Japanese customer. ''Sentō'' commonly display a poster describing bathing etiquette and procedures in Japanese, and occasionally in English as well for international customers. |

||

[[Image:Japanese_only_sign.jpg|thumb|"Japanese only" sign at Yunohana ''Onsen'']]In some cases a bath house does not allow foreign customers at all. For example, some ports in [[Hokkaidō]] are frequently used by the [[Russia|Russian]] fishing fleet. Some ''sentō'' there claim to have regular problems with drunk Russian |

[[Image:Japanese_only_sign.jpg|thumb|"Japanese only" sign at Yunohana ''Onsen'']]In some cases a bath house does not allow foreign customers at all. For example, some ports in [[Hokkaidō]] are frequently used by the [[Russia|Russian]] fishing fleet. Some ''sentō'' there claim to have regular problems with drunk Russian sailors misbehaving in the bath. One in particular, the Yunohana ''Onsen'', subsequently prohibited anyone who did not look racially Japanese from entering. This case gained a lot of publicity throughout Japan when three [[whites|Caucasian]] men, [[Arudou Debito]], [[Olaf Karthaus]] and Ken Sutherland, tried to use the baths. They were refused entry on three separate occasions, despite the fact that Arudou Debito is a [[Foreign-born Japanese|naturalised Japanese citizen]] and presented proof of such to the ''onsen''. As a result they brought a [[racial discrimination]] lawsuit against the ''sentō'' and the city of Otaru, Sapporo. The three men won the lawsuit and the ''sentō'' was ordered to pay 1,000,000 yen to each of them and to stop refusing entry to customers on the grounds that they do not look Japanese. On the other hand, it was also ruled that although the city of Otaru is as "duty-bound" as the national government of Japan to bring racial discrimination to an end,{{Fact|date=February 2007}} it "is under no clear and absolute obligation to prohibit or bring to an end concrete examples of racial discrimination by establishing local laws."{{Fact|date=February 2007}} (see also [[Ethnic issues in Japan]], [[Arudou Debito]]) |

||

While, for various personal beliefs, some Japanese may feel offended by sharing the same bathtub with a foreigner, such racist situations are very rare, and usually the offended party has no choice but to keep his/her anger to him/herself or leave the bath. |

While, for various personal beliefs, some Japanese may feel offended by sharing the same bathtub with a foreigner, such racist situations are very rare, and usually the offended party has no choice but to keep his/her anger to him/herself or leave the bath. |

||

Revision as of 22:35, 14 February 2007

Sentō (銭湯) is a type of Japanese communal bath house where customers pay for entrance. Traditionally these bath houses have been quite utilitarian, with one large room separating the sexes by a tall barrier, and on both sides, usually a minimum of lined up faucets and a single large bath for the already washed bathers to sit in among others. Since the second half of the 20th century, these communal bath houses have been decreasing in numbers as more and more Japanese residences now have bathrooms. Some Japanese find social importance in going to public baths, out of the theory that physical proximity/intimacy brings emotional intimacy, which is termed skinship in Japanese. Others go to a sentō because they live in a small housing facility without a private bath or to enjoy bathing in a spacious room and to relax in saunas or jet baths which often accompany new or renovated sentōs. Another type of Japanese public bath is onsen, which uses hot water from a natural hot spring. However, they are not exclusive: a sentō can be called an onsen if it derives its bath water from naturally heated hot springs. A legal definition exists which can classify a public bathing facility as sentō.

Sentō layout and architectural features

Entrance area

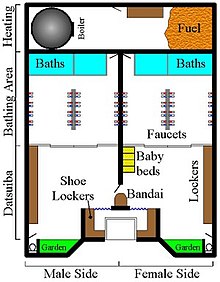

There are many different looks for a Japanese sentō, or public bath. Most traditional sentō, however, are very similar to the layout shown on the right. The entrance from the outside looks somewhat similar to a temple, with a Japanese curtain (暖簾, noren) across the entrance. The curtain is usually blue and shows the kanji 湯 (yu, lit. hot water) or the corresponding hiragana ゆ. After the entrance there is an area with shoe lockers, followed by two long curtains or door, one on each side. These lead to the datsuijo (脱衣場, changing room), also known as datsuiba for the men and women respectively. The men's and the women's side are very similar and differ only slightly.

Changing room

A public bathing facility in Japan typically has one of two kinds of entrances. One is the front desk variety, where a person in charge sits at a front desk, abbreviated as "front." The other entrance variety is the bandai style. In Tokyo, 660 sentō facilities have a "front"-type entrance, while only 315 still have the more traditional bandai-style entrance. [1]

Inside, between the entrances is the bandai (番台), where the attendant sits. The bandai is a rectangular or horseshoe-shaped platform with a railing, usually around 1.5 to 1.8 m high. Above the bandai is usually a large clock. Immediately in front of the bandai is usually a utility door, to be used by the attendants only. The dressing room is approximately 10 m by 10 m square, covered with tatami mats and contains the lockers for the clothes. Often, there is also a large shelf storing the equipment for regular customers.

The ceiling is very high, at 3 to 4 m. The separating wall between the men's and the women's side is about 2 m high. The dressing room also often has access to a very small Japanese garden with a pond, and a Japanese-style toilet. There are a number of tables and chairs, including some coin-operated massage chairs. Often there is also a freezer with ice cream and a drink vending machine. Usually there is also a scale to measure the body weight, and sometimes the height. In some very old sentō, this scale may use the traditional Japanese measure monme (匁, 1 monme = 3.75 g) and kan (1 kan = 1000 monme = 3.75 kg). Similarly, in old sentō the height scale may go only to 180 cm. Local business often advertises in the sentō. The women's side usually has some baby beds, and may have more mirrors. The decoration and the advertising is often gender-specific on the different sides.

Bathing area

The bathing area is separated from the changing area by a sliding door to keep the heat in the bath. An exception are baths in the Okinawa region, as the weather there is usually already very hot, and there is no need to keep the hot air in the bath. Therefore sentō in Okinawa usually have no separation between the changing room and the bathing area, or only a small wall with an opening to pass through. The bathing area is usually tiled. Near the entrance area is a supply of small stools and buckets. There are a number of washing stations at the wall and sometimes in the middle of the room, each with usually two faucets (karan, カラン, after the Dutch word kraan for faucet), one for hot water and one for cold water, and a shower head. At the end of the room are the bathtubs, usually at least two or three with different water temperatures, and maybe also an electric bath. In the Osaka and Kansai area the bathtubs are more often found in the center of the room, whereas in Tokyo they are usually at the end of the room. The separating wall between the men and the women side is also about 2 m high, whereas the ceiling may be 4 m high, with large windows in the top. On rare occasions the separating wall also has a small hole. This was used in old times to pass the soap between family members, but nowadays most people can afford a soap per family member. At the wall on the far end of the room is usually a large picture for decoration. Most often this is Mt. Fuji as seen in the picture to the right, but it may be a general Japanese landscape, a (faux) European landscape, a river or ocean scene. On rarer occasions it may also show a group of warriors or a female nude on the male side or playing children or a female beauty on the women side.

Boiler room

Behind the bathing area is the boiler room (釜場, kamaba), where the water is heated. This may use oil or electricity, or any other type of fuel such as, for example, wood chippings. After the war Tokyo often had power outages when all bath house owners turned on the electric water heating at the same time.

Sauna

Many sentō these days have a sauna with a bathtub of cold water just outside it for cooling off afterwards. It should be noted that you are expected to pay an extra fee to use the sauna, and you will often receive a simple wristband to signify your payment of the extra fee.

Sentō etiquette

This section describes the basic procedure to use a sentō. While the Japanese are usually very understanding if foreigners make cultural mistakes, the public bath is one area where the uninitiated can seriously offend the regular customers.

Equipment

Taking a bath at a public sentō requires at a bare minimum a small towel and some soap/shampoo. Both can also be purchased at the attendant. Often, many people bring two towels, a larger soft towel for drying and a smaller scrub towel (usually nylon) for washing. Other body hygiene products may include a pumice stone, toothbrush, toothpaste, shaving equipment, combs, shower caps, pomade, make up products, powder, creams, etc. Some customers also bring their own bucket. You may also bring some drinks, or a small toy for your children.

Entering and undressing

In Japan it is customary to remove one's shoes when entering a private home. Similarly shoes are removed before entering the bathing area in a sentō. They are kept in a shoe locker. The locker is usually available for free. Afterwards bathers go through one of the two doors depending on their gender. The men's door usually has a bluish color and the kanji for men (男, otoko), and the women's door usually has a reddish color and the kanji for woman (女, onna). In case of doubt, wait quietly for the next customer. After entering, you will find the attendant on the bandai (stand) between the two doors. The fee is paid here. The fee is set at 430 yen for all sento in Tokyo[1]. The attendant usually provides at extra cost a variety of bath products including towel, soap, shampoo, razor, and comb. Ice cream or juice from the freezer can also be paid for here.

After selecting an empty locker for your clothes and undressing, you should take the small towel, soap, shampoo, and perhaps more bathing products, and head to the bathing area.

Bathing area

After entering the bathing area, pick up a bucket and stool, and select a free set of faucets. You might want to quickly rinse the stool before sitting on it. Some customers also use the bucket to get some water out of the bathtub to quickly rinse their genitals. Carefully wash yourself at the faucet. Use the towel to scrub your back, and use soap and shampoo liberally. Try not to splash too much water on others. It is very important that everyone is very clean before entering the water, or else the water will be considered befouled and therefore unsuitable to soak in. When you are done showering, you should store your equipment in the bucket and head towards the bathtub.

Please, make sure you are quite clean and do not have any leftover soap or shampoo on yourself before entering the public bathtub. Keeping the water clean is the one fundamental rules for Japanese bathing. Getting soap in the bathtub will seriously offend all other customers, as will entering the bathtub without washing oneself. In this case, the owner of the bath house has to drain the bath, rinse it, and fill it again, losing time, money and customers. For the same reason you should keep your towel out of the water, although some Japanese ignore this rule.

While the importance of maintaining the cleanliness of the water is mutually understood, there are occasionally Japanese customers who enter the bathtub without washing themselves. This may be a case where the person has washed already at a recent previous bath, or it may be a case of bad etiquette. Also, like everywhere else, Japanese patrons are more likely to break the rules if nobody is looking, as for example the less frequented and smaller semi-public bath in a dormitory.

Now, you can pick the first tub to visit. There are various tubs with different temperatures and special features. For instance, you can choose an electric bath or a mineral bath. You can sit and relax as long as you like. As the baths are usually quite hot, this may not be very long. Sometimes the water is so hot that even experienced bathers can stand only three to five minutes in the water. Hot baths often have a ladle to stir the water. Remember that some people faint if they stay in the hot water for too long. If you want, cool down a bit with the colder water from the faucet, and reenter the bath, or climb out and stay in the cool air. (It will feel cold if you climb out of hot water.) You can stay in the sentō as long as you like.

At onsens, or hot springs, the water contains minerals, and many people do not rinse off the water from the skin, to increase exposure to the minerals. In a regular sentō you can rinse yourself off at the faucets. Afterwards dry yourself with the small towel while still in the bathing area. You should wring the towel out occasionally to keep it dry enough.

Getting dressed and leaving

In the changing room, you can purchase a drink or some ice cream, have a cigarette (if smoking is allowed), look at the garden, and get dressed. Commonly there are some coin-operated massage chairs as well. So, there is no rush to leave, and it's good to stretch out your money. Before leaving, women may want to put on makeup. After getting dressed, check that you didn't forget anything, go to put on your shoes, and leave.

Social and cultural aspects

Voyeurism and related problems

Whenever there are naked people, there is a risk of voyeurism. However, most customers at a public bath are regular customers, and anything out of the ordinary gets noticed immediately. Furthermore, the bath house owners do their utmost to prohibit voyeurism to protect their business, and consequently this sort of problem is rare.

Many bath houses have an attendant sitting on top of the bandai, with a good view of both the men's and the women's side. Most of the time the attendant is female, as few male customers have a problem with a female attendant while female customers may be embarrassed by having a male attendant able to see them.

True cases of voyeurism are rare. Reported cases usually have a male voyeur and a female victim. For example in 2001, there was a case involving a tall man who was able to see over the separating wall between the men's and women's sides. [citation needed] In another unusual case in 2003, a cross-dressing Japanese man entered the women's side of the bath. [citation needed]

In recent years there has also been an increased risk of voyeurs using video surveillance equipment. The risk is higher at a larger business or an open air bath.

Children may be allowed to join a parent of the opposite sex in the bath house, such as a little boy accompanying his mother into the women's bath. In Tokyo, the age limit for this is 10. Some adult customers are uncomfortable with this policy, fearing that children may take too much interest in the anatomy of members of the opposite sex.

Tension between social groups

Occasionally there are some tensions between different social groups in a sentō. Usually these apply only if a person can be assigned a social group despite being naked; i.e. having no clothes to demonstrate his status. The two main groups that are easy to distinguish from the mainstream Japanese are yakuza and foreigners.

In a sentō, yakuza (the Japanese mafia) are often easily distinguished by a full body tattoo beneath their clothes. Consequently, some public baths, especially in regions on a neighborhood watch program, have a sign that simply refuses entry for people with tattoos.

Foreigners are also usually easy to distinguish from Japanese in a sentō environment. However, except for a single case in a small town in Hokkaidō, described below, racial discrimination at public baths is virtually unheard of. As mentioned above, the Japanese public bath is one area where the uninitiated can seriously offend the regular customers by not following the rules, in particular by polluting the water in the bathtub. This often causes increased nervousness among the attendants upon seeing an unknown non-Japanese customer. Sentō commonly display a poster describing bathing etiquette and procedures in Japanese, and occasionally in English as well for international customers.

In some cases a bath house does not allow foreign customers at all. For example, some ports in Hokkaidō are frequently used by the Russian fishing fleet. Some sentō there claim to have regular problems with drunk Russian sailors misbehaving in the bath. One in particular, the Yunohana Onsen, subsequently prohibited anyone who did not look racially Japanese from entering. This case gained a lot of publicity throughout Japan when three Caucasian men, Arudou Debito, Olaf Karthaus and Ken Sutherland, tried to use the baths. They were refused entry on three separate occasions, despite the fact that Arudou Debito is a naturalised Japanese citizen and presented proof of such to the onsen. As a result they brought a racial discrimination lawsuit against the sentō and the city of Otaru, Sapporo. The three men won the lawsuit and the sentō was ordered to pay 1,000,000 yen to each of them and to stop refusing entry to customers on the grounds that they do not look Japanese. On the other hand, it was also ruled that although the city of Otaru is as "duty-bound" as the national government of Japan to bring racial discrimination to an end,[citation needed] it "is under no clear and absolute obligation to prohibit or bring to an end concrete examples of racial discrimination by establishing local laws."[citation needed] (see also Ethnic issues in Japan, Arudou Debito)

While, for various personal beliefs, some Japanese may feel offended by sharing the same bathtub with a foreigner, such racist situations are very rare, and usually the offended party has no choice but to keep his/her anger to him/herself or leave the bath.

Sanitary challenges

Japanese public baths have suffered infrequent outbreaks of dangerous legionella bacteria. In order to prevent such problems, the sentō union adds chlorine to its baths.

History of the sentō

The origins of the Japanese sentō and the Japanese bathing culture in general can be traced to the Buddhist temples in India, from where it spread to China, and finally to Japan during the Nara period (710 to 784).

Religious bathing from the Nara period to Kamakura period

Initially, due to its religious background, baths in Japan were usually found in a temple. These baths were called yūya (湯屋, lit. hot water shop), or later when they increased in size ōyuya (大湯屋, lit. big hot water shop). These baths were most often steam baths (蒸し風呂, mushiburo, lit. steam bath). While initially these baths were only used by priests, sick people gradually also gained access, until in the Kamakura period (1185 to 1333) sick people were routinely allowed access to the bath house. Wealthy merchants and members of the upper class soon also included baths in their residences.

The start of the commercial baths during the Kamakura period

The first mentioning of a commercial bath house is in 1266 in the Nichiren Goshoroku (日蓮御書録). These mixed-sex bath houses were only vaguely similar to modern bath houses. After entering the bath, there was a changing room called datsuijo (脱衣場). There the customer also received his/her ration of hot water, since there were no faucets in the actual bath. The entrance to the steam bath was only a very small opening with a height of about 80 cm, so that the heat did not escape. Due to the small opening, the lack of windows, and the thick steam, these baths were usually very dark, and customers often cleared their throats to signal their position to others. It can safely be assumed that on occasions an amorous couple used the dark room for more than mere bathing, and also amorous singles may have less-than-accidentally bumped into members of the other sex. Nevertheless, or maybe even especially because the very casual atmosphere, the bath was considered a great place to just hang out and chat. Most baths also had a salon on the second floor for resting.

Bathing in the Edo period

At the beginning of the Edo period (1603 to 1867), there were two types of baths common in different regions. In Tokyo (then called Edo), the normal bath was a regular bath with a pool called yuya (湯屋, lit. hot water shop), whereas in Osaka a bath was a steam bath with only a shallow pool and was called mushiburo (蒸し風呂, lit. steam bath), or just furo (風呂).

At the end of the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate (1603 to 1868) at different times required baths to segregate by sex to preserve public morals. However, many bath house owners simply added a small board to separate the bath, with little effect for the preservation of morals. Other baths had men and women bathe at different times or different days, and some baths limited themselves entirely to female or male clientele. The laws about mixed-sex bathing were soon relaxed again.

One reason for the popularity of the baths were the female bathing attendants yuna (湯女, lit. hot water woman). These attendants helped the customers by scrubbing their backs. However, after the bath officially closed, many of these women sold sex to male customers[citation needed]. Even nowadays, some brothels in Japan specialize on having young women clean their male customers in a private bath. These establishments are called sōpu rando (ソープランド, soapland). Subsequently, the Tokugawa shogunate limited the number of Yuna to three per bath house, to preserve the public morals. However, this rule was widely ignored, and shortly thereafter in 1841 the Tokugawa shogunate prohibited any Yuna to serve in a bath house, and furthermore prohibited mixed-sex bathing again. Large numbers of unemployed Yuna thereafter moved to the official red-light districts to continue their services. Up to 1870 there were also male washing assistants called sansuke (三助, lit. three helps) for washing and massaging both male and female customers. These male workers, however, usually did not participate in prostitution. The prohibition of mixed-sex bathing again did not last long, and when Commodore Perry visited Japan in 1853 and 1854, he was displeased about the lack of morals due to mixed sex bathing. Subsequently, the Tokugawa shogunate prohibited mixed sex bathing again.

The beginning of the modern bath house in the Meiji period

During the Meiji period (1867-1912) the design of Japanese baths changed considerably. The narrow entrance to the bathing area was widened considerably to a regular-sized sliding door, the bathtubs were sunk partially in the floor so that they can be entered easier, and the height of the ceiling of the bath house was nothing less than doubled. Since the bath now focused on hot water instead of steam, windows could be added, and the bathing area became much brighter. The only difference of these baths to the modern bath was the use of wood for the bathing area and the lack of faucets.

Furthermore, another law for segregated bathing was passed in 1890, allowing only children below the age of 8 to join a parent of the opposite sex.

Rebuilding the baths after the great Kantō earthquake

At the beginning of the Taisho period (1912 to 1926), tiles gradually replaced wooden floors and walls in new bath houses. On September 1, 1923 the great Kantō earthquake devastated Tokyo. The earthquake and the subsequent fire destroyed most baths in the Tokyo area. This accelerated the change from wooden baths to tiled baths, as almost all new bath houses were now built in the new style using tiled bathing areas. At the end of the Taisho period, faucets also became more common, and this type of faucet can still be seen today. These faucets were called karan (カラン, after the Dutch word kraan for faucet). There were two faucets, one for hot water and one for cold water, and the customer mixed the water in his bucket according to his personal taste.

Rebuilding the baths again after World War II: the golden era of the sentō

During World War II (for Japan 1941 to 1945), many Japanese cities were razed by firebombing, and Hiroshima and Nagasaki were attacked with atomic weapons. Subsequently, most bath houses were destroyed along with the cities. The lack of baths caused the reappearance of communal bathing, and temporary baths were constructed with the available material, often lacking a roof. Furthermore, as most houses were damaged or destroyed, few people had access to a private bath, resulting in a great increase in customers for the bath houses. New buildings in the post war period also often lacked baths or showers, leading to a strong increase in the number of public baths. In 1965 many baths also added showerheads to the faucets in the baths. The number of public baths in Japan peaked around 1970.

The decline of the sentō in the modern times

Immediately after World War II, resources were scarce and few homeowners had access to a private bath. Private baths began to be more common around 1970, and most new buildings included a bath and shower unit for every apartment. Easy access to private baths led to a decline in customers for public bath houses, and subsequently the number of bath houses is decreasing. Many Japanese young people today are embarrassed to be seen naked, and avoid public baths for this reason. Some Japanese are concerned that without the "skinship" of mutual nakedness, children will not be properly socialized.

The future of the sentō

While the traditional sentō is in decline, many bath house operators have adjusted to the new taste of the public and are offering a wide variety of services. Some bath houses emphasize their tradition, and run traditionally-designed bath houses to appeal to clientele seeking the lost Japan. These bath houses are also often located at scenic spots in nature and may include an open-air bath. Some also try drilling in order to gain access to a hot spring, turning a regular bath house into a more prestigious onsen.

Other bath houses with less pristine buildings or settings change into so called super sentō and try to offer a wider variety of services beyond the standard two or three bathtubs. They may include a variety of saunas, reintroduce steam baths, include jacuzzis, and may even have a water slide. They may also offer services beyond mere cleansing, and turn into a spa, offering medical baths, massages, fango baths, fitness centers, etc., as for example the Spa LaQua at the Tokyo Dome City entertainment complex. There are also entire bath house theme parks, including restaurants, karaoke, and other entertainment, as for example the ōedo onsen monogatari (大江戸温泉物語, Big Edo Hot Spring Story) in Odaiba, Tokyo. (Note: The Ōedo Onsen Monogatari is not a sentō.) Some of these modern facilities may require the use of swimsuits and are more similar with a western style water amusement park than a sentō.

See also

- Jjimjilbang

- Onsen (hot spring bath houses)

- Hot spring

- Mikvah - a communal ritual bath used in the present day by devout Jews for mostly religious ceremonies. Traditionally, the mikvah was used by both men and women for various purposes; its main use nowadays is by Jewish women to achieve ritual purity after menstruation or childbirth.